There are 26 bones in the human foot (28 if you include the sesamoid bones at the base of the big toe).

The Basic Book of Human Anatomy

Growing up in rural southern Illinois in the 1950s, and going barefoot wherever possible, my brother, Marshall, and I were probably more attuned to the existence of our feet than many of our city counterparts. Unfortunately, winter’s long bitter cold kept the ground a pulsing block of ice even as the air temperatures often rose to spring-like settings in late February. It would be deep into March before the two of us could go comfortably outside without shoes.

It was our bare feet that always told us when true spring had arrived, the first occasion that I remember this occurring being in the spring of 1955, when I was going on four years of age and Marshall five. We were finally old enough to venture from our farmhouse, and made mad by spring fever, we frantically pursued our Dad as he pulled a disk with our little Ford tractor back and forth across the field that sat to the west of our house, the clattering disk breaking up the freshly plowed ground and preparing it for spring planting.

As we sprinted and shouted after Dad on the tractor, the clods of moist earth squished like warm little biscuits beneath our bare feet and the heady smell of newly turned dirt seemed all the world like the earth rejoicing.

Once free of our shoes, we soon became little Huck Finns, gaining brown, horny calluses on the bottoms of our feet, making them all but impervious to most any surface, except for the sharp gravel rocks in our driveway and the woody stubble of harvested hay fields. So confident were we then in the toughness of our feet that we almost never, unless going to church or town, wore shoes that summer—a terrible mistake, as we were to discover.

One day in late August, Marshall and I were summertime shoeless, playing outside at Mabel Knauss’s, a neighbor two decades older that our mother who looked after us occasionally so our mom could have a break from our constant getting into things. Hard outside work in the sun had already chiseled deep wrinkles in Mabel’s face, giving her a no-nonsense gaze, but in truth, she liked rascally little boys. She made over us, preparing our favorite foods and giving us anything we asked for that we found when pilfering through the house, including long strings of firecrackers her now grown sons had long forgotten. While we played outside, she spent much of her time on the phone—a massive, old-fashioned, crank-type contraption that could have killed a kid if it had fallen off the wall, an instrument of endless community gossip in the somewhat remote area in which we lived.

On that late summer day at Mabel’s, as we played with our battered little toy trucks in the brown sun-scorched grass at the far edge of the yard, Marshall suddenly nudged me, pointing with his chin in the direction from which our dad, and not our mother, came speeding up the narrow graveled lane in our family’s dust-covered blue Ford. The vehicle fishtailed like a race car the last few yards, bits of gravel scattering in the car’s wake.

The car rolled to a stop and was instantly enveloped in a cloud of chalky dust. Before the dust settled, our thick-shouldered father climbed out, throwing a wet-tipped cigar to the ground. Mabel came out of the house, her arms folded tightly across her chest, as if to comfort herself. It was at that moment I remembered how Mabel’s conversations on the phone that afternoon had turned quiet on her end, an odd occurrence given her outgoing personality. To add to the mystery, no words were spoken between the adults as our dad ordered us to get into the car, Marshall in the front seat and me in the back. The puzzling atmosphere only deepened when our dad, gripping high up on the steering wheel with beefy hands, failed to turn left, toward home, when we came to the main road.

The drive, continuing in odd and worrisome silence, led to countryside with which I was unfamiliar, though the landscape stayed rural if not more uninhabited looking. Later, I learned we were somewhere near the small village of Kell, Illinois.

It was Marshall, with a surprised yelp, who pointed out an ugly, twisting shaft of black smoke curling up in the distance, an oily-looking column that was an obscene smear on an otherwise perfectly deep blue sky—a vision that promised only trouble.

A few more minutes of driving brought us to where numerous cars and pickup trucks sat parked haphazardly on both sides of the narrow country road. Some were barely out of the way, as if some unplanned county fair in the middle of nowhere had suddenly been announced on the Mount Vernon radio station and people had rushed to get there.

We got out of the car, crossed a dry shallow ditch full of late summer weeds and began walking into a field. There had been a grass fire over several acres, and a few spots were still burning, hot points of coals that might easily do great damage to my brother’s and my bare feet.

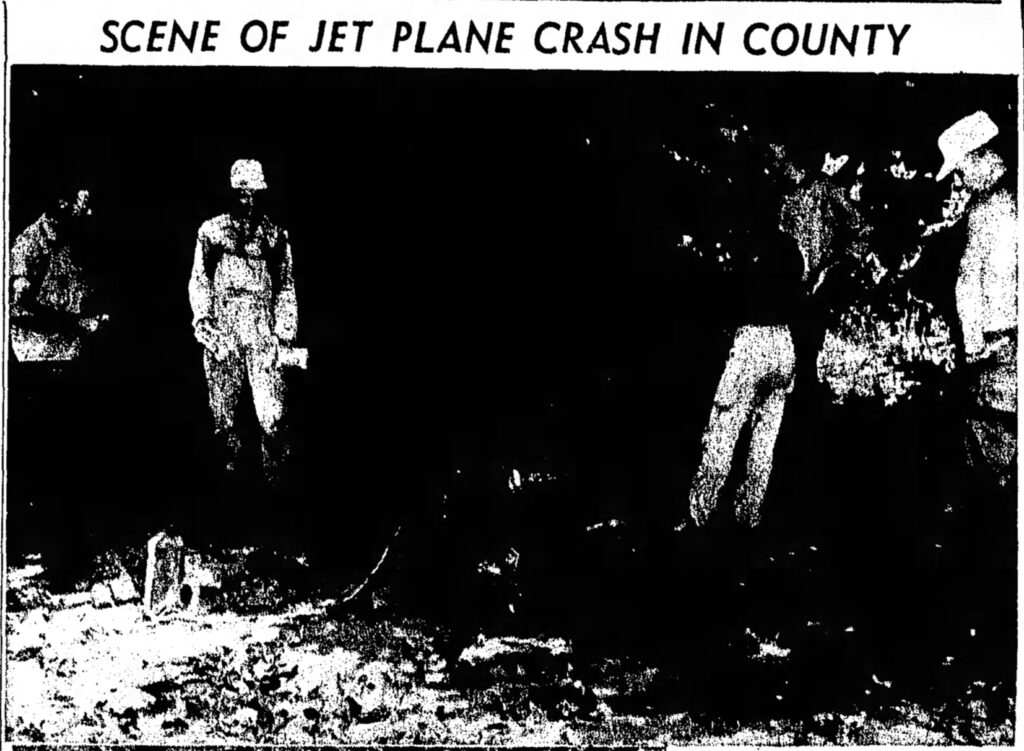

Marshall and I halted just inside the edge of the field, bringing our Dad to an abrupt stop. We had but an instant to take it all in—people everywhere, walking alone or in small groups, rubbing eyes made watery by smoke, many keeping their eyes glued to the ground like an Easter egg hunt, thin nasty little swirls of brownish smoke drifting up around the moving figures from spots of still smoldering earth.

“Move,” Dad commanded.

Dad’s hurried steps toward some unseen center took us through still burning spots of grass, stubble, and earth. Shoeless, Marshall and I hopped and leaped around like novice converts at a primitive ritual, trying to find the least painful way across hot coals. The thick, pointed stubble of the recently mowed field was another obstacle, cutting, puncturing, and tearing into the bottoms of our feet.

When we hesitated, Dad grabbed our hands and pulled us forward. I tried to yank from my father’s sweaty grasp, even letting go of a few low growls of frustration. His grip just grew tighter. When my brother and I finally gave out, Dad half dragged us along, me on the left and my brother on the right, our dad swept along by a powerful invisible current.

We finally stopped at a long, blackened trench from which most of the smoke was rising. Next to this gouged-out furrow, two dozen or so men gathered in a large circle, talking quietly. Save for my brother and me, there were no other kids.

Inside the circle three men knelt, picking through and inspecting items lying on a wrinkled piece of canvas. Their faces were smudged with dirt and smoke made grimier by sweat.

I stayed behind my dad’s legs, grasping his loose pants, standing away from the edge of the wrinkled tarp. Marshall broke away and moved in closer, while Dad spoke to an older man dressed in a dark suit who, amazingly enough, was not sweating, the loose skin on his face so pale it looked almost transparent. The man replied to my father’s question about what had happened. “A small jet. probably out of Scott Air Force Base. At least two on board, maybe more.”

Then the man swept his hand toward the tarp and added, “Hard to tell.”

Working up the courage to peek around my father’s leg, I finally took a closer look. Perhaps a dozen irregularly shaped chunks of something raw looking, gray and red, much of it mixed with bits of cloth lay scattered on the tarp. There were also twisted pieces of bright metal, none bigger than a baseball mitt, along with a single laced-up black boot. The boot stood upright at the center of the morbid collection, the three subdued men moving with an odd reverence around it.

In my memory the boot was still smoldering, a splinter of bright bone sticking out at the top.

As we carefully trekked back to our car, Marshall pointed out a neighbor, an older man so frail his sons had to boost him up on a tractor when there was field work to be done. He was setting out little red flags to mark plane debris, his determined motions so suddenly fluid, he seemed to be dancing in the receding curls of smoke.

We came back into our house so teary-eyed, and walking so gingerly, that for once our mother’s anger out-dueled our father’s moodiness, Mabel Knauss no doubt using her dinosaur of a telephone to inform our mom about where Dad had taken us. Mother told my brother and me to sit at the edge of the sagging bed we shared, inspecting the condition of our poor feet, passing occasional looks of scorn at our dad while she patted our heads, cooing to us. She carefully cleaned the cuts and scrapes with peroxide and, like Mary in the Bible, gently rubbed warm ointment on our feet, albeit the antiseptic kind.

The National Transportation Safety Board did not exist in 1955, and the plane crash to which our father unexpectedly took my brother and me straddled a very rural county line, adding further to the remoteness of the site and raising confusing questions about what authorities were in charge. I won’t say they were not present, but I do not remember any police or military vehicles or officials there, just the county coroner, who spoke briefly to our dad that day, and hundreds of local curious neighbors and strangers who quietly foraged through the still smoldering grass and earth, as if it was a community event, a quiet carnival without booths or rides but with plenty of prizes.

The next time we went to stay with Mabel, she read aloud a piece from the Kell News section about the crash in the Mt. Vernon Register News. Marshall got up before Mabel finished reading, antsy, wanting me to follow him outside, but I sat there, mesmerized.

Our neighborhood is still shocked by the jet plane crash in our vicinity. It was the worst thing most of us have seen, except our soldier sons that were in combat. The plane crashed nearly a half mile from my home and my house shook as though it had hit our roof. There was a terrific noise, and three distinct explosions. There wasn’t much fire by the time we arrived on the scene, but there appeared to have been a flash fire as all the weeds in the vicinity were burned. The bodies were found quite a distance from the plane. The front of the plane fell behind the barn on Nelson Litteral’s farm and the rest of the plane was scattered across two ten-acre fields. The still smoldering bodies were soon identified by the pilots’ license in their billfolds. It is estimated that approximately three or four thousand people came to see the wreckage. They came early and were still arriving after dark.

When Mabel had finished reading, I asked if I could have the article to keep. She tore the piece out of the newspaper with a careful rip and handed it to me, saying, “You might want to put this somewhere where your mother doesn’t see it.”

Although it would be a few more years before I would be able to read the torn out article, it always seemed, whenever I’d take it out from its hiding place, a hundred times more potent than the many strings of firecrackers Mabel had let us take.

For years after the 1955 plane wreck, one could walk into a number of houses in our rural area and see an odd piece of twisted metal, usually aluminum, or heavy cable wires, maybe even a strange-looking gauge of some sort, displayed on a table or on a shelf, often in a front room. Mabel Knauss’s husband, Chester, a leathery-faced three-pack-a-day Camel man, whose rasping voice gave a strong hint of what his lungs must have looked like, was able to claim an altimeter about the size of a grown man’s fist that day, a beautiful thing, really, shined up and kept on display in the Knauss living room.

Although these trophies from the crash site may have made interesting conversation pieces for my rural neighbors, my visit to that smoldering field that day gave me a recurring nightmare for many years—of a small plane spiraling down to earth in the field next to our house, my family and I racing, losing our breaths, trying with all our might to get to the crash and see if anyone was still alive inside the horribly twisted wreckage. Thankfully, I never saw the fire-damaged boot from the day of the crash displayed in any of my neighbors’ houses, though I spent many a night over the coming years, after having one of those airplane nightmares, lying in bed and imagining how the boot’s owner might have somehow survived the crash, parachuting down to earth minus a foot but still destined to live out a reasonably normal life, grateful, so very grateful for that second chance.