The outlaw is perhaps the most distinctive of American folk types and, oddly enough, seems of more interest to the American reader than that of the hero.[i] Yet, it is still interesting when a hero of slight stature and unassuming qualities takes down a villainous outlaw, as in the story of Jasper, Indiana’s, diminutive tailor, J. P. Huther, at the turn of the 20th century. Like all good stories, it is a tale of unexpected and converging events.

Although Indiana is rarely thought of when American outlaw gangs of the 19th century are mentioned, the state was the home to three such gangs in the post-Civil War era—the Reno, Archer, and Reeves gangs.[ii] Perhaps the eventual neglect of these outlaw elements in Indiana, a sort of purposeful amnesia, came from the wish of many Indiana communities to quickly move on from embarrassing episodes of violence and lawlessness. By the beginning of the 20th century, one such Hoosier community that surely wished to be shed of any of its outlaw reputation was the quiet and prosperous town of Jasper, Indiana, the county seat of Dubois County.

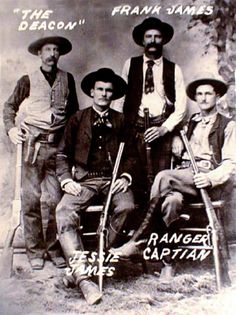

In the mid-1880s, the Reeves gang, led by two brothers, operated in the Dubois County area with impunity. When they finally came to their demise, newspapers styled them “the last of the Jesse James type robbers.”[iii] At the gang’s prime in 1885, George Reeves, at thirty-five, was the oldest of the brothers and stood almost six feet tall. John Reeves was a bit shorter and five years younger. Both men were well built, had dark hair and complexions, and wore long dark mustaches.[iv] The latter feature gave them a distinct bandito look. Earlier, in the mid-1870s, the brothers had “shot four men who were attempting to arrest them in Orange County” and escaped, this at the time their father was running a counterfeit racket there. The Reeves brothers were also known and respected for their quick use of and accurate aim with pistols. When in action, John was the brains and George the muscle. They were not men to be messed with.[v]

Another element in the story of the Reeves’ outlaw activities concerned the cultural dynamics of the region where they operated. The central and southern parts of Dubois County had gained a large and growing population of German Americans, equaling twenty-five percent of the population of the county by the time of the Civil War.[vi] This population was, by and large, a quiet, hardworking, and prosperous group, unfamiliar with large scale criminal activity. The Reeves, on the other hand, lived in Columbia Township in the northeast portion of Dubois County, an area populated by rough upland south settlers and their descendants. One Indianapolis newspaper described the region as “in as desolate and lonely spot as can be found in this section of the United States. The country is wild and broken, and abounds in hills, valleys, and rocky fastnesses, with numerous caves in the neighborhood to aid the evil-doers to hide from the light of day.”[vii]

The Reeves brothers must have had some commanding presence about them, as they were able to quickly assemble at least six gang members from the Columbia Township area to help steal and move horses. “They were all married men,” one newspaper later reported, “and most of them raised in the neighborhood, but were willingly led to rascality by such tutors as the Reeves.”[viii] The ruthless band grew bolder as time passed and, in the words of the Indianapolis Journal, became “a gang of cut-throats and robbers who had their way so long a time that they do not recognize the majesty of the law, nor the power of criminal courts.”[ix]

Dubois County law enforcement centered in Jasper suffered many humiliations trying to arrest the Reeves brothers, hampered as they were by the complex web of kinship loyalties in Columbia Township and from a lack of knowing the lay of the hilly rugged countryside. One newspaper reported in 1879 how two Dubois County deputies sent into Columbia Township on “a lively chase for some fugitives” were chased away by an angry woman “for shooting at her boy.”[x]

The most embarrassing episode for an officer of the law, however, occurred in 1883. That year, George and John Reeves had been arrested for robbing a store in Martin County. They had posted bail but never showed up at court. A warrant was issued for their arrest, but law officers feared the gang’s impulsive violent behavior. Dubois County sheriff Joseph Hoffman, who knew the family, confronted John Reeves in a garden patch by the Reeves home but made the mistake of going there alone. Reeves drew a gun on the sheriff and hollered, “Hoffman, god damn you, get out of here.”[xi] Hoffman quickly mounted his horse and retreated to Jasper.

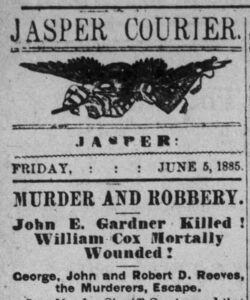

In 1885, a new sheriff, George Cox, set about finishing the job of arresting the Reeves brothers. His efforts, however,culminated in the murders of two Dubois County deputy sheriffs just outside Jasper in 1885, one of the dead being Sheriff Cox’s son. Many state and national newspapers carried the story of the buildup to the gun fight and the gruesome details of the murders. Just after the arrest of the Reeves brothers by the two Dubois County deputies, John Gardner and William Cox, One of the Reeves’ somehow took a pistol away from Gardner and immediately opened fire, shooting deputy Gardner in the head, then turning the gun on deputy Cox. The deputies were now disarmed and wounded, having not fired a shot. At this point, George Reeves picked up Cox’s revolver and walked over to where the bleeding Gardner lay, begging to be allowed to live a few hours longer. George, the most volatile of the brothers, laughed and told Gardner, “Dead men tell no tales.” He placed the barrel of the gun between the deputy’s eyes and pulled the trigger.

George then turned and shot Cox in the lower back, severing his spine.[xii] Gardner died a few hours later, while Cox lingered for two years before dying of complications of his wounding.

After the murders, the people of Dubois county were ready to run the gang to the ground, a newspaper reporting, “It probably won’t be very long until lynching by the wholesale will be indulged in.”[xiii] But justice was not to be. The Reeves brothers successfully escaped to Kentucky where they changed their names and their mode of criminal operations.

Once out of Indiana, the Reeves brothers, along with their new gang, continued their reign of outlaw terror in Kentucky and Tennessee for the next two years, this time blowing up safes in vulnerable small-town stores until they finally set fire to downtown Tompkinsville, Kentucky, in one of their robbery attempts in 1887. They were captured shortly afterwards, but remained as haughty as ever, George Reeves brazenly entertaining his guards by demonstrating his amazing skill “in freeing himself from the grasp of any set of handcuffs.”[xiv]

Despite the two gruesome killings in Dubois County in 1885, authorities in Jasper discovered they would have wait to try the Reeves for the Indiana murders, as the Reeves brothers were given long prison terms in the Kentucky penitentiary for their crimes of robbery and arson in that state. But there was yet another dramatic twist. In 1896, George and John Reeves escaped from the Kentucky penitentiary, and then seemingly disappeared from the face of the earth. After several years passed, it was assumed the brothers had died, probably at the hands of some of their unsavory friends.

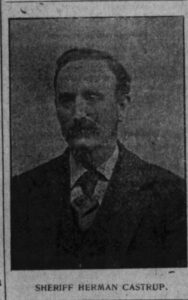

Sixteen years later, in 1901, the town of Jasper had all but forgotten about the Reeves gang, the city standing as a hub of prosperity in that region of the state. Most of the city’s shop owners and over half its population were of German ancestry.[xv] It was certainly a quieter place than it had been in post-Civil War days, with the county sheriff, forty-three-year-old Herman Castrup, a good-sized and well-respected law enforcement official who employed a practical no-nonsense approach when it came to anyone disturbing the peace, tamping down the few frontier-like impulses that still lingered up in the northern parts of the county.[xvi]

An issue of The Herald, one of two newspapers in the city of just under 2,000 people, noted the variety of commercial and social activities in its local activity section, including several advertisements by the town’s diminutive tailor, J. P. Huther, who went by the name of Pete. Huther’s well-kept shop sat on the east side of the public square and offered “suits made to order from $10 up, and pants from $ 3 up.”[xvii] Like many of Jasper’s citizens, he was born of German immigrants, his family coming to Ferdinand, Indiana, in 1878, when Pete was seven.

Huther moved to nearby Jasper in 1892, opening a clothing business, and continuing his tailoring work. In one of his earliest ads in the Jasper Weekly Courier, he told customers not to send away for suits, explaining, “I will make them for you as cheap as you can have them made to order in the cities, and the money you pay will be circulated at home.” He signed the ad, John P. Huther, The Tailor and Draper.[xviii]

One of the most distinctive qualities of Huther was his physical stature. He was only five foot six inches tall and weighed less than one hundred and thirty pounds.[xix] Although a quiet young man, Huther quickly rose in social and political status, being elected as the town clerk, and, in 1900, as the town treasurer. Sheriff Castrup, built tall and burly like one would expect of a county sheriff, often smiled when he passed the discreet little tailor whenever they crossed paths at the county courthouse.

Whatever their physical differences, however, both men played important roles in the Jasper and Dubois County community, and both men would soon be brought together in the most dramatic fashion in an event involving life or death, the latter coming in the form of the forgotten Reeves brothers.

After their escape from the Kentucky penitentiary in 1896, John and George Reeves escaped to southern Illinois where they started a new life as peddlers in the remote Horse Creek region of the state. The two men took the last name of Clark and hid in plain sight. They were completely close-mouthed when it came to explaining anything about their past, and it seemed a bit odd to some that the two entrepreneurial brothers would settle in the Horse Creek area in the first place. The Horse Creek community was considered a backward, exclusive, frontier-type region, spanning the southeastern portion of Marion County, all of Farrington Township in northeastern Jefferson County, and a small part of Hickory Hill Township to the southeast, in Wayne County. Trading with the clannish people would not be easy, but the Clark brothers apparently had charm or, more likely, came from a similar place and knew how to fit in, and their enterprise soon seemed to be thriving. Eventually, John would marry a nearby Centralia girl and move there, but George was more comfortable staying in the heart of the Horse Creek district.[xx]

Five years later, the Jefferson County sheriff began to grow suspicious of the Clark brothers, having heard rumors of their selling stolen goods. He began sending out inquiries throughout the region describing the two men. He was stunned after reading a reply from Kentucky authorities.

The story of the unexpected discovery and arrest of George and John Reeves in southern Illinois in early 1901 was carried in newspapers throughout the nation.[xxi] The Illinois authorities, led by Jefferson County Illinois sheriff Thomas Manion, had been warned by Kentucky official to take plenty of experienced law officers and not to take even the slightest of chances when going in for the arrest. It was well these directions were followed. For all their seemingly domesticated ways since changing their names and going into hiding, the Reeves brothers had several weapons hidden on them when law officers made the capture. A search of their homes further showed that they still dabbled in crime, in this case the practice of making and distributing counterfeit money.

John was taken first, but announced to the posse that his brother, George, “would kill them all” when they approached him. Sheriff Manion and his men, however, got the jump on George as well, the initial warning by the Kentucky people proving timely. When the story of the arrest came out, readers across the nation feasted on another outlaw tale. A St. Louis paper called the event of the two captures “dramatic” and “of the most thrilling nature, the most important arrest ever made in the county.”[xxii]

As the brothers traveled in handcuffs to the county jail in Mt. Vernon, John “upbraided his brother” for not stopping their arrest. George was heard swearing to his brother that he would do better next time, that he would either succeed or go down fighting.

The shocking news of the Reeves’ reappearance hit like a bombshell in Jasper. It was as if two very unwanted ghosts had somehow wandered back into the quiet town. The Herald, under the headline, Captured at Last, reported that county officials were unsure of what to do about the Illinois arrest. “The following dispatch from the Cincinnati Enquirer this morning will be of interest to our people. George and John Clarke, whose true name is said to be Reeves, were arrested yesterday in Jefferson County, Illinois, on the charge of having murdered Deputy Sheriff Gardner and Cox near Jasper, Indiana in 1885. . .. Dubois County never offered a reward for their capture and no effort has been made, as far as we could learn, to get them from Mt. Vernon, Illinois.”[xxiii] The Jasper Weekly Courier, aware of the pain and uproar that might come with bringing the Reeves boys back to Indiana for trial, noted its remedy to the problem. “If the people of Mt Vernon would lynch them it would do this community a commendable and gracious act.”[xxiv] The state of Kentucky, however, intervened for the time being, bringing the Reeves back to the bluegrass state and charging them with escaping from prison.

A month later, Dubois County officials finally got their act together, their actions driven after a telegraph message from a Kentucky official to Sheriff Castrup explaining that the Reeves brothers were going to be released from the Kentucky jail on habeas corpus proceedings. Upon receiving the message, Sheriff Castrup immediately went to the Indiana governor and got the state to start the process of bringing the Reeves brothers to Jasper to stand trial for the murders of the two deputies sixteen years before.[xxv]

Castrup rode the train to and from Kentucky to escort the brothers, the train slowly making its way to Huntingburg, Indiana, for the last leg of the trip by carriage to Jasper. A Jasper newspaper reporter went along on the train retrieval trip, writing, “All along the line the Reeves brothers were buoyant in spirits, and chattered with the sheriff and many acquaintances, until they reached Huntingburg, when they grew silent and seemed down-heart.” The brothers, who were now fifty and forty-five years of age were described as, “rather thin and have that hungry hunted look. They didn’t seem frightened when they left the train but were under a more or less nervous strain.”[xxvi]

A large crowd waited at the Huntingburg station, but the reporter was surprised that “there was no demonstration made upon the arrival of the train, as the crowd had gathered sorely out of curiosity and not one in fifty had ever seen the prisoners before.” Former Dubois County sheriff Joe Hoffman was the only one allowed to talk to the prisoners before the present sheriff started to Jasper with the two brothers. Hoffman, as noted, had been the county sheriff back when John Reeves had driven him away in humiliation over sixteen years before. This time, Hoffman got into John Reeves’ face and shouted, “Hello John Reeves; you won’t get a chance to pull a gun on me again.”[xxvii]

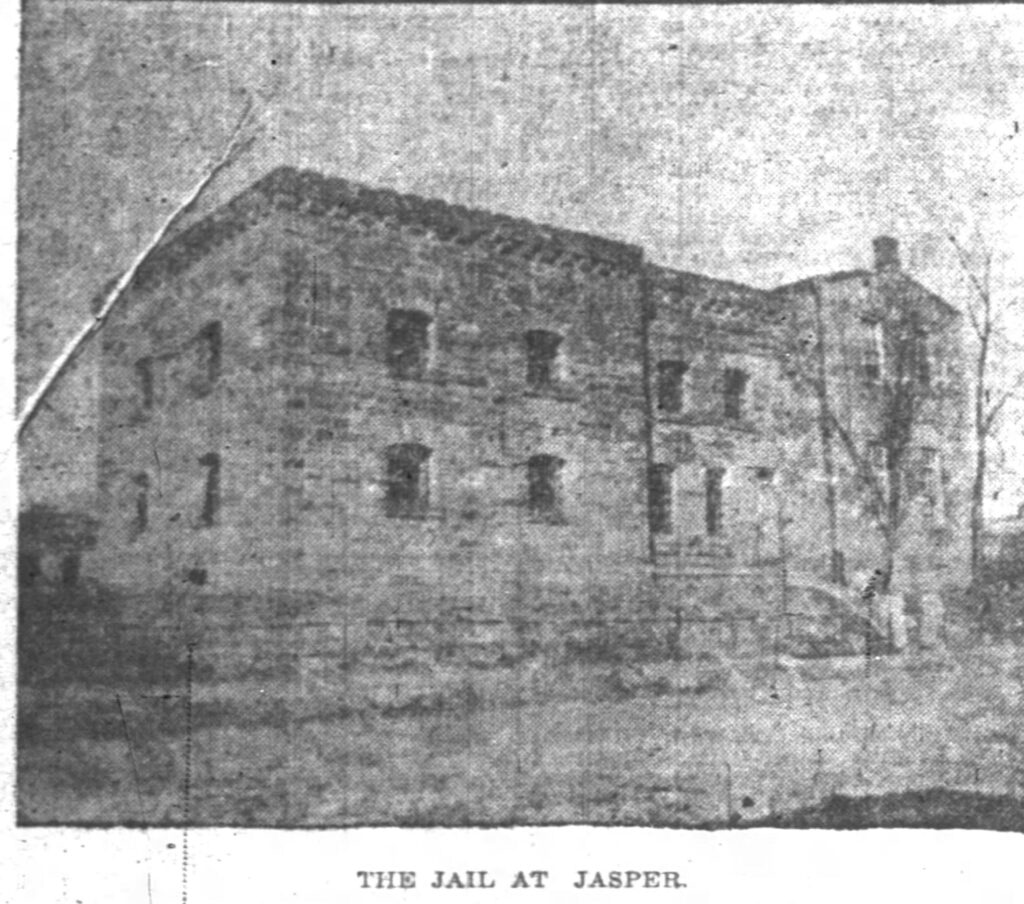

The captured brothers, both wearing a demeanor of resignation, were taken by buggy from Huntingburg, along with an escort of riders, the trip taking them up through the Patoka River Bottoms and on to the county seat at Jasper. Once in the Dubois County jail, however, it did not take the two former outlaws long to begin plotting an escape. The jail was in a rundown condition, and George Reeves talked a visitor who was at the jail seeing another inmate into bringing him several saws. The saw blades, however, proved to be too soft to be of any help. The blades were then hidden until they were discovered a few months later and the unsuccessful escape attempts made known.[xxviii]

Although he did not immediately find out about the saw blades, Sheriff Castrup did become suspicious that breakout attempts might be going on. This led to the Reeves brothers being sent to the state penitentiary in Jeffersonville while the Dubois County jail was refurbished with a new steel cell.

In hindsight, it could be debated whether Sheriff Castrup planned well enough for the escorting of the Reeves brothers back from the state penitentiary to Jasper. Part of the problem involved the short notice regarding the prisoners’ return. In early May of 1901, Castrup sent an order to Judge Ely for his signature to have the outlaws transferred from the state prison back to the Dubois county jail. Judge Ely, due to sickness, did not respond to the order, so a week later the sheriff made the same request.[xxix]

When Castrup finally received the paperwork he needed from the judge, it was too late to catch the afternoon train. Needing his deputy sheriff to stay and take care of any problems that might arise in the county, Castrup had little time to find someone else from the law enforcement system to go with him early the next morning.

Fate now played her hand. J. P. Huther, the diminutive Jasper tailor, happened by and Sheriff Castrup asked Huther to accompany him on the trip to bring back the Reeves brothers to Jasper. Perhaps Huther was in too good of a mood to possess sober judgement, having just been elected the city’s treasurer that week.[xxx] At any rate, the tailor said yes and was deputized.

The next morning, just after Castrup and Huther stepped on the train for Jeffersonville, the sheriff handed his new deputy a small revolver, explaining it was a five shot weapon and would likely not be needed. Once on the return trip, however, with the two prisoners in tow, Castrup may have thought differently. The Herald reported the next day that the two brothers “whispered consultations and acted suspiciously several times but were closely watched. It seemed they were planning to take desperate chances of escape.”[xxxi]

It did not help Huther’s confidence either that George Reeves grinned wickedly when he first saw the little deputy.

Huther felt relieved when the train finally pulled into the Huntingburg station at about nine o’clock that night. Waiting there was the regular deputy sheriff with a four-seat carriage to convey the lawmen and the prisoners back to Jasper. Given the darkness, there was talk of staying in Huntingburg until daylight, but the sheriff decided the three lawmen could easily handle the two handcuffed fugitives.

Accounts from the two Jasper newspapers gave ample information about what next transpired. George Reeves, the moodier of the two brothers, said not a word after the departure from the train but John Reeves announced that he was hungry and asked for a sandwich. George then said that he was hungry too and the brothers, in heavy handcuffs, were given food and began to eat quietly as the party moved to the stable.

Sheriff Castrup was meticulous with the seating arrangements in the carriage, tying together the arms of the two handcuffed prisoners together with thick leather straps, his powerful grip on the men as he tightened the straps letting them know he would stand for no foolishness. The sheriff placed George Reeves in the back right seat and sat himself down on the left with John on his lap. The deputy sheriff who drove the rig and little J. P. Huther took the two front seats.

With the sharp crack of a whip, the rig started north into the darkness at a fast clip for Jasper.

Sheriff Casrtrup remained on high alert. About two miles out of Huntingburg, he noticed George Reeves moving his hands about and ordered the buggy to be stopped, saying he wanted to light up a cigar. He used two matches, and in doing so saw the handcuffs were still securely locked on George Reeves’ wrists. He ordered the buggy to proceed.

The clip-clopping of the two horses in the darkness may have made the lawmen drowsy. If so, they became wide awake when George Reeves, a mile up the road from the first unexpected stop, abruptly asked for a match to light up his own cigar. The breeze, however, blew his match out. Huther, seeing a chance to check on George’s handcuffs again, turned around and gave Reeves his own cigar and bend over to light another for himself. In the flare of the match, he was able to see the handcuffs remained secure.

Fifty yards ahead, the buggy started moving into heavy timber, the branches of which overarched the road, making the night even darker there. At this point, the travelers were in the heart of the Patoka River valley, close to Briarfield bridge which spanned the river. It was at this moment, as the buggy moved at its fastest pace, that George Reeves hurled himself from the buggy, apparently with his handcuffs still on.

Castrup shouted, “George is gone!”

Seconds later Pete Huther leaped over the front wheel on the left side of the buggy and started running down the road in the pitch-black darkness after the outlaw, the little pistol the sheriff had given him earlier at the ready.

It was later speculated by Sheriff Castrup to a newspaper that the two outlaws, having been brought from Huntingburg to Jasper by this same route a few weeks before, had plotted on the train on their second trip where the best place would be to act on an escape plan, one, that if successful, would follow the pattern of their 1885 shootout with the two Dubois County deputies they eventually murdered.

According to the sheriff’s thinking, George Reeves was going to lure Huther, “a small and not strong man,” down the darkened road where Reeves could overpower and take his pursuer’ weapon, kill him, and then come back in the darkness and kill the other two officers and free his brother.[xxxii] If this was indeed the plan, the first part worked to perfection.

As Huther ran blindly into the darkness, he shouted for Reeves to stop. The outlaw just laughed somewhere up ahead. In frustration and fear, Pete shot several times in the general direction of the laughter. The Jasper tailor might have been small, but he was faster and much younger than the outlaw. He continued to follow the sound of footfalls and the increasing clamor of heavy breathing. Still, he might not have caught the escapee if Reeves had not thrown down his cigar, its glow telling Huther he was going in the right direction.

Huther caught up with the brutal escapee just as Reeves turned to climb up a bank at the side of the road. Placing the revolver in his back pocket, the little tailor grabbed Reeves by the foot and pulled him back to the road, not realizing that Reeves had now freed one of his hands from the cuffs. Falling back from the bank, Reeves came to straddle Huther.

The outlaw probably could not believe his luck. With his fury driven by the adrenaline rush of his escape attempt, Reeves began to use the heavy set of manacles dangling from his one wrist as a deadly weapon, swinging it high up in the air and then bringing it down in the direction of Huther’s head,

Huther, meanwhile, dunked his head this way and that, avoiding the deadly strikes but grunting in pain when the heavy cuffs made solid contact on his chest, arms, and shoulders.

Huther quickly realized he was losing the battle with the larger stronger man and would soon be beaten to death. Somehow, he managed to draw his revolver from his back pocket, hoping he had not used all the bullets in his earlier pursuit.

He had not. The last bullet left the chamber before Reeves could bring the heavy end of the handcuff down again, the bullet going through the outlaw’s heart.

Huther, himself reeling with adrenaline, smashed the pistol up against Reeves’ head several times before he finally realized his adversary was dead.

Having just finished a fight to the death and taken a man’s life, the quiet young tailor went into shock. Walking unsteadily through the dark, he came back to the carriage, “panting and trembling with excitement,” telling the sheriff, “I shot him and he’s up there in the road.” Then Huther turned to John Reeves and explained, “I had to do it, or he would have killed me.”[xxxiii]

Castrup now took the lead, getting the sheriff’s deputy to stay with the body while he and the spent Huther took John Reeves to the county jail in Jasper. A coroner’s report the next day exonerated Huther of any wrongdoing.

Two days later, George Reeves’ body “was placed in a coffin with his coat on, showing where the fatal bullet had entered.” It was viewed by hundreds of curious people all day long at the town undertaker’s place before being buried late that afternoon. Local newspaper accounts of what followed was in keeping with the American culture’s previously noted amour with outlaws. The Indiana English News observed, for example,

The body of George Reeves was buried Sunday in the potter’s field at Jasper, many thousand attending. No clergy responded and a village quartet sang “Nearer My God to Thee,’ as the sexton filled in the grave. The surviving brother was permitted to view the body as it lay in the undertaker’s shop, and he was then returned to jail. He broke down as he looked upon it, remarking, “The only friend I had in the world. I am friendless in a world where there is no such thing as justice. Perhaps I have made mistakes, [but] I do not deserve all this.”[xxxiv]

If John Reeves’ words were a play for sympathy, they, and a wife and small child in the courtroom, worked to a great degree. Later in June, a jury found the surviving Reeves brother guilty but only sentenced him to two to twenty years in prison. He was out in two years.

The hero of the story, J. P. “Pete” Huther, also received newspaper treatment, one paper suggesting that his actions were not as brave as they seemed. “No one in the buggy knew of Reeves’ ability to cast off his handcuffs at pleasure. This ignorance,” suggested the paper, “added to Pete’s boldness.” The next day after Huther had taken down the outlaw, the Jasper Herald, however, placed the drama and the Jasper tailor’s role in it in its proper perspective. “Had the last shot failed to work so well, it is doubtful if the two Reeves boys would have been tried and that three corpses would have been brought to Jasper instead of one—and that the body of George Reeves.” The report added that Huther was,

“a man of slight built, weighting but 128 pounds and is 5 feet and six inches in height. His antagonist was a man of about six feet in height and weighting perhaps 165 pounds. That the odds were preponderantly against Huther in a hand-to-hand struggle with Reeves is apparent, and his last shot failing, Huther, and not Reeves would have been the dead man. His friends congratulate Mr. Huther on his lucky escape and admire his courage.”[xxxv]

A few bizarre newspaper items came out of the dramatic event as well, both involving ghosts. The Indianapolis News reported that the Reeves brothers’ father, old Doc Reeves, who was thought to have died sixteen years before, just after the murder of the two Dubois County deputies, was reported to have been seen “in the eastern part of the county. If the old man is still alive, many fear that he is here to avenge the death of his son George, and to rescue John, who is being closely guarded night and day.”[xxxvi] Nothing came of this report, other than a few comments about a possible ghost. And in the fall of 1901, several months after the escape attempt and shooting in the Patoka Bottoms, there was a reported sighting of George Reeves’ ghost around the Briarfield bridge.[xxxvii] That story too faded.

On a final note, the little tailor, J. P. Huther, would later be appointed as the Jasper postmaster and remained a valuable citizen of the city of Jasper and the county of Dubois well into the 20th century. One odd feature concerning his postmaster reign involved his requiring the city mail carriers to wear sidearms, a holdover perhaps from his traumatic fight with the outlaw, George Reeves in 1901.

[i] Richard Meyer, “The Outlaw: A Distinctive American Folktype.” Journal of the Folklore Institution, 17(2-3) 1980, 94-124.

[ii] RandyMills, “A Terror to the People: The Evolution of an Outlaw Gang in the Lower Midwest.” Midwest Social Sciences Journal: 23(1), 2020.

[iii] Naugatuck Daily News (Connecticut) May 13, 1901.

[iv] Jasper Weekly Courier, June 5, 1885.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Elfrieda Lang, “German Immigration to Dubois County Indiana, During the Nineteenth Century.” Indiana Magazine of History, 41(2), 1945

[vii]Indianapolis Journal, June 29, 1885.

[viii] Jasper Weekly Courier, September 24, 1886.

[ix] Indianapolis Journal, June 29, 1885.

[x] Ibid., January 31, 1879.

[xi] Jasper Herald, May 31, 1901.

[xii] Jasper Weekly Courier, May 31, 1901.

[xiii] Indianapolis Journal, June 29, 1885.

[xiv] Courier Journal (Scottville, Kentucky), August 2, 1895.

[xv] Elfrieda Lang, “German Immigration to Dubois County Indiana, During the Nineteenth Century.”

[xvi] The Jasper Weekly Courier, December 16, 1898.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] The Jasper Weekly Courier, December 25, 1896.

[xix] Ibid., May 17, 1901.

[xx] Mt Vernon Register News, January 22, 1901.

[xxi] See for example, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, January 22, 1901.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] The Jasper Herald, January 25, 1901.

[xxiv] The Jasper Weekly Courier, January 25, 1901.

[xxv] The Jasper Herald, February 22, 1901.

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] Ibid.

[xxviii] Ibid., May 17, 1901.

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] English Crawford County Democrat, May 16, 1901.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] The Jasper Weekly Courier, May 17, 1901.

[xxxiii] The Jasper Herald, May 17, 1901.

[xxxiv] English Crawford County Democrat, May 16, 1901.

[xxxv] The Jasper Herald, May 17, 1901.

[xxxvi] The Indianapolis News, May 16, 1901.

[xxxvii] The Jasper Herald, November 8, 1901.