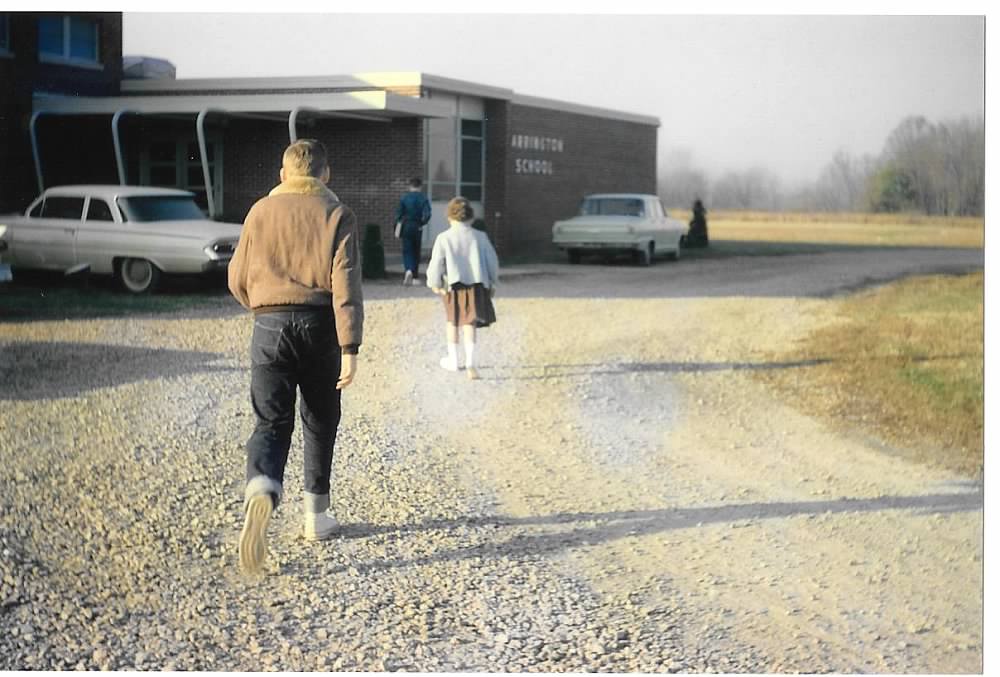

There were fifteen rural grade schools in Jefferson County, Illinois, when I was growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, and the school I attended, Farrington, was the smallest. The school had eight grades in three rooms and offered only boys basketball as a competitive sport. It certainly provided a wonderful learning environment with lots of personal attention, but it was a poor place to be prepared for playing high school basketball, a sport at which my often moody dad sorely hoped I might excel. This wish first became evident to me when Farrington had a peewee basketball game. Third, fourth, and fifth graders were mixed; divided into two teams; lent old, tattered, dark blue uniforms; and sent out to play one night before the older boys had their B and A team games. The peewee boys played in front of a crowd of excited parents, our legs pale and hairless. I was so big in fourth grade that none of the regular basketball trunks on hand fit me, so I wore a pair of my father’s faded blue swimming trunks.

I was surprised when my father rather than my mother took me to the event, surprised even more when he talked to me about the game. He had rarely paid much attention to the things I was involved in, but now I could tell he was excited.

The contest bordered on chaotic, with several unschooled players running with the ball instead of dribbling, and one, who shall remain unnamed, running in the wrong direction to try to score. As it turned out, not one of us was able to score a single basket. The only positive aspect of the awful affair was apparently the game’s entertainment value—the small crowd roared at our antics.

It was shortly after the peewee game that my father, with the help of Grandfather Mills, put up a basketball backboard and goal on the front of our garage. It was here my dad’s dream of my playing high school basketball became mine as well.

There were major hurdles to this wish.

Farrington kids went to Bluford High School, and although the high school was small compared to other schools, it was like going to the big city for us Farrington folks. Playing varsity basketball there seemed a remote and sad dream for a Farrington kid like me. The main obstacle was Bluford boys had already been turned into amazingly fundamental players, playing like a smooth well-oiled machine, by one of the best grade school/junior high coaches in southern Illinois—Max Allen. Someone not trained in this already existing system when they walked into the Bluford High School gym was typically doomed to ride the bench and perhaps get into a late part of a game.

Nevertheless, we Farrington Eagles gamely played the rural schools in the county, games we rarely won. My eighth grade year, 1964-1965, we beat only a tiny Catholic grade school, St. Mary’s from Mt. Vernon, a team that lacked a gym in which to practice. We beat them by two measly points. Two of my eighth grade classmates, Garry Gene Pierce and Butch Ellis, were good ball handlers, and Garry was a decent shooter, but both were short. George Breeze and Steve Gregory, also on the short side, were the other two A team starters. It did not help that almost all the teams we played were having great years.

Being almost six feet tall, I was the main go-to guy for the Eagles. My arms were so long, I could keep getting a rebound under the basket and put it up again and again until it finally went in. It was an awkward, ugly process, but I racked up large point totals doing this. I also blocked several shots each game with my long, gangling arms. Always big—like a Baby Huey, the cartoon character who accidentally knocked down friends when playing—I knocked opponents around underneath the basket without any awareness of my strength.

Our coach, David Stewart, apparently grew tired of watching me gracelessly throwing offensive rebounds time after time toward the basket until they finally fell through.

“Yo, Mills. Over here,” he hollered from across the gym floor at the end of one particular practice.

I scampered over to where he stood cradling a basketball under one arm.

“I’m going to show you some pivot moves under the basket and how to shoot a jump shot,” he said, and he flipped me the ball.

And so my lessons began. I put my heart into learning these two things, hoping they would help improve my game before our last contest, a home game against Bluford Grade School. My dad had already told me about how good they were. “They have a seventh grader named Ed Case who shoots 65 percent from the field,” he told me. I wondered if the gleam in his eye as he spoke involved a wish I had such a skill.

Max Allen almost always had the best grade school team in the county, and that year was no exception. The Bluford players came flying out of the dressing room looking more like young men than grade school boys. We Farrington Eagles watched with our mouths open while the Bluford team pumped in shot after warm-up shot from all angles without missing, the net swooshing and dancing during the entire performance. Then I turned and saw Coach Stewart was standing there just as dumbfounded as we were.

Coach Stewart never grew loud with us, but Coach Allen either stomped his foot and hollered at his players or moped on the sideline the entire game. That in itself was traumatizing. It was almost like being at home with Dad when he was in one of his moods. Only the tiny size of the Farrington gym, throwing off their fast-break rhythm, kept the Bluford players from beating us to smithereens. I got far fewer than my usual number of points but blocked several shots under the basket. I saw by the surprised looks on their faces that this was something the Bluford guys were not used to.

Dad was pretty grim after the game, not even saying something about my blocking several shots. I knew why. He saw what I saw—the guys I’d be in competition with if I went out for basketball at Bluford High School.

There was one positive exception to the rough eighth grade basketball season. During the county tournament, a newspaper article in the Mt. Vernon Register News emphasized that I had scored twenty-five of our team’s forty points. In that game, we lost by only ten to the eventual runners-up in the tournament, Rome Grade School. Of course, Bluford won.

It was the first time I saw my name listed in a box score or spoken of in a sports narrative, an event that brought unexpected elation.

I was also surprised and excited when Dad, before I could do so, cut the item out of the paper and put it on his nightstand for safekeeping. My eighth grade class graduated in the spring of 1964, and that fall eight scared Farrington freshman students, along with the older Farrington students traveled by bus to Bluford High School. On first glance, one would have given me very little chance at playing much high school basketball and even less chance of starting varsity. Through a number of unusual and unexpected circumstances that I relate in my book, An Almost Perfect Season: A Father and Son and a Golden Age of Small-Town High School Basketball however,I ended up starting varsity my sophomore year at Bluford High School. I was one of the very few Farrington boys to start varsity for Bluford up until that time. It was a small and select group this Farrington kid will always be proud to belong to. Starting varsity as a sophomore would not be the last amazing surprise in my playing days as a Bluford Trojan. More amazing events were yet to come and you can read about them, and more Farrington Grade School stories in An Almost Perfect Season, coming out this fall.