It was fifty years ago this week, but seems like only yesterday. I was the first of my parents’ children to go away to college. This alone probably explained the solemn expressions my mother and father wore the day they helped me move my things into a tiny Jordan Hall dorm room at Oakland City College on September 2, 1969.

Once my parents drove away, leaving Indiana and returning to southern Illinois, I faced a new and scary turn in my life in a strange place where I knew not a single person. Incoming freshmen moved into their dorm rooms a few days before classes started, attending orientation meetings, but were mostly left to wonder around the wooded and all-but-empty campus. So, country-boy that I was, I left Jordan Hall to explore my new world.

I walked among the many empty buildings and in the shadows of ancient oak trees and twisted, gnarled catalpas, listening to the clamoring cicadas, my fear of failing at this new place growing into a tormenting monster. How could I, an unsophisticated kid from Southern Illinois ever figure out how to navigate college, especially on my own? I soon returned to my dorm room and its unnatural air-conditioned chill, soaked in sweat, my spirits heavy.

I did possess a talisman of sorts.

One of the most important things I carried up to my freshman dorm room on moving-in day was a folded up and worn letter announcing a scholarship I had received earlier that spring from Oakland City College. The letter possessed a strange and tangible potency and even my practical-minded mother told me to keep it close by in case college officials forgot about the award. The letter read in part, “Congratulations! You have been awarded the President’s Scholarship of tuition and fees for the 1969-1970 academic year. The scholarship will be renewable each year you maintain a B average.”

The scholarship was given to the limited number of students selected, according to the school catalogue, in recognition for their academic excellence, leadership abilities, or outstanding talent. While my family was overjoyed and proud that I had received such an award, I carried great doubts about living up to such expectations. In a time before cell phones and the Internet, the simple standard mentioned in the last sentence of the congratulatory letter, “The scholarship will be renewable each year you maintain a B average,” would come to take up much of the focus of my family’s frequent letter correspondence during my first year of college.

My main concern during those first few weeks of college was a horrible case of homesickness. Often, through the weekdays—hurrying to and from classes, taking notes, eating at the college cafeteria—I’d find myself thinking about the cling-clang sounds of dishes and of pots and pans in the family kitchen as Mom prepared a meal, about the sweet vague aroma of my father’s pipe, lingering in the air, announcing his recent presence. As I scratched down volumes of notes in stuffy classrooms about long-ago battles, impossible math equations, and the New Deal, I realized if I was home, I’d be working with my Grandpa Mills in the afternoons after school, helping with the harvest, taking in the dusty smells of picked corn and combined soybeans.

All of this nostalgic thinking brought an unexpected sadness that was so indescribable, I might as well have had a severe case of an exotic flu. But instead of medicine, I checked my dorm mailbox daily, desperately hoping to see a fat envelope from home nestled behind the little glass window. My mother’s letters, like an umbilical cord, became my only connection to my boyhood home. In one of her first letters, she wrote,

The soy beans are turning out real good here. Hope the weather lasts so they can get them out. Marshall [my older brother] dreads driving to the elevator in Wayne City in the old ’49 Dodge truck Grandpa got to haul beans with. Too slow for him. After the big downpour the other day, Horse Creek is out of its banks.

After reading the letter, I walked to the edge of town and sneaked into a farmer’s bean field. The leaves on the stalks were just beginning to yellow. I sat at the edge of the field, my legs crossed underneath me until darkness and the mosquitoes chased me back to my dorm room.

In my mother’s very first letter, most of the themes in which she would dwell upon that entire year appeared.

Here’s why I’m writing you so soon this week—I wanted to tell you unless you’re feeling much better you should go to the nurse. When you write me, be sure to tell how you’re feeling so I can either quit worrying or worry more. Be sure to get more sleep! Also, study. I hope you like all your classes and teachers. Be sure to write your assignments down and pay attention. You know you can’t call Sherry Wilson for help now.

Sherry was a distant cousin with wonderfully bright red hair I had attended high school with and who was as precise and diligent as I was absent-minded. I had often called her in the evenings through the school week to get forgotten assignments.

Perhaps the thing that made me miss home the most during those first weeks of college were references in the family letters to farming and to seasonal changes back in southern Illinois. In a letter dated the last day of September, 1969, my mother wrote, “The trees should be really pretty if you come home this next weekend. There are still a few green ones on the maple next to the smokehouse although they too are turning fast.”

In today’s language, my mother and father would be called helicopter parents, the kind who hover over their college son or daughter in an attempt to ensure success. Before I went to college, they had done their best to steer me away from potential pitfalls like my wasting money or dating the wrong girl. They doled out cash to me that I had made working for local farmers and limited my use of the family car. Growing more aware of the way I’d been sheltered often annoyed me greatly when I’d sit at my dorm room desk, working on a class assignment or when going to The Oaks sandwich shop to get a bowl of chili and a grilled cheese sandwich. But then, I’d suddenly feel guilty and miss home.

One of Mom’s early letters, dated September 13, 1969, certainly revealed this smothering tendency to hover. Her letters always came on plain unscented white paper, nothing expensive or fancy.

I hope you’ve calmed down enough to start sleeping and studying. Keep your bed made and your room neat. Don’t fall in love yet. It has not been long enough. Now, Randy, get up and eat breakfast. It’s only a few minutes earlier to get up and you’ll feel better all day.

Of course, that was wise counsel, and, of course, I did not follow up on any of her advice.

My mother’s ongoing concerns about my possible lack of resting and studying were, in fact, well-founded. By October, I had discovered many new and exciting things that made my homesickness recede to the back of my mind, only appearing occasionally if I saw something, like a tractor moving through a field that reminded me of home.

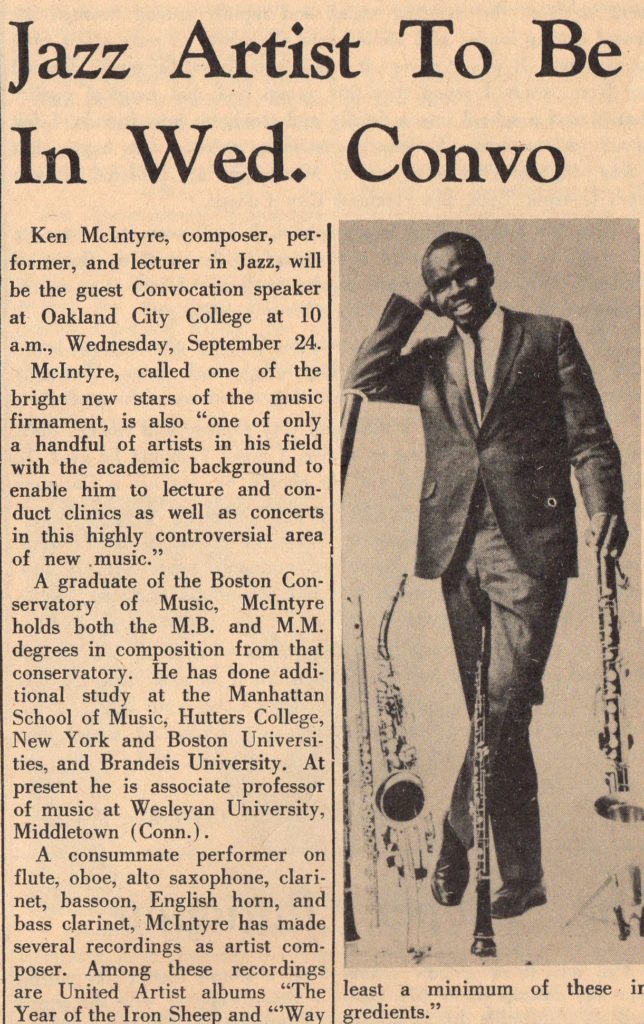

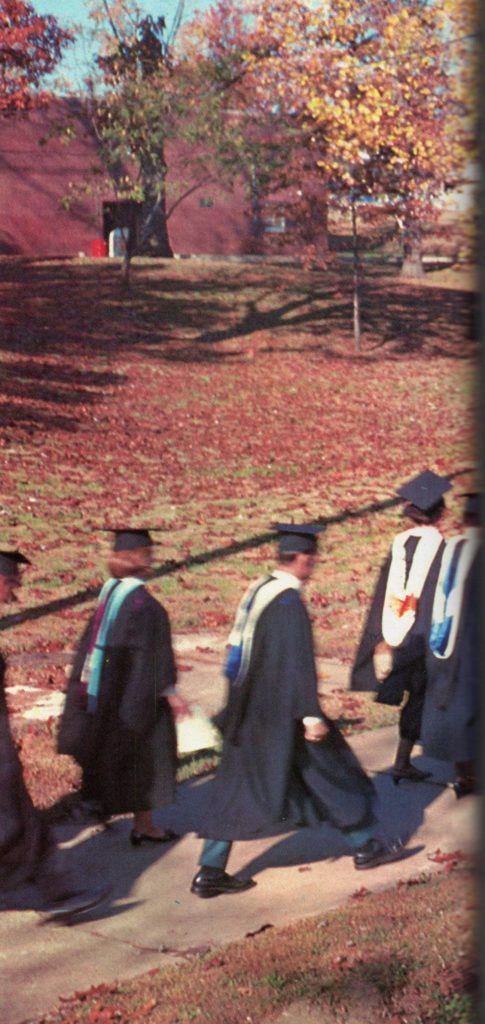

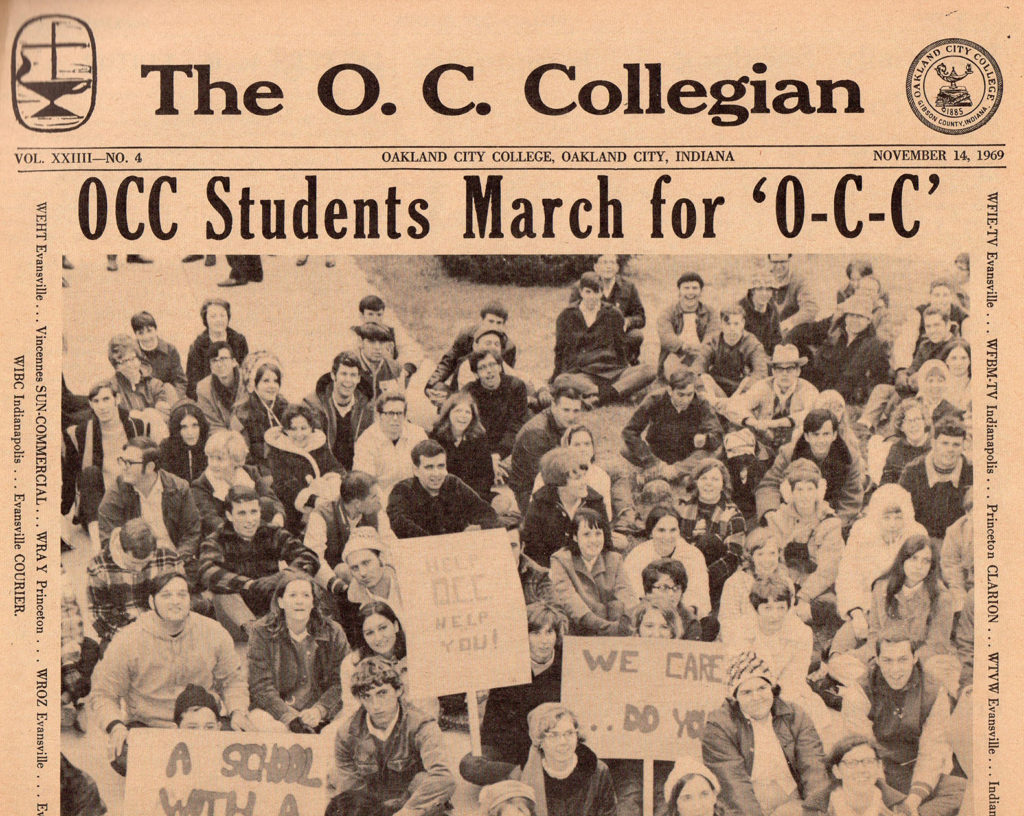

The campus always seemed to have something going on. Instructors were knowledgeable beyond any of my prior experiences with teachers and the things I heard about and discussed in class began to give me new perspectives on life. I also conversed with fellow students from all over the nation and from other countries after classes, and with a group of Jordan Hall fellows, the latter bunch in long sessions deep into the night, arguing about politics and religion, about the Vietnam War and national racial tensions. We’d often eat popcorn while we bantered, or maybe an occasional slice of an ordered pizza when one of the fellows received some unexpected money from his parents. At college convocations, I personally met and conversed with a United States Senator, as well as the former prime minister of Hungary. I met and listened to a famous jazz musician, chose whether or not I would get up early in the morning to attend a particular class, and ate out frequently at a nice local restaurant full of pretty waitresses called “Johnson’s,” until my monthly “play money” Dad gave me ran out.

For the first time, I realized that I had ideas that might run counter to my parents’. It was an intoxicating discovery.

By the second month of school, I had become heavily involved in SCA, Student Christian Association, and now traveled frequently on the weekends. I had also begun running around with several fellow dorm mates who, like me, enjoyed the outdoors. We spent many hours exploring the thousands of acres of abandoned stripped out coal mines in the area, looking for fossils and swimming in the large deep pits of water left by the coal mining operations. I also began going home with dorm friends on weekends, especially to Kentucky and Missouri where both the people and the lay of the land there reminded me greatly of my home back in southern Illinois. It probably did not help my parents’ worrying that I wrote home about this time, telling the family,

I’ve had so many adventures lately I wouldn’t know where to start. You wouldn’t like them anyway if I told you about them. Maybe I’ll tell you some other time.

While my mother was relieved to see I had gotten over much of my homesickness, she had probably not counted on my sudden reveling in all the new-found freedom. My plans for exploring a wild cave in Kentucky with a Jordan Hall friend, Richard Orr, one weekend brought forth one of my mother’s longest letters that year.

My family got wind of the cave exploring idea when they noticed how, at the end of one weekend visit home, I had packed a plastic hard hat to take back with me to college. The fear in my mother’s narrative may have also been partially driven by her having grown up in a coal mining town in southern Illinois where roof rock collapses often took lives. In part, she wrote,

Randy, don’t you be going into any caves with that silly helmet. That thing is only plastic and would be no protection at all. Dad worried after you left about you getting lost in a cave. Seems like you can do the most foolish things sometimes. Why can’t you just be normal? Try anyway. Write and call sometime this week and don’t do anything stupid, like getting lost in a cave. Bye.

As it turned out, cave exploring would be the least of her or my worries that quarter. Math, my old nemesis in high school, turned out to be particularly frustrating. Mom had been correct. I could have really used Sherry Wilson’s help. Perhaps too, I assumed that the instructors would grade like my high school teachers, giving me some slack for good attendance and cooperation. Of course, my mother warned me, “Don’t wait until the end of the quarter to study and then have to cram so much.” Before the school year was over, my mother would write me many times, encouraging me as I struggled to learn one of the hardest lessons I would ever receive, a story I tell in an upcoming issue of Connections: The Hoosier Genealogist. I’ll keep you posted when it is available.