While waiting for the release of my Bluford basketball book, I thought I’d send out a story for all the folks who love my brother, Marshall Mills.

In looking back through old family photos and reading the chatty letters my mother wrote to my brother Marshall and I while we were in college, it suddenly dawned upon me how my family carried on a great and often difficult romance with cars. With such romance in the air, my brother and I were often at odds. This rivalry was further driven by another reality—we were Irish twins, less than a year apart and, consequently, we often fell into being fierce competitors. I was the younger, so Marshall typically held the upper hand. Being older, he had also always been part of my life, a constant shadow, larger than me, until I caught up and then barely passed him in size, as if the sun had slightly changed its angle and shrunk his shadow a wee bit.

Another factor that intensified our family’s interest in cars was that our father, Keith Mills, left the drudgery of full-time farming in 1954 and started selling Ford cars in Mt. Vernon, Illinois, for G. B. Holman at Holman Motor Company. From that time on, my family looked forward to seeing the introduction of all the new Ford models each year in October, like waiting for an exciting and elegant fashion show. Doing this event, my family had lively discussions about the changes made in the new models and, as time passed, it became obvious that a generation gap was emerging on the subject. My parents seemed less enamored by the fancier elegant models or the stud muscle cars. No dreams of Lincoln Continentals, Thunderbirds, or Mustangs for them. They wanted cars that were first and foremost functional—the ones most likely to gets us from point A to point B in a reasonable fashion—cars such as the dependable Galaxie 500, Fairlane, and Falcon models.

I was somewhat neutral on the matter of car styles. I just wanted everyone to be happy. Just the thought of someday having a car was enough excitement for me.

Marshall, on the other hand, had very specific tastes when it came to cars, wanting both sexy and muscle. So, as you might imagine, our family’s dances with cars were not always happy affairs.

Among the scores of photos our mother took of Marshall and I when we were a couple of years beyond toddler age, one set stands out—the pictures of a shiny pedal-driven car our parent bought for us with my brother driving it in every snapshot but one. The exception featured my little sister at the wheel, apparently asleep. I seemed to be stationed in a metal lawn chair the entire time, a scowl on my face.

Marshall was such a capricious force in my life, one minute playful and affectionate and the next a holy terror. Yet, it was Marshall who was my constant companion, the person who gave me a special nickname one day as we played with our toy cars on a dirt patch just west of the smokehouse, an endearing name he called me the rest of my life—Doc. The day we got the pedal car, however, was not one of my brother’s better days. Not only did I not get a turn in the car, but Marshall also managed to put a deep dent in the shiny new pedal car that very first day we had it.

And so it went.

Marshall and I both possessed restless spirits, but our responses to this restlessness diverged, the gap widening over time. Marshall found peace in doing things—fixing a loose bicycle chain, sneaking to Grandpa Mills’ tractor parked in some way-off field and taking it for a spin, seeing if he could get away with something. He was always on the move, fleeing from boredom. I, on the other hand, was pulled inward—reading books, collecting rocks, daydreaming, trying to stay on an even keel while navigating a capricious sea of constant emotions and worry.

This restlessness was slaked somewhat by my brother’s and my access to driving. Though Marshall had begun much earlier than I did, like most boys growing up on a farm, we had both driven tractors and then pickup trucks in fields and on back-country roads before we got our driver’s licenses.

We were also abundantly blessed when it came to cars.

We had a main family car and another older and less attractive model my mother drove, all Fords of course. As a perk of his job, our car salesman father also drove a handsome demonstrator car, usually a loaded Galaxie 500, and proudly kept it at our home, parked in a spot where anyone driving by could get a good look. Over the years of my boyhood, Dad would probably drive at least a dozen different ones of these demo cars, allowing our family to show up to church and other community events in a shiny new vehicle.

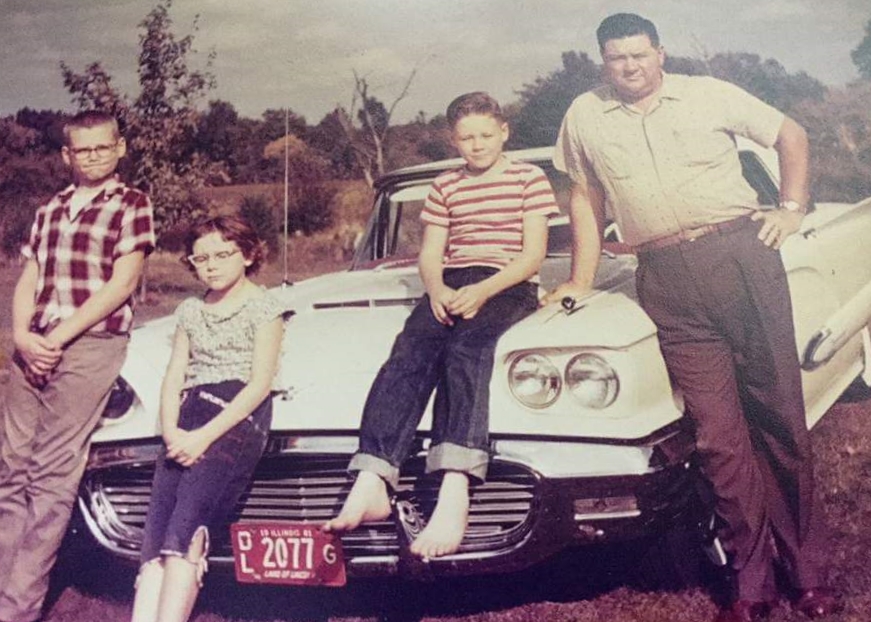

There were special car occasions as well, like the time Dad brought home a beautiful white 1960 Thunderbird for a weekend, one that we traveled in one Sunday afternoon to our Newell grandparents. It was the only time I remember my parents being excited about driving a fancy car. Even then, by the end of the day, Mom was complaining about the lack of practicality of the car. “Too crowded,” she said.

Mostly, and to Marshall’s great disgust, we were destined to be around plain Jane cars with low performing engines.

Dad would also bring home and keep older beat-up vehicles we called work cars that he kept around to haul junk in, take to the fields, and keep the mileage off the family cars. The first of the work cars I remember was a 1956 Desoto with soaring tail fins, triple taillights, and push-button transmission. This was long before Marshall and I were supposed to be driving.

One Saturday morning Mom and Dad took their usual trip into town, taking our little sister, Karen, with them. My brother and I stood on the road and watched the family car disappear down a hill to the west of our house, like a ship going over the horizon. Marshall went over to the Desoto and boldly climbed in, ordering me to do so as well. I just thought he was going to turn on the radio, a real treat in those days since dad did not think we needed our own transistor radios.

Instead of reaching for the radio, Marshall went for the keys, starting the damn car.

“Doc, this is going to be fun,” he said.

Marshall turned the wheel to miss the maple tree and headed south toward our barn, his entire body elongated as he pushed his right foot down on the gas pedal, his head barely able to see over the steering wheel.

We skirted past the barn, tearing into the back part of our forty-acre field, a billowing, zigzagging rooster tail of dust signaling our whereabouts. He drove back and forth over the terrain, whipping the car around like a carnival ride. I held tightly onto a window grab strap, what Grandpa Mills called an “Oh Shit!” strap, scared and exhilarated at the same time.

And it was fun.

More junk cars from the dealership Dad sold cars for came and went after we got our licenses and started working in the fields with Grandpa Mills and for neighboring farmers. We named each successive car after the first names of previous owners—Irene, Velma, Frankie, and Raymond. Once, this practice almost got my brother into trouble when he told our high school bus driver, who was also a garage-owning mechanic that Irene’s rear end had gone out the day before, failing to recall that the bus driver’s wife was named Irene.

Irene, Velma, and Frankie were boat-like 1961 Ford Galaxies with the big flat fins on the back. They were flat-out ugly. Raymond was a black little 1964 Ford Falcon with a stick shift on the column. The Falcon’s previous owner, Raymond Coffee, was Sharon’s, my half-sister’s, uncle. When Dad first brought Raymond home one late afternoon, Marshall and I soon discovered a sealed mason jar full of a murky liquid hidden under one of the front seats. Turned out Raymond had apparently used the jar on long trips when he did not want to take the time to use a public restroom. The other three cars were somewhat embarrassing to drive to school but possessed more horsepower than Raymond and were great for driving to the hay fields, or so I thought until I made my first big driving mistake.

Once I had built up a reputation as a hay-field worker, farmers started depending on me to get together my own handpicked hay hauling crew. On one job, after finishing an especially grueling day, the crew talked me in to taking them to Leonard Wilson’s General Store in Velma to cash checks and grab some sandwiches and drinks.

On the way there crouched a rough railroad crossing that I was too busy showing off—weaving in the road, playing chicken with the ditches—to slow down for.

The sound of the car’s muffler being torn off was like a scream of anguish.

After the torn-off muffler cooled down, we pitched it into the ditch, covering it as best we could with weeds. I took all the crew to their homes, reassuring them that I’d face few if any consequences over the missing muffler. I even gunned the motor a couple of times as we tooled down the road for their pleasure, the lack of a muffler making the car engine sound like a roaring muscle car. All of this was bravado and lies.

There was no telling what my moody dad would say or do when he heard the loud ragged noise of a car engine minus its muffler. My only hope was that he would not see or hear the car as I coasted in, my foot off the gas pedal to soften the sound. Once the missing muffler was discovered, he would more than likely suspect that my risk-taking brother had done the deed.

I coasted in as planned, parked, and shut off the engine. I had not been paying attention in my rearview mirror. Dad nosed in behind me, home early from work. He stepped out of his car and walked over to where I sat in Velma.

“Start up the car,” he ordered.

My worse car blunder, bad as it was, was nothing compared with Marshall’s first known car catastrophe. But even before that event, an episode that stands as an iconic tale among our many family stories, Marshall was hell on wheels. He’d take out one of the work cars, or sneak out the family car, or, worse still, Dad’s demo car and hot-rod it up and down the back roads, leaving bold matching patches of black tire tread, backing the car up and then slamming the transmission into first gear, flooring the gas pedal as he did so.

Almost all the local teenage boys carried out the same ritual, as if marking their territory, but every time Dad saw one of those places, he’d confront my brother, who’d grin and deny it.

Dad would turn and look at me, his eyebrows raised, and I’d shrugged my shoulders, an accomplice to my brother’s latest escapade.

Riding in a car with Marshall was always an adventure. Marshall would joyfully turned down abandoned dirt lanes that were supposedly impassible and somehow popped out the other side, the car’s undercarriage decorated with the woody stems of branches, the front side mirrors with garlands of leaves. Once, on pure impulse, he swung a car abruptly into an overgrown field, driving willy-nilly, dodging gullies and saplings, seeing how far he could get before he had to turn around and find his way out. I made him stop when we finally popped out on the main road, got out of the car, and walked home.

Speed was yet another temptation Marshall gave in to when it came to cars. I hated to ride with him when he was in the mood to see how fast he could go on a particular stretch of road, topping a hill at such speeds that it felt the car might go airborne.

As noted, there was one epic event with Marshall and a car the family all came to know. One summer, in 1966, after a torrential rain had knocked all the farmers out of the fields, Marshall decided to go to the Horse Creek bottoms to see the floodwaters. Dad had just purchased a new family car, a shiny turquoise-colored 1965 Ford LTD with low miles, warning us not to drive it. Marshall initially planned to take the Irene work car to see the backwater, but temptation was too strong. Dad was in town working, and Mom was busy helping Karen with a 4-H party. Marshall, perhaps out of guilt for what he was about to do, volunteered to look after our little five-year-old brother, Marty.

Five minutes later Marshall and little Marty were in the creek bottom, Marshall driving our new family car, plowing through the six inches or so of water that covered the road. He drove fast enough that water sprayed up both sides of the car. To calm Marty, he told him to pretend they were in a speedboat.

Bored after going back and forth down the water-covered road several times, Marshall backed onto a field road bridge he assumed a few inches of water was covering up, only to find the car sliding into the deep backwater. The flood had washed the bridge away.

The car floated for a minute or two, moving away from the road, water coming through the seams in the doors. Marshall grabbed little Marty and pulled him through the driver’s-side window just as the car suddenly nosed into the water and sank with one big loud gulp.

Once ashore, Marshall put Marty on his shoulders and ran up the road until he met a car. The driver, a local farmer, took them to a nearby sawmill where the owner threw a chain on one of his tractors and took my brothers back full speed to the submerged car.

Marshall dove under the water a couple of times, anxiously feeling around in the murky water, before he found a place to hook on the chain.

I was in the barn, lifting weights, when a tractor came chugging into our driveway, pulling our waterlogged car. When Marshall opened the door of the car to let himself and Marty out, water spilled out in a muddy wave, along with a hapless carp.

I suspect the phone call our mom made to Dad’s workplace that day was one of the hardest calls she ever made.

Once he got his driver’s license, Marshall always got his choice of available cars—usually Mom’s car or one of Dad’s nice demos from the car dealership where Dad worked. Marshall also had the guts to take a car whenever he wanted, a practice I could never seem to perfect. Once he started driving, there grew frequent tales of Marshall carousing in town at night, along with constant stories about him drag racing. I noticed there was a big increase in long black peeling-out tire marks all up and down the road we lived on. Dad, an unlit cigar clamped in his mouth, frequently complained about how quickly tire tread disappeared, but never caught Marshall in the act of peeling out.

I got my license the next year, but the best I could hope for in the car department was the Raymond work car. When I did take a car, I drove around home mostly, studying the rural landscape, watching it change through the seasons while I pondered the mysteries of life or thought about some girl while I listened to the radio. Sometimes I’d stop and park by an old cemetery or an old abandoned home place, wondering what these people’s lives had been like, ghosts filling up the car. My only time to drag race was a Sunday afternoon contest with Randy Gutzler on his pony. We raced down a block of a Bluford side-street. Raymond preformed gallantly, but the pony won.

When I went out-of-state to college, I thought for sure I’d finally get my own car. This would have been in the 1969-1970 school year. Marshall, meanwhile, was attending Rend Lake Community College, just a few miles down the road from our house and had access to our family and work cars for easy transportation.

I knew having a nice car on campus would bring me status and would also allow me to drive home for the weekends. I also figured I deserved one, given how careful and diligent I’d been as a driver, unlike my brother, who, it seemed to me, tore up and down the roads like a demented race car driver. Mom even gave me hope in an early letter she wrote to me while I struggled in my first few weeks away from home that such a thing might indeed be possible.

Another beautiful day. I think Grandpa might soon start on the beans. He and Marshall went last night to look at an old truck to buy to load beans in.

By the way, there may be a car in your future, but don’t know if and when Dad will buy you an older car. He has a 1964 Comet in mind but found out the insurance would be $165 for six months if you were the principal driver so he’s cooled off a little. Keep your fingers crossed,

But in the next letter from Mom, I received stunning and distressing news, news that was placed unexpectedly in the narrative, as if she wished to ease my disappointment, or was just ashamed about what was transpiring.

By the way, Marshall is finally getting himself a car if everything goes o.k. Dad is trading the white one for a red Ford, of course, 1967 two door hardtop. Of course Marshall is happy about it. I hope it’s a good car. He’s working for Don [a local farmer] today and will be every spare minute to pay for the car.

Mom then added a quantifier to the news. “Marsh says he will share it with you but you know Marsh, he may forget”

I certainly knew better when I read about the sharing idea. Marshall had demonstrated his tendencies long ago with our little pedal car. I’m sure Mom knew too, but wanted to find a way to ease my certain disappointment about the matter. Second born syndrome, however, soon kicked in—I knew my parents would be paying up front for my brother’s vehicle and I wondered how they were going to pay for his car insurance when they couldn’t pay mine.

In Mom’s next letter came more frustrating news. “Dad got the new car deal finished up yesterday, so we officially have a bright red car sitting in the car now. Marsh got it polished up but hasn’t cleaned it on the inside yet.”

“Good for him,” I thought.

I caught a ride home from college the first weekend I could to see the new car Marshall was supposed to share with me. It was a candy apple red Galaxie that dad had indeed gotten a good deal on. While the color would have been considered a girl getter, the lack of horse power, it only had a small 8 cylinder 289 engine, left much to be desired in my brother’s eyes.

“Doc, it’s a damn dog,” he told me.

Marshall took all the hubcaps off the black walled tires in an attempt to jazz up the car’s looks, but like an unwanted bride from an arranged marriage, the low performance car never came to suit him. And there was absolutely no talk about me getting to use the car.

While Marshall was getting his own car, I was either bumming rides to and from Oakland City College over in Indiana, or hoping my parents would drive over and get me on late Friday afternoons. I would have even settled for driving good old Raymond. Meanwhile, another letter from Mom reminded me of my brother’s love for speed and his discomfort without it. “Beans are turning out real good. I hope the good weather lasts so they can get them out. Marshall dreads hauling to Wayne City in the old ‘49 truck grandpa got. The old truck is way too slow for him.”

Eventually, my parents grew weary of driving me the six hour round trip to and from school and I was finally allowed to drive the family’s second car, “Old Blue” a couple of times a month while my brother continued to drive “his own car” whenever he wished.

Marshall transferred to Southern Illinois University the next year, keeping his red car at his dorm. I continued to drive one of the family cars whenever I could to the out of state school I attended. Meanwhile, one of mom’s letters to me told of a new car saga, one I hoped at the time would finally open my parents’ eyes to how hard my brother could be on a car.

I hope Marshall doesn’t have any car trouble this week. I never know what to expect next. His car seems to be running ok now. Bob Smith wants to trade his Super Sport for Marsh’s car. But Dad won’t hear of it because the insurance would be higher and also the gas bill.

One of Marshall’s letter to our Mom I recently read told his side of the story.

Mom,

I had an 8:00 class and went out to my car and it wouldn’t start. I had to take the battery out at the Argonne [dorm], put it in a box and carried it 20 blocks to the gas station. That was bad enough, but I missed a test in Ag Prices. I guess the stupid klunker’s got a short in it somewhere. This car of mine still bugs me. I wish Pop would trade it off before we have to spend a chunk on the transmission. When you get in it, you don’t know how far it’s going to take you or how much it’s going to cost. I guess I’ll have to wait until I’m 21 and brother I’m counting the days now. I’d rather wait until I’m 21 anyway so I could half way get what I want. I don’t reckon Pop can remember when he was young – it’s been so long. Tell pop when he does trade it off, I’ll stay at home and let him pat me on the head and be a good boy. I was so mad I couldn’t see straight yesterday when the car wouldn’t start. If the local army recruiter would have been in walking distance, I would be in the army now.

Marshall

Shortly after this letter from my brother to my mom, a car and I also caught the attention of our mother in one of her letters to me, this after I sled off an icy road coming home from college while driving one of Dad’s demonstrators. The latter was the rarest of events.

Perhaps out of guilt for not helping me buy a car, Dad had finally let me drive one of the car dealership’s better demos to school to keep for a an entire week, a green high performance Ford Galaxie that quickly caught the attention of fellow students at the college I attended. When the accident happened, I was proudly bringing several other students from the area back home for Winter break and their parents were picking them up at my house.

I was a mile or so a from home when I began to do something very Marshall-like, turning the steering wheel ever-so-slightly to make the car skid, then turning into the skid to right the vehicle. One of the girl riders in the back seat screamed the third or so time I did it and l laughed at her and said, “There’s no way you’ll go off in a ditch if you know what you’ll doing.” At that moment, wicked karma struck, the car going into a 360 degree spin and flying backwards into a ditch.

This time the girl riding in the back seat let out a scream that could have woke up the dead.

I ran as fast as I dared on the ice covered road and got a farmer to come and pull the car out with his tractor, hoping my parents wouldn’t discover my transgression. Mom, however, apparently got word of it from one of the parents after I returned to school.

Randy

You need to be more careful when you’re driving on ice. I can’t believe you would be so careless. Probably talking to Becky or not watching the road. You can be so absent minded at times. I’m kind of disappointed in you but I believe you’ve learned an important lesson. Of course I won’t tell Dad.

Dad apparently found out anyway. I never got to drive the cool green demonstrator to college again, being demoted once more to driving the ugly dark blue second family car.

Luckily, my time in the car fiasco limelight was short-lived. Soon, I was sucked back into the family drama of my brother’s situation, Mom writing me,

Marshall just called from Benton and his battery has gone bad again and he is going to have to buy a new one down there. That means he won’t make his two classes today. He is missing so much, I don’t see how he will pass anything. Please pray for your brother. He needs all the help he can get.

I didn’t know it at the time, but Marshall certainly had another thing to worry about besides a car. Mom wrote of this worrisome issue in a letter to my brother.

Marshall

You got a letter from the Draft Board yesterday wanting to know how come you were still in your 2nd year at college. If it was because you lost credits in transferring they wanted to be advised by the college. So I wrote the draft board and the college for you and asked S.I.U. to tell the draft board you had lost credits. So you’ll know what’s going on. Boy, they are breathing down your neck aren’t they? Anyway I think it will be o.k. since I wrote them.

Having figured they had taken care of the draft problem, my parents turned back to Marshall’s ongoing car problems. For my part, I believed it was bad karma from all the times Marshall had driven cars so roughly. Dad suggested Marshall take his car to a dealership Dad worked out of occasionally to get the troublesome car fixed, but Marshall’s next letter home explained why he thought this would not work.

Hi mom,

Got a bad cold today. Yesterday I got wet two times and do I feel it. I didn’t go to class today, so I’ll have to go over to Miller’s and get his notes. Tell Pop that I don’t want to take my car to Bert’s because if I bring another car down, I’ll have to get a temporary parking permit. Due to the fact that I’m not even supposed to have a parking sticker, that wouldn’t be too wise. When I applied for my sticker, they told me that all I could have was a sticker which only allowed me to have my car at the Argonne and not on campus. When I went to get it, there was a real cute girl there and I asked her if she would give me a fifteen dollar parking permit instead of a yellow permit. She smiled at me and let me have it but she charged me twenty dollars for it but it’s worth it. If I had to walk to class, it would be as far as from home to Clyde Ellis’s in distance. I think I can cripple the old klunker around and when it quits, that’s when I quit. It sure is hard on me to stay cooped up in four walls all day when I know I could be out on a tractor someplace or out hunting.

The 2×4 that uncle Dean put in the side of my car has started rattling. I hope it don’t slip down because if it does, that big dent in the side will come back. I don’t know which is worse – my car, school, girls, or the army. Anyway, I got plenty to worry about. HA.

Well, I think I’ll go to the Sands and see this girl I met in Philosophy. Don’t worry, I’m not going to drive but walk.

See ya Friday,

Marsh

My brother’s mention of the 2×4 that had been placed in the side of the car by our Uncle Dean who ran a car repair shop was another story. Marshall was backing up with his door open and hit something, springing the door so it wouldn’t shut right. Then, yet another car catastrophe fell, one discussed in another of Mom’s letters.

Dear Marshall,

I better write before I get busy and forget it. You’re probably still shook up. Bring all your clothes home and anything else of any importance. About your car – Dad is acting rather admirably about it. That word means nice. He called Uncle Dean about it. A new fender costs $65. Dad figures it’s too bad to be straightened and will need a new fender. He said time it was fixed and all it would run around $130. You know your car insurance only starts paying after you pay the first $100 so there’s not much use in turning it into the insurance. But just in case it did turn out to be a lot more expensive, like $200, and you had to turn it into the ins. go ahead and get the police report down there and if your roommate is still there and has a driver’s license, better get the number and his home address.

However, Dad doesn’t plan to turn it into the ins. at the present time, but you can’t tell what may develop. If your roommate can help pay on it, it sure would help.

Try to concentrate on your exams and be careful coming home. There will probably be a lot of traffic and it could get slick any day now. The pretty weather won’t last forever. In fact, it’s raining here today.

I too continued to be drawn into the dire car situations, with Mother writing me,

Looks like another hectic weekend coming up. Marshall called last night from Carbondale and said his transmission is going out again. He may not be able to drive home. Anyway, Dad nor I never slept very good last night for worrying about it. Randy, if you get a ride home, don’t plan any running around cause Dad’s sort of depressed now about the car situation. You know what I mean..

Another letter indicted how difficult this time was for the family, having many cars but few that ran well—water water everywhere and none to drink.

Dear Marshall,

The old black Mercury quit on me last night as I came home from the store in front of Huston’s house. Mr. Houston brought me home. Dad went back in the blue car and pulled it home with a chain. I had to guide the Mercury and was scared but we made it o.k. It’s something wrong with the transmission. A valve is sticking or something. Anyway Dad had to drive “Old Blue” to town today to work.

We didn’t sleep very good last night for worrying about your car. Recon it will make it home? Dad said to come on home at noon Friday and don’t try to work at FS any this weekend. Grandpa and dad took the Mercury back to Bert’s yesterday. They pulled it to the city limits and drove it to the garage. If your car quits you’ll have to call home and we’ll come get you. Be careful on that interstate. Do you think it will make it home?

I’ve got to get busy now. Guess I’ll clean the upstairs today. Don’t forget to bring your empty Pepsi bottles home. If your car did happen to quit be sure to lock the car because you’ll have it full of clothes. Dad said it should make it home if you’d be careful. Course he doesn’t know for sure so be careful and call if you need to.

Love, Mom

All this worry about cars was soon eclipsed when Marshall dropped a chemistry class at SIU and unintentional became one hour short of being a full-time student. When the Jefferson County draft board became aware, Marshall was sent a draft notice. Mom and Dad all but worried themselves to death over the situation, easily forgetting about car problems. I too was gravely concerned, forgetting all about the red car business myself. The war in Vietnam, however, was just starting to wind down and Marshall ended up in the National Guard. When he finished his basic training in 1972, he came home, dropped out of college and began farming full time. With the money he made, he bought his first real car, an all-new beauty of a Ford Torino, good karma finally coming his way.

That next year, my parents finally bought me my own car—the ugliest brown colored Ford Galaxie you ever saw. But like a plain but good wife, it would serve me well as I started my own journey into adulthood, getting me faithfully from point A to point B for many years and teaching me the value of a good car.

One last car story. Surprisingly, my non-introspective brother, Marshall, was the very first member of the family to grasp what my coming to Oakland City College ultimately meant. He took me back to school one Sunday afternoon in his red Ford Galaxie, the one Mom said he’d share with me, helping me carry my stuff, including a pair of heavy dumbbells, up three floors to my dorm room, complaining every step about “all this crazy crap you keep bringing from home.”

Feeling bad about Marshall having to help me lug my barbells up three flights of stairs, I went down with him to the parking lot to thank him for bringing me back to school and to say goodbye.

He opened the car door to his red car and turned toward me, raising one arm in the beginning motion of a goodbye wave, but stopped suddenly, the palm of his hand turned out, like a blessing.

Fighting tears, he managed to say, “Gosh, Doc, we sure are going to miss you.”