The Story of how our Mother found her Vocation

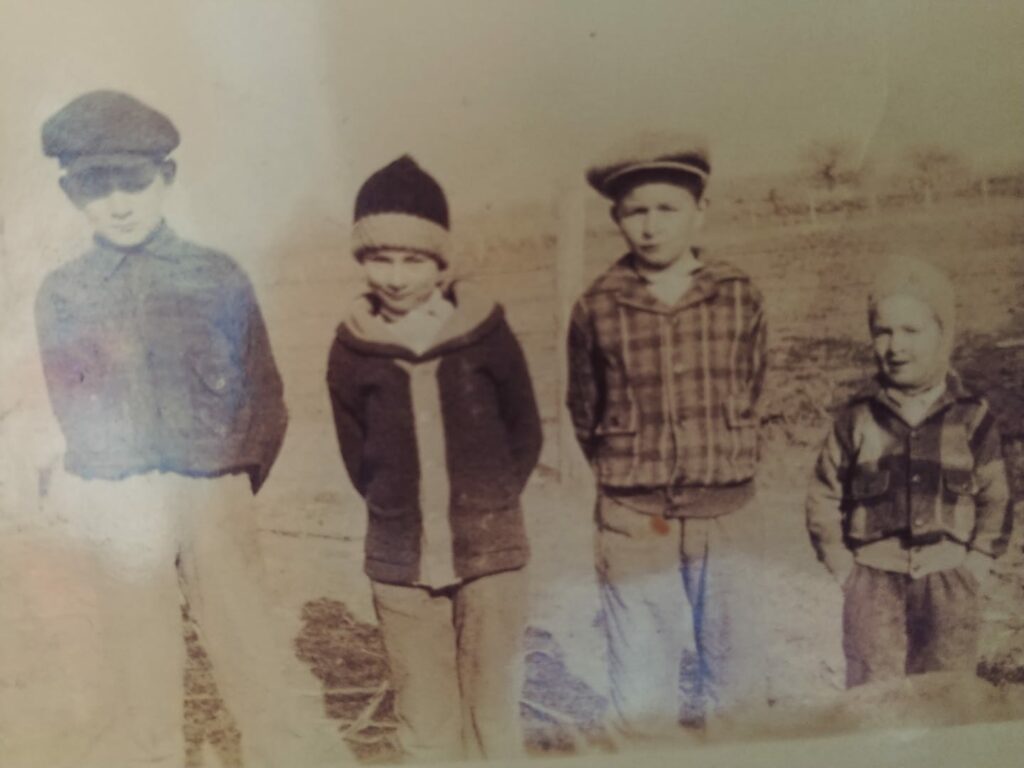

This January marks the seventh year of our Mother’s passing. She was born Mary Alice Newell in 1927, just outside the little town of Waltonville, Illinois, the same year Charles Lindbergh made his dramatic solo crossing of the Atlantic in the miniscule plane he named “The Spirit of St. Louis.” Like Lucky Lindy, our mother would have her share of adventures, although of a more subtle and quiet nature. Interestingly, we siblings knew very little of her younger-day exploits, a fuller awareness only unfolding after her passing.

There was certainly a reason for Mother’s reserve. Her people were a sweet but introverted lot, private in their entire demeanor, certainly not a people to tell elaborate stories. What stories Grandma and Grandpa Newell did tell their grandkids amounted to only a few repeated fable-like tales, stories like “the city mouse and the country mouse,” yarns that conveyed simple moral cautions.

Our mother was cut from this same cloth, giving little detail about her youth to us kids, although the few short accounts she did share at least contained a beginning, middle, and end. Not so, however, with one story Mom infrequently shared.

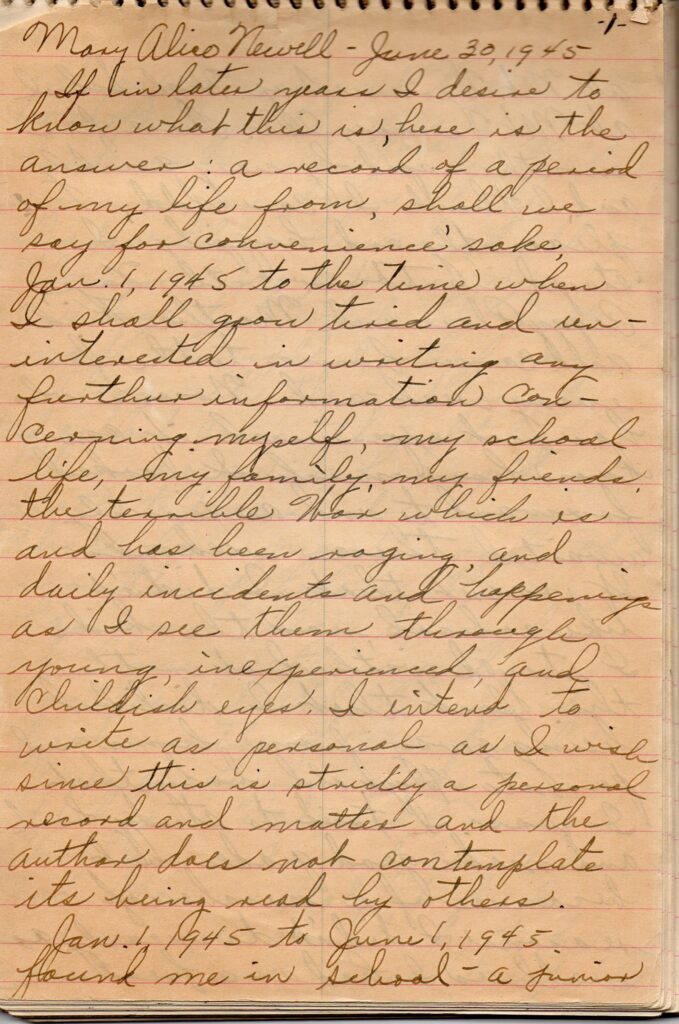

The story involved our mother’s short stay, after graduating from Waltonville High School, at Southern Illinois University in the 1946-1947 school year. Like the tip of an iceberg, so much more seemed left out than touched upon, with Mom always brief telling of the tale. Her quick shift to other subjects when talking on the matter only heightened our interests. All that changed after her death in 2013, when several important pieces of our Mom’s SIU story came my way. The material included two of Mom’s personal diaries, several forgotten family letters, an old high school yearbook, a 1946 Look magazine, and a few other forgotten artifacts packed away in an old lard can. These materials provided new and insightful context and clues to Mom’s SIU sojourn, allowing me to construct a detailed account that offers a sad but beautiful tale, the story of a teenager girl struggling to find her true vocation in the daunting social cauldron of family and community expectations.

“Her record is straight A’s.”

It is important to remember that the mid-1940s was a time when women were encouraged to take many of the male vocational roles that had been depleted by WWII. Our mother rode the crest of this circumstance, being able as a teenager to consider vocations beyond that of a housewife. Other factors would enhance this situation for Mother.

It is in her first diary, written during her freshman and sophomore years of high school, that our mother first spoke to her hope of becoming a doctor, an idealist notion that came to play a central role in her second diary. Part of the inspiration for her wanting to follow such a difficult track may have involved her natural intelligence and the resulting expectations of her teachers. Her diary showed she was certainly proud of her grades. After one school term, she noted, “I have several A pluses and the rest A’s on my report card. . . I find Latin hard but I like it.”

James and Vera Newell were especially happy with their oldest daughter’s academic performance, and Grandpa Newell eventually began pushing our mom to think about college. His expectations may have had much to do with his own disappointment in having dropped out of Northwestern University as a young man in 1906 and coming back to Waltonville to farm, another story we had often heard about in the barest of details and only as a cautionary story about there being no place like home.

Biology became Mom’s favorite subject in her freshman year, due in great part to her budding relationship with her science teacher, Mr. Kellett. At the very beginning of her first diary, Mom had written wistfully, “I wonder where Mr. Kellett is and what he’s doing. Bet he’s reading Man and Climate somewhere.” Because of the war, Mom worried about Mr. Kellett being called up for military service, writing, “I do hope Mr. Kellett will be back. He is by far my favorite teacher. My fingers are crossed.”

The admiration was apparently mutual. Deeper into the diary she related how “Mr. Kellett showed me how to use the microscope today while the rest of the class were finishing their Latin test as I was through. He says for me put the microscopes away after we get through with them. I hope I don’t forget!”

The most interesting episode between our mother and Mr. Kellett, mentioned in her diary, one that clearly demonstrated his vocational expectations for her, occurred at the end of her freshman year. She wrote how Kellett had approached her at a local diner in Waltonville and asked if she would be attending the senior graduation program. “He said, ‘sister you must be sure and come tomorrow night.’ I said I would. When he gave me my report card Friday, he asked me if that was a promise that I would come. I said yes again.”

The evening of graduation, after all the senior graduates had been given their diplomas and other awards had been passed out, Mr. Kellett stood up and announced there was a last recognition he needed to bestow. Mom wrote in her diary of what followed.

What do you think? An award to me for perfect attendance! I can’t remember all that Mr. Kellet said but on the back of my award he wrote “Another [future] valedictorian. Her record is straight A’s. She has the mental capacity to be responsible, to realize the value of time and to make A’s all four years and into college. She is blessed with good health which enables her to maintain a record of perfect attendance for 9 months regardless of distance or weather.”

Our excited mother then boldly added, “And I’m going to maintain straight A grades 4 years and into college!”

At that time, Mother also wrote a note about Mr. Kellett that was not in her diary but was found folded in the lard can with her diary and other materials mentioned earlier. The note read, “Mr. Kellett’s life would be an interesting subject for a biography. I might write one someday if I become able. At least it is an ambition I shall cherish until it has been realized. He has perhaps done more to mold my life and the lives of other students than anyone besides our parents. I love him for all he taught me, and I know he has done his part in preparing me for life.”

Early in her sophomore year, Mom wrote of another event that further increased the pressure of adult expectations. “I don’t think I mentioned it, but we took IQ tests this year. Of course, I don’t know what I made.” A few weeks after this, Mother was surprised when someone came into her classroom and told her to report to the principal’s office. She was certainly puzzled but not afraid. Her study habits and pleasant obedient demeanor had always made her every teacher’s favorite.

As it turned out, Mother’s IQ score had come back, and the high school principal wanted to give her the news. She was told her score was very exceptional. The information was kept quiet, although all the teachers soon knew of her high score. Waltonville had less than fifty students and some locals questioned whether the small high school could properly prepare students. Mom’s grades and IQ performance, however, gave a boost to the school’s academic status. Of course, our grandparents were pleased and excited even more about Mom’s possible professional future.

“I Tried to Study Hard”

At the beginning of her second diary, Mother found herself in a new and difficult situation. The summer before her junior year, in 1944, the town of Waltonville was rife with rumors that the high school there might shut down. The struggling school had only forty or so students and little in the way of extra kinds of classes, especially vocational ones. The school consisted of only three teachers and a teaching principal housed in five rented rooms on the top floor of the town’s aging grade school. On the other hand, nearby Mt. Vernon High School, located in a bustling town of over fifteen thousand, boasted over a thousand students and employed thirty-nine teachers. The school also offered a huge variety of courses including full vocational training, piano, journalism, Spanish and commercial law.

As it turned out, Waltonville High School did not shut down. However, our grandparents were concerned enough about giving Mom and her younger sister, Faye, a solid education that they paid both the tuition cost and money for room and board to send them to Mt. Vernon in the fall of 1944. The cost was certainly a heavy burden on the family.

The first section of her second diary, often written by the light of a kerosene lantern in an upstairs room of the Newell house, offers a powerful sense of growing ambivalence and tension in our mother’s life. Writing of her time at Mt. Vernon High School, Mom noted, “These months sped by very quickly and, I think I can add, pleasantly and happily. I stayed in town with Faye, Peggy Place, and Martha Kirk and came home to the farm every weekend.” But then she added an emotional and contrasting comment. “No one who has not ever experienced it can know how much I looked forward to and anxiously awaited those weekends home.” Certainly, this latter thought brings into question just how happy and pleasant the Mt. Vernon school experience really was for her.

At Mt. Vernon, our mother also experienced making less than sterling grades for the first time in her school life, a shocking event for a student use to being at the top of all her classes. She wrote of this upsetting circumstance in her diary, lamenting, “I tried to study hard and make good grades but because of a number of reasons I didn’t do nearly as well as I had as a freshman and sophomore at Waltonville.” So often analytical, Mom went on to speculate why. “Perhaps the greatest hindrance was a lack of a suitable environment for study. That with a hundred other things brought my year’s average to a B while I had made straight A’s before.” Less evident to our mother was the fact she sorely missed her home in Waltonville.

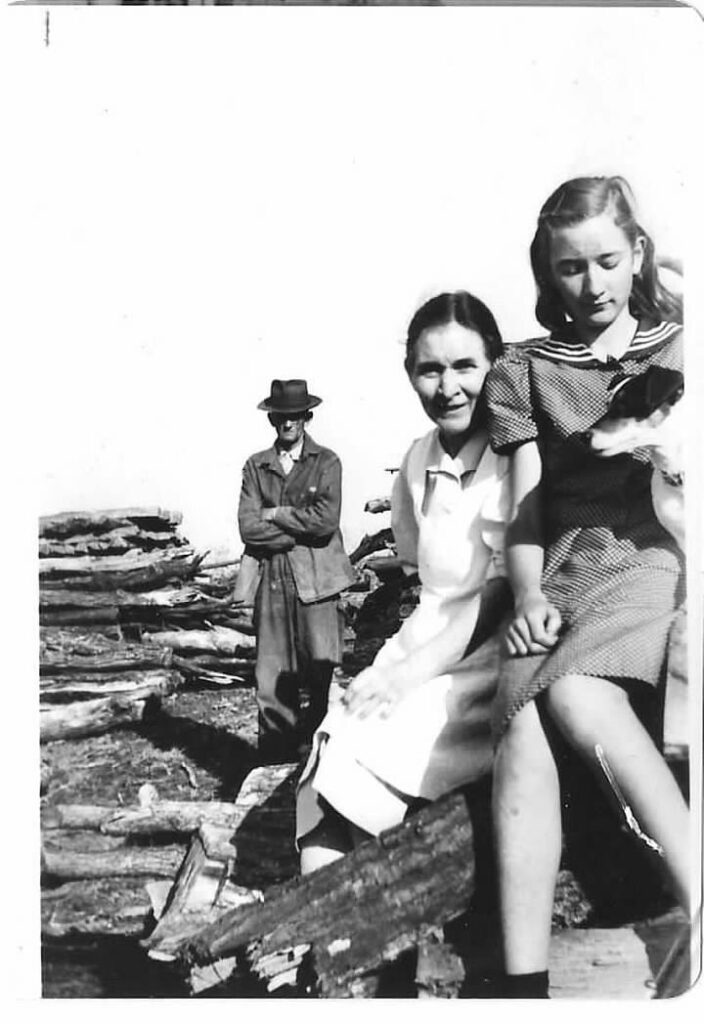

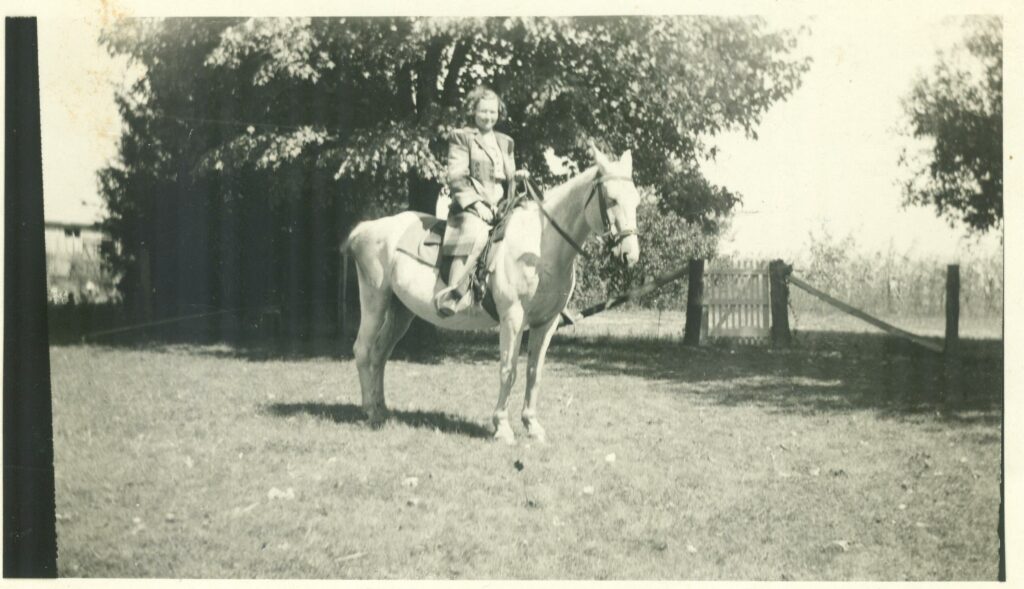

In June of 1945, Mother returned to the Waltonville farm for the summer. Her home had no indoor toilet or electricity, as her apartment had in Mt. Vernon, nor was there any of the social excitement of the big city. That early summer she helped her mother cook, carrying in wood for the wood burning stove, and helped wash clothes with a washer “you worked by pushing an apparatus back and forth by hand.” Despite the hard labor, she seemed overjoyed to be home. “It was good indeed to spend quiet evenings home on the farm without having to study or write shorthand all evening. Don’t get the idea that I disliked school at Mt. Vernon nor my studies. It was exactly the opposite, but I had merely grown a little tired of it all and a vacation was very welcomed.” But one troubling thought apparently loomed constantly on the horizon. “I have been busy here at home helping with the work some of the time and doing whatever my desire might be. Time, however, passes too quickly and I’ll soon be back there [in Mt. Vernon] studying again.”

The realization of having to eventually return to Mt. Vernon for school brought forth another problem for our mother, the question of whether to follow an academic track or a commercial track during her coming senior year at Mt. Vernon high. The latter would prepare her for being a secretary, while the former was more in line with the expectations of her Waltonville teachers and of her parents, who wanted her to try for something more advanced. She related in her diary how she had “a very hard time” in choosing her subjects. “I wanted to take chemistry and math but I just had to take shorthand and typing, and I couldn’t take both with the other required subjects. So, after deciding first on one thing and then the other, I finally chose English IV, American History, typing and shorthand II and salesmanship.”

There was a very practical angle to Mother’s interest in classes that were termed commercial studies at that time. This angle concerned the Newell family’s always precarious economic situation, a situation Mom wrote of in her diary. “I have vowed to do my best in the commercial subjects because I’ve come to the conclusion that before I can go to college I’ll need more money than my parents can give me and to earn it I must work.”

The last part of this section of her diary is more whimsical and captures a more romantic side of my teenage mother. “It is growing dark and soon I shall leave this state of fancy and pull myself back into the world of my family again. But I shall write more and I hope it is soon for I love so much to put these thoughts into words which are most persistent in my mind. So, I take leave of this work until I once again visit the world I love the most.”

“Not daring to tell myself”

The second section of Mom’s second diary is dated February 10, 1946. Eight months had passed since the writing of the first section with its rather idyllic ending. Mom was now in the last term of her senior year in high school. She begins the section by revealing what was for her an earth-shaking event—the unexpected appearance of her authentic self and its unexpected consequence, her returning to Waltonville High school.

Last July, after a month’s vacation, I decided to work at Mt. Vernon. I obtained a position as a clerk in Woolworth’s and started working at the candy counter. I rented a room on South 9th street at Mrs. Rupand’s. At first it was very thrilling and I was completely absorbed in doing my best at the store. I only made fifteen dollars a week but that seemed like a fortune to me then. Busy as I was, the two months until time for school to start again passed very quickly. Faye and I had planned to stay at Mrs. Rupand’s and go to school at Mt. Vernon again. But about two weeks before school started I, very surprisingly, made the decision to go back to Waltonville my senior year. Even I do not understand exactly just what prompted that decision. It came upon me suddenly one day while I was working at the store. At first, I merely played with the thought, not daring to tell myself I would really go back to Waltonville after a year at Mt. Vernon. Then, suddenly, I decided finally and completely.

Her parents’ unrelenting wish that our mother graduate from Mt. Vernon High School greatly concerned and worried her. But she announced her intentions to come back to Waltonville anyway, causing a colossal battle to ensue. “My mother begged and, at first, my father argued, but my mind was made up.” Now in touch with some inner power, Mom went even further in the fight, bringing her little sister into the fray. “After explaining the idea to Faye, she too decided to go to Waltonville.” When Vera Newell saw her oldest daughter’s decision was final, “she too gave in.”

Mom was gravely concerned by what others might think and say about her unexpected decision not to return to the more prestigious Mt. Vernon High School, but she carried out her plan “without an explanation to anyone—for how could I explain to anyone else when I didn’t understand it all myself.”

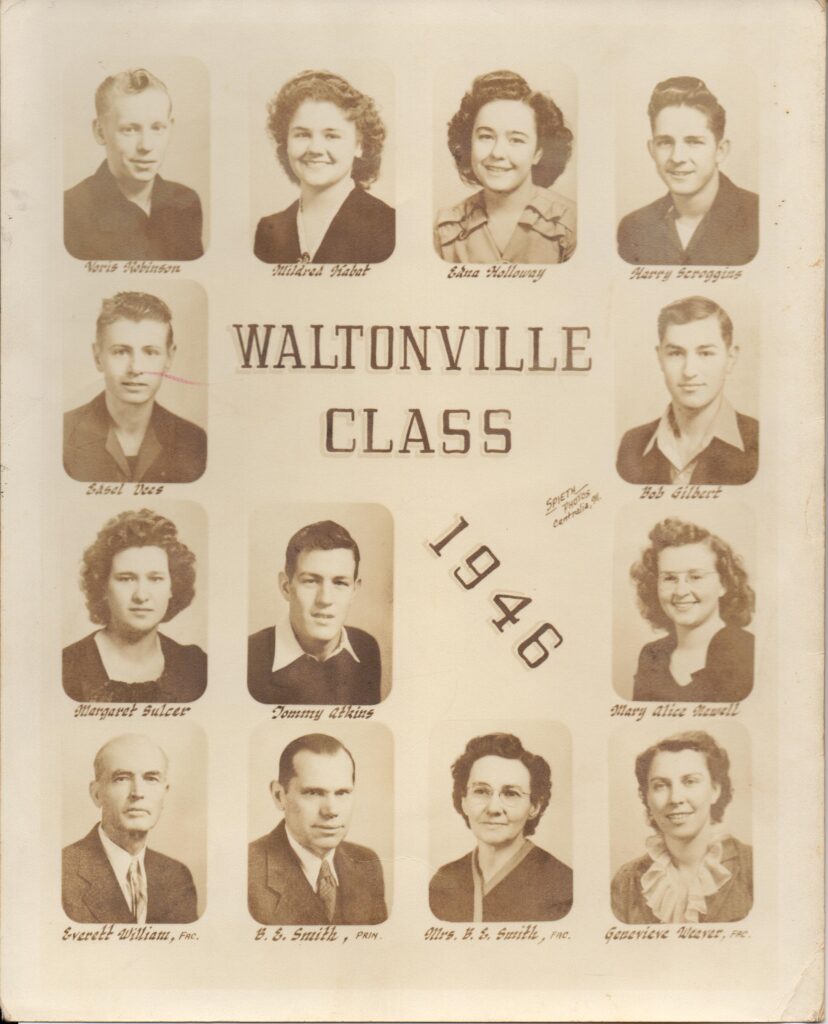

The dust seemed to settle rather quickly over our mother’s fateful decision and actions. She certainly seemed happy with her hard-earned choice, writing, “We started back to school in September. It was wonderful to see all my Waltonville friends again—the ones I knew as freshmen and sophomores. It brought back so many memories. I liked the teachers—Mr. Smith, the principal, Mrs. Smith, Mrs. Weaver and Mr. Williams.”

There was a sad element to her return, however, the absence of her beloved teacher, Mr. Kellett, who had gone to the military. Mom, however, was philosophical about the circumstance, writing, “Of course it wasn’t the same without Mr. Kellett, but then you can’t have your cake and eat it too.”

Another disappointment also crops up in Mom’s diary upon her return, the reality of Waltonville’s academic limitations. “The subjects I took were American History, General Math, English IV and general business,” she complained. “I regret I couldn’t have had a bigger choice of subjects but those were the only ones I hadn’t already taken. I wish I could have taken five subjects but anyway, I shall graduate with eighteen credits.” Soon, however, many truly happy and pleasant events occurred at Waltonville High, happenings which made Mom content with her choice of coming back to school there. She gave a great amount of space in her diary reminiscing about that year. “The main events at school were the carnival, at which Millard Kabot, my best friend, and Bob Dillard, a freshman, were chosen queen and king and the senior class play. It was so much fun getting the play up and giving it. I enjoyed it immensely. . . . Weenie roasts, skating parties, movie parties and ball games all added to the fun I’ve had this year at school. I’ll always remember the ball game at Bluford and how it rained so hard on us on the way home in an open truck.”

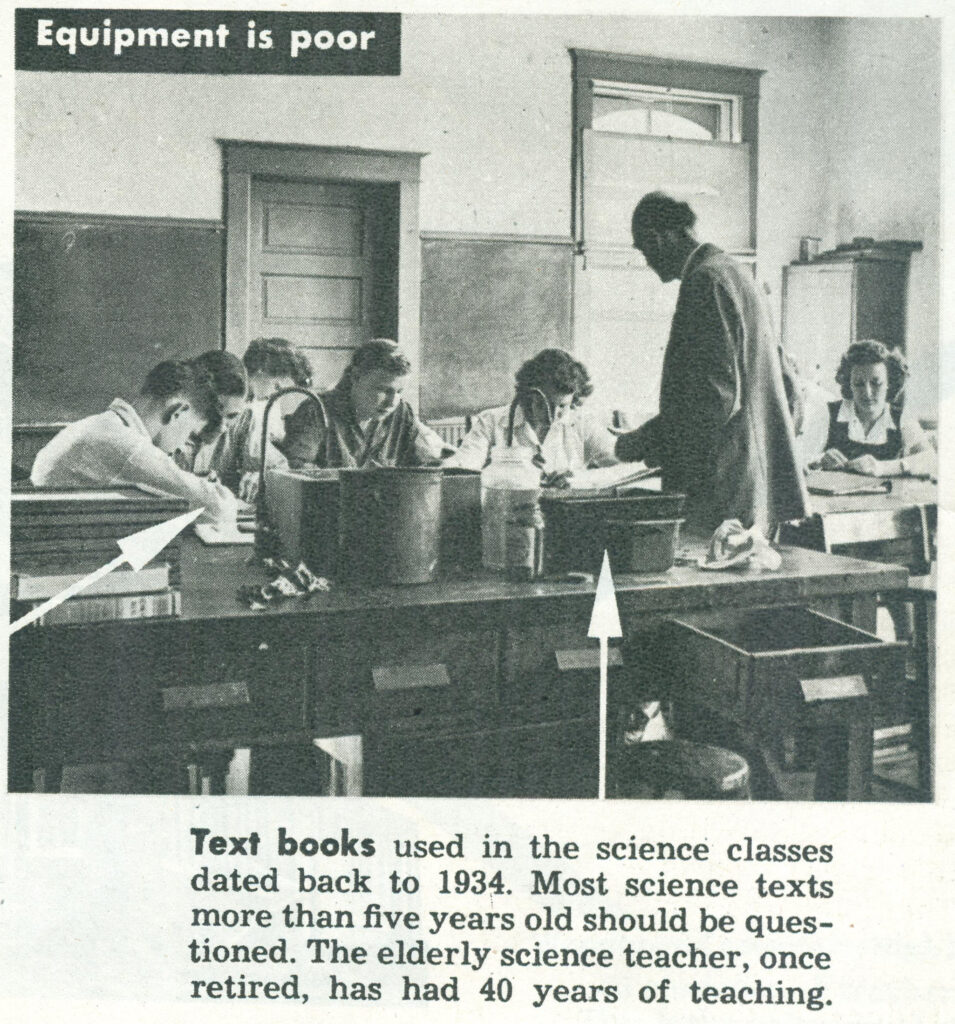

There was one dark spot on her wonderful year, one that she oddly did not even touch upon in her diary. In the spring of 1946, Look Magazine contacted the school board with exciting news. At that time, the magazine was a general-interest publication with an emphasis on photographs and was second only to Life magazine in national circulation. The magazine asked for permission to do a full-length story on little Waltonville High School. When the big day came, everyone dressed up for the visit. Photographers went around to several classes, taking photos of posed, dressed up and very serious looking students.

Mom appeared in one photo, sitting, where else but in the back of the science classroom, her eyes glued to a book.

A suave reporter interviewed several students and the entire school board, including Marion Newell, the chairman of the board and Mom’s cousin. The community was ecstatic and proud that the world would soon get a glimpse of their little school. Their excitement soon turned into anger.

In a long-detailed article containing many photos, Look magazine offered Waltonville High School as the prime example of what was wrong with thousands of small rural American high schools. The article was titled “Grass-Roots School Board.” It was a vicious attack. The article opened by asserting, “Our nation is haunted by thousands of skeleton high schools.” The piece lay the blame for this problem at the feet of local school board members “who are uninformed and victims of petty pride. Thousands of these so-called worthless skeleton high schools were being kept open by such boards,” Look complained. The magazine finally declared that schools like Waltonville should consolidate with larger schools to better help students achieve success.

While the article had merits, it seemed critical to the point of being vicious and one-sided. Positive ideas about the benefits of a small school culture, for example, were not offered. Nor were any quotes used from Waltonville students, teachers, or board members about what they felt, and thought was meaningful and important about their little school. It was a lengthy and devastating article, but one that the community quickly put behind them. The community probably reasoned, and correctly so, that there were thousands of little Waltonville type schools out there in the rural countryside and that Waltonville graduates had always accomplished much in life. Of course, someone like our intelligent mother was a prime example of this latter thinking, the best example possible.

“I shall obtain my goal”

As her senior year drew to a close, Mother turned to another theme in her diary—that of life after high school. Pondering her vocational future seemed to hurl her back into a part of herself vulnerable to others’ expectations.

Next Friday I shall take a college entrance examination to compete for a 4 year scholarship. I have a very small chance of winning, but I want to try anyway. My grades this year have been A’s but I feel awful dumb if they were not, considering the easy subjects I’m taking. I’m not studying this year as I should be. I’m going to try to do better from now until school is out. I have so much room for improvement and I want to be able to work in a professional field where I can help people. I feel I’ve been having too good a time at school and as a result my lessons have suffered.

Despite her worries, Mom received the scholarship, and, as high school graduation grew nearer, the question of vocation became an overpowering issue. Mother’s concept of success, that of entering and doing well in a professional career certainly fulfilled her parents’ and others’ expectations. But something still seemed amiss. Mother lamented in her diary, “As graduation comes closer and I realize I’ll be out of high school, I’m haunted by the question of what I shall do.” Some of her concern, as suggested in her writings, might have involved the family’s financial situation.

When I wrote here last June, I wanted to be a doctor. That desire is no less urgent now, but it is not the foremost idea in my mind. I can accept a scholarship which amounts to four years training at a teacher’s college in Illinois if I’ll be a teacher. I have decided to accept it. I feel I must have a college education before I can start to do anything. I won’t take the scholarship just as a means to go to college and then not teach. I’ll be a teacher. I prefer now to teach science in high school. Perhaps I can go to [medical] school later, beyond the four years. Then, if I still desire to be a doctor, I can earn the money. I shall strive to obtain my goal.

This is the first time Mother spoke of becoming a science teacher, an idea on which she elaborated. “I find that I now have a strong desire to teach school and I have a feeling I may wish to make it my life’s work. I believe for the right person it is a wonderful attainment.” This is followed by yet another ode to her favorite high school teacher, Mr. Kellett. “Not everyone possesses a ‘teacher’s personality,’ the kind of personality that causes one person to radiate the desire to learn to others. Mr. Kellett had it and I believe he gave it to me.” She added, “I feel teaching would give one a deep satisfaction to know he was helping others to fit themselves to win the ‘race of life.’”

“Just being with family”

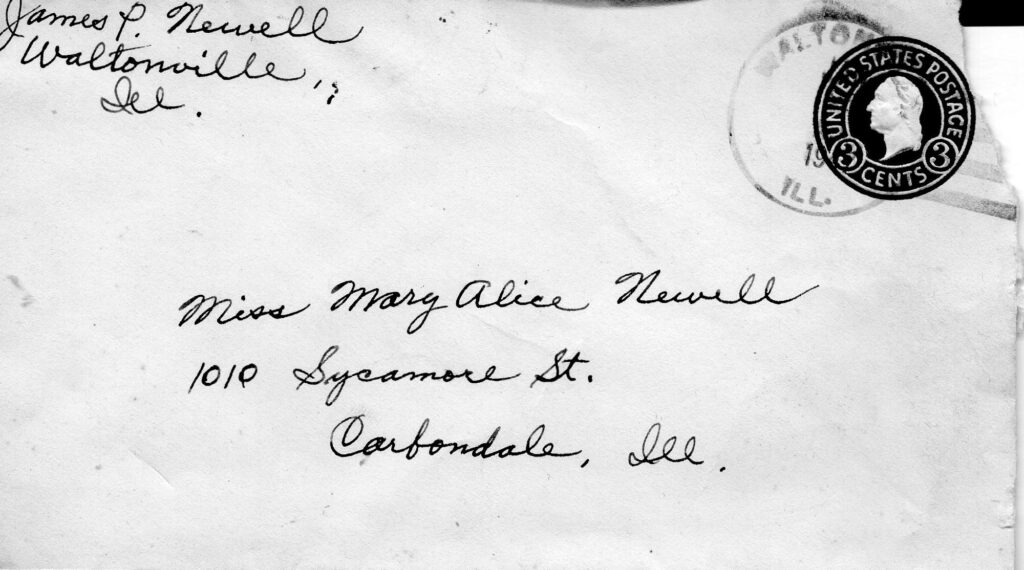

There are no artifacts suggesting how our mother felt the summer before she left for Carbondale to begin her college adventure. She planned to room with Waltonville classmate Margret Sulcer. Her best friend from high school, Millard Kabot, and another classmate, Edna Holloway, would be staying nearby. The presence of these friends guaranteed Mom would have a bit of home-away-from-home to help her with any possible homesickness.

Edna Holloway wrote Mom in mid-July about their upcoming adventure. “You know, I can hardly wait until school starts. I believe we will have a lot of fun, but I am afraid I will also get homesick.” The latter point was prophetic. SIU Carbondale was only a fifty mile or so physical journey from Waltonville, but another world away culturally for Mother and her three friends.

That summer Mom worked at a surprisingly satisfying job as a secretary and continued to write in her diary. “I went to Mt. Vernon and did typing for Pollock Abstract Company. I certainly enjoyed the work and I believe I was successful because the Pollocks seemed to hate very much to lose me when I left. I learned a lot about people and about life in general as well as office routine.”

There was another very practical up-side to her experiences as a working person. “I was able to buy some much needed clothes and save a little money for college.” She saved about one hundred dollars and “with this money I had earned and $150.00 which I borrowed from Tommie and Maxey [two of her brothers], I started to college at Southern Illinois Normal University on September 16, 1946.”

As Mom’s diary account suggested, the Newell family faced money difficulties in the immediate post war era. Mother was the first girl after five brothers, and three of the brothers, Tommy, Maxey, and Dean, had served in the army and experienced combat. They returned home to Waltonville in 1945, living at home and picking up what work they could, jobs that family letters showed evaporated as quickly as they appeared. When not working outside the family, the Newell boys helped their father farm. The other siblings, Orval, the oldest brother; Faye; and our Mother lived at home too. With all these mouths to feed, Grandpa Newell had a rural mail route and painted houses in the area. Money, according to family letters, nevertheless remained scarce, especially after an outbreak of broken-down automobiles, farm machinery, and household appliances.

Our mother arrived at Carbondale in the fall of 1946 to find SIU a campus in partial chaos. The school newspaper, The Egyptian, noted that the coming of so many recent veterans on the GI Bill helped drive enrollment to an “all-time high.” In the same issue, one frustrated freshman student complained about the overcrowded and chaotic registration for classes that year. The article offers a powerful glimpse into the difficult time a rural freshman student like my mother would have endured.

Come Monday, September 16, a day not even the faculty will forget, let alone the 1500 freshmen who had to register for two full days. The old gym was packed with students, all freshmen, trying to locate proper classes. . . . After falling back in Parkinson Laboratory, you slowly worked your way in the general direction of the old gym for an hour or so. After reaching the door, some eager registrants found themselves ahead of schedule and were invited to work their way back again. Finally, gaining admittance to the old gym, you reported to your counselor and he signed about six of the required cards you had to fill out.

After standing in several lines to sign up for classes, our mother then had to return to her counselor and have everything okayed. The entire procedure made for a rugged start to the school year.

The student guide book given to each new student, Southern’s Style, a not particularly friendly thirty-three-page tome, suggested ways for freshman to navigate the SIU system. In one portion, female students were encouraged to make sure they had “saddle oxford shoes and socks, a raincoat, a dark dress, a pink silk dress or suit, and an evening dress for any special occasions.” A year’s expenses on fees and room and board was estimated at five hundred dollars.

Between the cost of clothes and the other expenses, mother had to find part-time work to make ends meet.

Despite these difficulties, Mom had her supporters. Her father wrote her often, telling her about the local happenings at home and around Waltonville and asking about what she was doing at school. In one letter, in response to a problem of which Mom complained, Grandpa Newell wrote, “Mary Alice, I know you will find a way to solve the problem. You always do.” Mrs. Genevieve Weaver, the Waltonville High School business teacher and a SIU graduate herself, sent Mother an encouraging letter just after Mom arrived on campus, attempting to boost Mom’s spirit while explaining the task they lay before her.

Dear Mary Alice,

This is just a note to let you know I’ve been thinking of you and wondering how things are going with you. I am so glad you are in school, for if anyone was ever made for success there, it would be you. College is a pleasant place to be—or so it seemed to me—even though there is lots of work to be done. You’ll soon feel quite at home at school, if you don’t already. The first 12 weeks are much the hardest of the whole four years.

Getting a decent room in Carbondale was difficult that year, and the student newspaper further warned students to beware of landlords trying to take advantage of students. Mother was fortunate, however, to be able to room with classmate Margret Sulcer and have two friends, Edna Holloway and Millard Kabat, from high school rooming nearby.

This pleasant circumstance soon changed, however.

Our Aunt Faye wrote in her first letter to our Mom, “We heard Edna [Holloway] had quit school and come home. We also heard Margaret [Sulcer] would have too if it hadn’t been for you. We heard you told her she just couldn’t quit, so Margaret stayed.” Perhaps speaking out of the second-born sister position, Faye added, “Poor Margaret, if she listens to you. She’ll become as handicapped as me I’m afraid.”

Mom’s insistence to her roommate failed to work. She reported in her diary how her friend “quit after the first week” and the other two Waltonville girls by the end of the first quarter term. She also wrote in her diary, “I like college life a lot, but I don’t like being away from home.”

The four Waltonville girls who had started out at SIU in the fall of 1946 stood as prime examples of the fact Look magazine had been wrong in its negative assessment of Waltonville High School. So, when Mrs. Weaver heard of the three Waltonville students leaving SIU, she quickly wrote our mother, Waltonville’s high IQ gal, another letter of support. “I was surprised that Mildred and Margaret dropped out,” she wrote then added a line that must have been like a hundred-pound weight being placed on our mother’s shoulders: The Waltonville community, Mrs. Weaver declared, was “is counting on you to do big things.”

A new roommate situation certainly added to Mom’s woes. She was forced to find other housing arrangements for the fall term and endured a less compatible roommate, a circumstance she elaborated on in her diary. “After my friends quit school. I was very lonely and living with this new girl whom I didn’t like. It made me very unhappy and home sick. But I believe the mood is sufficiently passed now.”

Mom did write in her diary about her successes in the classroom, successes that would have greatly added to the plus side of things, especially in terms of meeting the expectations of others. In a humble assessment, she wrote, “I was taking easy subjects the first term and for this reason, I didn’t have to study too much. The term ended December 6, 1946, and I came out with a 4.7 average.” Mom made A grades in zoology, English, and math, a B grade in music and a C grade in physical education. Given the jolt of such a new and difficult environment, she had certainly done well. Nevertheless, she was not completely happy with her grades. “I am determined to study harder next term. I’m taking chemistry, trigonometry, English, sociology and physical education.”

Mom returned home to Waltonville for Christmas break, the classes she’d signed up for in the next term already of worry. “I’m going to try and start in new and study harder,” she wrote in her diary, “I’m hoping my outlook will be brighter then.” Meanwhile, her time home was like visiting a warm soothing oasis.

I’ve been home almost two weeks now and my vacation will be up Sunday. Of course, I’ll be a little sorry to leave but I’ve had such a good time that I feel I could get back in earnest now. My parents were unusually low on money this Christmas and it looked as if this wasn’t going to be a very happy time, but as so many times, just being with family was enough.

In the winter term, because of increasing financial strains, Mom boarded with a wealthy Carbondale family. In exchange for her room and board, she cleaned the owners’ house, cared for their children, and cooked their meals, the work leaving less time for school studies. She wrote of being overworked and feeling shabby in her “worn dresses and slightly ragged winter coat.” One day the wife called Mom over and said, “I want to give you something.” She handed Mom her winter coat and said, “I’m getting a new one and thought you might like to have this.” Mom wrote, “I should have been happy to get it but, in fact, I felt humiliated.”

There were also, many years later, hints from Mom of harassment from the husband of the house.

As the winter term continued, Mom grew more depressed. She began to eat more than she should for comfort, “eating one piece of toasted bread heavily lathered with butter after another.” Meanwhile, letters to Mom from Grandma Newell told of unexpected expenses back home, such as cars that needed repairs and a breakdown of the washing machine. “It leaks all over the place and we can’t use it anymore.” In the same letter, Grandma Newell told Mom it was probably good she had not come home one weekend, as the family had “run out of cornmeal and bread and had biscuits three times that day.”

Mom’s younger sister, Faye, also wrote frequent letters, ones that gave detail about all the goings on back at home and in Waltonville. She often asked Mom if she was homesick and told her how much everyone missed her. Faye reported that Mrs. Weaver monitored how frequently Mom came home on weekends, checking for signs she might be homesick and might want to drop out of school. “Mrs. Weaver asked me Monday if you came home this weekend and I told her yes. Then she didn’t say anymore.”

The most difficult thing Mom faced in the second term at SIU was class work issues, perhaps brought on by her disturbing living conditions with the wealthy family she stayed with and worked for. She was performing poorly in chemistry and math (trig), the former class being essential to her vocational plans of becoming a science teacher like her beloved Mr. Kellett. When she revealed the situation to her family, her father quickly wrote back, telling her, “Don’t worry too much over low grade, etc. Probably all in a day’s work. I know you can take care of the situation anyway.”

Mom finally wrote Mrs. Weaver, telling her former teacher of her growing despair. Mrs. Weaver quickly wrote back. I suspect Mom’s old Waltonville teacher was pretty upset at the very thought of Mom dropping out of SIU.

Dear Mary Alice,

I was glad to hear from you, but sorry you were feeling blue. That feeling comes and goes with all of us in any kind of work, and by now I’m sure you are feeling a little better. I’ve shed many of tear over trig and chem—and French, but somehow things were never quite as bad as they seemed. I confess that to this day I don’t know much about trig or chemistry.

I understand you are working now. Hope you don’t have to work too hard. I wish you had a job on campus. Did you try for one? Sometimes students who work in private homes get a bad deal. What do you do?

Then came the horrible weight of expectations again: “We’re all counting on you, and I know you’ll come through just fine.”

Toward the end of the winter term, mom grew low on money but did not want to go to the family she boarded with and worked for to ask for a loan. Instead, she told her mother about the problem. Grandma Newell wrote back and said her brother Dean would loan her ten dollars. Uncle Dean’s letter to mom about the matter was a hoot.

Dear Mary Alice,

I don’t know how come Mom to say that I said I would send you $10.00 unless I’ve been talking in my sleep. By the way, I’m growing a tootsie, tootsie little mustache. Me and Maxey went rabbit hunting today and got 6 rabbits for the hound dogs. Well, I have been thinking it over. I might send you a $ten being Mom already said I would.

Yours Truly,

Dean Lloyd Newell

P. S.

The next time you need money you should put the mooch on brother Tom, for I’m fairly on the rocks.

At the end of the winter term in late March, Mom made a fateful decision. Just like the time she declared she wasn’t going back to Mt. Vernon High School after her junior year, Mom declared she was done with college. Many in the Waltonville community hoped Mom would just lay out for a while then return, but it was not to be.

The last thing I found in the lard can that held the forgotten material telling of our mother’s SIU adventures was Mom’s letter of application she wrote to the Mt. Vernon Register News in late March of 1947 for a secretary’s job. It was a narrative demonstrating great confidence, backed up by examples of her previous work. As it turned out, however, Mom got a job in Mt. Vernon as a secretary at Holman Ford Motor Company.

One day an older man and his son came into the car dealership, looking for a new car for the son. A Holman salesman moved quickly to try and get a deal. The son, in his mid-twenties, dark haired and handsome, looked so sad that Mom later asked the car salesman who he was and why he looked so despondent. “His name is Keith Mills and his wife recently passed away,” the salesman told my mother. “Poor guy. He has a little baby daughter to care for.”

Many of you know the rest of the story.