Funny how seemingly unrelated events can connect into undeniable cause-effect scenarios that when looked back upon, seem nothing less than providential. Such was the case with the only vacation my family ever took with the prime mover in this story of oddly connected occurrences being our father, Keith Mills.

Coming home from WWII, Dad took the handiest job available in the rural Horse Creek area of his birth, farming with our Grandfather Mills. After he married our mother, Mary Alice Newell, he purchased six sad-eyed Jersey cows that he milked and got cream from and raised chickens whose egg production, along with the cows’ cream, was used down at Leonard Wilson’s General Store to trade for groceries. All was not well, however, with our dad.

The arrival of spring and of the farming season was an exciting, uplifting time for many farmers, a call to the vocation they loved. For Dad, the spring brought only moodiness and despair. It wasn’t that he didn’t try; an article in the Mt. Vernon Register News in the summer of 1953 mentioned dad being selected by farmers in his township as one of seven farmers to serve on a county board dealing with Federal farm subsidies. Still, he was just not cut out to work in the fields. It probably didn’t help that my older brother, Marshall, and I came eleven months apart, followed two years after my birth by our youngest sister, Karen, leaving poor Dad going from the difficulty of a job he did not like during the day to a home after work that contained three needy rambunctious kids in diapers and an overwhelmed wife.

All this changed in 1953 when our then twenty-nine-year-old father began selling Ford cars for G. B. Holman in Mt. Vernon, Illinois.

The story of how Dad came to snag the car salesman job at Holman Motor Company is lost with the passing of time. To us siblings, it’s the primary job we remember Dad having. One thing’s for sure: G. B. Holman must have been stunned by Dad’s immediate success, telling his other salesmen, “That boy sure can sell cars.”

There was little secret to Dad’s selling achievements. He possessed a wonderful gift for gab with friends and strangers alike, having the rare ability of sincerely listening to whatever people had to say. I’d be willing to bet that some of his most steady customers over the years brought a car from Dad almost every year just for the therapy. It didn’t hurt either that Dad had a large network of family and community connections. It was a perfect combination for a car salesman.

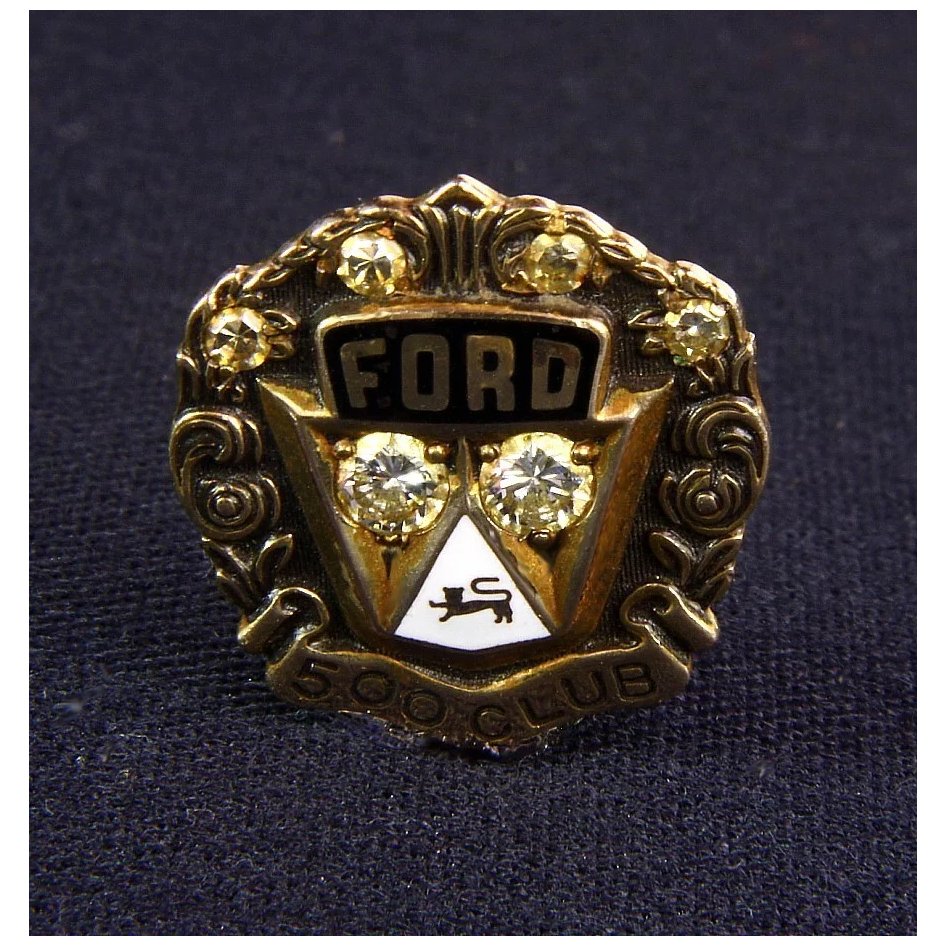

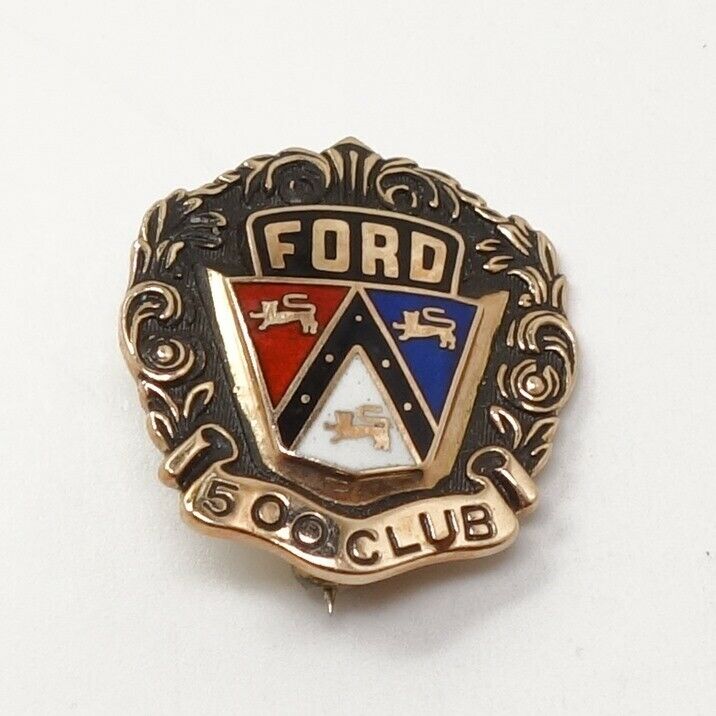

Dad’s natural skills soon parlayed into his receiving many prestigious Ford Five Hundred Club awards given every year by the Ford Motor Company to its very top salesmen in the nation. The award came with a certificate and an attractive 10K gold lapel pin. A few of the pins Dad won also contained clusters of small diamonds, and my older brother, Marshall, and I used to sneak them out of our Dad’s desk whenever we could and fastened them to our shirts like war medals, parading around the house until Mom caught us and made us put them back.

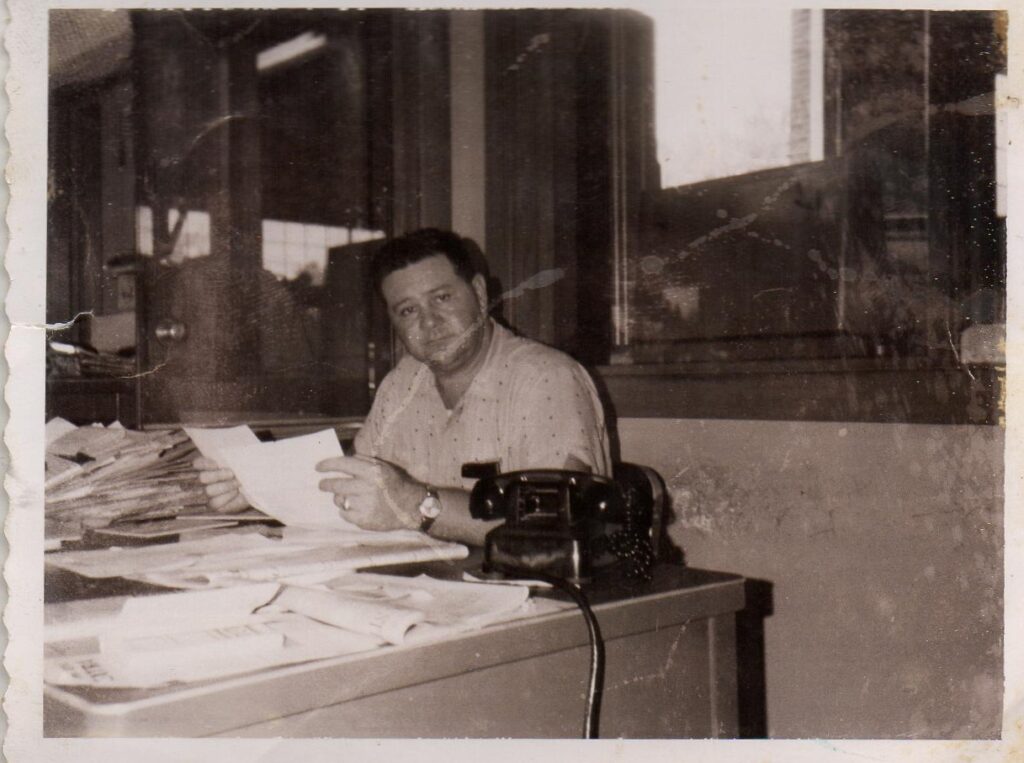

Like an artist who fashions intricate carvings out of castoff pieces of wood, there were always plenty of creative “wood chips” lying around from Dad’s car selling efforts. At his work desk at Holman’s, on our kitchen table, and on Dad’s scarred nightstand lay wrinkled-up pieces of scrap paper covered with the manic scribbles of calculations and hurried cross-outs, trade-in car deals with computations as unclear and mysterious to my young mind as hieroglyphics.

Poor Dad. The romance of selling cars eventually faded, leaving him swimming in the same boredom of his farming days. Dad’s vocational unhappiness was made worse by his friendship with several state troopers whom he talked with daily at the little sandwich shop across the alley from Holman’s. Dad was intrigued by how they looked in their uniforms, how they always stood for a second and cocked their hats when they got out of their cars to write a ticket. There was the telling too of dramatic car chases, bad guys being caught, and tragic car accidents. Less exciting, but just as important, were their accounts of their future pensions, the latter element absent in Dad’s car salesman occupation.

One day, as Dad and one of the troopers chewed at the dry roast beef sandwiches served at the little eatery, the trooper turned to my father and said, “Why don’t you apply to the academy, Keith?”

My brother and I listened to our parents talking about this one night through the thin walls of our house. It was a tricky situation, as our father was just one year under the cut-off age. But that wasn’t all. Dad had been heavy all his adult life, well over two hundred pounds. He’d have to move quickly in both his applying and in his getting into shape. He did so in 1958, an action that put into motion a set of unexpected events.

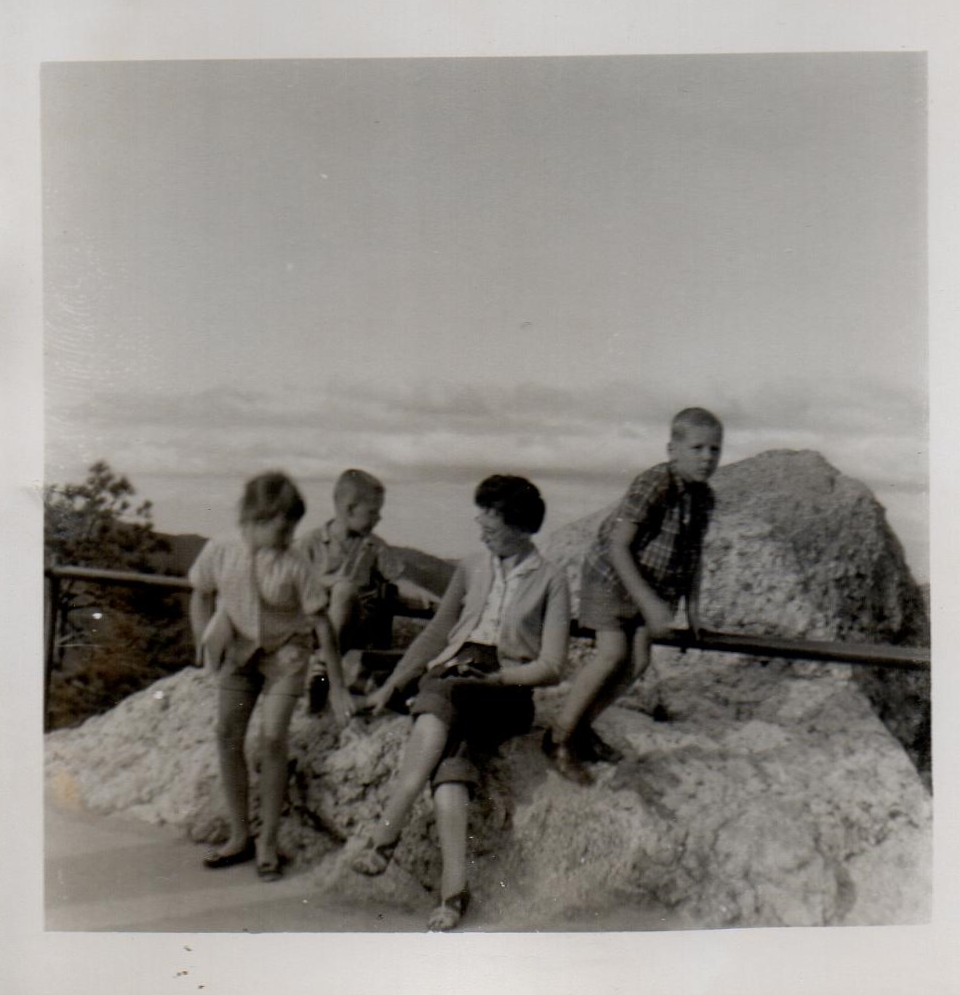

In the mid-summer of 1958, when I was six, our family went on our one and only vacation, what was supposed to be an epic three week trek out to the Grand Teton Mountains and beyond. The event was made more memorable by our father’s frenzied training regimen earlier that spring, before he went to the state capital at Springfield and to the Illinois State Police Academy to be tested for the state police.

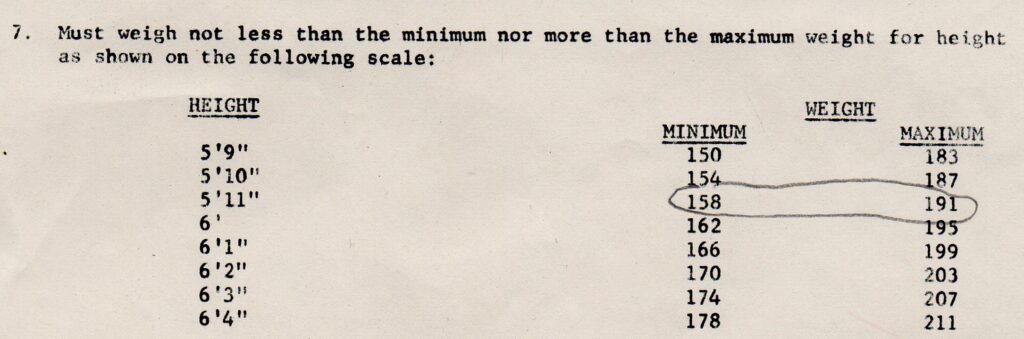

The center of Dad’s life while in training, and, by proximity, of ours, became an eight by eleven and one half piece of paper, page one of an official letter, Dad taped to our kitchen wall. He circled one part in pencil: height- 5’11’, maximum weight- 191.

After Dad left the room, Marshall and I pulled two chairs over to the wall to stand on and read the piece of paper several times, the paper explaining how the applicant would have to pass a physical training test, along with a written and oral test.

“So, Dad just has to lose some weight and get into shape,” Marshall said, knowing our dad’s strengths in communication. I shook my head in agreement. It did not occur to us to inquire about why our dad wanted to leave his car salesman job in the first place, or, more importantly, to ask about the impact the job change would have on the family—it said right on that piece of paper Dad taped to the kitchen wall that new state troopers were not allowed to serve in their home State Police district. But Marshall and I could not have been more excited about the whole affair than if Dad had declared he was quitting his job and becoming a sea pirate. We knew we’d be part of his getting into shape.

Marshall and I immersed ourselves in helping him in his training, sitting on Dad’s back when he did push-ups, holding down on his feet as he grunted out the number of each sit up, trotting along with him as he huffed and puffed up and down the gravel road that ran in front of our house. As we ran, Marshall and I imagined we were state troopers chasing bad guys, trying to keep up with our now trimmed-down father. Our two dogs joined in, barking and running in and out of the weeds on the sides of the road, flushing out criminals right and left.

It was an exciting time—Dad, like a boxer getting ready for the big title fight, giving it his all. It was the one time I remember Dad being trim.

Besides the thrill of helping our dad train, there was another side to the unexpected adventure. After the announcement of his upcoming academy try, our normally moody dad grew more fun and animated. He moved gracefully around the house with new purpose, as pound after pound of fat melted away, talking more to Mom, playfully rubbing Marshall’s and my burr haircut heads, calling our little red-headed sister, Karen, Carrot Top.

Dad even gave up his pipe and chewing on cigars, the better to get into tip-top shape, a decision our mother seemed very happy with.

On a subtle level, Dad’s new demeanor conveyed a heady sense of escape, of a delicious getaway from the boredom of selling cars, like the times when our two dogs would escape their woven-wire pen and run as hard and long as they could, dripping tongues hanging out the sides of their mouths, ears flapping in the wind, until we caught them and threw them back inside their pen.

In May of 1958, when Dad came back early from Springfield without explanation, the vacation I mentioned earlier was announced, leaving no time for us to ponder what went awry with Dad’s hope of becoming a state police officer. It simply wasn’t mentioned again in any formal way.

There was good reason for my family’s sudden fit of amnesia—the idea of such a grand vacation was so exotic and foreign to us that it absolutely swept away any other previous concerns like a massive landslide. It was an utterly unexpected and completely perfect Christmas present in the middle of the summer, the promise of seeing new and wondrous things. In our boring little self-contained world, such a promise was literally intoxicating, as well as a bit scary.

Another positive factor—and I can only speak for myself—we never went out to eat, McDonald’s having yet to appear on the scene and our dad being on the frugal side. “We’ve got bologna at home” was one of his common sayings. Eating out had a glamour to it then, something only the upper-class folks commonly did and not the common Horse Creek folks. The kind of grand vacation our father envisioned was guaranteed, at the very least, to provide the reality of new and interesting food in interesting eateries. This aspect was made more pronounced by the fact that Mom was often an indifferent cook, not one to make a complicated meal from scratch, except for special occasions like holidays or when we had the preacher and his family over for Sunday dinner. There were exceptions. Any time she sensed I was down about something, a large spaghetti meal appeared for supper, my favorite, or she’d surprise me by making me a thick cheeseburger, another favorite. As a small child, I always asked her to put the mustard on the cheese side, a request she found so endearing, I repeated it every time she fixed a cheeseburger for me.

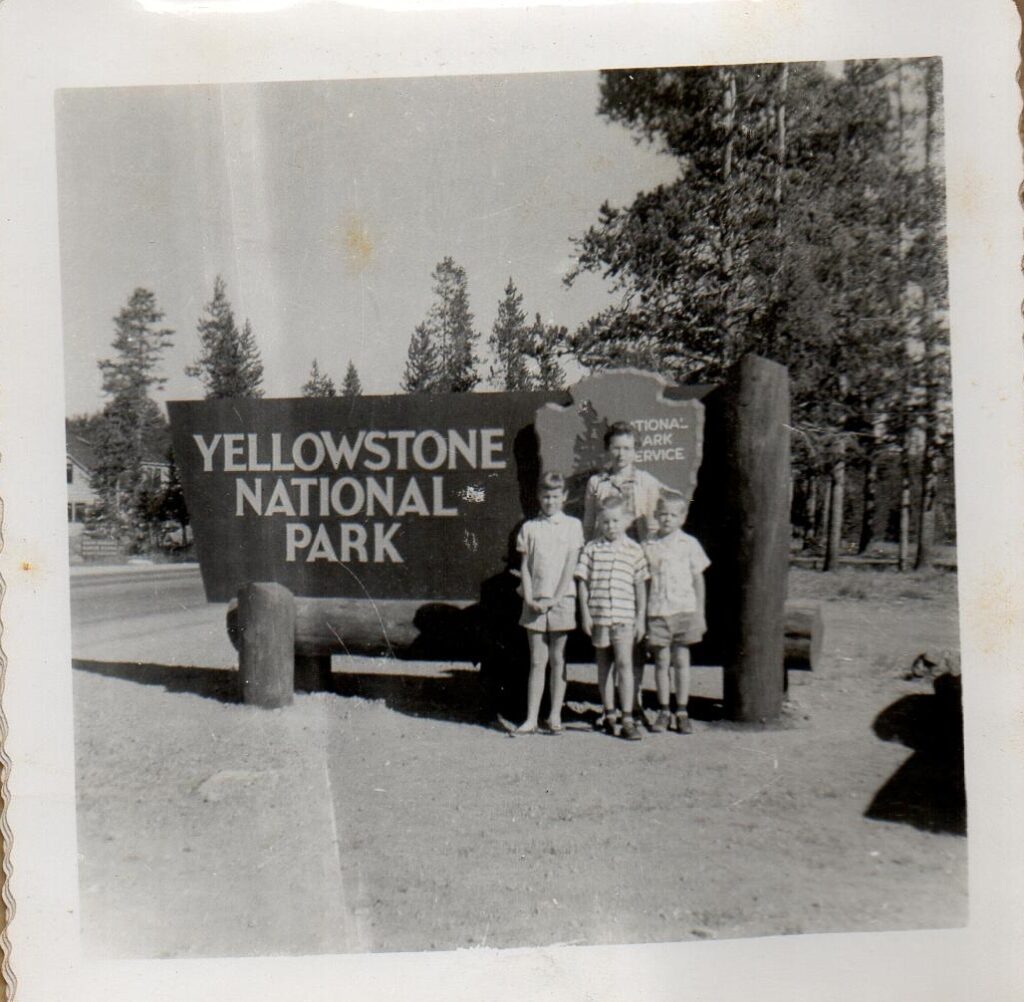

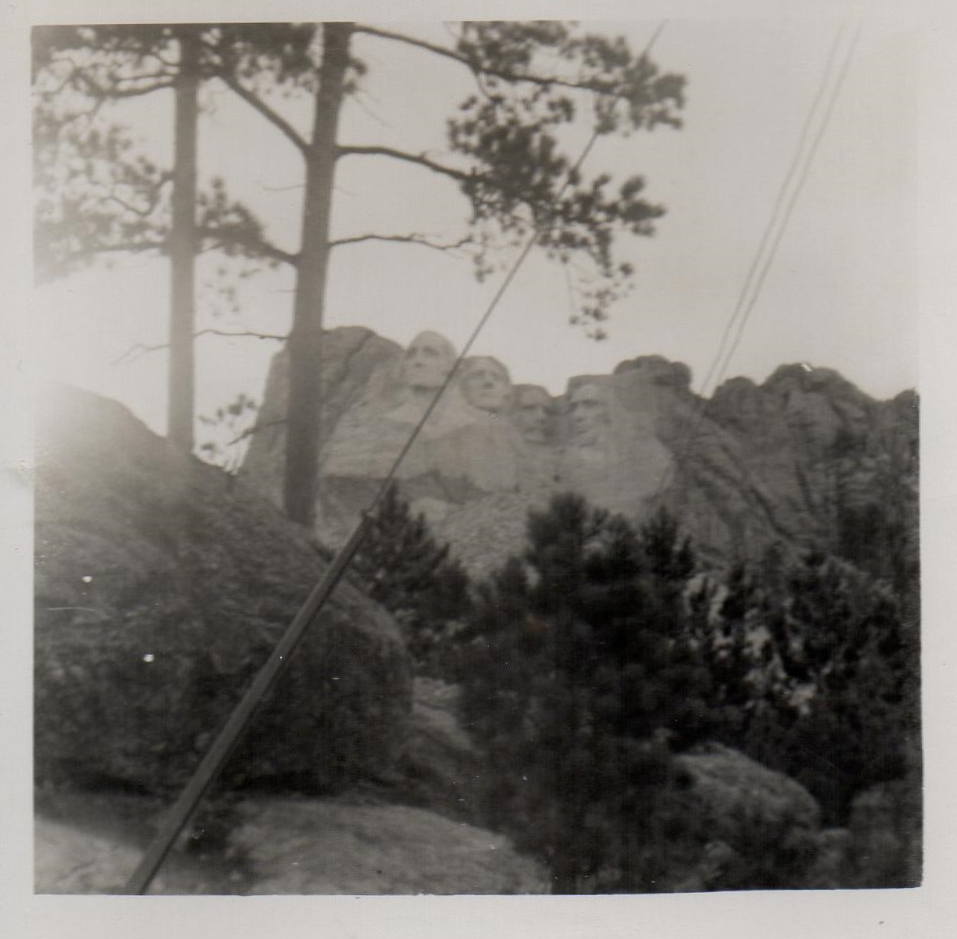

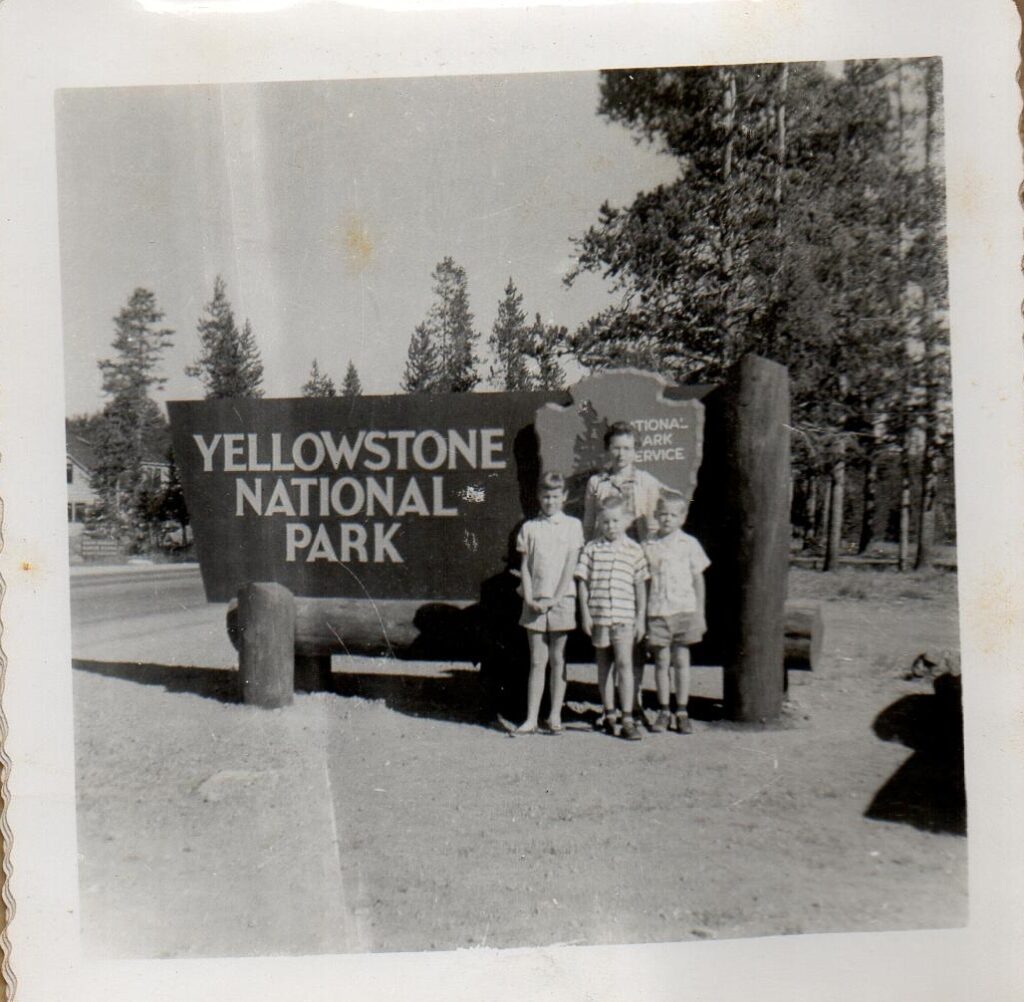

Photos abound of our epic vacation trip: of us walking hurriedly toward Mount Rushmore, our heads looking up, our eyes fixed upon the five forlorn and bored faces in the distance; of small groups of thin tombstones, worn and scattered across a weedy hillside at the Little Big Horn; of us standing, tiny and insignificant, in front of Old Faithful as it boomed, steaming and dancing in the background at Yellowstone Park; of Marshall and me in short sleeves on Pikes Peak, throwing snowballs.

Oddly, these photos bring back no memories for me of what occurred at the majestic places we visited. What I do remember about that trip were little things that fail to carry any weight concerning great lessons learned or even any sense of awe.

This is not to say that the entire affair wasn’t dramatic.

Two things happened a few days before we left. The first involved Marshall and I sneaking out to play in the demonstrator car from Holman Motor Company Dad drove back and forth to work. We usually knew better than to mess around in the car, as Dad kept it immaculately clean for show. But the excitement of the upcoming vacation made us giddy with excitement and foolhardy with adventure.

Dad caught us with me in the front seat, pretending to drive. I got boxed in one ear for our transgression; Marshall missed any physical punishment, our dad having spent his initial anger all on me.

It wasn’t much of a blow, more of a slight swat, but for some reason, it really hurt my feelings. Dad must have picked up on my being upset, as a look of shame came to his face.

Still, he did not say he was sorry.

Also, before we left, the problem about our little sister, Karen, going on such a long vacation was resolved. Our eleven-year-old half-sister, Sharon Rose, who lived with our grandparents, would go with us out west and Karen would stay with our Grandpa and Grandma Mills. Marshall and I figured Karen, who was four at the time, was too young to understand what the deal meant. When she finally did, we would be long gone, probably driving west of Peoria, looking for a place to stop and eat.

Just before we climbed into the car to leave for our grand vacation, Dad playfully snapped a picture of our Mom as she got into the car. Perhaps she knew the marathon that loomed ahead—her face having the look of grim determination.

The landscape grew treeless and as flat as our kitchen table as we drove northwest through Illinois and into Iowa. Crossing the Mississippi River brought some temporary relief from the boredom, as it signaled, in our minds anyway, that we were entering the West. Marshall and I looked at the windows with intense concentration, hoping to see a cowboy. All we saw, however, was corn, the same basic scenery of Illinois. The car was not air-conditioned, and the constant air, blowing like a gale through the rolled-down windows, along with the road noise as the car chewed up mile after weary mile, slowly wore us down, leaving us punch-drunk and irritable.

As the day rolled on, my brother and I begged Dad to stop at a gas station so we could get out and stretch our legs and go to a restroom. Our requests were ignored, Dad blowing us off with a grunt that meant no, until our Mom would finally say, “Now Keith.” What few restrooms stops we did take, one where we pulled off on a back road and peed into a ditch, were so short that Marshall and I would get a little pee each time on the front of our jeans, zipping up and running back to the car. The only “long stop” on that first day was a brief interval so Dad could get a photo of the family standing in front of a corn field that had the tallest corn we had ever seen.

Not that we kids were easy. There were no seat belts, so we squirmed around restlessly in the back seat, jockeying to stand behind and between our two parents, a spot where we could better hear what was going on in the front seat and catch a bit of the music playing on the radio, a sound that was otherwise drowned out in the back seat by the wind. Listening to our parents’ chatter, we also picked up bits and piece about what happened at the state police academy, the sting of the recent event apparently still burning inside Dad like poison. Dad had made the highest score on the written portion, done more than decent on the physical training test, and then was told he had flopped on the oral interview, an impossible occurrence I thought, given our Dad’s great salesman skills.

Our father lamented about his humiliation more than once after we reached Iowa, turning his head toward our mother as he drove west, wiping a few tears from his eyes. This may have been the first time we saw our Dad cry, but we kids had the attention span of squirrels, and our sympathy did not last long. War was brewing just behind where our parents sat and talked.

Unlike our younger sister, Karen, our half-sister, Sharon Rose, turned out to be one tough adversary there in that crowded backseat. She simply did not relent when we pestered her, giving back better than she got with quiet but painful pinches and hard shoves that shook the front seat where our parents sat. This surprising circumstance turned Marshall’s restlessness toward me, and at times we all but wrestled, flopping around and making plenty of racket.

Had I been paying attention, I would have noticed our Mom moving more and more toward her side of the car as our journey progressed, noticed Dad growing quieter, his head becoming as still as a statue as he stared straight ahead, glaring into a gathering dusk.

We stayed at a motel in Minnesota at the end of the first day of our journey, next to a lively drive-in restaurant where car hops, dressed in bright red outfits, zipped from car to car, taking orders, their long skirts flowing in their hurried wakes. The sun, a big red ball of well-being, was low on the western horizon. Eating at this drive-in would be the most memorable part of the trip for me.

We pulled into a slot and parked, and Dad rolled down his window to order. Normally, my brother and I would have been very rowdy in this circumstance, but the unusual coloring of the car hops, dark skinned teenage girls, caught our attention. As a pretty girl approached, her pen raised in one hand, an order pad in the other, Mom whispered to us in the back seat, “She’s an Indian.”

I had the coveted middle position in the back seat when the carhop brought out our orders, loaded up impossibly high on a tray that she attached to the partially rolled down window on Dad’s car door.

When I unwrapped my cheeseburger, I whined loudly in disappointment.

“There’s no mustard on mine!”

Dad’s response was quick as a cat’s and as explosive and traumatic as an unexpected booby trap going off. In one motion, he took his cheeseburger, removed one of the buns and rubbed the rest hard on the side of my face, causing the carhop to take two steps back.

“There’s your mustard,” he said.

The next day, before we left, Mom slipped off to a little one room gift shop next to the motel where we stayed and bought a thin green “Indian blanket.” After we kids got into the car, Mom opened the door on my side and tucked the blanket around me. “You guys are going to take turns using this special blanket, and Randy will go first.”

Not even my brother complained.

The leg of the trip from our first night’s stay to South Dakota was especially quiet in the back seat. Half-way there I developed stomach cramps and an awful case of gas, which I could not control. Dad finally pulled the car over to the side of a busy highway and walked to my side and opened the door. He took the blanket that Mom had wrapped around me and put it over my head, so that it covered my entire body.

“Now, the rest of us won’t have to suffer,” he said.

Through the blanket, I could hear Marshall laughing.

My last solid memory of our vacation was staying in a motel at Pueblo, Colorado. This would have been after our visits to Pike’s Peak, the Little Big Horn, Yellowstone Park, and Mt. Rushmore, and after my stomach problems abated. The plan was to drive all the next day down into New Mexico and stay with my Grandmother Mills’ sister and her family.

It must have been around the Fourth of July. Kids were lighting firecrackers outside our motel room, by the swimming pool, the random bursts followed by wild laugher and shouting. The motel floor was tile, in a Native American motif. As Sharon Rose took her shower in the next room, Marshall and I lay on the cool bedroom floor and tried to count all the different figures we imagined emerging from the designs—a dragon here, a giant bird there.

While Dad was taking his shower, a heavy thud came from the bathroom, followed by a holler and then by a curse. Mom ran to the bathroom, we kids right behind her.

Dad was on his back but seemed okay. He lay there, however, a bit stunned by the unexpected fall, finally getting up and covering himself with a towel. He went to where the beds were, rummaging through his and Mom’s suitcase, finding his pipe and lighting it up, having his first smoke since his state police training days.

His body relaxed more with each slow puff.

“That’s it,” he said. “We’re going home.”

Our youngest sister, Karen, had her own unique memories of her time while we were off traveling through the Wild West. Grandpa and Grandma Mills took her to a fish fry party of my grandparents’ generation down on the Ohio River, at Cave-in-Rock State Park. When she asked to have a cup of what everyone was drinking, she was told it was “soup for grownups,” and she was given a cup of water that tasted fishier than our well water back home. Poor Karen was also taken by our Grandmother to her first funeral visitation, that of a cousin of Grandma’s named George Pierce. No one explained to four-year-old Karen the context of a funeral home visitation, just carried her in and sat her down on the front row, right in front of the casket, leaving her to ask aloud in the otherwise quiet room of mourners, “Why is that man in a suitcase, Grandma?”

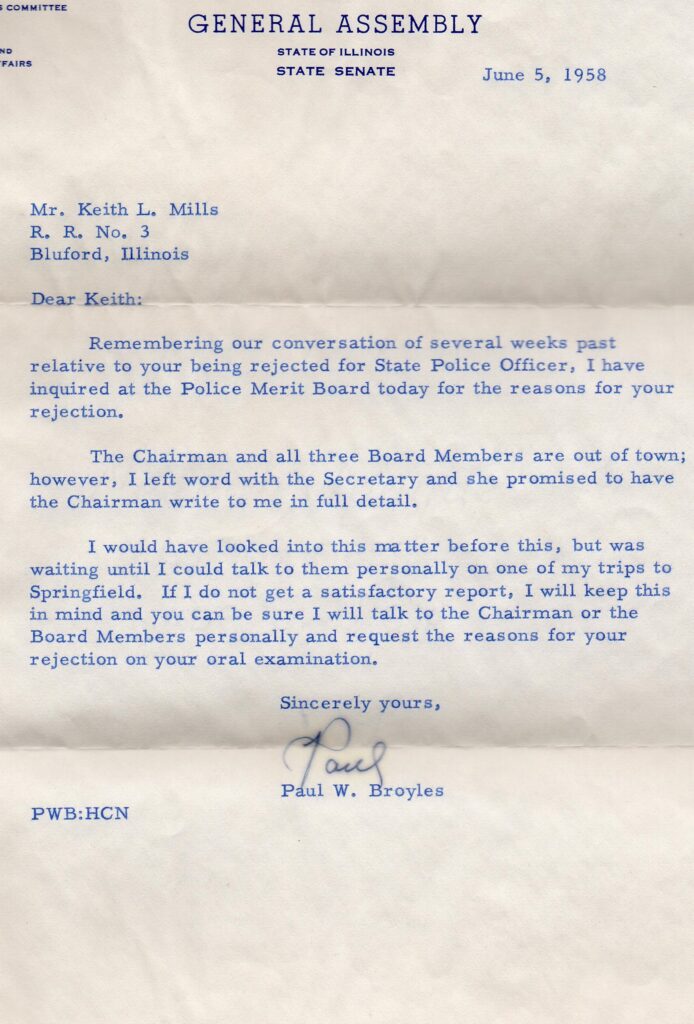

Once home from the vacation, Dad was gloomier than ever. He went back to his old eating habits, regaining much of his weight, dreading having to try and explain to his state trooper acquaintances what happened. Meanwhile, his working back at Holman Motor Company brought him little joy. He contacted a political friend of the family, state senator Paul Broyles, an infamous anti-communist warrior from the late 40s and early 50s to inquire as to why he was not selected into the state police academy. Senator Broyles wrote a letter addressed to “Dear Keith,” and signed “Paul” promising an investigation and swift justice.

Senator Broyles eventually got back to Dad with two bits of news. Apparently, someone, and Dad thought this to be G. B. Holman, used their influence to get Dad turned down. G. B. Holman certainly had the political influence to approach the State Police Merit Board and may have done so in hopes of keeping Dad on as a car salesman. After all, there weren’t that many Ford 500 salesmen around. It would certainly explain Dad’s failure on the subjective oral test. The good news was that Broyles had used his powerful influence to get the merit board to allow Dad to reapply. Dad, however, was too near the cut-off age and too discouraged to try again.

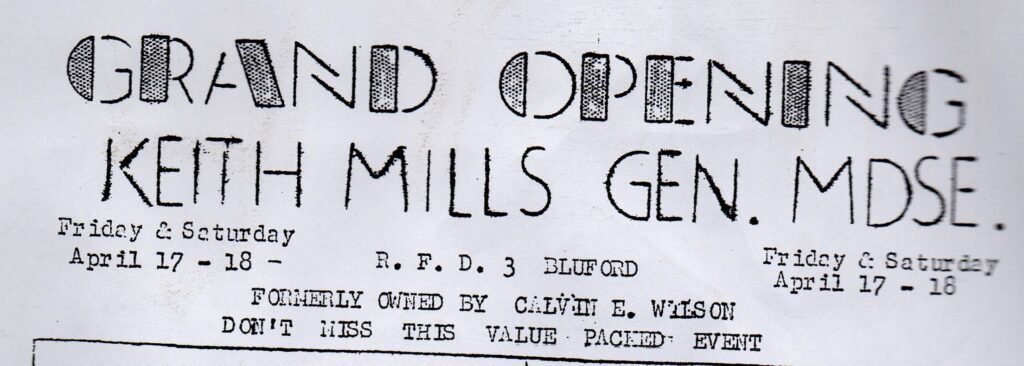

Dad’s response to his suspicions about G. B. Holman’s possible role in his failing to become a state trooper was to quit selling cars and go into the country store business, buying an old prior store building down on Horse Creek. The endeavor lasted only a few months before he and G. B. made peace. Dad was made sales manager and worked at Holman’s until 1969, when he then went to work for the Illinois Department of Transportation, a job that had a nice pension waiting at its end. He was an inspector for the IDOT when he passed away on the job on January 30, 1978, during the brutal and epic blizzard that year.

There is one last memory I have of our family’s only vacation. When we got to Potter’s Corner coming home, a few miles from our house, Dad pulled the car over and told me to come up to the front seat. He let me sit on his lap and I drove the rest of the way home, our mother squirming in her seat as I happily went from side-to-side on the road, dad paying me back for boxing my ear on the eve of our epic trip.

Marshall was green with envy, but it was a fine and just ending to our family’s one and only vacation, as far as I was concerned.