My father’s people immersed themselves in local political affairs with the same fervor they showed when they were baptized in the murky waters of Horse Creek in southern Illinois. Ancestor Barney Wells, Farrington Township’s first white male settler in the late 1830s, was a zealous Jacksonian Democrat, keeping a forty-gallon keg of whiskey on his front porch around election time, a practice that helped him gain the office of Justice of the Peace in the Horse Creek voting district, later Farrington Township in Jefferson County.

Allegiance to the Democratic Party would not last in my family. Both great-great grandfather Jack Pierce and his son Charlie held Farrington township offices as Republicans. Charlie Pierce, who carried great sway with the people in the township, was a close friend to Illinois governor Louis Emmerson in the 1920s, traveling to the county seat in Mt. Vernon to dine with the governor at the Emmerson Hotel, eating buckets of raw oysters nestled in ice and giant heaps of ice cream. Charlie also found that holding a political office was not for the fainthearted, once receiving a threatening anonymous letter complaining how he and the Pierce clan “think they run this place.”

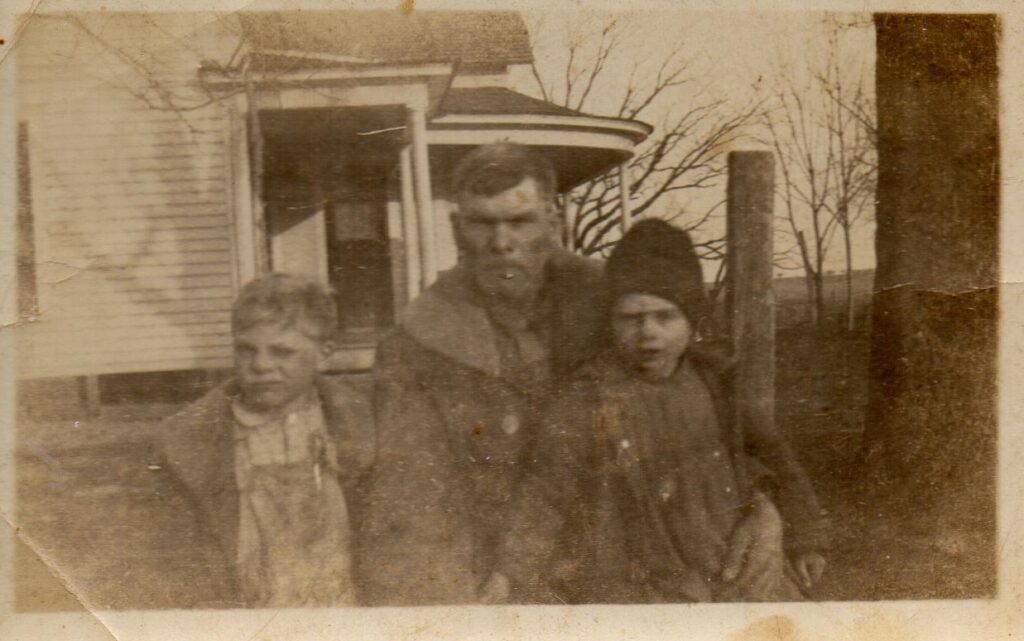

There was other evidence of my family’s historic political bent. On Grandmother Mills’ dresser sat a framed photograph, a picture taken of my twelve-year-old father and his younger brother, Curtis, both dressed in white linen suits for Sunday church. On my father’s lapel was pinned the largest political campaign button I have ever seen—a portrait of Franklin Roosevelt’s 1936 Republican foe, Republican Kansas Governor Alf Landon, his face in the middle of a sunflower.

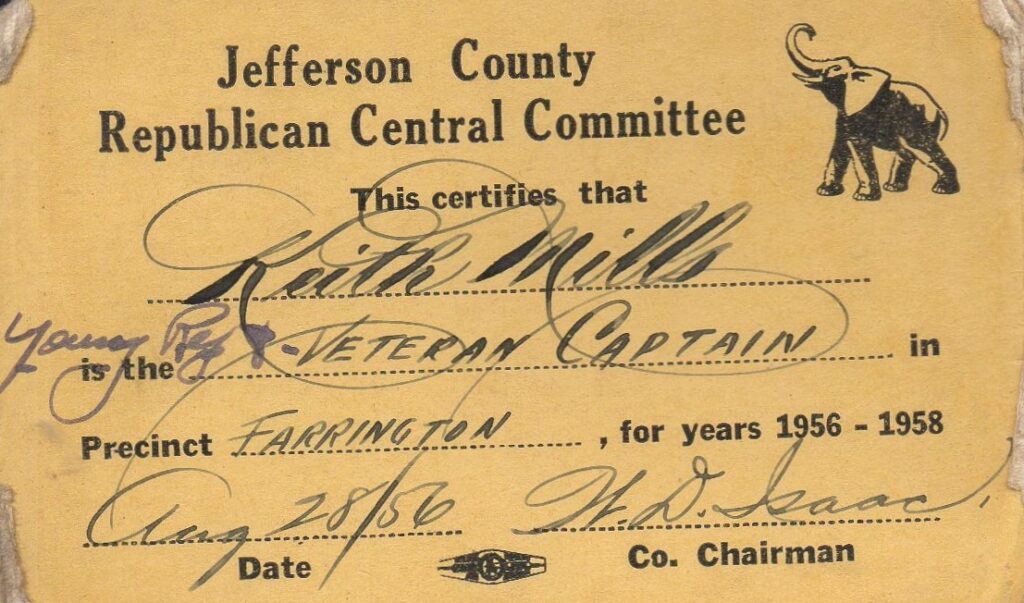

My father, Keith Mills, inherited the family political gene, holding office as a township supervisor and as a Jefferson County Board member for many years. In the early 1960s, starting when I was nine, there were monthly smoke-filled meetings of men at our house, talking politics, laughing, and shortening their lives inhaling great gobs of smoke. The meetings always deteriorated into a seemingly endless game of pinochle, during which I often fell asleep on the couch, but not before crawling beneath the kitchen table to count the holes in the red-heeled monkey-socked feet of my father’s political cronies.

One of my most tender memories of my father is of his gently carrying me, limp, half awake, from the couch to my bed after the visiting men had left.

As I got a bit older, I began to sense the excitement and seeming importance of the local, state, and nation political scenes, as exciting during election time as the Illinois high school state basketball tournament, and approached in much the same way, my family hovering around the radio and television on election night and eating popcorn, cheering on our side. It did not take me long to see also that election season was not about a political conversation, it was a contest—about winning at all cost.

I started reading the newspapers with a new eye, noting the shifting polls in national political races, and wondering who might win and why. It was also about this time that I asked for and received an explanation from my father, his understanding of the political landscape, his serious tone informing me that his understanding should be mine.

Good folks, wise Americans, were Republicans, Dad declared. Democrats were soft on Communism, misinformed, and even slightly dangerous, as if they carried a strange disease that might be catching.

When I asked him for details about the communist part, Dad just grunted.

End of conversation.

About this time, I went with my father to the county courthouse in Mt. Vernon, where almost all the elected officials at that time were Democrats. I caught a glimpse of one secretary, who I assumed was a Democrat as well, a woman whom my mother would have probably called a floozy, her face, showing makeup, her hair done up, smoking as she typed. When the Democratic Jefferson County sheriff came to our little grade school to electioneer at the annual Fall Fish Fry during my third-grade year, his pockmarked face and bull-like neck, the big oily pistol holstered on his hip, only reinforced my growing view of Democrats: they were scary, and, surprisingly, also mysterious and intriguing, much like the Catholic girls my mom said I should never date.

I did eventually find an interesting clue to Father’s interest in politics, a letter shoved down in a box at the back of Dad’s closet. The correspondence was addressed to “Dear Keith” and came from a local neighbor, Roy Holloway, a very kind older man who was a deacon in the Wells Chapel General Baptist church. The letter was dated February of 1954. This was a time when my parents basically had three kids in diapers, one a newborn, and Dad was struggling with his vocational calling. Farming simply did not suit his skills. Dad was also apparently experiencing a spiritual crisis, having stopped going to church. These were two not uncommon crises for a thirty-year-old male. The Roy Holloway letter, in part, certainly suggested a spiritual predicament in my dad’s life.

We miss you very much at church. I don’t know why you have quit coming as we have had some wonderful talks about the Lord and his blessings in the past. . . . I don’t mean to condemn or preach to you, but I love you too much to let you go without a struggle. I am sure you do not enjoy yourself as much as you do when you attend church and Sunday School. Well, this is the first time I have wrote a letter in years and know I have made a few mistakes. Maybe you will read this, and I hope I have not said anything to offend you so I will close with love to you and your family.

Your brother in Christ

Roy Holloway.

Dad resolved his vocational struggle in 1954 by becoming a full-time car salesman at Holman Ford Motor Company in Mt. Vernon, a job that was a great fit for his skills, as it involved working with people. His spiritual issues were probably a bit more complicated. He did return to church after receiving the letter from Roy Holloway, becoming a deacon and song leader, but I think it is interesting that also that same year he ran for a spot on the Jefferson County School Board and won his first political office. Perhaps being a public servant, helping the community to solve real problems, and the recognition that came with these efforts fed his spiritual needs as well and made him feel good about himself.

Not that there wasn’t a shady side to seeking a political office.

****

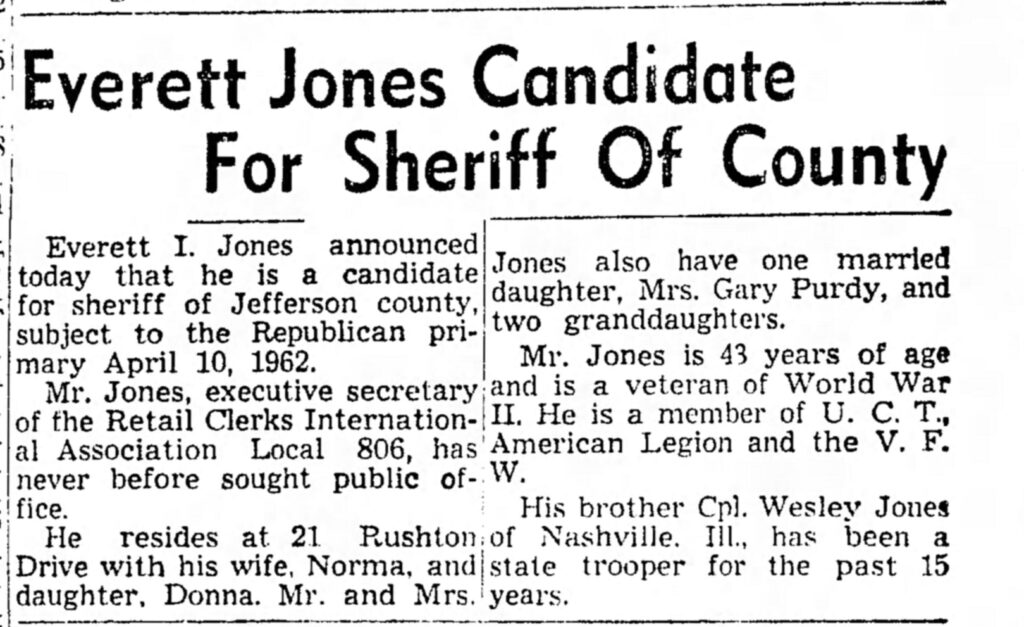

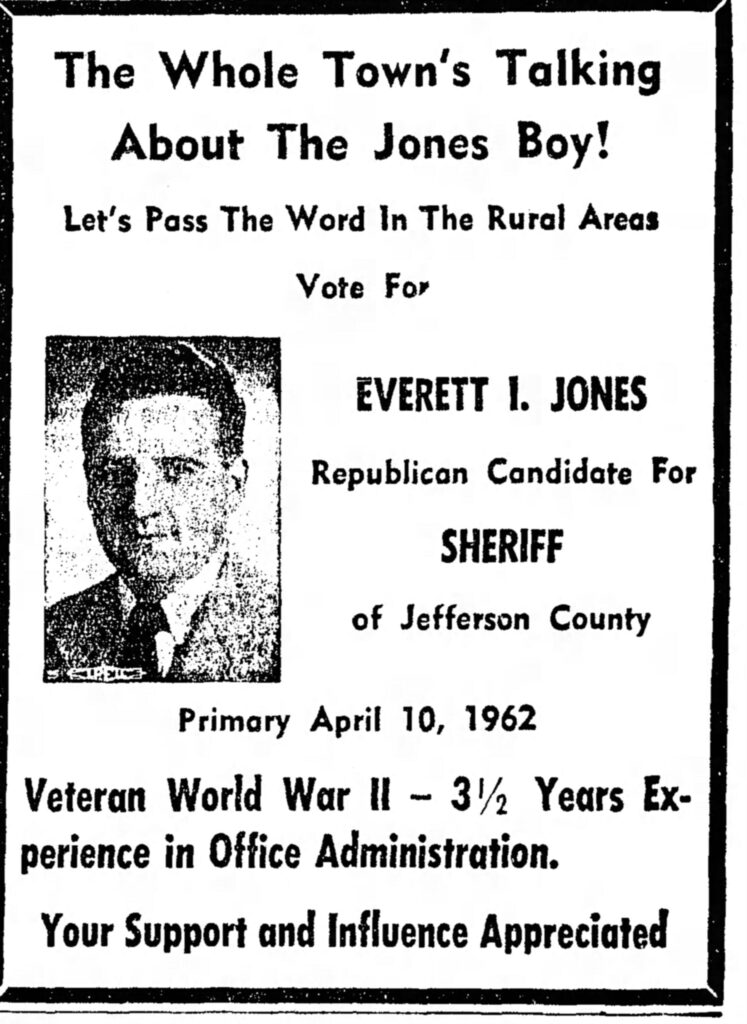

In the spring of 1962, my father worked on a political campaign in the primary season to help elect a businessman from Mount Vernon, Everett I. Jones, to the office of sheriff of Jefferson County. I imagine the two had met over a car deal at Holman Motors where Dad worked. Jones was a dapper-looking forty-five-year-old fellow with silver, wavy hair, always dressed in a three-piece business suit and highly polished black wing-tip shoes. Dad met with him on Saturdays in Mt. Vernon, and sometimes my brother Marshall and I went along.

Jones smoked incessantly, a common practice back then and one that left our clothes and hair reeking with the sharp smell of cigarette smoke, a circumstance of which our mother loudly complained. Mom was, in fact, upset when Dad first told her about his involvement in the upcoming election, worrying her wedding ring, knowing his tendencies to get worked up and excited. Dad must have caught her concern.

“My job is to help Everett get the rural votes,” he explained to our mother.

Mom was wise enough to let it go.

For my brother and I, the situation became an adventure, easing the awful boredom of our late winter rural world. I have a hodge-podge of memories of Marshall and I going into Mount Vernon with our father to Jones’s office, picking up political campaign signs to put out later and listening to the two men plot thrilling campaign strategy, as if they were planning how they might win a desperate war. Dad was optimistic that a strong block of voters from our Horse Creek area and other rural portions of the county would enable a first-time novice candidate such as Jones to win.

It sounded so much better in Jones’ office than when Dad explained it later to our mother—Dad setting up to be the linchpin in the surprise victory.

During these visits, Everett I. Jones would sometimes pause in his and Dad’s exciting but tense conversations and say something to Marshall and me, acknowledging us with some benign question such as “How are you boys doing?” or “Caught any fish lately?”

While his breath smelled of cigarettes, his brief inquiries were like being noticed by a god, leaving my brother and I in the glow of unexpected grace. I could see why our dad was so charmed by him.

Dad, Marshall, and I spent several Saturday and Sunday afternoons nailing up the campaign signs to trees and telephone poles in the rural Horse Creek District, moving a few of them later, as our father reevaluated their placements, trying to maximize their effectiveness. Once, in the waning twilight of a Sunday evening, our father had us jump into the car and travel with him a few miles down the road from our house.

He sat stiffly in the car seat, not saying a word. His tension was contagious. Both Marshall and I were as alert as two novice soldiers on our first patrol.

Dad stopped the car near a junction in the road and told us to get out of the car. Dusk had melted into a deeper shade of darkness. Stars were breaking out and the air was turning colder.

“Go to the corner and tear down all the signs but ours,” Dad said. This would be the only time our Dad would ever encourage us to plunder. We crawled like commandos, getting our clothes covered in cold mud. It was one of the most exhilarating events of my life.

Another exciting part of the campaign had to do with seeing my dad’s voice in the election efforts. One ad in the Mt. Vernon Register News declared,

The Whole Town’s Talking about the Jones Boy! THE JONES BOY FOR SHERIFF!

This was followed by a list of statements titled, “proven,” each explaining why Everett I. Jones should be elected sheriff. Another ad introduced Dad’s main strategy, declaring,

Let’s Pass The Word In The Rural Areas. Vote For EVERETT I. JONES.

Two weeks before the election, Marshall dropped out of going to town on Saturdays with our father to work on the campaign. I had grown tired too, but did not want to disappoint our father, who seemed jolly for a change, rejuvenated by the upcoming election.

On the last visit there, just before the Tuesday primary, I noticed for the first time how oily Everett I. Jones’s hair was and that his teeth and fingernails were yellowed by nicotine, how the vest of his suit was dotted by cigarette burns, like tiny bullet holes.

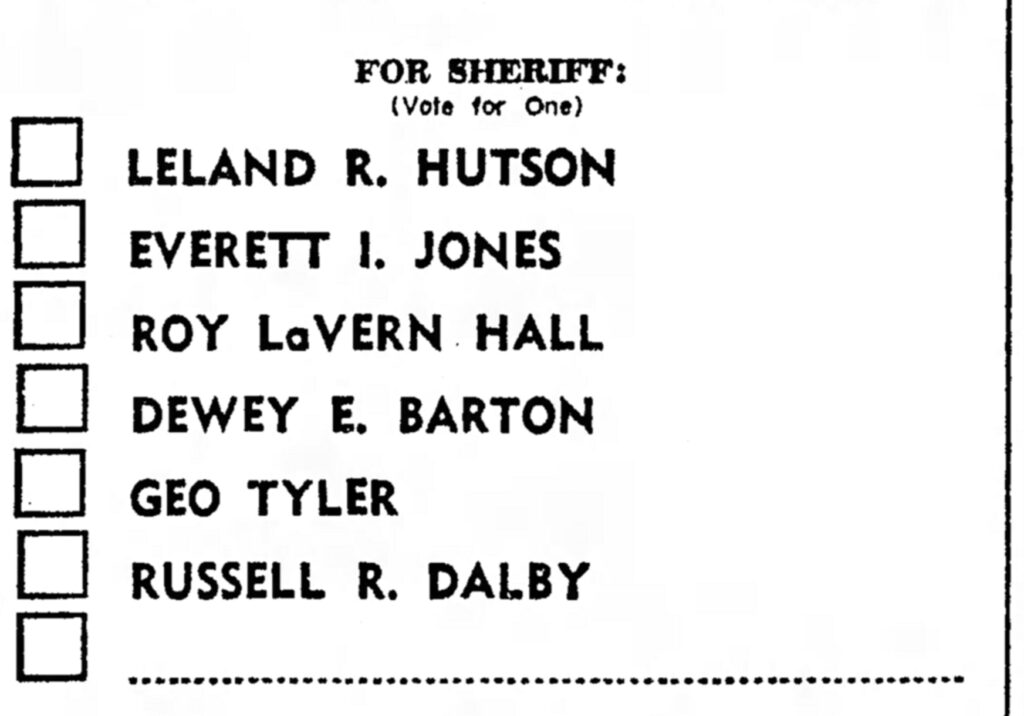

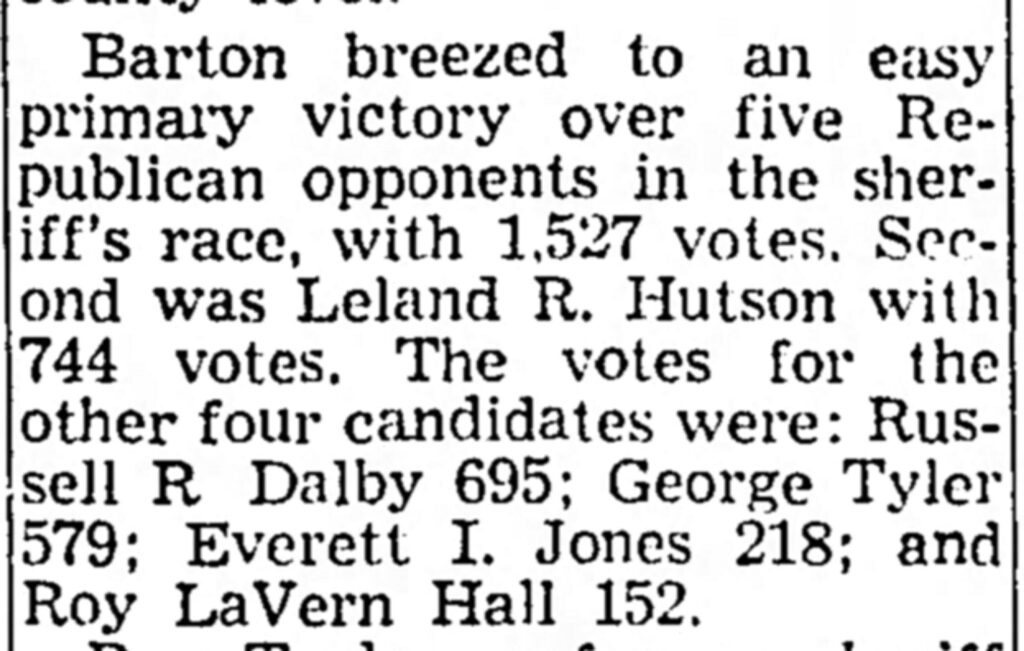

My family huddled around the radio on Election Night, bubbling with excitement, each of us with our own bowl of popcorn Mom had made. An hour after the polls closed, we knew Everett I. Jones had lost, coming in a distant fifth out of the six candidates. Out of 3,915 votes, Jones received 218. Farrington Township gave him 8 votes.

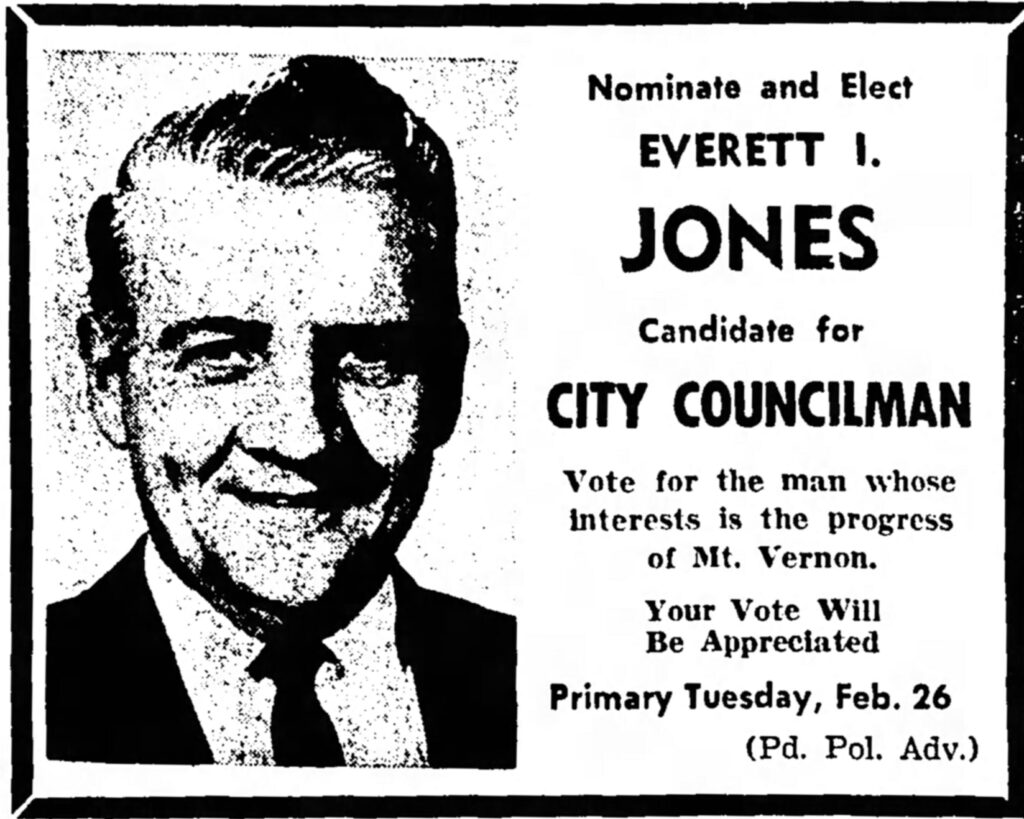

We did not take down the political signs we had so confidently put up, letting the rain, the wind, and the sun, along with township road workers, take care of them. A few of the signs placed on the farthest back roads withstood the elements and were missed by the road crews, reminders for a couple of years, when I biked past them, of my first involvement in a lost cause, the first of many to come. As for Jones, he would continue to run for local offices, for Mt. Vernon city councilman, for example, and with the same results as his try for sheriff. He finally found his political niche in the local Retail Clerks Union, holding the elected position of council president and presiding over 10,000 workers.

In 1963, the year after the Everett I. Jones debacle, Dad ran for Farrington Township supervisor, which also brought a county board seat position with it. My father was one of only two Republicans elected out of the thirteen county board members that year, and this marked the beginning of his long career in this post.

My father’s political public service came under my sour inspection when I went off to college in the late summer of 1969, about the time Woodstock was occurring. It was also the year Dad began working as an inspector for the Illinois Department of Transportation. Coming home for Thanksgiving that fall, I made the mistake at the family celebration of talking about how much I’d come to admire Franklin Roosevelt and his New Deal, an opinion shaped by one of my history professors. Grandma Mills lit into me right there at the dinner table, declaring she did not think much of that particular “Damacrat.” Grandpa Mills pulled me aside later and told me, in a low voice, “He did give us work,” the second and last political comment he ever made to me.

After the Thanksgiving incident, in the spring of my college freshman year, I took a state and local government class taught by a tough, no nonsense professor named Hasselbrink. Students had to attend at least one local government public meeting and write up a report as a part of their grade. I told the teacher of my plans to attend one of my Father’s county board meetings and was surprised when Professor Hasselbrink made the comment, “That should be an interesting event.”

I did not share my professor’s enthusiasm. It was the end of the sixties, and I had quickly become politicized at college along generational lines, doubting the wisdom of my elders, regardless of political party affiliation, seeing their generation as being unable to stop kids my age from dying in Vietnam and to fix the problem of racial inequality. Despite my judgments, I realized that going to one of Dad’s county board meetings was a handy opportunity to get a class assignment out of the way. I still went expecting to be bored and made a bit angry at the older generation’s old fashioned and likely prejudiced ways of doing things.

I ended up at the back of the county council board room at the courthouse, sitting on a scarred unpadded church pew that was like trying to rest on a rock. The board members sat around several long narrow tables placed to create a rectangle with a space left in the middle. Before the meeting, there was a constant low hum of talking, not unlike a hive of bees, punctuated by an occasion snort of laughter. A growing cloud of cigarette smoke clung to the ceiling, slowly descending as the meeting wore on.

The business session was more interesting than I expected, heated discussions blazing up a few times like a grass fire almost extinguished but brought back to life by a puff of wind. Several times my father whispered to one of his immediate neighbors, the two men’s heads almost touching. It was one of these moments that I became aware of a little bit of gray in my father’s hairline, of his use of reading glasses, of his looking vulnerable.

After the meeting, several of the members hung around, continuing to talk to one another, drinking the left-over coffee and enjoying the company. There was no sense of politics, of political parties, only inquiries about a family member’s health or a funny little story told well. I realized that all the men, like my dad, were WWII veterans, members of the greatest generation, a generation that lived through two great national emergencies and had worked together to survive. I knew too that these men were imperfect, but that night I witnessed them doing the best they could to solve the problems of our community.

I went back to college the next day, back to my sparse cold dorm room, shut the door and worked several hours on the report for Professor Hasselbrink. When I handed it in, Hasselbrink gave me a quizzical look when I held on to the stapled together pages a split second too long, unsure of what he would make of this quirky story.

In 1974, Dad was forced to run in a newly designed larger district, running against several other candidates instead of a single foe. The new district also placed him seeking votes from many new constituents. One of his challengers was a former mayor of Mt. Vernon, Joe Martin, a very powerful politician This would be Dad’s closest contest, with his winning after a recount. The next day’s Mt. Vernon Register News carried the headline Democrats Score Landslide Victory in Jefferson County. Keith Mills is Lone Republican Winner. It was the high point of my dad’s political career. He would die while working for the Illinois Department of Transportation four years later during the 1978 blizzard, serving the people of Illinois.

****

One last memory is connected to the Everett I. Jones sheriff campaign, a recollection that has stayed with me down through the years, informing my own political beliefs. The Sunday after the election, at Wells Chapel Church, one of the church members stopped my Grandfather Mills and gave him a hard time about our Dad’s work on behalf of Everett I. Jones. This was outside the building, next to the east side of the church.

Grandpa must have seen me in a sideways glance, my listening in on the heated conversation. After telling the prying man what for, he came straight over to where I stood. When he drew next to me, I caught a whiff of the sweet smell of crewing tobacco on his breath.

Grandpa was usually a quiet, gentle person, so it surprised me when he had gotten angry at the man, and now, that he poked softly at my chest, as if he were trying to drill the words deep into my heart.

“Remember this,” he said. “Your religion and your politics are your own business.” It remains one of the southern Illinois mantras I have taken along with me in my life’s journey.

And by the way, I received an A- on the paper assignment.