Like the adult southern Illinois farmers who lived around us in the late 1950s, my older brother, Marshall, and I did not have idle hands. He was eight and I was seven, for example, when we began constructing an elaborate system of paths through the mosquito infested woods that bordered the east and south sides of our rural farmhouse. Surely, no farmer worked as hard or with as much purpose as we did at making those trails. The floor of the woods was a thick, spongy carpet of leaves. At least a hundred years of compost. Like archaeologists removing strata, we used rakes and shovels and hoes to carve a narrow pathway through the deep layers of leaves, and, in the process, uncovered rippling balls of earthworms and stirred up the deep funky smell of moldy leaves.

Our little sister, Karen, traveled back and forth from our family kitchen, bringing us paper cups and Kool-Aid in a Mason jar. She also performed less tangible duties- admiring our work and keeping us company.

The first path we made did not run in a straight line. Instead, it looped and meandered around heavy brush and around massive trees whose heights and foliage effectively kept out much of the sunlight in the summer months. Forging trails in this gloomy atmosphere, sweating and panting beneath the trees’ high canopy, was like laboring inside a dark massive cathedral. There was little chatter among us as we worked. Marshall attacked the thick leaf cover and troublesome roots with practical gusto, driven by the sheer challenge and fun of it. Loving history, I brought a different motivation to the job, imagining that we siblings were like our pioneer ancestors before us, driven by some invisible force to go about taming the land. I also imagined a couple of the original inhabitants lurking nearby, hiding behind the trees with tomahawks and drawn bows.

There was another challenge besides road making. A narrow sandy waterway bisected the woods, causing Marshall to announce to me one morning as we walked into our woods, “We’ve got to have a bridge, Doc.”

Of the two of us, Marshall was typically the inventive one, he being the one, for example, who had given me the nickname of Doc. He directed me to several thick fallen tree limbs that were scattered off in different directions. We chose the three largest ones and dragged them to the stream, wrestling them into place so that they served as crude wobbly planks. The result, however, was more of a barrier than a bridge. We slipped and fell almost every time we tried to cross our creation, poor Karen falling and skinning both knees. We finally pulled the cumbersome limbs away and leaned up against a tree, exhausted and defeated.

It was I who suggested a solution, pointing out that we could use a large wooden door that had been torn off our one-car garage in a windstorm. Marshall did not think we could drag the heavy door that far into the woods, but I insisted we try. When we arrived at the water’s edge, all but spent, we somehow managed to lift the door and then flip it over. It landed perfectly, straddling the stagnant stream.

We ran back-and-forth across our new bridge several times, once jumping up and down on the door as hard as we could, testing its durability. It passed every test. No pioneer ancestor could have felt more accomplished. Karen lifted an empty paper cup in a salute. Marshall seemed less excited, turning my way and saying, “Tomorrow, we’ll start on another trail.”

Before we left the scene of our success, I walked to the middle of the bridge and gave it one last satisfying jump, enjoying the thin rising cloud of dust and the drum-like thud my landing made.

My siblings and I all but lived in our woods that summer, constantly swatting at the clouds of mosquitoes that surely gave thanks to their insect gods for sending us their way. We pulled ticks off by the dozens but were too happy in our woodland play to let these bothersome creatures chase us indoors. We only came back to the house for lunch, then quickly returned to the partial gloom of our woods, carrying our half-eaten peanut butter and jelly sandwiches with us. We worked and played and explored until twilight, until we heard Mom’s voice from a distance, breaking into our imaginary world, calling us to supper. We would reluctantly submit, carrying our tools across our tired shoulders like weary soldiers, trudging home in the gathering dusk.

Behind us, in the darkening woods, the manic call of a whip-poor-will announced the coming of the night as it heralded our leaving.

In the heart of the summer we carried big ripe tomatoes from Mom’s garden to the woods and ate them like apples, leaning our heads forward as much as possible to keep the juices from running down our chins, wiping any excess off on our forearms. There was only one inconvenience to our little Eden—it was hot and stuffy there, like a hot house, with little breeze because of the dense foliage. This only grew worse as we entered the dog days of summer.

“We’re sweating like pigs, Doc,” Marshall announced one especially muggy afternoon.

“But we’re happy pigs,” I replied.

After school started, we went into our woods only on the weekends. By mid-October, enough leaves had fallen to cover the paths we had made, and we gave up trying to keep the paths clear. We still walked the trails though, talking in low reverent whispers as we moved beneath the autumn foliage, falling leaves sadly spiraling down and landing at our feet.

Come winter, we siblings were thrown together once more in our drafty little farmhouse, marooned with a moody dad and a weary mother while our woods lay shrouded with snow, unobtainable.

The next spring, we happily returned to our woods, raking last fall’s leaves from the pathways, and resetting the bridge which had been dislodged by a winter deluge. Marshall restlessly plotted more new trails, and we spent a solid week creating a space at the east end of the original route, where we placed three beat-up metal lawn chairs. From this spot, we could sit and spy into a local farmer’s field.

It took the farmer, a nearby neighbor named Harold French who was our father’s age, several days to plow, disk, and plant the field, and I often wondered if he sensed we were watching his work, the small openings in the brushy green foliage framing his efforts like a television screen. Once, when his tractor came close by, he turned his head and looked at exactly where we hid behind the screen of foliage that skirted the woods. We froze in place. If Harold saw us, he did not stop.

A tall, perfectly straight tree, an oak in its early prime, caught my brother’s attention one hot summer day as he, our little sister, and I walked through our wooded garden, swatting at insects and wiping sweat from our eyes. Looking back now, I think the sticky heat and the pesky bugs had put us all in a bad mood. I guess we were unhappy pigs that day. Marshall stopped cold in the middle of the dirt path, causing Karen and me to knock into him. The tree rested a stone’s throw from where we stood, and Marshall began gazing at its dimensions, as if he were sizing up an opponent for a fight.

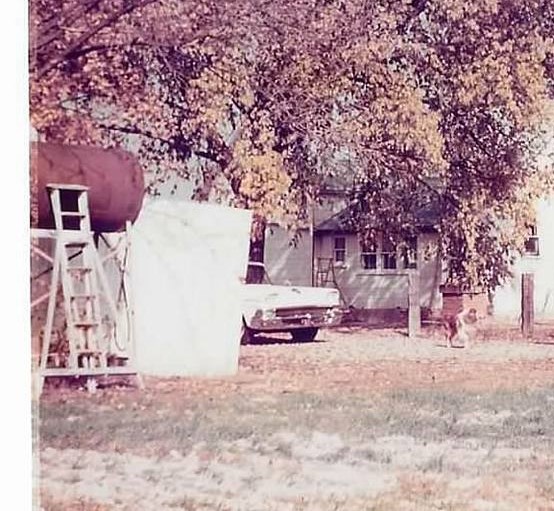

I’m on the right.

Marshall plunged into the undergrowth to get a close-up look, and Karen and I followed. Our brother put his arms around the tree at our waist level and embraced it with a little room to spare. It occurred to me, as I watched him make this odd calculation, that both he and the tree were as trim and straight as arrows. Finally, he turned to Karen and I and said, “This baby’s coming down.” Then he gave us that grin that said, this is going to be fun.

Like a bystander drawn into a violent mob, I quickly caught his enthusiasm and started shaking my head in the affirmative. Soon, we were looking at angles, at where we might cut into the tree, at where we might want the tree to land. We were filled with excitement and purpose, pioneering again.

At some time during these computations, Karen trotted home.

The condemned tree was located deep in the woods, far from our parent’s prying eyes. The effort took us three full days. For the job, we sneaked out two essential things from our garage where Dad kept what few tools he had—a dull ax with a heavily taped handle and a corn knife that had been fabricated by our Grandpa Mills and which looked like a crude sword. Starting the first morning, we spent hours at chopping, me swinging the dull ax and Marshall the corn knife, each of us flailing at the meat of the tree with manic purpose, grunting with each swing, our arms and shoulders eventually trembling with exhaustion. By the end of the day we were surprised to find that wicked looking blisters, like a curse, had risen on our palms, bloody things that would take weeks to heal. The only bit of revenge the silent tree would receive. Mom raised a worried eye when she saw the blisters that first evening and gently rubbed pungent smelling ointment on our wounded palms, all the while wisely failing to inquire about what we had been doing.

The second day we sneaked out a pair of Dad’s work gloves to protect our blistered palms and took turns chopping at the tree with the ax, our movements now made slow and jerky by fatigue and pain.

Late in the afternoon of the third day, while I was doing most of the chopping, and Marshall knelt on one knee nearby, the corn knife down at his side, a sharp cracking noise erupted and became a full-bore scream of splintering wood. I swiftly stepped back from the tree. Marshall moved so quickly, he seemed to go from sitting to standing without any in between movement.

The tree began to topple, slowly at first, in movie-like slow motion, then in full speed collapse, the ground shaking beneath our feet when the tree landed, dust flying everywhere.

Marshall raised the corn knife like a Japanese soldier giving a banzai and let out a loud whoop, sweat rolling down his face.

I was stunned. The magnificent tree lay before us, a mammoth broken corpse. The tree’s fall had also taken down several smaller trees and undergrowth with it, leaving the woods with a sad little hole in its canopy. Knowing that there would be more cutting down of trees, I said, half under my breath, “We’re not pioneers anymore, we’re robber barons.”

The history lesson was apparently lost on my brother, him turning to me and saying, “Remember to keep your mouth shut about this, Doc.”

He never ever had to remind me.

A few years after Marshall and I cut down that first tree, and several others in our woods thereafter, we started working for our Grandpa Mills and for several other farmers, Marshall driving tractors and me laboring in the sun-blasted hay fields. Soon after that, driving around in cars and high school sports took up even more of our time. In this process, our beloved woods slowly faded from our minds, our fun and efforts there in those golden days of childhood summers less and less remembered. What few times I walked through the woods, I noticed where we had chopped down trees and saw where new growth had taken their places. Just before I left to go away to college in 1969, my siblings and I learned that almost all the woods we had so happily played in when we were young did not belong to our family after all, but rather to Harold French, the farmer we had so enjoyed spying on as he planted his field. At that point, the information simply had no impact.

The last time I talked to Harold French was at my father’s funeral, in 1978. My family was in great shock at the time, dad having suddenly died during the 1978 Blizzard, while on the job at the Illinois Department of Transportation. Harold approached my siblings and me as we stood in front of our father’s dark blue, flower-adorned casket, receiving those paying their condolences. As he drew closer, I suddenly thought of all his trees we had so thoughtlessly destroyed for fun, for something to do, trees that would have been worth some money had we not chopped them down.

Harold gave us a shy, sweet smile, patting each of us on the arm.

“Keith was a good man,” Harold said.

After some small chitchat, Harold turned to leave, but I stopped him, explaining that I wished to apologize for all the damage we had done to his woods, especially the cutting down of all those trees.

“I really feel bad about that,” I told him.

Harold just smiled and said, “I knew you guys were doing all of that damage, but you seemed to be having so much fun, I just couldn’t bring myself to say anything.” With that, Harold French stepped from the line, heading to the back of the funeral home to find a chair, his head bent down and shoulders slumped, leaving me to ponder the mystery of grace.