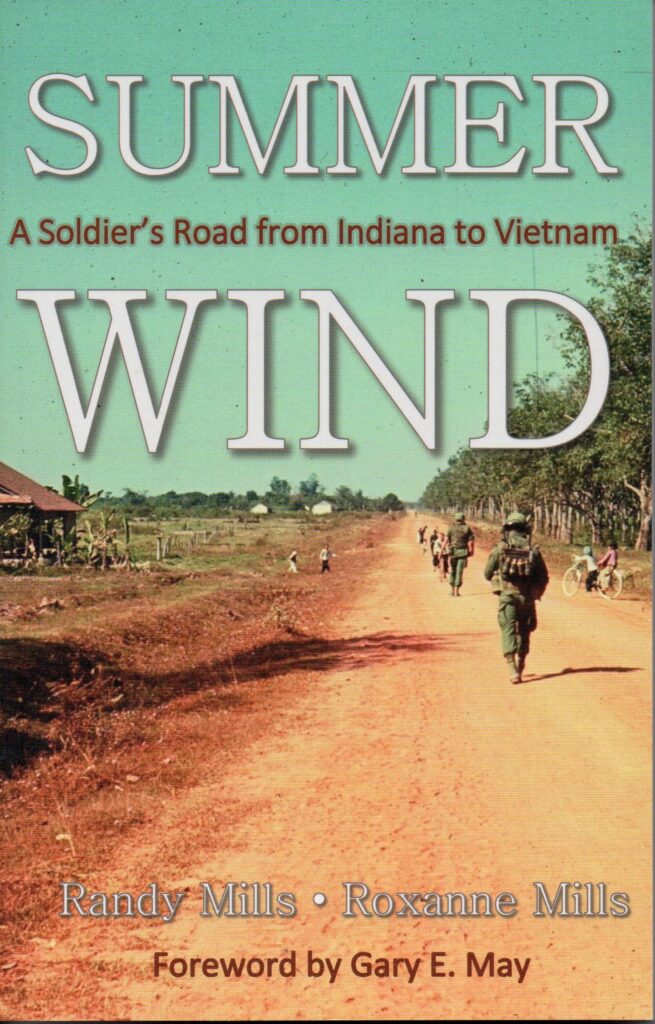

Tobey Herzog, in his book, Vietnam War Stories: Innocence Loss, believed there were lessons to be learned from Vietnam War accounts, lessons concerning authentic leadership, the price of war, and why war should be avoided if at all possible. In gathering data for our book, Summer Wind, A Soldier’s Journey from Indiana to Vietnam, my wife, Roxanne and I discovered detailed information about Vietnam War army medic Wayne “Doc” Bates, information that I share now in the spirit of which Herzog wrote.

Wayne Bates was born in California in 1938 to Pauline and Gordon Bates, joining the army as a careerist in 1957 and training as a medic. In 1963, shortly before the war was starting to heat up in Vietnam, he married Karen Thompson of Paris, Missouri. As the next two years rolled by, the Bates couple must have watched with great anxiety as the war in Vietnam accelerated, pulling in more and more troops. In 1966, Bates finally received orders to deploy to Vietnam, the fighting having increased the need for more combat medics.

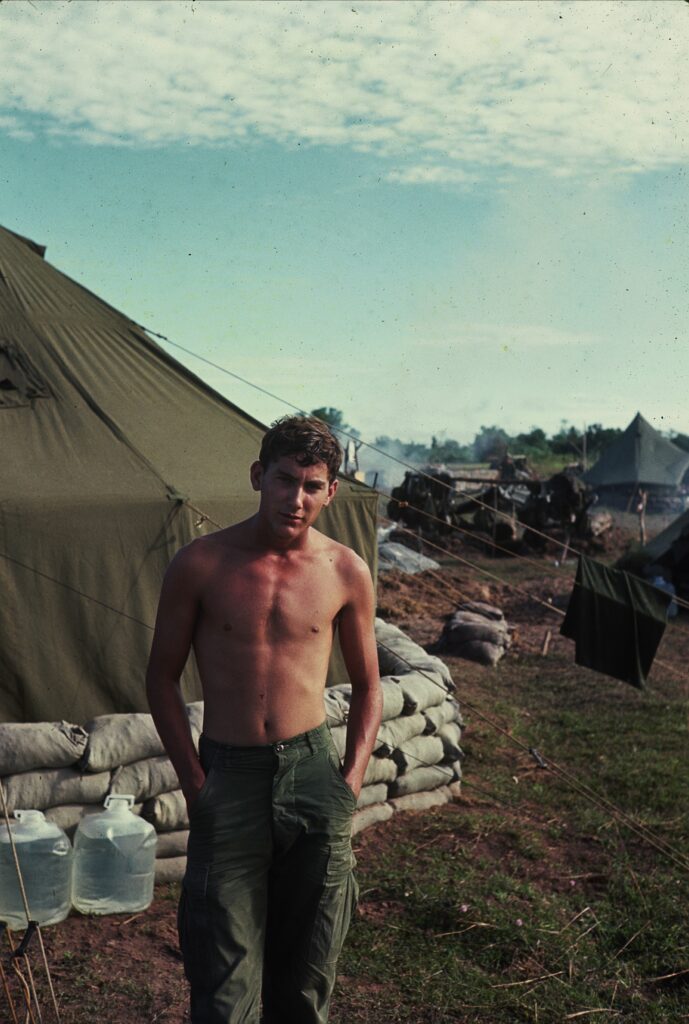

Doc Bates came to Claymore Corner, a small primitive base thirty-five miles northwest of Saigon at the beginning of the 1967 Christmas season, at a time when the men there were especially down and gloomy. A few days after Bates’ arrival, the new company commander, Howard “Dutch” McAllister, himself fighting depression as Christmas grew near, noticed a small, scruffy, artificial Christmas tree that sat on some flat rocks just outside the mess tent. He also noticed something peculiar going on around the tree every evening. While soldiers listlessly moved through the mess tent receiving their evening meal on steel trays, McAllister spied one soldier carefully brushing dust from the sad-looking Christmas tree each evening. Like everything else on the base, a fine patina of red dust from the day’s truck convoys had collected on the tree, making the soldier’s efforts basically useless. When McAllister finally drew near, he realized the man faithfully tending to the shabby tree “was the company’s senior medical aid man, Doc Bates. He was short and compact with a thatch of reddish-brown hair and a quick smile.”

McAllister approached the quiet medic, asking him, “What’s this, Doc? First aid for the tree?”

Bates laughed and replied, “Just trying to make myself count, Captain.”

McAllister was not surprised by Doc Bates’ care of the ragged looking tree. He had frequently watched the senior medic generously sharing his precious water and cigarettes with the other men in the field and had also watched as Bates “served food humbly on the chow line while waiting to be the last to be fed. His kind quiet acts were greatly appreciated, lifting the spirits of young men who were far away from their homes and families and who constantly faced difficult and often dangerous tasks with little rest. It was a true example of Christmas spirit giving.”

In Vietnam, Christmas cheer was soon forgotten. Just after the holidays, after the scraggly Christmas tree had been disposed of, Alpha Company pulled up stakes at Claymore Corner and moved to an even more remote and primitive base called Normandy I. This new location was farther away from major army and air bases and closer to the so-called Iron Triangle, where enemy activity was more prevalent. Alpha Company also picked up more patrol orders. On these grueling patrols, Doc Bates, like other medics, served as a rifleman, until any of his men on patrol were injured. However, while many medics carried M16s, Bates sported only a sidearm, a .45 caliber pistol, along with several magazines in one of his cargo pockets. Doc Bates also carried a few grenades, which were stuffed into cargo pockets, a few flares to properly mark landing zones, and a poncho.

who captured Doc Bates in several photos

There were also the items Bates carried on patrol that were unique to an army medic—a green pouch that was stuffed to the brim with abdominal dressings, which were large bandages; battle dressings, which were medium-sized dressings; and four to five rolls of gauze. Several morphine syrettes completed his medical kit bag. Smoke breaks were essential to get the men through a patrol, and one other “doctoring” item that Bates brought—for his own pleasure, and for the pleasure of the men he served—were several packs of cigarettes.

One thing Doc Bates did find difficult to put up with was his helmet, a thing that flopped around on his head when he ran. The helmet was not bullet-proof and was only intended to protect troops from shrapnel.

Dick Wolfe, a mortar man in Alpha Company, was a superb amateur photographer and loved to take photos to send to his family back in Princeton, Indiana. Many of the snapshots he took featured Doc Bates. Shortly before the company went out on one patrol, Dick took a shot of the serious looking medic kneeling on one knee, his holstered gun prominently displayed, his kit bag at his side, and a cigarette dangling in one hand. He even wore the uncomfortable helmet. It would be the last photo of Wayne Bates ever taken.

On 3 January, Bates and his company hiked some distance in the steaming heat from their Normandy base to a location near a little village called Xom Bung. There they were met by helicopters that flew them back to the safety of their encampment. Dick Wolfe wrote his mother, after returning from the long, grueling tramp, “This is the tiredest I’ve been for a long time. Set ambush all night. 100 percent awake. Then, 9 clicks out and 10 clicks back through rice paddies and jungles. But I figure I’d better write.”

Dutch McAllister wrote in his diary about the long, tiring sweep as well. He had expected some action and was surprised when none occurred. “It was something of a disappointment in execution as we found nothing at all. No enemy nor any indication that he had been in the area recently.” The company commander also noted the attention “Doc Bates gave to the men, making sure they stayed hydrated and had plenty of smokes” during short breaks.

It was, however, a fateful march, the lack of any enemy contact giving Alpha Company officers and men a false sense that the enemy lacked a presence in the countryside.

The morning of 6 January, a Saturday, dawned hot and humid, not a big surprise to anyone in the company. At 7:00 a.m., Captain McAllister ordered his men to begin climbing aboard the helicopters that would take them to what had been the termination point of their previous patrol through the area three days before. The anxious men did not take heavy packs: just their weapons, ammo, water, and some C rations. Of course, Doc Bates and the other medics in the company brought their kit bags. An over preparer, Bates carried two bags.

Alpha Company was in the air for about twenty minutes before the helicopters began their circling descents. Stomachs now tightened, and certain parts of the landscape caught the soldiers’ attentions. Below lay a geometric-looking set of rice paddies that bordered a patch of jungle. A rough, sinister trail snaked up a hill past a dilapidated-looking cemetery and disappeared into thick foliage. Immediately to the company’s north loomed a larger, heavily tangled vegetative area of jungle, brown in many places in the hot, dry season. A muddy stream meandered nearby.

Once on the ground, the company of just less than one hundred men formed into two columns and cautiously moved away from the rice paddies and toward the first tree line of jungle. Someone said the village of Xom Bung was nearby, but few paid any attention to the information, already too overheated and sweaty to care. At first the men were able to stay spaced about five meters apart, slogging up a narrow dirt path that ran haphazardly into a tall jungle thicket, their eyes scanning back and forth like radar.

As the company started to enter the jungle, Fourth Platoon, which included the picture-taker, Dick Wolfe, was ordered to stop and set up a U-shaped defense position facing back towards the rice paddies, as it was a typical trick for the Viet Cong to suddenly attack a patrol from the rear. More importantly, if Captain McAllister and his small command group and the other three platoons were suddenly attacked by a larger force, they would be able to pull back through Fourth Platoon’s defense line and escape to the rice paddies, where they could reform to defend themselves while American artillery and air fire power could be called down on the enemy.

Beyond the Fourth platoon’s defensive line, the rest of the company were soon strung-out and separated. Sudden, the sound of gunfire came rolling down the line, catching every man’s attention. The firing was sporadic, but McAllister ordered the men ahead of his command post group to pull back a short distance and hunker down so that artillery firepower from a nearby base could be brought to bear.

After a fierce bombardment that literally shook the ground, Alpha Company men moved forward again, only to be met by a hail of gunfire and rocket propelled grenades. An overhead observation plane radioed down to McAllister that enemy troops were now emerging from hidden bunkers like “angry ants from an ant hill.”

The two-day battle of Xom Bung had begun.

In the growing confusion, McAllister ordered Alpha Company columns to begin moving in orderly fashion back through the Fourth Platoon defense area and down to the rice paddies, where the berms would provide a better defensive position and outside fire power could be called in to knock out the enemy. The Viet Cong, however, moved swiftly to outflank Alpha Company. Their strategy included getting next to and among the American troops so that American artillery and planes could not be used without killing Alpha Company men. This tactic was called “grabbing the belt-buckle.”

A short-lived, well-ordered retreat turned chaotic, individuals and groups of Alpha Company soldiers getting separated from each other, causing the fight to deteriorate into private pockets of small raging struggles, the air filled with the ear-splitting sounds of gunfire and grenade explosions, and the terrible screaming of the oaths and the cries of fighting men.

In his haste to get a command post set up in a safe area of the rice paddy dikes, Dutch McAllister recalled that the movement back to the rice paddies seemed to be working, “except that I could not raise the weapons platoon on the radio. I thought I saw Sergeant Dempsey [Fourth Platoon leader] on the edge of the wood line.” Then McAllister saw Doc Bates “running toward the wood line, helmet pushed back on his head, a kitbag swinging in each hand.” Of all things, McAllister was suddenly reminded of how the thoughtful medic had so carefully tended the ragged Christmas tree at Claymore Corner.

At this moment, a sniper’s bullet pierced the captain’s stomach, knocking the company commander to the ground.

While life-threatening, McAllister’s horrendous injury would not kill him. As he fell the day of the battle, McAllister did not know that Fourth Platoon, the group that photo taker Dick Wolfe belonged to, was being savaged by the final blow of the enemy’s flanking movement. Fourth Platoon member Ron Whitt, who was experiencing his first taste of combat, found the unexpected fierceness beyond believing. “I was eighteen at the time and thought we were all going to die.” The next few minutes would also be seared forever in the mind of Fourth Platoon newcomer Scott Washburn. “It was as though the earth had opened up and was on fire. The sound was deafening and the smell acrid and the intensity of battle immediate. It was all pretty hectic—loud, smoky, tracer rounds everywhere, fast, sudden and explosive—with RPGs, mortars and grenades going off.”

Then, before Washburn’s very eyes, hardly five meters away, three comrades, including Dick Wolfe, “went down almost instantly.”

A trooper called Fudge had been hit in the back, his radio taking the brunt of the hit and thus saving his life. He had also been hit in the groin and shot through both shoulders and had both legs broken by a grenade blast. Bob Hilley was hit in the head and, by another account, in the groin area, with a RPG round. Wolfe went down like a rag doll at this time, too, but Washburn was unable to judge whether his wounding was fatal. At this same point, Scott Washburn was struck in the small of his back by fragments from an RPG round on both sides of the spine. He screamed for medical aid.

Nearby, Fourth Platoon Sergeant Hylton Leftwich reacted quickly, hollering for a medic. This was probably when Captain McAllister saw Wayne “Doc” Bates running up to the wood line where most of the action was now occurring. Leftwich was pleased with the medic’s calmness, as it was his first time to be in action. Leftwich recalled, “I heard one of my men yell behind me, ‘Medic! I’m hit! Medic!’ So, I looked at Doc Bates and said, ‘Hey, Doc, let’s go. We got one.’ He said, ‘Okay,’ and we jumped up and ran towards the wounded man.”

Bates, taking super-long strides, moved so quickly that he soon got several paces ahead of Leftwich. As Bates ran, arms pumping, his helmet came off. Leftwich hollered and told the medic that he had better put it back on.

Bates yelled back, “I don’t need it.

Leftwich caught up with Doc Bates just as the two got to Scott Washburn. Luckily, the sergeant happened to be looking up just as Bates began checking on the wounded soldier.

“There were two VC standing there, about fifty feet away, real close. I figured Doc hadn’t seen them, so I gave him a shove and pushed him on the ground. I hit the dirt as well. I had my hand on Doc’s neck/shoulder somewhere in there, and the VC were shooting at us, kicking up all kind of dirt around us.”

When the Viet Cong stopped firing and disappeared back into the foliage, Leftwich told Doc Bates “to wait a second or two before we moved. I wanted to make sure the VC had left. When I got up, Bates didn’t move, and I looked down and saw that his helmet was still off to the side. He had a crease in his right temple from a fragment wound, something his helmet would have prevented. I knew right away that he was dead.” The battle took two days to play out, the VC survivors disengaging and disappearing into the remote countryside. Wayne Bates, Robert Hilley, and Dick Wolfe all perished at the same place in the early part of the struggle. One other Alpha Company trooper, John Galata, died that day too, and dozens of other Alpha Company men were severely wounded in the battle. Many survivors of the battle would carry trauma home with them.

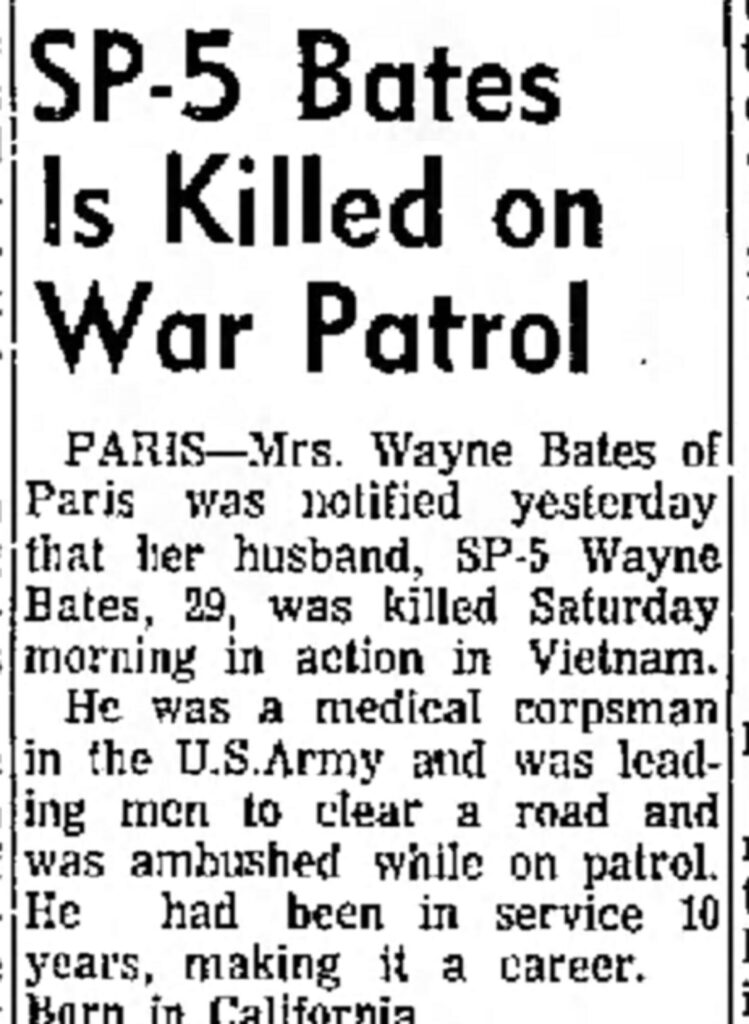

There were four short newspaper announcements telling of the death of Wayne “Doc” Bates. The first article, a short piece in the Missouri Mexico Ledger published on January 8, 1968, related that Bates had been in the army eleven years and in Vietnam “about one month.” Also reported, “Mrs. Bates was told by army authorities that her husband was with a group that was clearing an area when they were attacked by Viet Cong guerillas.” On that same day, Missouri’s Moberly Monitor Index had a somewhat similar article headlined—SP-5 Bates is killed on War Patrol. This piece offered a slightly different version regarding his death, reporting, “He was a medical corpsman in the U S Army and was leading men to clear a road and was ambushed while on patrol.” Neither of these accounts, or the two others that were published in two other Missouri newspapers were completely accurate, and none came even close to conveying the nature of Wayne Bates’ death and his heroic actions that day. A month or so later, one last short article reported of Doc Bates being awarded a Purple Heart and the Silver Star, the third highest military award for combat “gallantry.”

of Wayne “Doc” Bates

A final note to this story: Captain Dutch McAllister would survive his injury and spent the rest of his life remembering the servant leadership of Doc Bates, especially around the Christmas holidays, the sight of a Christmas tree always moving him to tears.