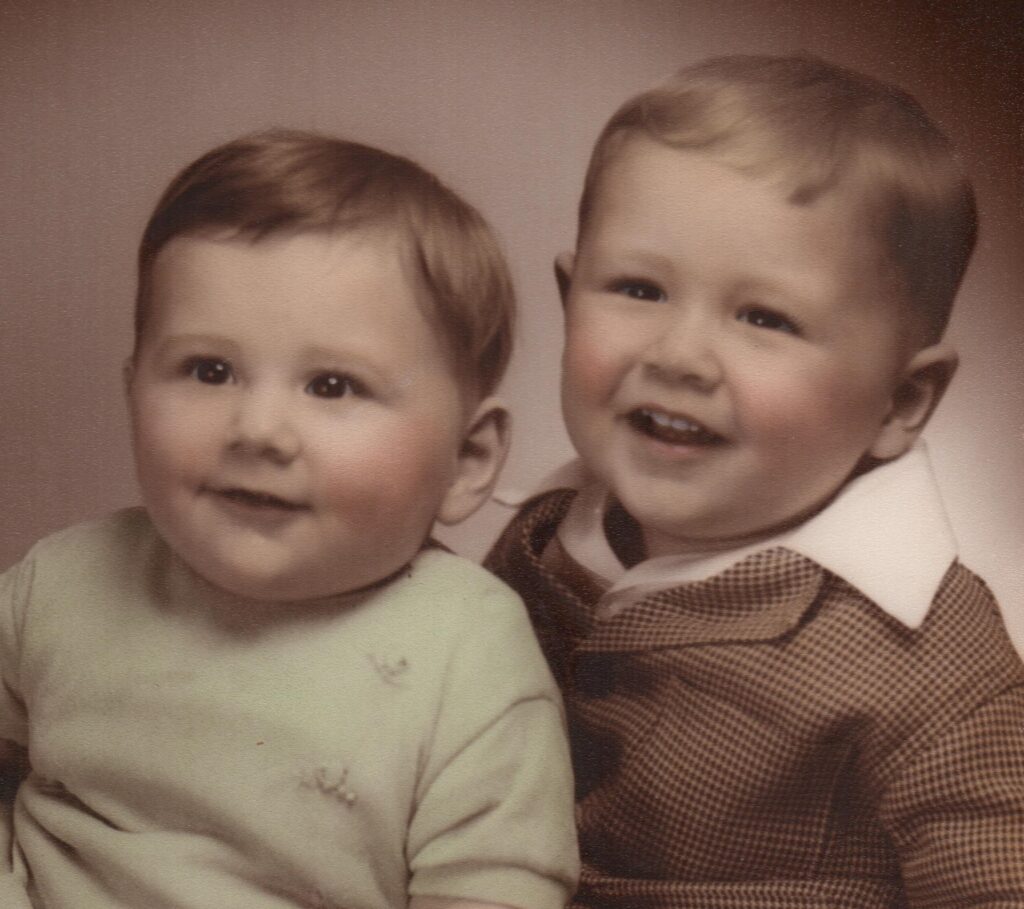

To have a brother eleven months older than you, an Irish twin, is to have a constant companion and a bitter adversary rolled up into one. For me, from what I was told by our mother, the adversarial aspect came first.

Marshall was a biter, and I was hardly able to fight back while a toddler. Given that our mother was so overwhelmed with having to deal with our baby sister, Karen, I was often left to fend for myself, our overwhelmed Mom only checking in on us when she heard horrendous howling in the next room.

One day mom heard loud cries of anguish, shrieks like she had never heard before. They exploded from the kitchen, loud wailing sounds of outrage that were unusual, as they were not mine.

When Mom ran into the kitchen, our baby sister on her hip, she found Marshall with a fork stuck in his shoulder, walking in a circle, and wailing like a banshee. I was sitting on the kitchen floor playing with a toy. I cannot image plunging a folk into Marshall’s shoulder, yet, there it was, like an extra little arm protruding from his body. Perhaps he had somehow fallen on it. At any rate, Mom tells that Marshall never bit me after the fork episode.

Once Marshall and I were beyond the toddler stage, there was less fighting and more companionship. We slept in separate bunk beds, but at night, in the cold winters when air seeped through the casements of our ancient farmhouse bedroom windows, swirling over us in invisible currents of air, Marshall would climb down from the top bed and lay beside me, placing the bottom of his feet against my legs to stay warm. At the kitchen table during the winter months, we bent forward from our pushed together chairs, our heads almost touching, concentrating fiercely on coloring projects.

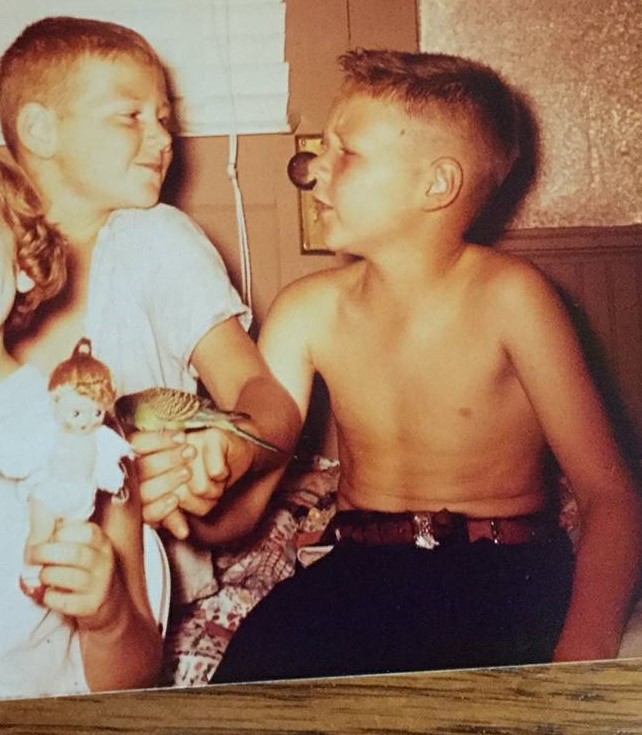

In warm weather, Marshall and I played outside on our swing set or crouched down on a bare patch of the yard next to the old smoke house to play with our toy tractors and trucks, the red and yellow paint scratched from their surfaces from hard use. Mom could look out the kitchen window at any time to see us squatting in the dirt and know that we were safe.

If it rained, Marshall and I settled into our abandoned chicken house or in our ancient barn, our two dogs cuddling next to us. We still fought some, brief pushing matches that ended quickly, as we were of the same size and strength by then, a fight serving no purpose, pulling us from play. We most often got along famously, even lovingly. I lacked a nickname at this time, while Marshall was called Bud, our mother having given Marshall the affectionate nickname when he was a baby. As a child, I envied the tender way that name rolled off my mother’s tongue whenever she called for her firstborn. As we grew older, she still used the name at pivotal events—birthdays, graduations, and such like.

Marshall must have been moved by this miscarriage—one day on our smoke house playground, he anointed me with the only nickname I would ever have, one that was rarely used and then only by my brother. The name was “Doc,” and while it was true Marshall had given me the nickname common to our father, it was certainly better than nothing.

This détente did not last. As my brother and I approach puberty and gained muscle and hormonal restlessness, incidences of fighting increased. We compared bicep size when we were in a playful mood, not much difference there, wrestled hard enough that we broke down a couch in the living room, but never gave it our all, fearing that the other might win.

If real anger was involved, the one who was not mad knew to run.

But the question of who was strongest did not go away, growing into a nagging, unspoken presence, a frightful, possibly ego shattering question for two boys in the process of slowing moving toward young manhood. Yet, we sorely avoided any kind of major physical contest. It would be humiliating for Marshall to be defeated by a younger brother he had once easily bested.

My situation was more existential. And more perilous.

Marshall had received the full attention of the first born for almost a year. I, on the other hand, was obviously a surprise, coming on the scene eleven months later, most likely unwanted. My parents had chosen a girl’s name before the birth, Donna Sue, maybe hoping that not having a boy’s name picked would work some sort of primitive magic and they would end up with both a little boy and girl. If so, they were disappointed. They scrambled for a boy’s name, coming up with a short simple one—Randy.

A baby girl, Karen, did come along two years later, exiling me to the middle child position, squeezing me between my two siblings where I received even less attention and felt even more doubtful about my place in the family. Thus, whatever scraps of noteworthiness I might pick up were essential, including being at least as strong, if not stronger than my brother.

Before any encounter occurred answering the question of physical supremacy, Marshall’s path and my path began to diverge. He started school a year earlier than me, and I spend warm sunny days waiting outside in the wide shade of an ancient oak, waiting and lonely for him to return home in a dust covered yellow school bus. In the process of going to school, Marshall found new friends whose names and adventures now popped up in his conversations, leaving me secretly sad. Our paths forked even more the first time we sneaked up to our Mills Grandparents by foot.

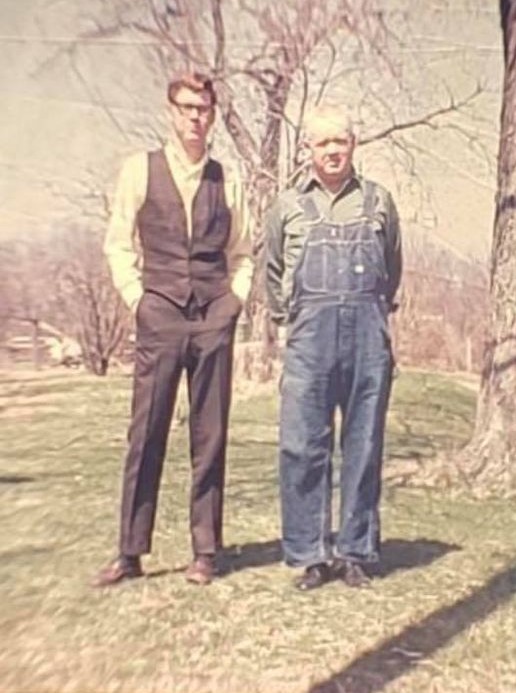

We were nine and eight when we trekked without our parents’ permission on what was called the Peach Orchard Road, a dusty track that followed the edge of a field, the path coming to meander up a steep hill and through the remains of a once thriving orchard at the top, next to where our grandparents’ house sat. There too, across the road from the house, sat a shed, a long barracks-like structure once used to package peaches for market and where Grandpa Mills now had his workshop, the very heart of his simple but pleasant life. This would have been in the rural farming world of the early 1960s, when young boys longed to join their older male kinfolk and neighbors in the fields—driving tractors, hauling hay, shoveling mature—these being the rural initiations into young male adulthood. Our grandfather Mills’ status in this culture was at the topmost spot, and to be complimented by him for a task well done was to be anointed.

We walked into the darkened building with our heads bowed. Grandpa was short, five feet, six inches, maybe, but barrel-chested and thick, like a football running back, his blue eyes alive and twinkling whenever he was engaged in any kind of work. He acknowledged us with just the slightest nod of his head, without surprise, as if he had been expecting us. We knew to go quietly to one side, standing against the wall while Grandpa absorbed himself with working on what my brother whispered to me were the pieces of a tractor carburetor lying on a workbench. A single focused beam from a large lamp was aimed on the project, the light making the oily metal parts gleam like pieces of a treasure.

Marshall turned his head ever-so slightly sideways, like a bird after a worm, watching every intricate motion our Grandpa made. My eyes, on the other hand, flittered about the room, noting the large vises fastened down on either end of the long work bench, the contraptions looking for all-the-world like medieval instruments of torture. A small forge, an anvil, and the tools that went with them lay nearby, along with a large electric grinder and sharpener, the latter used to hone shovels, spades, and hoes. It was an alchemist’s lair, a fabricator’s delight, and the not unpleasant smells to young country boys of dust, oil, and grease permeated the air.

Restless Marshall did not stay against the wall long, moving boldly to the workbench with me three steps behind. Soon, my brother’s and grandpa’s heads were almost touching over that damn carburetor. No room left for me. I stepped outside the shed, squinting into the sun, drawing in a deep breath.

No one called from the shed for me to return inside.

Just across the road stood our grandparents’ home, an older farmhouse with white asbestos shingles, yellowing with age. I could see Grandma Ruby through a window, moving around, her head bent downward, her attention fastened on something I could not see. The front door opened into a pleasant sun room, a light-drenched enclosure with tall windows covering the entire south and east sides. Here, Grandma Ruby kept a jungle of plants year-round—ferns, snake plants, golden pothos, dumb cane, African violets, aloe vera, begonia rex. It was one of these plants, the African violets, that she could not coax to bloom, that so captured my grandmother’s attention the day I stepped out of Grandpa Kermit’s workshop and walked across the road.

****

Unbeknownst to my brother and I, a die was cast that day. While Marshall continued to hang around with our grandpa, helping him with farm work, my immediate work destiny soon involved weeding Grandma’s flowers and her immense vegetable garden and moving heavy metal tubs that housed giant caladiums and the deep dense soil that sustained them. Each tub approached a hundred and fifty pounds, enough to challenge a grown man. But having failed to pass some not understood test back in Grandpa’s workshop, I was overly determined to prove myself to someone. Somehow, I moved those tubs all over the place as directed by my grandma, even getting them to and from the basement by myself with the changes of the seasons. Altogether, it was not bad work. Grandma Ruby was tall and big-boned, with broad facial features, large, sad-looking brown eyes, and shoulders that stooped forward in the fashion of her Pierce ancestors. She also possessed large hands for a woman, muscular hands to which the tightest jar lids soon surrendered. Grandma told colorful, interesting, sometimes outlandish stories about the family and the community, going back to her childhood and beyond. She also brought me glass after glass of tea, with more sugar in it than Mom would have ever allowed.

Brewed in the sun, the tea’s potency often made my legs quiver in the night and gave me strange lucid dreams.

It was soon evident that Marshall possessed amazing natural skill with mechanical things, a young wizard. But it was driving tractors and trucks that brought him the greatest joy, gave him the outlet for his impulsive adventure-seeking personality. Grandpa let him drive vehicles to and from and in the fields almost from the start. Marshall was good at that too, soon as competent as a grown man.

But if Marshall was the young mechanical and driving expert in the dawning of our moving into the world of adult work, I was a fledgling Hercules. My budding physical strength was made evident by my successful wrestling with the giant caladium tubs I moved to and from my grandparents’ basement, the effort forging muscles in my chest, back, and arms. Strength at least counted for something in rural southern Illinois, helping me to compensate a bit for my brother’s highly respected driving and mechanical skills.

As Marshall’s status grew in our rural world, my brother and I had yet to find, or even want to find, an arena where the question of who was the strongest could be settled. I had grown a tad bit larger than him, and brawnier, but his constant working with wrenches and driving heavy vehicles in a day before power steering made him forearms as big as Popeye’s. Marshall also had our dad’s thick muscular hands and fingers while I had long tapering fingers, like a writer’s, like our mom’s people.

By the summer of my freshman year, I had advanced beyond moving tubs and pulling weeds for my grandma. I was working in the hay fields—pitching and unloading bales in the hottest, most sun blasted conditions one could imagine. It would be easy to idealize the process of initiation into young manhood that hauling hay offered the rural teenage youth of my generation: shirtless teenage boys in ragged jeans, their tanned skin gleaming with a sheen of sweat, picking up and flinging heavy green bales with amazing precision, grace, and vigor. Such self-assurance, however, was hard earned—the hot, dusty, backbreaking job was hellish, with a group of water-starved wobbly-legged boys pushing Sisyphus’s rock, mindlessly loading and unloading wagon after wagon of dusty, itchy hay in the sultry heat of summer.

Marshall was working for farmers too but doing high profile jobs, driving tractors—plowing and disking. Occasionally, our paths would cross in the hay fields, Marshall on a tractor, cutting or raking the hay to get it ready to bale. He was especially skillful at backing loaded wagons of hay into tight places, an almost impossible job, as I discovered when I tried, my attempts leaving the tractor and wagon in an impossible jack-knifed position and the farmer I was working for shaking his head.

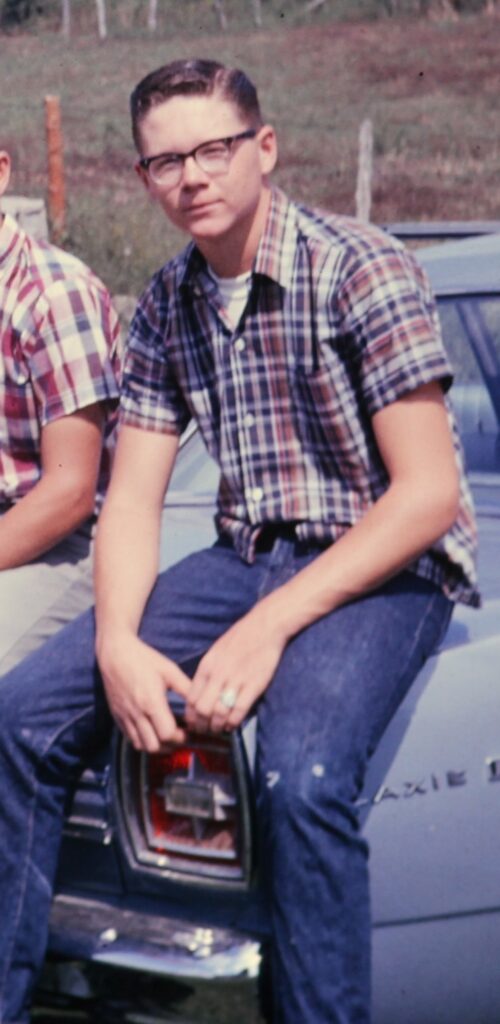

As the summers of our high school years went by, the awareness among farmers of Marshall’s abilities grew far and wide. Meanwhile, I had gained enough respect from local farmers in the hay fields that I was able to put together my own hay crews. I had also begun lifting weights, further adding to my physique and my confidence.

My weightlifting equipment and routine was basic. I had a long iron bar Grandpa Mills gave me, an item he dug around for and found in a junk pile behind the peach shed. His enthusiasm in finding the bar was an anointing of sorts, a sign our diminutive grandfather wished to see at least one grandson muscle up. I had collected just over three hundred pounds of weights—one, five, ten, twenty, twenty-five, and fifty-pound plates that I painted gold. I used a solid hay bale from the barn loft for bench pressing and covered it with a rag rug. I did military and bench presses, as well as arm curls, leg squats, and dead lifts. For pull ups and chin ups, I used a rafter in the garage or a sturdy tree limb. In the winter, I lifted in the barn, big puffs of steam exploding from my mouth as I chugged through my routines. In the summer, I worked outside, in the broken shade of a Walnut tree next to the garage.

Mom grew worried with my obsessive determination and asked me one day, “Why do you punish yourself so much with lifting weights?” I just gave out a grunt and struggled on for another repetition.

Marshall sometimes drifted by while I went through my routine, never stopping to talk, his face as guarded as a poker player. Speaking of Marshall, he had not changed much physically, still with the powerful forearms and hands, but no mass of muscle added elsewhere as I had done by lifting. All this did not matter. We were so busy doing our own stuff that the few times we did cross paths there was only time to nod. We had each reached a place of confidence and contentment, having yet to face the question of which of us was the strongest and both willing to let it go—but, as they say, the best laid plans . . . .

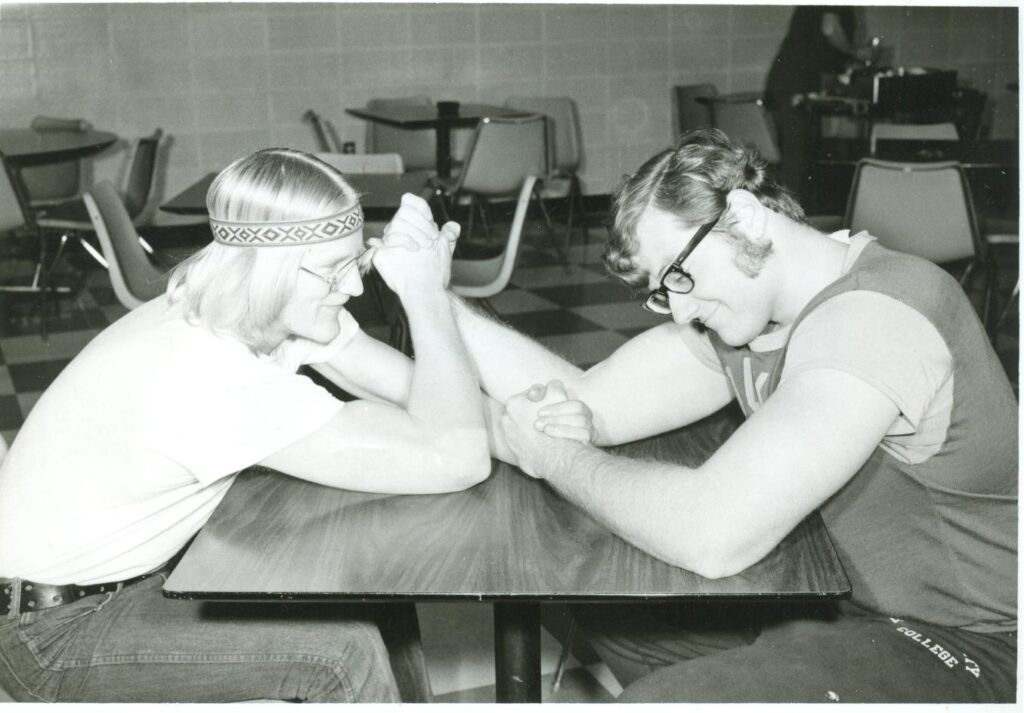

At Bluford High School, my physical build led me to be challenged to arm wrestling contests, until I beat all comers. At that time hardly anyone in rural areas, high school athletes included, lifted weights. Nor had the science of arm wrestling been established—an understanding of the points of leverage and how to use them, the best hand grip, and so forth, techniques that allowed a wrestler with less size and strength to win against a novice who was stronger but unschooled. Thus, the bouts I participated in were uninformed by technique, the outcome governed by brute strength.

After having gone through the high school crowd, I occasionally arm-wrestled Mt. Vernon High School football players too, the few who worked in the hay fields. I beat one, a short heavy-set dude who looked like Hercules, at Leonard Wilson’s store. A couple of older farmers came out to watch, smiling at me, hoping I would carry the day for my rural people.

The jock grunted loudly while trying to pin my arm down, his veins in his neck and forearms bulging under his skin like long fat worms. But I bested him with right hand and left. He was good natured about it, patting me on the back and telling me, “Well, they said you were strong.”

Marshall knew of at least some of these contests, probably all, but he never spoke of them to me.

One summer day a farmer stopped by our house, parking his mud-covered Case tractor in our driveway, and getting stiffly off. He lived in a community next to ours and I knew him only vaguely, having hauled hay for him one time. Marshall went out to see if he was looking for him to do some farm work. To my brother’s surprise, and mine, the farmer asked to talk to me.

The man was a few years younger than my dad and a bit gone to fat. He causally swung his thick shoulders and short beefy arms with the swaggering confidence of a fighter and his eyes were slightly bloodshot, giving him a menacing look that caught my attention. When he spoke to me, however, he seemed shy and embarrassed.

“I hear you’re a pretty good arm wrestler,” he said. “I’d like to give it a try.”

I looked over at Marshall, who shrugged his shoulders, but smiled slyly, a sign to me that he hoped I would meet my match. Also, we each knew the man had a reputation for drinking and fighting and was exceptional at both.

We arm wrestled on the kitchen table. He was nervous before we began, trying to find a hand grip he felt comfortable with. A few dark twisting hairs, the kind that looked like they would ping if you pulled one out, covered his scarred knuckles.

Marshall raised his arm.

The farmer and I both nodded that we were ready.

Marshall’s arm dropped as he shouted “Go!”

I could tell the farmer was angry when he left, turning to us before he climbed back on his tractor, his glaring eyes letting both Marshall and I know that he could beat the heck out of either one of us in a real fist fight.

Then he said something that changed the entire atmosphere, a trickster’s gift. Smiling mischievously, he asked, “Which one of you two wins when you guys arm wrestle?”

Which one indeed.

****

The disturbing question was left unanswered for some time. After I beat the farmer, I would have gladly arm-wrestled Marshall. I was finally confident that I would win, but I felt sorry for my brother, so I never pushed the point. Neither did he.

During my first year in college, I lifted weights with even more rigor and instruction. My poundage rose and I continued to arm wrestle, winning every bout. Life was good. I held one essential skill that placed me a step above my brother in the rural area of my youth—I could lift more weight than him, and, by that same distinction, could logically beat him in arm wrestling. That line of thinking, however, was soon to be challenged.

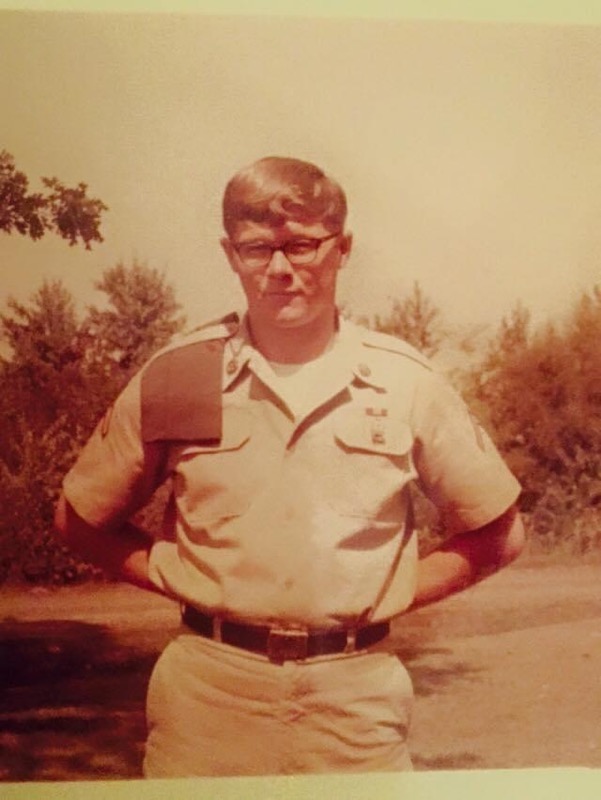

On the second day of summer, in 1971, Marshall arrived at his first stop on his way to army boot camp. I was ending my second year at college and was headed for another summer of work in the hay fields.

I worried about Marshall’s well-being, but certainly not about him being able to make any gains on my status as the stronger brother. His first letter home suggests his travail.

Dear Mom,

It sure don’t take long to get homesick around here. They’ll wake you up at 4:00 A.M. and tell you to get dressed and then they’ll tell you to go back to bed. This reception center is nothing but a stink-hole! This place could make you hate your own mother. They told us today that we wouldn’t get any clothes until Monday. If that’s the case, I’ll get pretty stinky. Be sure to tell everybody hi for me. I haven’t got too much time to write and besides I haven’t got an address yet. I met a pretty good guy from Sterling Illinois, I hang around with. His name is Wesley Phillips. I’ll tell you one thing for sure; I see now why so many guys go A.W.O.L. Well I guess I’ll go and take a shower now. Wesley and I have got to stand fire guard tonight in the Barracks. I’ll either write or call when I get my address.

Love, Marshall

In his next letter came the first hint that my status of the strongest brother would soon be challenged big time.

Dear Mom, Dad, Karen, Randy and Mort,

Right now I’m in a daze because I got up at 3:00 A.M. today and just got off from K.P. I don’t know how I got so lucky to get into this place. I’ve been putting in 12-15 hours every day the sun rises, and I’ve worked my butt off. I was sitting on a car hood today while on a 5 minute break from K.P. Guess whose car it was. The Captains! That cost me 25 push-ups. I had to count them off 1 sir! 2 sir, etc. But I’ll tell you one thing, I’m not the only one that’s had to do push-ups. Everybody’s done at least 25. I’m so tired that I can’t hardly write. Be sure to send me 5 boxes of Skoal fast. I need it because when I get mad at the drill Sgt. I want to grit my teeth, I can chew. We got 2 more drill sergeants today. This can really mess you up because one will tell you one thing and one the other. Be sure to hurry up with the Skoal,

Marshall Andy (Bud)

Push ups! Marshall had never done calisthenics in his life, but now I knew he was doing lots of exercising in his training. The next few letters continued to hint of this and more. Marshall was arm wrestling and winning most of the time.

This AIT is really bad. You can’t imagine the things they make us do around here. I had guard duty last night and only got two hours of sleep. I never felt so tired in all my life. They harass us four times more than in basic. We got to get up at 4:30 in the morning so I’ll only get about five hours tonight because I got fire guard. Tell Randy that I had never been beaten arm rasseling until last night. This guy from Colorado, Mike Magino, beat me. He’s only 5’10” tall but he has really got an arm.

Mike Magino laughed after their bout and told my brother he needed to learn the secret of getting leverage, an art Mike soon shared, as my brother could charm anyone. After this, Marshall could not be beat at Fort Polk. When I saw a photo that Marshall sent home from his advanced training, I was shocked. He had put on weight in his upper body and his arms were as big as mine.

The army started to let up on the draft and began bringing the soldiers back from Vietnam just after Marshall finished advanced training. Marshall was able to shift into the National Guard, where his arm-wrestling skills became legendary at one summer camp training at Fort Riley Minnesota, a version of the story floating around for several years. By then he was called by the nickname of “The General.”

Danny Glover, a fellow guardsman from Bone Gap, Illinois, promoted Marshall around the post as the best arm wrestler, and large bets were placed while the rest of the battalion chose their best man to oppose my brother. The guardsmen made an impromptu lighted ring with a sturdy table and two chairs at the center, a gladiator’s delight. Marshall came dancing into the ring with a towel over his head like a boxer, escorted by Danny Glover. Marshall and Danny had yet to see my brother’s adversary, who turned out to be a three-hundred-pound giant “who looked like he had just arrived from a timber camp.” The worst part was when he put his arm up, he was left-handed. Danny looked at Marshall and said, “General, our boys have $2,000.00 bet on you.” Marshall said, “Danny Boy, I got this.” Fifteen minutes later, Marshall was the Fort Riley champion.

Of course, I was proud of my brother, but damn.

The next summer, when I was home from college, Marshall sought me out at the house. I was lying on the couch Marshall and I had broken years ago while roughhousing, our frugal mother having had it fixed rather than replaced. I knew what he wanted and that it was time.

****

Many years have passed since that arm-wrestling match—years during which Marshall and I each grew strong in our individual gifts. Neither of us would have wanted to exchange places with the other, content with our journeys. Of course, we had no knowledge of what lay ahead of us in the future as we situated ourselves at the family’s kitchen table that day to arm wrestle, purposely doing so when the rest of our family was not home, a guarantee no one would ever know the result.

As we nervously grappled getting our hand grips ready, I noticed how Marshall positioned himself, cocking and placing his hips and shoulder a certain way for the best leverage, knowledge gained from his army buddy, Mike Migino. It was an understanding I still lacked.

As we began bringing up the tension against each other’s arms, unbidden memories of the times we had played together by the smoke house and of the endearing name my brother gave to me flooded my mind, a distraction I certainly had not sought. They came on their own volition, as lucid as if I were back there again.

The arm tension finally hovered at the point of combat, and the thoughts of our childhood play vanished from my mind. There would be no turning back. This was it. Two gunslingers finally halting, face-to face in the middle of the street. High noon.

Marshall said, “I’ll count off Doc, if that’s okay with you.”

I nodded yes.

“1-2-3”

I yelled,“Go!”