My dad loved to quail hunt, a yearly ritual that began during the relatively warm Indian summer days of November. It was a special time of deep blue, cloudless skies that hung overhead like an endless cathedral. Like a farewell kiss from a lover, the warming sun enhanced the various shades of brown and rust found in the landscape while a few pockets of still chirping crickets hiding in the deep weeds conjured up bittersweet memories of the recent summer.

My older brother, Marshall, and I began going on these hunting expeditions when he was ten and I was nine. Always excited about getting out of our small aging farmhouse after the days grew shorter, we would get up early Saturday mornings while it was still dark, helping get Dad’s gear together while he cleaned his “sweet sixteen” semi-automatic shotgun. Marshall carried a twenty-gauge double barrel.

I did not carry a gun, but rather served as someone who flushed out any quails whenever the dogs held point on an area of dense brush. Over my layering of clothes, I wore one of dad’s too big canvas hunting coats that had huge deep pockets in which to carry shot down game. This much was a given, whatever deposits of clothes we wore in the early morning chill, much of it came peeling off and was carried as the Indian summer day progressed.

Our mother often took pictures of our gathering before we marched off to the hunt, Dad, fixing his pipe with tobacco and Marshall playing with our bird dog, Ole Mike.

Dad always took another adult hunter with him on these expeditions, most often Doc Neal, our dentist from in town. The times the dogs came on point were rare. Rarer still was a flock of quail flying away before us in an explosion of round fat feathers. Most of our time was spent walking through fields, Dad parking the car down a dirt lane and letting two anxious dogs out of the trunk. Our caravan would then proceed toward heavy brush, the edges of woods, or tree-dense fence rows, Dad with an unlit cigar hanging in his mouth. As Dad and Doc Neal walked, their shotguns held loosely across their shoulders, they talked and laughed while Marshall and I listened.

More than once, our safari would halt, and we would sit down in an area of soft weeds and wild grass, the men taking the time to bite off a chew of tobacco and petting the dogs.

I was not bored, for it was at these times of rest that I moved away from the others to look for rocks, our ramblings taking me to places where I had yet to search. Rock collecting was as much a passion for me as quail hunting was for my dad and older brother. I often came home from quail hunting with the pockets of my dad’s canvas hunting coat full of small stones and smaller pebbles rather than birds. But I lacked a fundamental understanding about the different kinds of rocks I came upon, and, more importantly, how they got there. I simply selected rocks for my collection simply based on color, shape, or any unusual features.

My rock hunting activities surely annoyed my dad during quail hunts. I would get so distracted in looking for rocks, I’d wander away, forgetting there were three people with shotguns ready to shoot in the direction of anything that sounds like a flock of quails breaking from the brush. Once they fired over my head at a fleeing covey of quail. Luckily, I was deep in a gully, digging at a nice find. Dad raised hell, but I was too happy to pay much attention, having found a large stone that I later learned was a pudding rock, the white shiny rock showing off contrasting bits of red embedded throughout that resembled raisins in pudding.

Doc Neal grinned and shook his head, asking me, “Are you going to carry that thing the rest of the time?” I shook my head yes.

It was when Dad brought a stranger on a quail hunt, a geologist who Dad worked with to help secure oil well leases from the local farmers that I was finally told about the rocks that I so passionately collected. Dad always called the slim geologist by his first two initials—S. R. The first time I reappeared after finding a handful of rocks in a nearby gully while the others rested, the geologist noticed, asking to look at my find.

Even Dad and Marshall drew close as S. R. wiped several small stones against his jacket, even using a little spit in the process.

“Rocks are the oldest and most mysterious things on earth,” he said as he worked the dirt off my finds. He went on to explain how lucky a rock collector like me was, to be in our part of southern Illinois. The details stirred me with wonder.

More than a hundred thousand years ago, the earth experienced an eon of global cooling, causing the icecaps to expand. This, in turn, created a great land-shaping geological force, an immense wall at least a mile high of grinding, gouging ice moving down from Canada, leaving the state of Illinois in its present form—the third-flattest state in the union.

Only the very bottom tier of the state was spared, a land of forlorn and ancient foothills and low jagged escarpments. The Horse Creek region where I lived was located between these two physical landscapes, something of a transition zone, having rolling hills, deep ravines, and small pockets of prairie, and plenty of assorted types of rocks, large and small, carried down by the glaciers and just waiting to be found. The journey aspect S. R. spoke of made me all but tremble in wonder. The geologist also helped me to begin identifying my finds, an array of different types of stones not usually found in the same places, but rolled, crushed up, and pushed here by a great wall of ice.

S. R. only went hunting with Dad twice, Marshall and I finding out later that the excursions were an excuse to spy on the new oil well pumps at a nearby oil field. This explained the geologist’s horrible shooting. But the tutorials he gave to me while we stopped to rest were priceless, firing me up to spent even more time hunting rocks. Unfortunately, I had to wait, quail hunting season being followed by an especially bad winter, knocking me from exploring.

__________________________________________________________

In early March, the first warm days of late winter came. I was back searching for rocks with more enthusiasm than ever. I trekked back and forth in nearby fields, carrying a ragged burlap sack on my hunts, along with a screwdriver to help dig out stubborn rocks from the clayish earth, stalking the local landscape for any glimmer of stones or pebbles. Any kind of erosion in a field beckoned me from the roads I traveled astride my bike, offering the easiest possibility of finding rocks.

I had only to deal with an occasional local farmer, curious as to what I was doing walking back and forth on his property, seeing me knelling down, as if I were praying. I never came back emptyhanded, finding colorful flint pieces, or smaller light gray or white quartzite rocks, along with occasional rounded pebbles of red or green jasper. Purplish pieces of quartzite, some of them banded, might also turn up in a local farmer’s field or a shallow stream. Occasionally, I would even come upon a small, polished piece of agate, with banded colors of red to brown. Most unusual of all were fossilized crinoid stems and pieces of fossilized coral, remnants of a shallow ocean that once covered the state in prehistoric times.

There was occasional deterrence. One farmer, an older man wearing ragged once blue overalls faded by the sun and a patch over one eye, came in long strides across his field to where I labored and stopped my work.

When I told him what I was doing, he said, “Those rocks have been there for a long time. They should not be disturbed. Put ‘em back.”

As the farmer left the field he turned, took off his cap and scratched his head. “What is wrong with you?” he asked.

My rock hunting passion was soon met with another detractor. Marshall suddenly became critical every time I would leave the house to go scavenging for rocks in a field or a nearby gully. More than once he asked, as I headed out the door, “Where are you going?”

The first time he asked, I went to our room and came back with my best pieces, the rocks gently clanging in the cloth sack in which they were kept. I gently placed them out on the kitchen table in what I thought was a pleasing order, in front of the chair where Marshall sat crunching on some dry cereal.

My brother’s immediate responses reminded me of the scripture about casting one’s pearls before swine, but in stages: Marshall’s raised eyebrows, a bored shrug of his shoulders, and a final standing up and to leave the room. His questioning of my rock collecting certainly had its intended affect. Now, when I heard cars, trucks, or tractors coming down the road while I was on my hunts, I hunkered down in the ditches or in brush on the sides of the roads so as not to be seen.

Eventually, I moved away from the main thoroughfares, away from houses and farm buildings and deep into wild, uncultivated fields and dark gloomy woods. I had no rational explanation I could give to my brother, or to the one-eyed farmer, for my rock hunting desire, but I was not about to give it up. A few times in the deeper woods at the height of summer, where bird calls were made mute by stifling heat, I stumbled upon babbling streams whose clear cool waters made rock pebbles gleam like gems. In these quiet, remote places, I could pretend to be Adam before Eve, the only person in the world.

There were dramatic sized rocks to be found. S. R. had called them “erratics,” exotic rocks brought down to Illinois by the continental glaciers. Such large stones, some boulder size, had been pushed and tumbled to the Horse Creek area of my youth, several of these moss-covered behemoths and their smaller brothers littering a stream bed to the south of our house, a watercourse that disappeared into woods at the end of our forty-acre field.

The most curious of these large stones, and by far the largest, was discovered by Marshall and me when I was twelve as we maneuvered down this stream one sharply cold winter day, grateful to have escaped the confines of our small house, moving under a sky that seemed to have been colored by a child’s crayon, it was so startlingly blue.

Stomping through the stream’s patches of vulnerable ice, howling like two pint-sized Vikings, and listening with great satisfaction to the echoing sounds of the ice’s shattering, we came to the center of a long lazy curve in the brook. There, on the right bank, the giant stone lay, a thin layer of snow covering it like a soft gleaming skin.

Marshall hurried right past the stone, still howling wildly as he found yet another large surface of ice to jump on and smash through. His noise making stopped abruptly when he realized I was not stomping through the ice with him.

I must have looked like I’d gone crazy, having taken off one of my gloves to gently wipe the snow from the top of the boulder with my bare hand. I drew my eyes closer to the rock, gauging its makeup, a large gray stone embedded with several interesting pieces of tiny red rocks, like bits of bright candy, giving the boulder a bit of cheeky character.

After receiving some unkind cajoling from my brother, we continued our winter romp, but I no longer hollered like a banshee when we found more ice to break through. The closing day had grown colder, the deep blue drained from the sky, and my mind wondered elsewhere.

Lying in bed that night, I thought about the nature of time, of that great rock and the tens of thousands of years it had waited there, through heat and cold, rain and drought, operating on a clock far different from my own feeble sense of time. I wanted to tell Marshall my thought that the great rock might offer a profound conversation if one would just lie against it and wait long enough. Of course, I did not.

________________________________________________________________

During my eighth-grade year I reorganized my collection of rocks. I placed the fossils I’d found in a three new and shiny cigar boxes—intricate pieces of ancient sea coral, long beadlike crinoids, what the farmers called Indian beads, some as long and big around as cigars, even a couple of brown flat rocks with the delicate imprints of lacelike ferns on them. The smaller colorful rocks that I had painstakingly collected I stored away in less glamorous cigar boxes, one with the lid barely hanging on so that I had to fix it with tape.

Despite what the geologist, S. R., had once told me, I organized my collection of the larger stones once more by size, color, texture, and even unusual shapes. I had several rocks that resembled potatoes, one rock shaped like a boot, and a light gray stone shaped like the state of Illinois, if viewed from a certain angle and with some imagination. These larger rocks I kept spread out on the south side of our family’s little tin-covered one-car garage. Every so often I would run water over them from a hose, the combination of water and light animating them.

I gazed upon these wet rocks for long periods of time, imagining the stories of their long individual journeys from the far north, down into the fields of southern Illinois where I chanced to uncover them. Here were relics as old as the earth, bits and pieces of some possible greater whole, so colorful in their watery sheen that they seemed to vibrate. They were a bit of wonderful mystery in my often-dull world.

Once, while I was lost in one of these thoughtful meditations, my brother Marshall sneaked up to me and grabbed one of the rocks, a reddish-pink one about the size and shape of an apple. He drew back his arm as if he were about to fling it into the field.

“Throw it and you’re a dead man,” I said.

He grinned but dropped the stone.

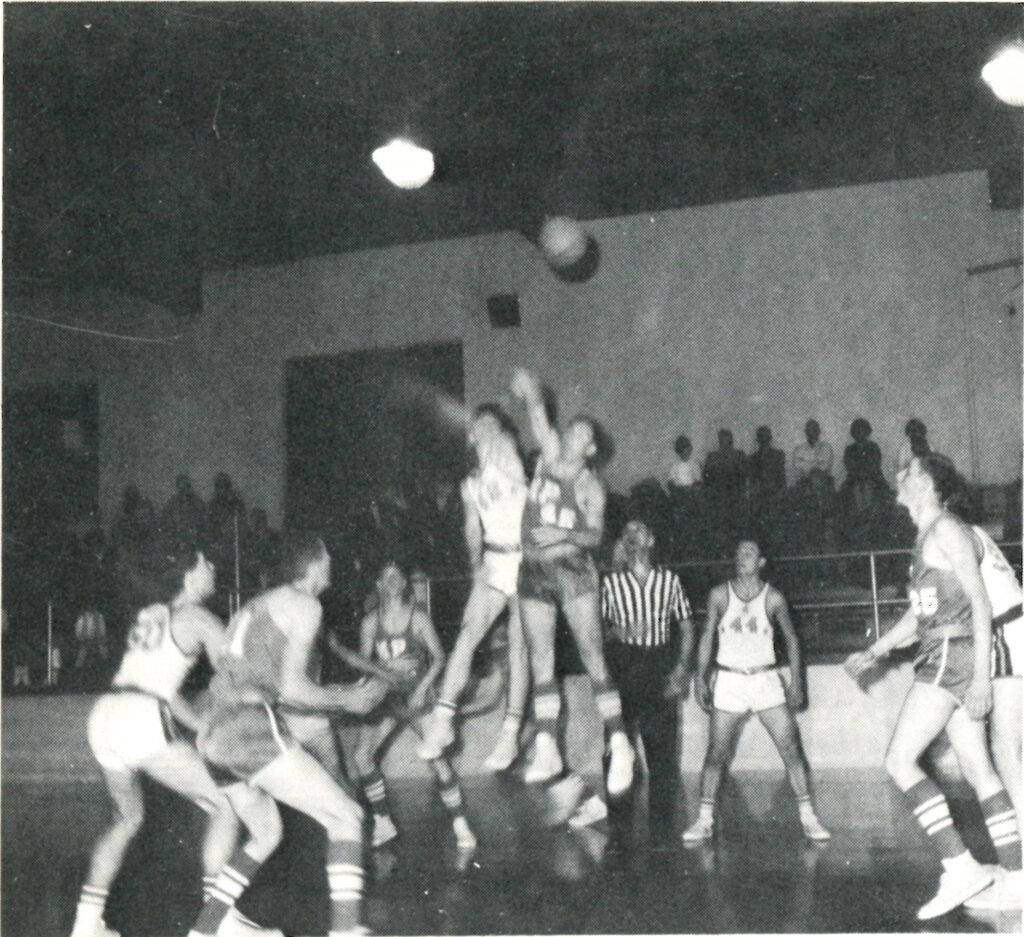

By my freshman year, farmers had discovered I was good at pitching hay, and my forays into the fields and stream beds waned as my working in the hay fields increased. Somewhere around that time I also discovered basketball, or it discovered me. Dad came to every one of my basketball games, and my brother seemed less worried about me now.

Occasionally, when my father mowed our yard during the miserably hot summers, I could hear him cursing over the noise of the mower as he struggled to mow around my rock collection. He began piling the rocks closer to the side of our garage, forming a taller and more compact pile, the easier to mow around. Then, he quit mowing near the spot altogether, allowing the grass, and then the weeds, to reign.

During my last two years in high school, my mind centered on basketball, books, and girls. Meanwhile, with each passing season the pile of once-valued and cared-for rocks seemed to shrink, the stones sinking back into the earth. I lost track of almost all the smaller rocks too, ones I had once safely kept in cigar boxes, save for a small remnant. Perhaps my mother, in one of her famous fits of cleaning, threw them away. By the time I left for college in Indiana in 1969, the bigger rocks lay neglected in a haphazard pile, once powerful talismans now sadly forgotten, the grass and earth slowly reclaiming them at about the same geological rate the ancient glacier from the north had first brought them down for me to discover.