There was something ancient and communal about small-town high school basket in the 1960s—a rite of passage for young male players who turned their lives over to a tribal chieftain in the form of coach, a wise elder who instructed his naive charges in the art and the science of basketball. After many apprenticeship hours of practice came battle, the moments when two small communities would come together in a brightly lighted gymnasium on a cold winter evening to watch and cheer on these young men. Sometimes, it was magical, the game itself bigger and more important than anything outside the building. And as with any ancient communal setting there were rules that could not be broken by a player without horrendous consequences, consequences that in some cases verged on possession.

Although it can not be found in any written form, it was one the oldest rules back in the golden age of high school basketball, expounded on by coaches at the beginning of every high school basketball season. If you played basketball all four years, you probably came to understand the rule’s telling was something of a ritual, a solemn talk meant to bond together a group of young males and keep their minds on the game. While most coaches had witnessed the results of a few players breaking the rule at one time or another, presentations of the rule varied. Some coaches were direct and detailed. Others took a less dramatic “by-the-way” approach. In reality, coaches had no control over the problem.

I first heard the pronouncement from a coach at the beginning of my freshman year, in 1965, after our junior varsity team’s third full practice.

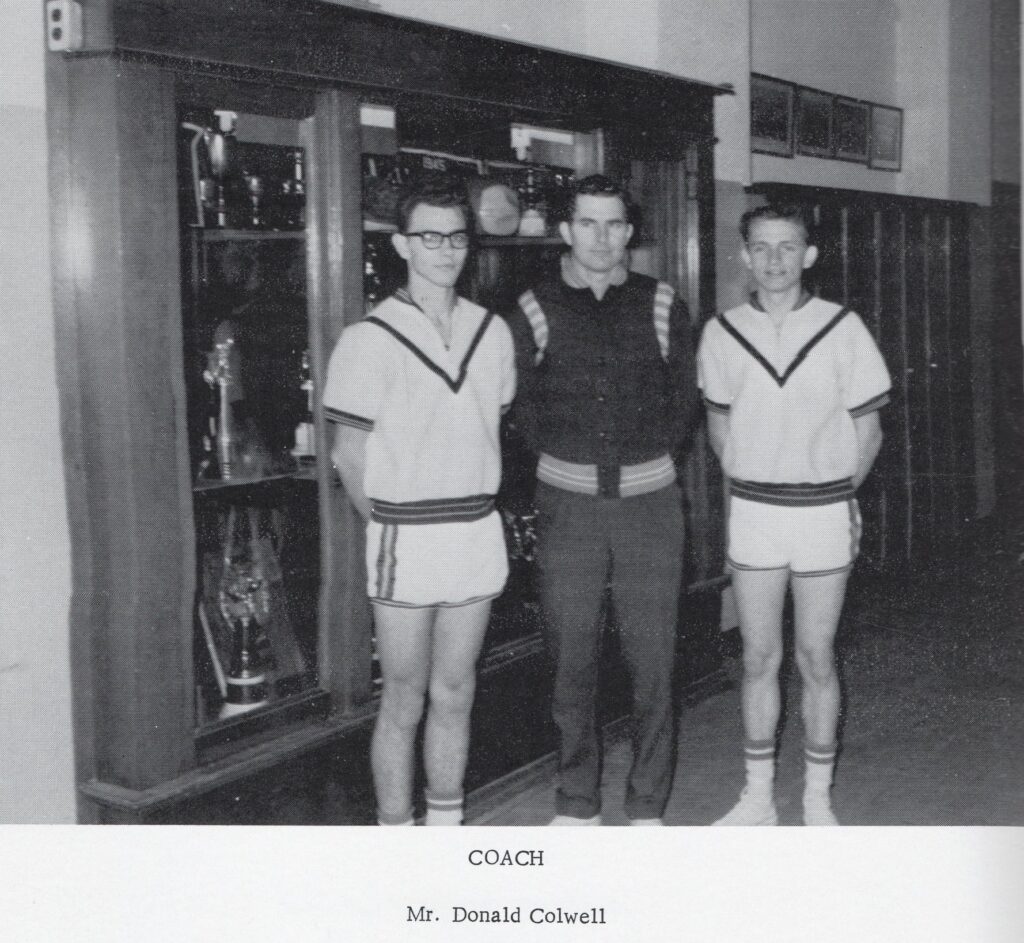

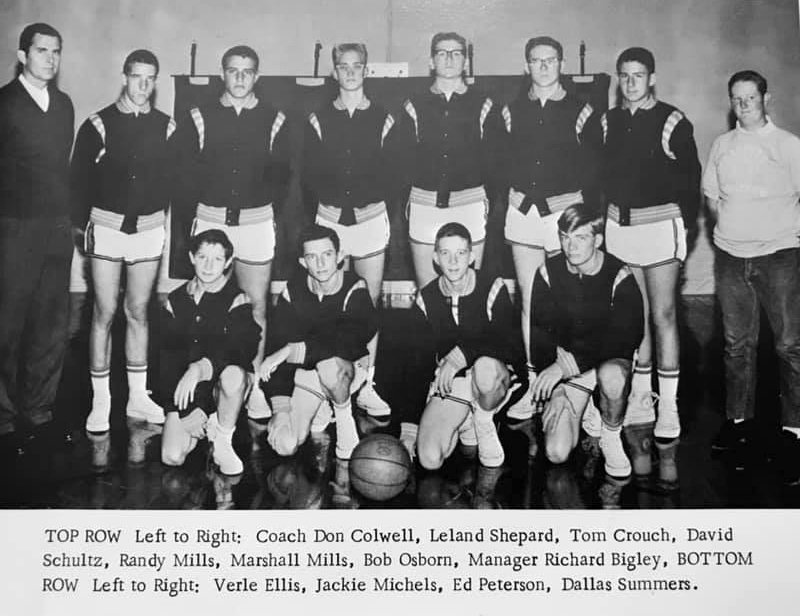

Bluford High School players were staggering down the stairs to the locker room to take showers when our coach, Don Colwell, unexpectedly called us back to the gym floor. Mr. Colwell, a tall handsome man with dark wavy hair and a deep resonate voice that sounded like it was coming from a deep well, instructed us to come back upstairs and sit at the center of the gym floor in a semi-circle.

We were dead-tired, all of us out of shape from the long summer layoff, our proud summer tans, gained by brutal work in the hay fields, just beginning to fade away. We plopped down on the gym floor, crossing our legs Indian fashion, our blotched, red faces betraying both irritation and curiosity. Once we grew relatively quiet, Coach Colwell moved to the middle of the u-shape we had made.

“I give this talk every year,” the coach began. “I don’t think anyone here will have this problem but just in case.”

Mr. Colwell paused and crossed his arms. All whispering, all squirming stopped. I bent forward to listen, my head cocked to one side.

“What I’m about to tell you was told to me by my high school coach, and nothing about what I’m going to say now has changed one bit. Do not, I repeat, do not get involved with a girl during the basketball season. I have lost a few very good players over the years who got involved with a girl and then quit the team,” he said. “It was a shame.”

That was it. As the coach walked away, we players looked around at each other, me raising my shoulders in a shrug, as if to say “duh.” I could not begin to imagine any of us giving up playing basketball for a girlfriend.

******

A week after the brief no dating speech, Coach Colwell divided the guys who had gone out for junior varsity into two teams and we began scrimmaging. The pool was almost equally divided between sophomores and freshmen. I was surprised how hard I worked in practice, scared in fact when I realized how badly I wanted to do well. But I faced a big hurdle, being from a tiny country grade school with just seven in my eighth grade graduating class, while the Bluford Grade School kids had already been playing together, having already forged a great squad. Just as worrisome, no one else knew my efforts were grounded in a non-athletic circumstance.

The rural area of southern Illinois where I was raised prized teenage males who could drive and fix farm equipment. I was not particularly good at either, and my stronger hay-hauling abilities were at the bottom of the status list of respected young farm hand skills. Playing basketball in high school in southern Illinois in the 1960s, however, was a big deal. I knew if I could make the junior varsity team as a freshman, my status would change. I did not know, however, that I was going to fall in love with the game.

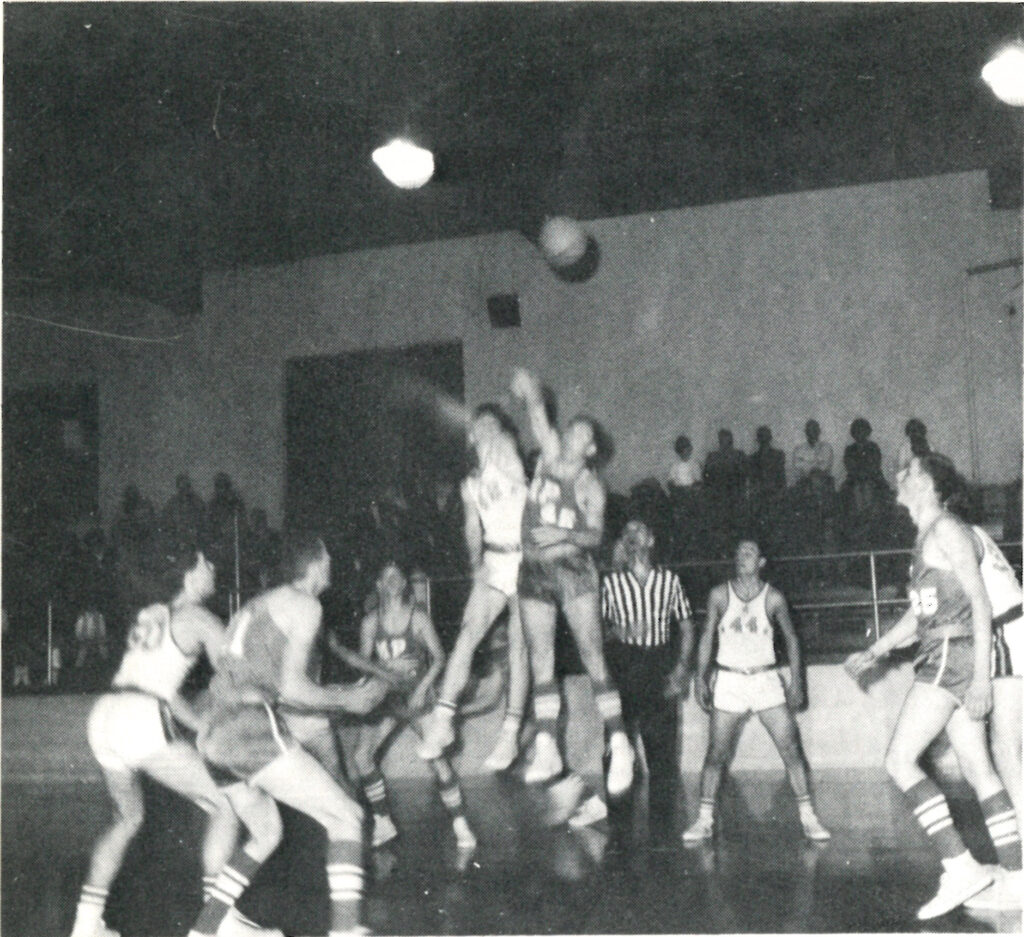

The sensory environment in practices was sometimes intoxicating— the soft indirect light that filtered through a row of opaque windows like mist at the very top level of the bleachers, the sounds of gym shoes squeaking on the wooden floor when players made a sharp cut, the feel of hard-earned sweat in the wintertime, the smell and texture of the resin we put on our hands to keep them dry. As the scrimmages continued, I was matched up with four of the best players, Bluford town boys, all of them fellow freshmen. This unexpected situation made me work even harder. I listened to the coach’s instructions. And I figured out a role for myself that seemed to be absent in the otherwise smooth execution of the four other guys, that of a big man filling up the center, blocking shots and grabbing rebounds. With my four team mates’ superb ball handling, scoring, and passing skills, I was set up to score some too. And there was always the few put backs I got under the offensive basket, garbage shots we called them, achieved with my long arms.

This was a new and exciting time for me, to be part of a five-man squad that came storming down the floor, executed a play with precision and then dropped back on defense until we got the ball back again and repeated the scoring process. It was simply exhilarating to play a lengthy duration of fluid almost flawless basketball in those otherwise long, sometimes tedious, practices.

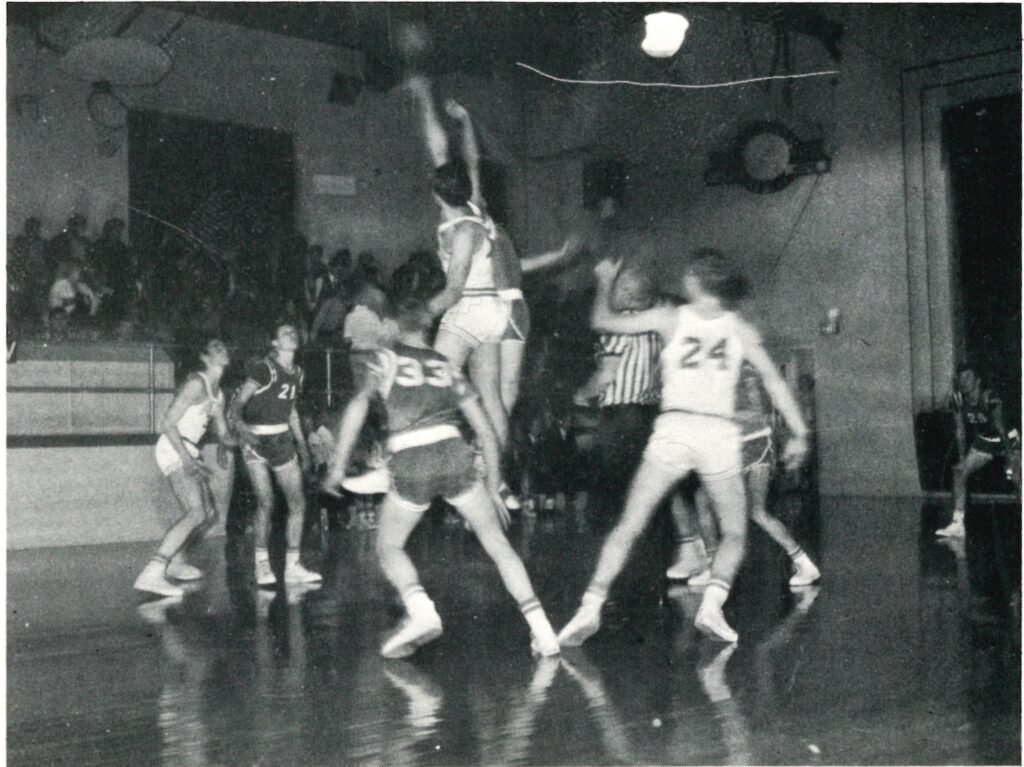

I soon discovered game time was even better. Instead of the fields where farmers had shaken their heads when I goofed up, there were the gymnasiums where my fellow starting team mates and I performed. Most often they were older gyms, some so small we called them cracker boxes. To me, all of them suddenly became sacred cathedrals, open and cavernous, the wood floors possessing a rich brown polish that seemed to glow with its own inner light.

An unexpected perk from my starting on the JV squad was that it drew my father and me closer together. Dad was often quiet and moody, but once I started playing basketball, he came to all my games. After each contest we’d talk in detail about how the game played out and what I might work on to improve my performances. Mr. Colwell was excited about our season too, although he kept a lid on his excitement. Always a cautious man, and perhaps not wishing to stoke any hubris, Coach Colwell waited to the end of the season to point out that we won our games against other junior varsity teams whose players were almost always older than us. It was his way of saying great things lay in store for him and our team.

On the down side that year, the varsity team Mr. Colwell also coached won only four regular season games, a couple of the better players quitting during the middle of the year to spend more time with their girlfriends.

Here it was, the very curse coach warned us about. The event brought forth yet another lecture from the Coach Colwell, a more serious talk with both the varsity and junior varsity squads present. Of course coach didn’t have to worry about me. As he gave his no-dating talk again, this time wagging a finger our way like a pistol barrel, I shut his voice out and thought about what it might be like to dress for the varsity the next year.

******

Late in the summer, before the beginning of my sophomore year, a great shock was delivered just after I came into the house from a hay field job. As I set down in a kitchen chair and gratefully pulled off my work boots and rubbed at my tired feet, Dad announced that Coach Colwell had decided to give up the coaching aspect of his job, wishing go spent more time with his growing family.

I was stunned and didn’t know what to think. Dad, however, was so worried, fidgeting around with his pipe all the time at the dinner table and asking me all sorts of questions about the upcoming season that his concerns finally flowed down on me, keeping me on edge until the first few days of my sophomore year in September of 1966.

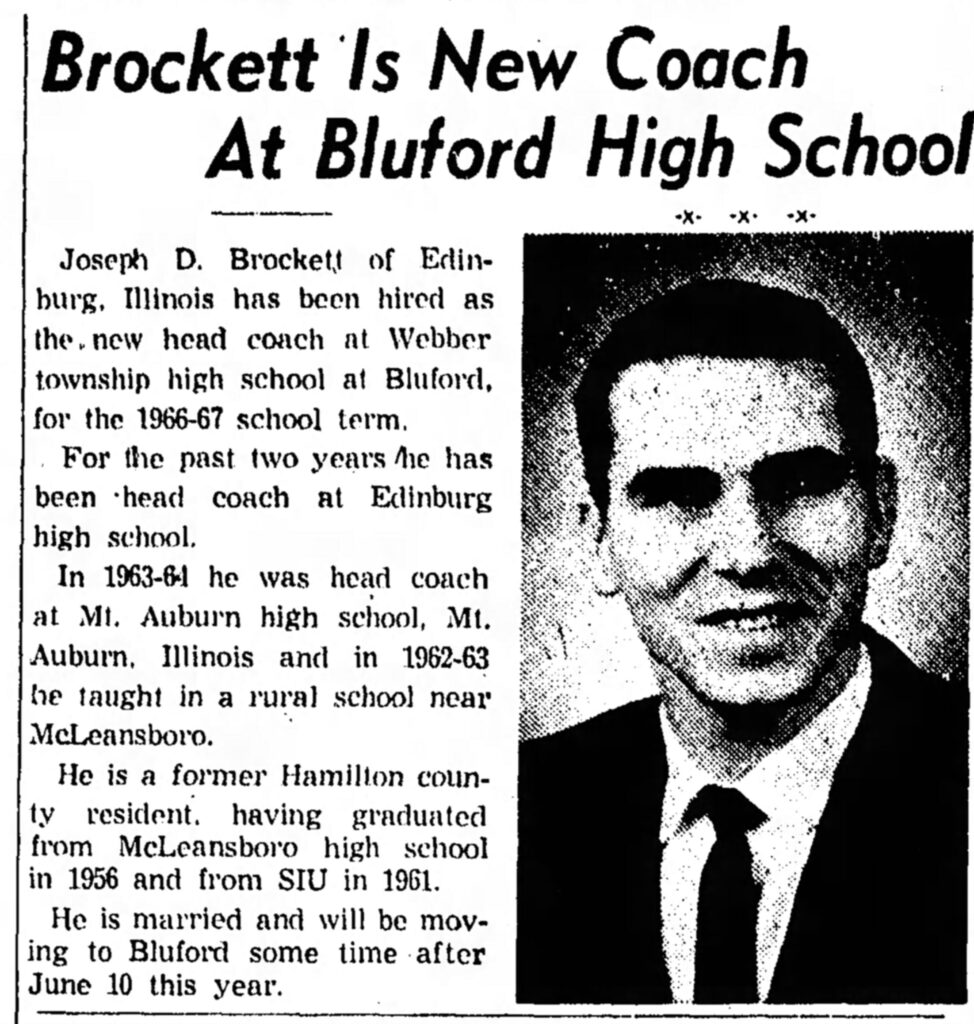

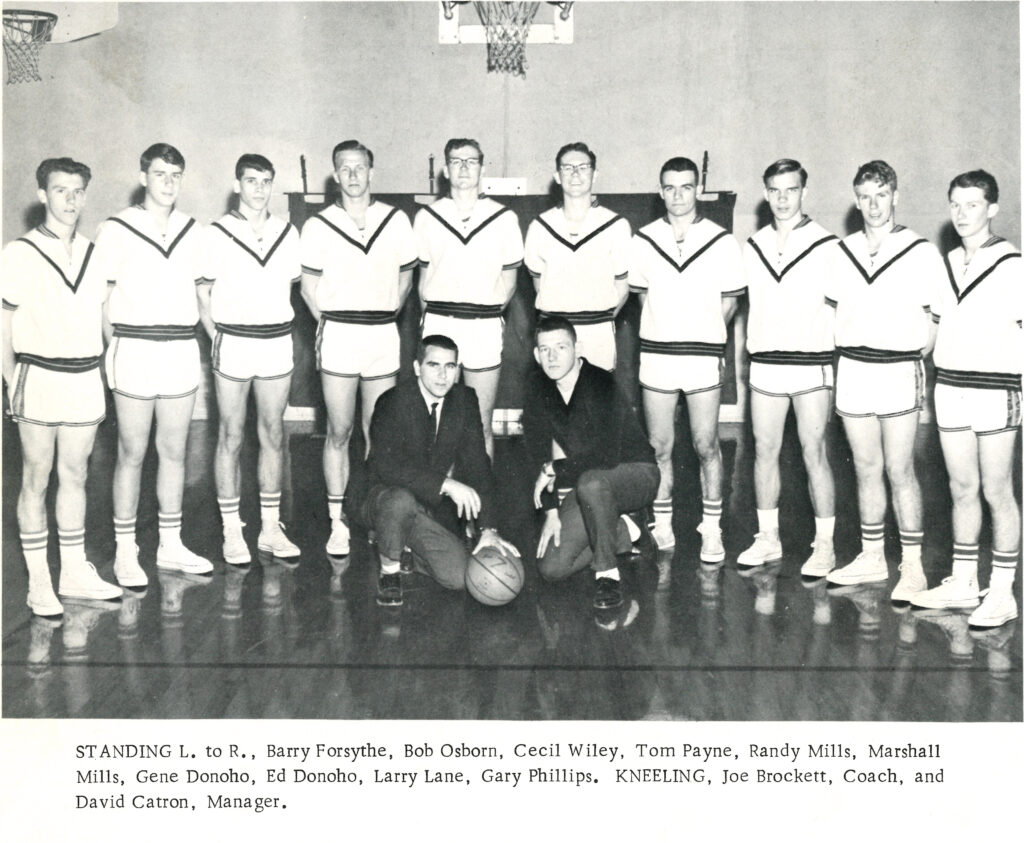

No one seemed to know much about our new coach, Joe Brockett. He was twenty-eight years old and had coached at two other small schools in the central part of the state, having a 5-17 record at the last school where he taught and coached. We players did know, however, that the new coach had no idea about the structure we had forged and lived with during the season prior. All of us, especially the sophomores would be starting from scratch. I did not know it at the time either that I had finished my last growth spurt—some weight gain, along with another inch and a half of growth, leaving me just shy of 6-3. I now weighed 210 pounds.

The few returning juniors going out for the varsity team were of little competition for starting spots, so the first hurdle for us sophomores were the returning seniors going out for basketball. The six seniors were a tight group of players who made it known they would not tolerate the thought of any sophomores breaking in as a varsity starter. Coach Brockett, a short man with an afternoon five-o’clock shadow, knew none of this.

I hung around my fellow sophomores during the first conditioning practices, all of us sucking in air as we painfully pushed our complaisant summer bodies into shape. By the fifth practice session bad vibes permeated the gym. Players cursed under their breath, one slipping on the gym floor where drops of perspiration made the floor slick. Huddling in a corner, we sophomores all agreed it looked impossible for any of us to break the seniors’ hold on a varsity starting position.

That none of us sophomores would likely start varsity was fine with me. I hated confrontation and looked forward to playing with my fellow classmates again, repeating the success of the year before on the junior varsity level and waiting until next year for our time in the spotlight. We also figured some of us would be dressing out for varsity games anyway.

The first practices were similar to how Coach Colwell had operated—calisthenics and running. We received the “basketball players shouldn’t be dating” lecture, a talk I didn’t pay much attention to since it wasn’t applicable to me. I do remember it was given in a more solemn and forceful tone than Coach Colwell’s talk the year before, as if there was some sort of moral violation when a basketball player became interested in a girl during the season.

Coach Brockett had us scrimmaging in the last practice before our first game. Oddly, we still hadn’t been told who would start, making everyone restless and grumpy. During that practice, I went up hard for a rebound, landing on the floor, holding the ball in a vise-like grip over my head, two senior players lying flat at my feet. Coach Brockett blew his whistle and then shook his head in disbelief. At the end of practice, when he announced the starters for our first game, I was on the list.

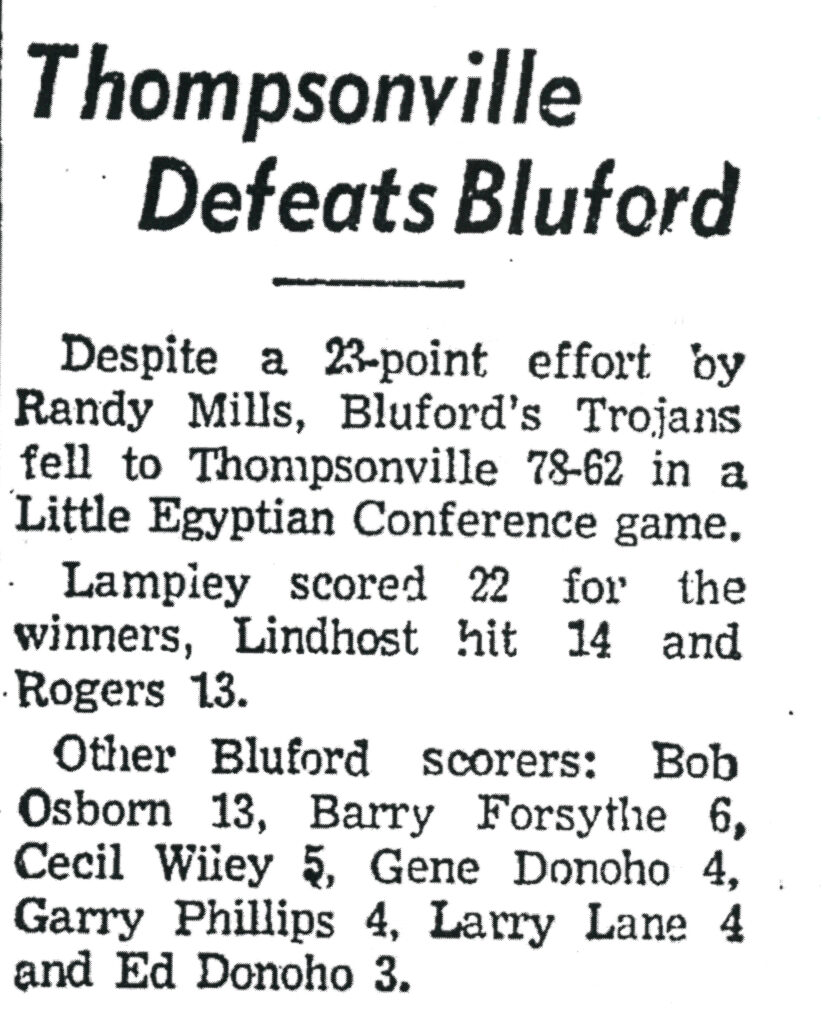

I did not know it at the time but my starting varsity the entire year as a sophomore would be my happiest time playing high school basketball. True, it took the seniors a while to let me into their playing circle, but when they saw how hard I worked and what I brought to the team, we got along just fine. I even became part of the scoring aspect of the game, being the leading scorer for our team in four contests and even making news in one sports article, John Rackaway of the Mt. Vernon Register News emphasizing my 23-point effort against Thompsonville in a Little Egyptian Conference game.

At some point that year, and for the first time in my life, I felt that I was making a contribution, that I was a part of something important and bigger than myself. The down side to the year was despite many very close games, we won only a single contest in the regular season, losing an important senior half-way through the season after he broke the oldest rule and quit the team.

By the end of the playing year, my self-esteem and confidence had grown by leaps and bounds. I also found myself being stopped and congratulated by an occasional neighboring farmer who had read about our team and my play in the newspaper. The best news, as I explained to my dad, was that the next year, when my fellow classmates would move up with me to the varsity level, we would have the makings of a very good team. My father’s response was surprisingly negative. “There will be bumps in the road ahead. You can bet on it.”

******

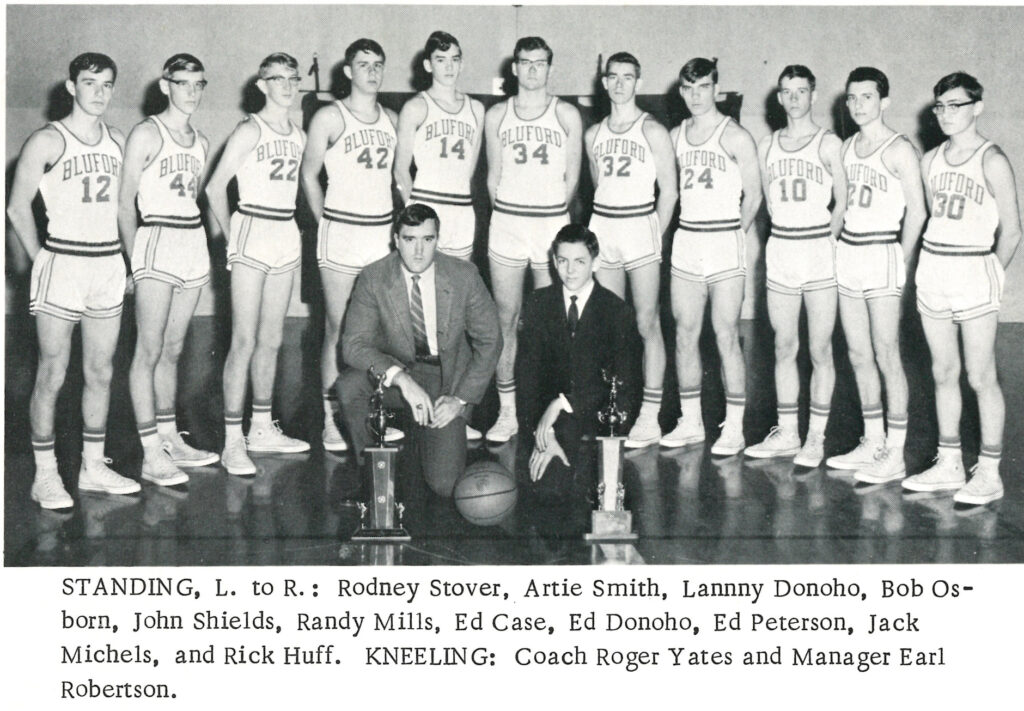

It wasn’t much of a surprise when Coach Brockett was let go and the Bluford team found itself with another new coach at the beginning of my junior year. While Coach Colwell and Coach Brockett had both been something of father figures, our new coach, Roger Yates, turned out to be more of an indulgent big brother who could administer a sharp reprimand if needed. Yates quickly saw how well we played together and was smart to build around our strengths. The team had three strong scorers—sophomores Ed Donoho and Ed Case, along with junior Bob Ed Osborn were all capable of knocking down twenty points or more on any given night. Jack Michels, another junior, and myself were expected to score in the lower double digit range.

Again we received the “no dating” talk, a very short conversation that Coach Yates ended with a wink.

We played an always strong Enfield team at our place in our first game of the 67-68 season. No one really knew what to expect. Before the game, Coach Yates was calm in the locker room, leaning his back against a wall and telling us, “Play a solid game, one we can built on in the future, whether we win or lose.”

As it turned out, we played almost flawless basketball, winning 66-63. Ed Case and I scored twenty points each to lead the scoring for Bluford.

Dad was shocked in a good way, chatting like a kid on the way home. The game hadn’t seemed easy or hard, just played like we performed all the time in practice. Sportswriter John Rackaway mostly emphasized Coach Yates’ former “prep star” status for the Mt. Vernon Rams in his next day’s report of our victory in the local sports page. He also got my first name wrong, calling me Bradley. Dad found a clipping in another newspaper, however, where I was labeled “rugged Randy Mills.”

Oddly, our success, including my unexpected point production, scared me. I knew the gods of basketball liked to even things out.

During the first half of the season, we swept past every opponent, going undefeated into the sixteen team Wayne City Holiday Tournament. Our fans were happily surprised, while sports reporters worked overtime to reassess their opinions about our team. After Bluford played four more games in the Wayne City tourney, I was Bluford’s number two scorer, a single average point behind our leading shooter. But there was no joy for me in this success. By then, I carried an unhappy secret.

******

Penelope Ann O’Neil was in the class ahead of me. Everyone called her Penny. My only awareness of her before my junior year was that her boyfriend, an exceptional basketball player who could jump out of the gym, had quit the team to spend more time with her. He had graduated the year before and at some point had given Penny a bottle of Chanel No. 5. It was this new and amazing fragrance that captured my attention the first day of a US Government/Current Events class taught by my favorite teacher, Mr. Cole.

Bluford High School did not have a cafeteria, so students had to bring their lunch and eat in the gym, go to a nearby little grocery/grill, Robinson’s Café, to buy a greasy but delicious hamburger and a bag of chips, or walk two blocks to Bluford Grade School and eat at their cafeteria. As fate would have it, I ended up doing the latter.

I followed Penny the first couple of times a few of us from high school walked over to the grade school cafeteria. By the third time, Penny and I were walking side by side, discussing the weather. In a husky voice, like Faye Dunaway’s, she told me she had gone to several basketball games my sophomore year and enjoyed seeing me play. I was happy too she did not bring up her boyfriend.

When the St. Louis Cardinals played in the World Series that October, the study hall teacher let our group walk over to the grade school to watch the final game on one of the grade school classroom televisions. The weather had turned sharply colder. Penny wore a new and stylish brown corduroy coat, the biting wind causing her to draw her chin deep into the new garment, dampening any conversation on our way over to the grade school.

After the game ended, on our way back to the high school, I drew close to Penny and slowly fastened up the top three buttons of her coat, feeling her breath against my face as I did.

Mr. Cole’s classes were more collegiate than most, with lots of informed discussions and group projects. Whenever we could, Penny and I chose to be in the same group. We’d get to class early so we’d have some time to talk or sometimes meet in the gym in the mornings before classes began, sitting and conversing on the top bleachers.

The somber discussions involving world and national problems that took place in Mr. Cole’s class colored our first few chats in the gym. While other students goofed around, Penny and I quietly pondered how bad the world seemed—the war in Vietnam, race riots, poverty. Penny said her favorite song was Jackie DeShannon’s “What the World Needs Now.”

Soon our topics changed. As students trudged through their gray mundane routines out in the hallway, Penny and I chatted happily away on the top row of bleachers, the immediate world around us as bright as Penny’s red nail polish. Nothing was said about the basketball season or world affairs. Instead, we talked about the latest school gossip, discussed movies we liked, and made each other laugh by telling funny little stories about our childhoods. It seemed we would no sooner start talking than the first class bell would ring.

One morning while sitting on the gym bleachers I told her how I liked going into old, abandoned farmhouses and about all the interesting things I’d found. She seemed intrigued. That weekend, a Saturday afternoon, she took me to such a broken-down place near her house. I was ecstatic. It was a bright sunny day in October and the fall foliage was spectacular. The house sat in a small grove of gnarled maple trees, whose leaves were so deep red and glowing, they seemed to be on fire. Surprisingly, she did not go in, telling me she was afraid there might be ghosts. I laughed and strolled in, but I was disappointed that she didn’t follow. I was hoping the spooky atmosphere would make her lean against me as we explored, maybe hold my hand.

She must have been on to something. I felt uneasy the moment I started walking through the junk-strewn rooms alone, the walls covered with moldy hanging strips of yellowed wallpaper.

I sensed the presence of something lurking in the ransacked house, a portent, perhaps, of sad things to come.

One morning in the gym Penny gave me a photo of herself as a little girl. This was just as everyone was leaving the gym to go to classes. I quickly tucked the black and white snapshot into a secret compartment of my billfold and then danced to geometry class, a subject I usually dreaded.

Some days, I thought of Penny O’Neil almost the entire time, and in my lack of control, I would have been the most miserable of creatures had I not been so mysteriously and totally smitten.

If Coach Yates ever thought me a little distracted, he didn’t say. Meanwhile, I’d watch through the two sets of double doors that served as the gym’s entryway during basketball practice, hoping to catch a glimpse of Penny walking through the hall, or stole glances up to the top tier of bleachers where we sat in the mornings before classes started. Sometimes, when I ran past one of the doors, chasing a loose basketball, I thought I caught whiffs of her perfume.

By mid-November, at the beginning of a basketball game, I was blissful and distracted, until I got into the flow of the contest, but no one seemed to notice. It was like walking a tightrope—with thinking about Penny all the time on one side and the excitement of the basketball season on the other.

******

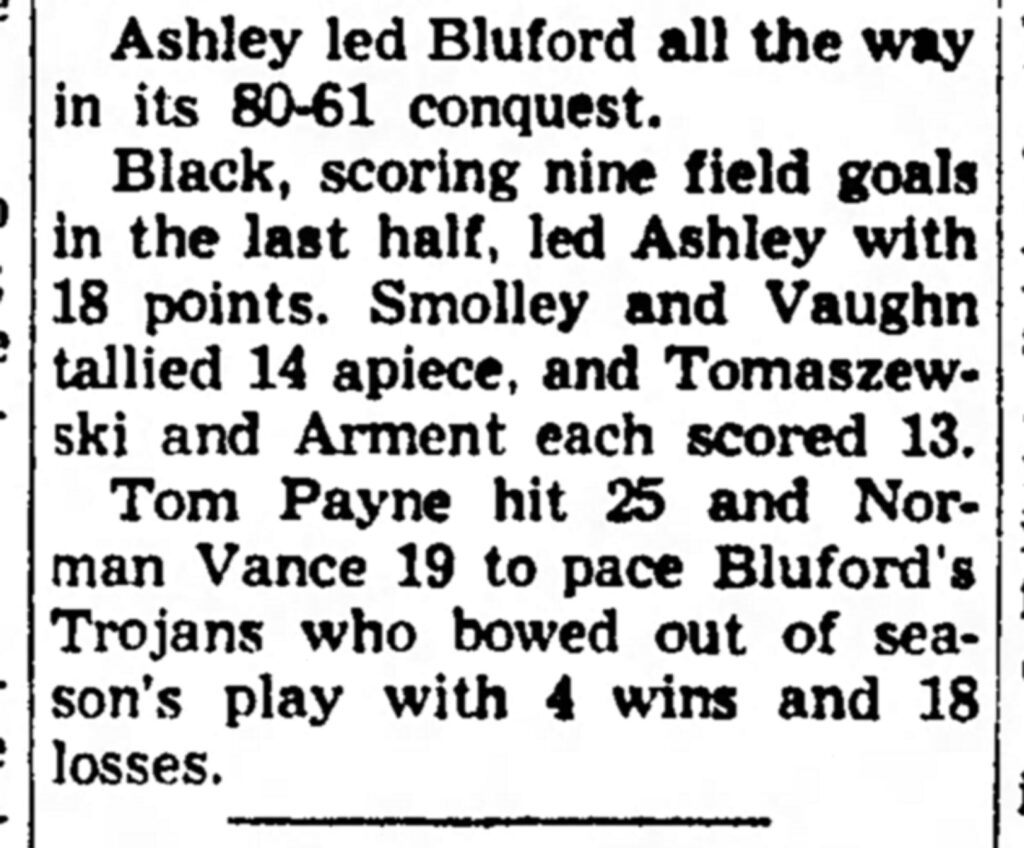

In spite of my love-lorn condition, Bluford kept on rolling. We beat conference foe Tamaroa for our seventh straight victory and were labeled “red-hot” by John Rackaway in the Register News. When we pounded Thompsonville 90-67 in the next contest, I must not have been too distracted by thinking of Penny. I scored twenty-one points that game.

As Christmas break came around and we prepared for the Wayne City Holiday Tournament, my world was perfectly but delicately balanced. I was away from the drudgery of school, Penny had told me she was looking forward to seeing the Bluford team play, and the Trojans were undefeated going into the tourney. Only Dad seemed to have any clue about my double life, asking me once at the breakfast table if I was seeing anybody. With my mouth full of Cheerios, I answered an emphatic “No!”

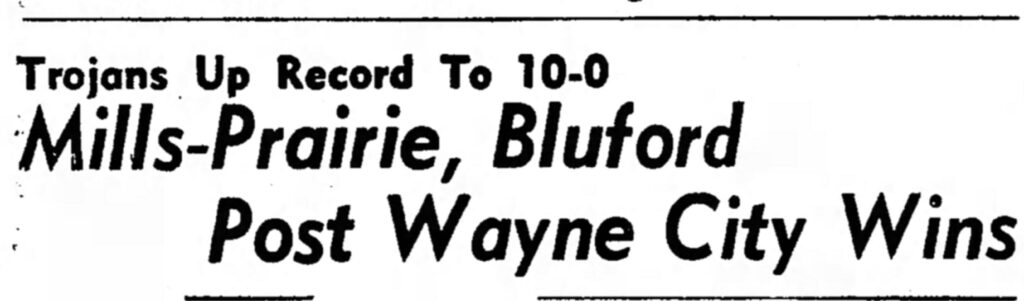

Sports columnist Merle Jones, in the Southern Illinoisan reported that the 1967 Wayne City Holiday Tournament had the best top four seeds in the tournament’s history. John Rackaway agreed, writing, “Wayne City’s 16-team field, probably the best in the thirteen tourney years, includes many of the strong small-school quintets in southern Illinois.” Mills Prairie was ranked first, followed by a very strong Sesser team. In spite of being the only undefeated team in the tourney, we were seeded third. Waltonville followed.

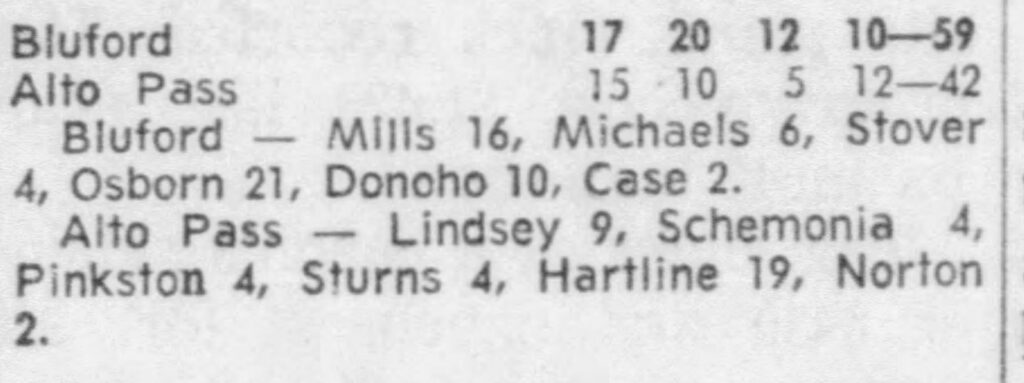

We faced Alto Pass in our first tournament contest. The first quarter of the game was a shocker, Alto Pass hanging close and only trailing by two points at the end of the period. In the second half, Bob Ed Osborn broke the game open with several long bombs, scoring twenty-one points altogether and we hardily won. I had sixteen points and probably would have had more if I hadn’t been looking up in the stands so often where the Bluford fans sat, looking for Penny.

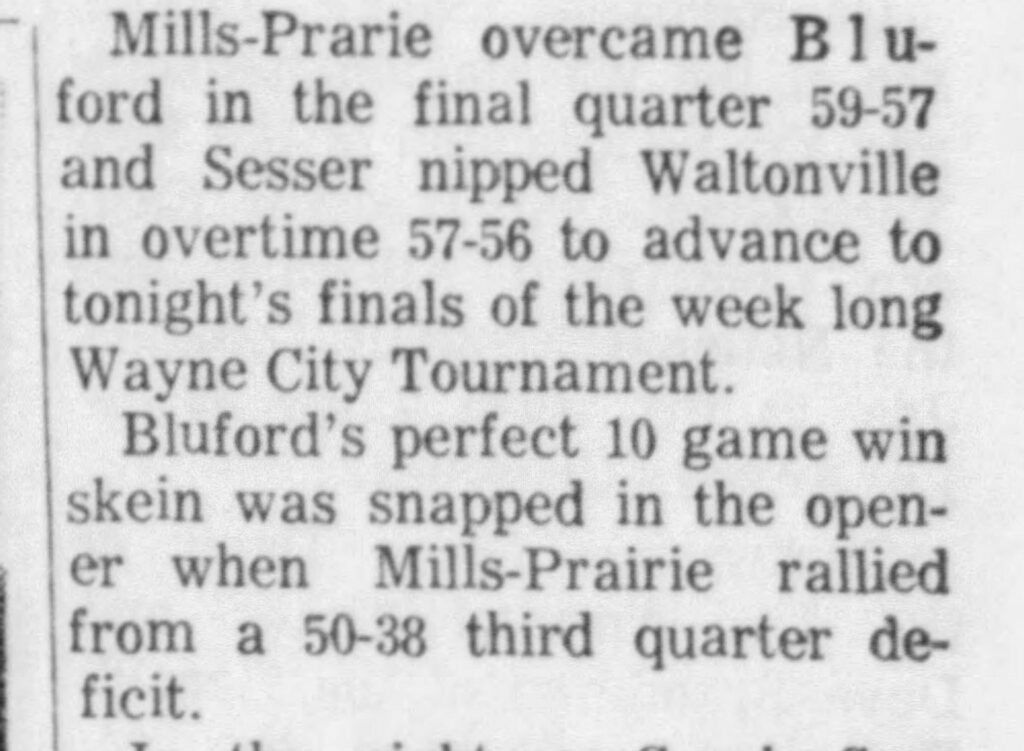

Wayne City blasted Christopher 81-57, to set up a next round game with us. We had barely beaten Wayne City earlier at our place, on Bob Osborn’s last second shot. Now we faced them on their home turf with what promised to be a sea of screaming Wayne City fans clad in red.

During the entire crucial Wayne City game, Coach Yates stood as straight and still as a statue on the sideline in front of our bench, his brawny arms crossed and his dark eyes locked on the action. The contest was close again, with Osborn leading Bluford to victory with nineteen points. The rest of our scoring production was evenly spread among five other players. Bluford led by two points at every quarter stop except for the final, winning 65-58.

No one could have known that Bluford had arrived at the pinnacle of its 67-68 season. I was too miffed after the Wayne City game, however, not seeing Penny in the stands with her plush brown coat at her side for a second game in a row to ponder much of anything. Now familiar waves of depression began lapping at the edges of my world.

We played top-ranked Mills Prairie in a semi-final game, exploding into a solid lead and adding to that lead every quarter up to the fourth, taking only good shots, making free throws, and hardly fouling. Not once did we throw the ball away. When the fourth quarter started, we held a solid 50-38 lead. We had Mills Prairie, had them cold. And then, inexplicably, victory slipped away.

Mills Prairie hadn’t even started pressing us when the first Bluford player lost the ball early in the fourth quarter, inadvertently kicking it out of bounds with a sickening thud. Mills Prairie quickly scored on the turnover, and on the next play, after we got the ball back, a Bluford player made a bad pass that flew out of bounds and into the stands, an elderly lady screaming as she ducked her head as the ball sped past.

Then Mills Prairie started pressing, and we couldn’t seem to get the ball up the court.

Suddenly, no Bluford player was exempt from mistakes and no one seemed to want the ball. Coach Yates called two timeouts to calm us down, patting our shoulders, telling us to play our game, but to no avail. Mills Prairie outscored us 21-7 the last quarter, scoring the last two points that won the game in the final seconds. Ed Donoho and I both had sixteen points each, but the scoring honors brought no joy.

The Mills Prairie game was the only complete breakdown the Bluford Trojans would have that season or the next, and would always remain a mystery as to its dynamics.

The next night, in the battle for third place, Waltonville made the mistake of leaving little Jack Michels open at the top of the key, daring him to take the shot. Michels took the dare, scoring a team high twenty-one points and getting several steals to lead Bluford over Waltonville 67-64. Sesser then beat Mills Prairie, winning the title match in overtime, 79-74.

******

Coming back from Christmas vacation, I entered a time of unexpected travail. I had mooned over not being able to talk with Penny during the long Christmas break, fantasizing about being with her while Christmas carols blared over the radio. Finally, I just incorporated the songs into my fantasies. I drove myself crazy, wondering if she possessed the same strong feelings for me. When school finally started, I tried to enjoy our reestablished early morning gym discussions. But the bliss had disappeared, replaced by a growing sadness, a fear that our relationship would somehow end, and that I would never be able to tell Penny how I felt. Worse still, I had no one to talk to about the problem. I spiraled down deeper into a dark gloom.

The day before the Ashley game, in the morning before school started, Penny and I were sitting in our usual spot in the gym, talking. In the middle of some light chatter, as I took in the aroma of her perfume, Penny announced that her boyfriend and she were going to get married in the early part of the spring. Somehow, I managed to keep an indifferent face, mindlessly nodding my head as she moved on to another topic, something about some new top forty song. I didn’t hear a word she said. All this time I had harbored hope that Penny’s feeling for me had grown to the same degree that mine had for her. In fairness to Penny, I had never once hinted about my feelings and possessed absolutely no plan for what I would have done if she had ever announced such feelings for me. It was surely the most miserable place for a naive teenage boy to be.

The rest of the playing year was more than decent for the team. I, however, never regained the scoring level that I achieved in the first half of the season, ending at a twelve-point a game pace. Luckily, my shot-blocking and rebounding production remained steady.

When state tournament time rolled around, Bluford won the district championship and then upset Sesser in the first round of regional play, the latter victory somewhat redemptive, given Sesser had won the Wayne City Holiday tourney earlier that season. After the Sesser win, Merle Jones at Carbondale’s Southern Illinoisan noted, “Bluford played with much more poise and skill than a lot of the big schools I have seen this year.” Benton, however, brought us back down to earth in the second game of the regional.

Once basketball season ended, gloom ruled my day. Dad returned to his moody self and there was a rumor that Woodlawn had offered Coach Yates a coaching job at a much higher salary. Penny was unavailable to talk with, and trying to do school work became dry and boring, like trying to swallow sawdust.

One spring evening, towards the end of school year, I sneaked into the high school gymnasium. I sat in the center circle, completely alone, trying to get some clarity to my life, keeping my back to the side of the gym where Penny and I had, for a time, met daily in the bleachers.

The old gym wasn’t completely dark, more like under water that first foot or so in a farmer’s pond, where things were murky but still see-able, a perfect environment for meditation. In that quiet semi-darkness, the sound of a creaking gym door suddenly broke the spell. I jumped up and ran into the deeper shadow of the opening to the stairway that led to the boys’ locker room.

The interloper turned out to be the school’s janitor, Mr. Brookman. I could not quite make out his facial features but the lanky, lose-jointed silhouette could only be his. His eyes were cast down as he stood there with a wide janitor’s broom. Thankfully, he did not see me. I don’t know how I would have even begun to explain to him what I was doing there in the middle of the high school gymnasium with not a single light on.

Propping up the broom handle against his chest, Mr. Brookman lit a cigarette, then began pushing the broom back and forth across the floor. He moved as slow as a sleepwalker, the tiniest pinpoint of fiery red, flaring in the darkness whenever he inhaled.

I ducked out the building, more depressed than ever.

In May, Bob Osborn’s parents gave the Bluford team and the cheerleaders a post basketball season party in their fixed-up basement. It started out as a good time. Mr. Osborn gave a little talk about what we had accomplished, noting that the team had gone from a one regular season win the year before to a twenty game winning season. We were champions of the Little Egyptian Conference, the first conference title ever for Bluford. The team also captured the district tournament championship, an accomplishment Bluford had not been able to achieve in over a decade. And there was our third place finish in the big holiday tourney.

The polished trophies for our accomplishments were displayed on a cloth-covered table. There was music, good food, and a pool table. We players, a bit awkward in this non-athletic setting, talked in small groups about the season, especially the funny things that had happened in the locker rooms and on the court. At some point, one of the cheerleaders came over and sat on my lap, but her thinness only reminded me of Penny’s voluptuousness, of the day we had sat close together in the gym bleachers before school started.

******

The last week of school seniors did not have to go to classes, so I was surprised to see Penny approaching me in the hallway, a yearbook in her hand. “Please sign this,” she said.

I did write a short line or two, the best-of-luck stuff that fills every high school yearbook on the face of the earth, then handed it back to her.

“Now yours,” she prompted.

I went to my locker and pulled out my yearbook and handed it to her.

She took her time writing, her bright little tongue hanging a bit from one side of her mouth, as if she were threading a needle. I did not give her the satisfaction of seeing me read what she wrote.

“Gotta go to class,” I said.

No scholar ever pored over a set of words the way I did Penny’s entry in my yearbook. Was it possible I’d misinterpreted the feelings I thought she had for me? I spent months rereading what she had written, stepping back so many times through those words my tracks would have worn a path through the Bluford gym floor, until I grew weary of the endeavor and put the yearbook away to collect dust.