While working on a book about Larry Bird’s high school basketball experiences, I became fascinated with what happened to Larry the year after he graduated from Springs Valley High School, his dropping out of IU and especially his short time as a basketball player at Northwood Institute in West Baden, Indiana. On first glance, there seems hardly a trace of a story about Larry’s time at Northwood and what few narratives are out there often conflict and vary. Larry’s own brief statement about the episode in his book Drive simply seems to shortchange the reality of that time and place. “I don’t think I lasted two weeks. I practiced with them a couple of days before realizing there wasn’t enough competition, and I didn’t belong there either.”

But I sensed there was more to the story. I began looking at old newspaper accounts, reexamining the brief narratives already out there, and taking fresh interviews, finally putting together a more detailed story about that difficult and mostly forgotten time in Larry Bird’s life. Perhaps the greatest find in this research was the only photo of Larry in some kind of Northwood uniform, in this case a Northwood warm up jacket.

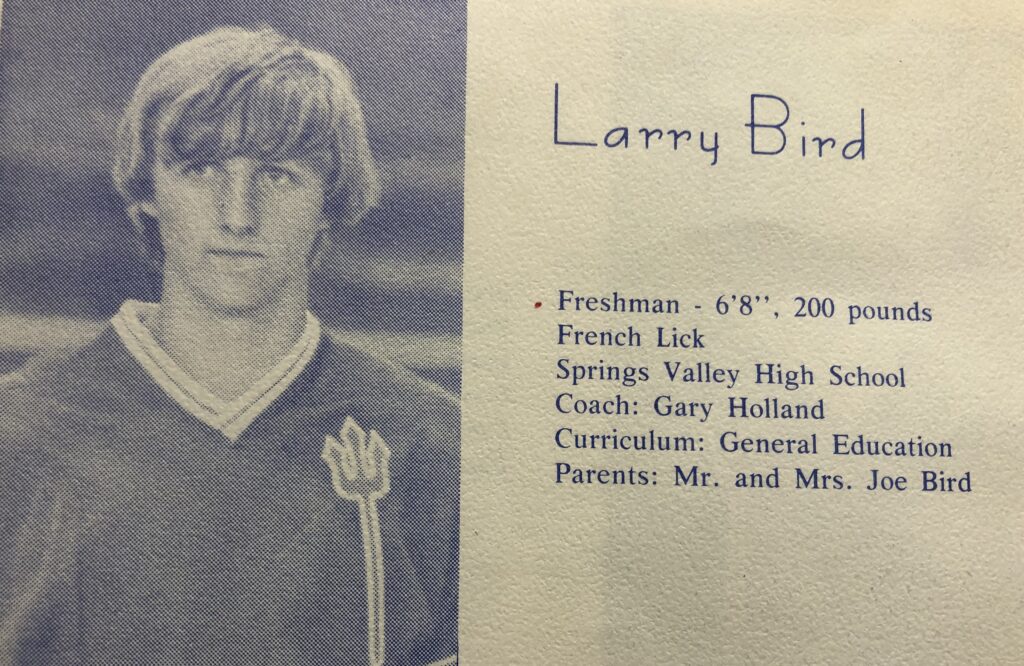

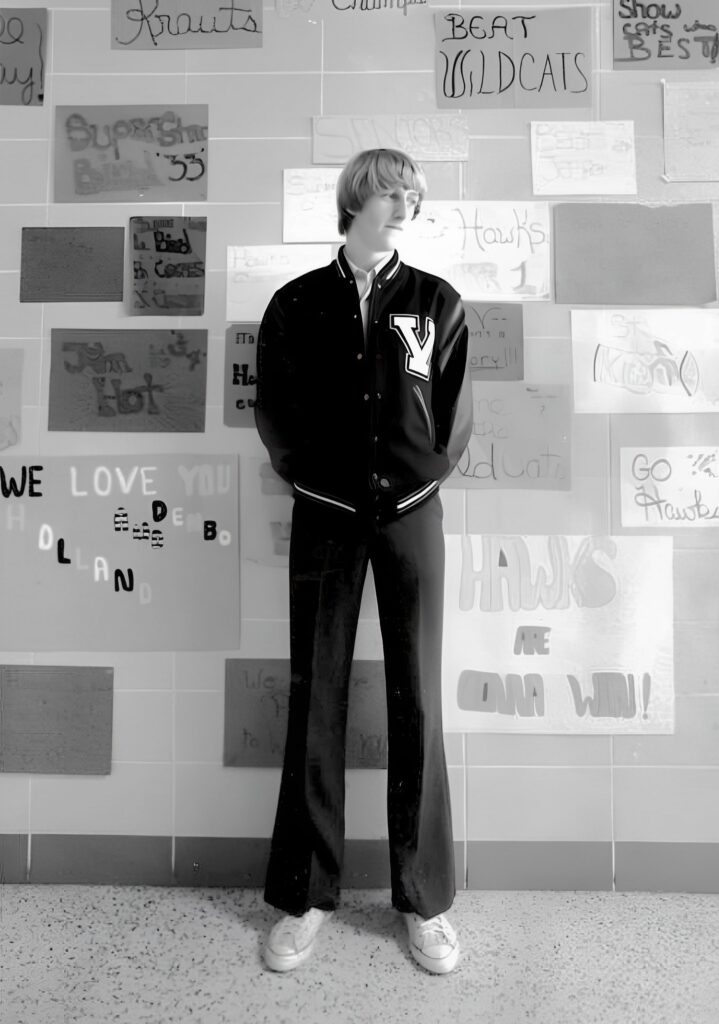

Any understanding of Larry’s Northwood experience must be framed by an essential bit of back story, one that begins at an exciting high point in Larry’s life. Two photos capture these moments, the first taken towards the end of his senior year. In this photo, snapped just before the Springs Valley Blackhawks were to face the Jasper Wildcats in Washington regional play in 1974, Larry is standing before a wall in the high school hallway, the wall decorated with signs wishing Larry and his teammates luck in the upcoming game against the “Krauts” as the Jasper team was sometimes called in those days before political correctness. Larry is staring into the distance to his left, reflecting perhaps on the just passed regular season successes, on winning a sectional tourney, and on the hope of advancing deep into state tournament play.

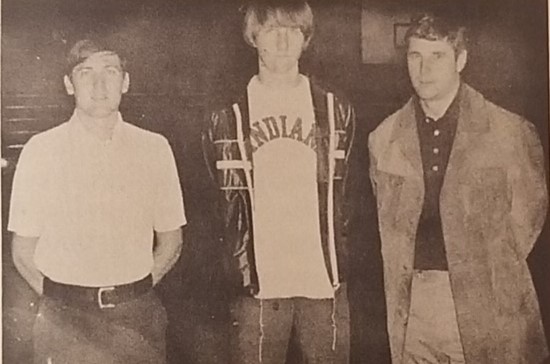

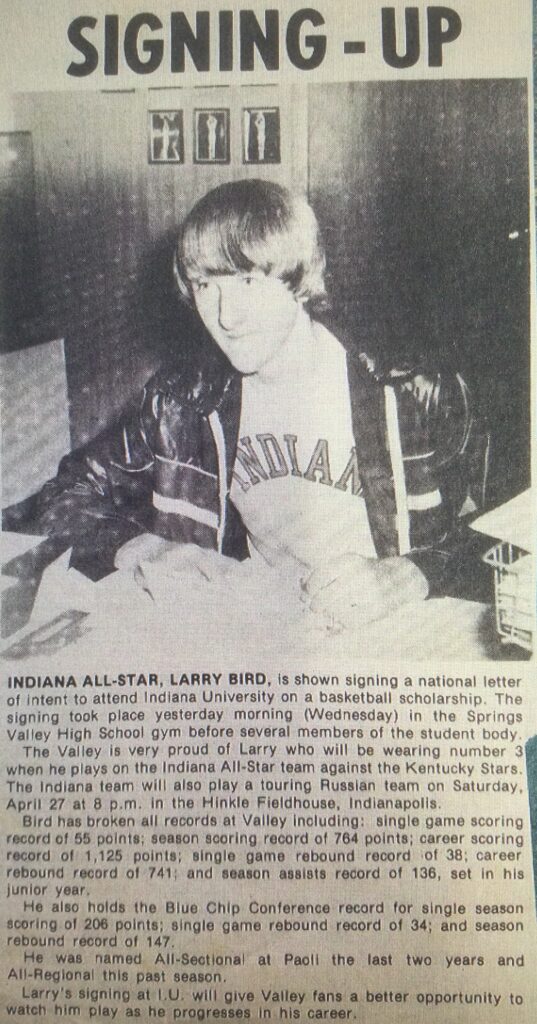

The second photo was taken a couple of months later. In late April of 1974, Bob Knight traveled from Bloomington to Springs Valley High School, and Larry officially signed papers to attend IU. Outsiders could only believe Bird was on top of the world, although in a newspaper picture of Coach Holland, Larry Bird, and Coach Knight after the signing, Larry’s face revealed no emotion. A local sportswriter certainly captured the excitement of the community, their longing for Larry to continue to represent the towns of French Lick and West Baden with his exciting basketball skills. After listing Bird’s many amazing accomplishments in just his two years of varsity play for the Blackhawks, the reporter noted, “Larry’s signing at I. U. will give Valley fans a better opportunity to watch him play as he progresses in his career.”

Since the Bird family lacked a car, Larry’s Uncle Amon Kerns drove Bird the fifty or so miles to Bloomington late that summer, leaving him in a dorm room with perhaps a quick and uncomfortable goodbye. Larry, an unsophisticated seventeen-year-old who was exceptionally shy around strangers, now found himself sitting in a small unadorned room in a world that was as strange to Larry as another planet.

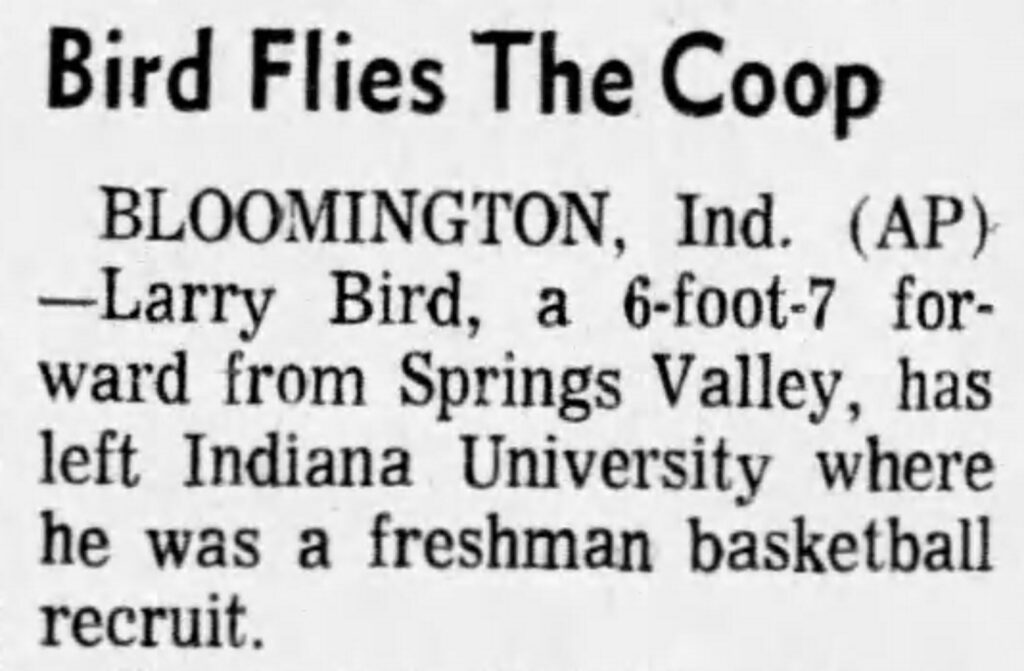

Larry lasted less than a month at IU, returning home to be greeted by a storm of disappointment and, in some cases, even anger. Of course, the French Lick/West Baden communities were completely unaware of their hero’s struggles at Indiana University. Larry, always one to hold his cards close to his vest, didn’t let anyone know he was coming home and just showed up unannounced, this only adding to the confusion. In Drive, Larry told how his family “was upset, and the townspeople were shocked.” Part of the blow to his family and the community sprung from the feeling Larry had given up too soon. “It was considered a great honor to play for Indiana University,” Larry recalled, and at first the community, thinking Bird had just made a rash decision, tried to talk Larry “into going back.” A shaken Amon Kerns even offered to take his nephew back to Bloomington, but Larry responded with a defiant “No!” to the offer. As time passed, and no explanation was forthcoming from Larry regarding what happened, locals grew more disgruntled.

In truth, while Larry’s family and the community believed Larry was misguided and wrong about leaving school, Larry, before he left IU, had worked hard to face uncomfortable realities about his personal and financial limitations and, in the process, gained an understanding of what he needed to do next. In short, the seventeen-year-old Bird, perhaps for the first time, was beginning to make important adult decisions based on his understanding of who he was and what he wanted to do with his life. As he noted in his autobiography about leaving Indiana University, “That was the first extremely important decision I had ever made for myself, and I was sticking to it. I knew that everyone would be angry with me when I made it and that there would be a lot of pressure on me when I got back, but I didn’t care.”

Also, Larry had not given up on playing college basketball, but he likely realized while at IU that a large flagship school such as Indiana was not a place where he would be most successful. He perhaps knew too that he still needed to figure out what he must do to operate in a college setting. Clearly, this meant going to a smaller school, likely Indiana State. Larry also came to understand that he needed to make some money so he would not be taking funds from his mother, money that could be used for other important financial family burdens. “I had no money—and I mean no money. I had virtually no clothes,” Larry explained in Drive. Larry’s IU roommate, Jim Wisman, had been quick to offer to share clothes and loan money, but Larry wasn’t comfortable doing much borrowing. Bird also understood he likely needed time to heal. “I just knew it was going to help me—mentally and financially— to sit out that year.” Larry may have looked at this time off from playing college basketball as his “red shirt” year. Other writers have called it Larry’s “lost year” and his “year off.” However, there would be a definite bump in the road.

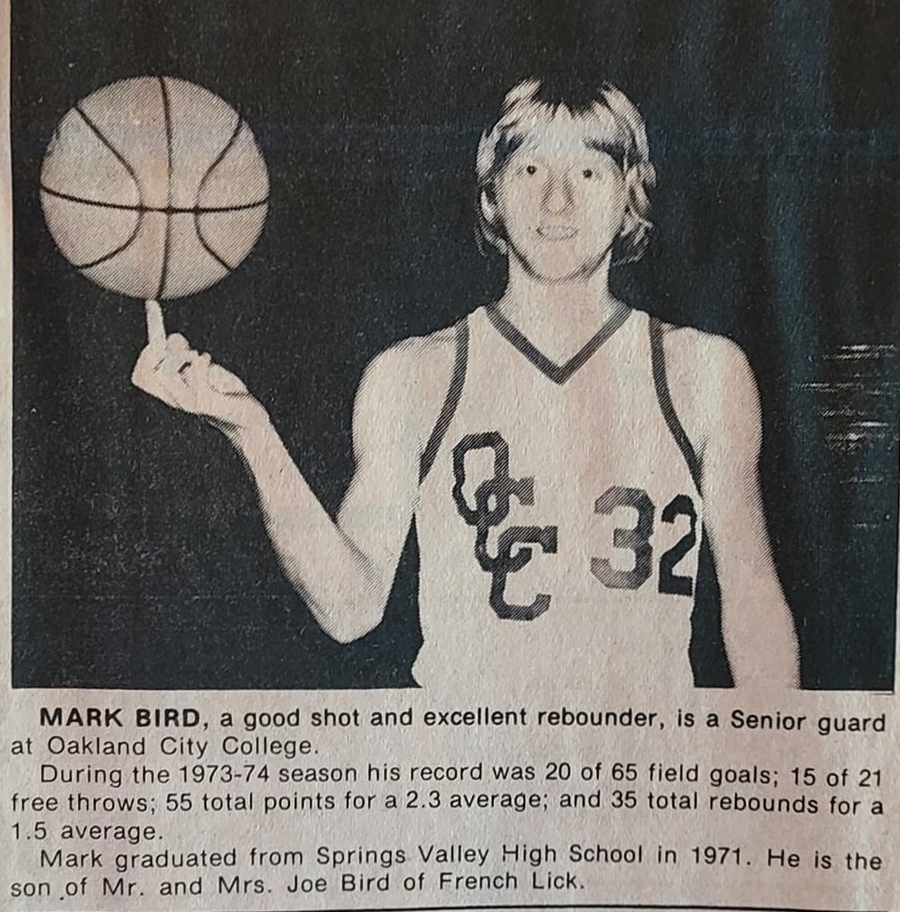

Bird got a taste his family’s sore mood about his dropping out of IU shortly after he returned from Bloomington to French Lick. He and a friend decided to go and see Larry’s brother, Mark Bird, play in the first game of his senior year at Oakland City College. When Larry arrived at the gym in Oakland City, Larry’s parents were already there. “Dad started talking to me,” Larry remembered, “but Mom wouldn’t say a word.” Georgia was so mad at her son, she barely talked to him for a month.

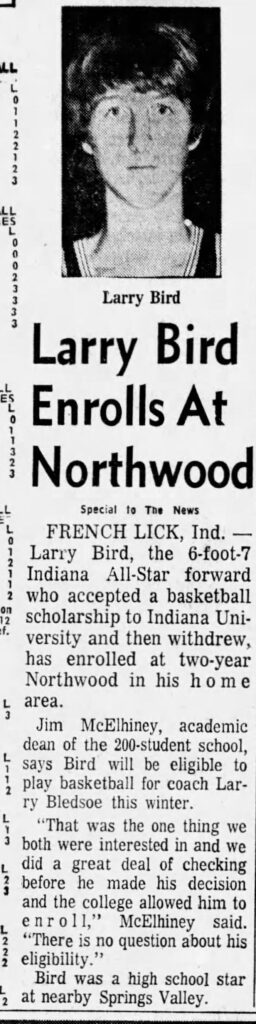

It was at this point that Larry’s Uncle Amon Kerns stepped back into the picture with a plan for getting Larry into a college again, playing basketball, and bringing peace between the Valley community and the IU dropout. This time Larry complied, noting in Drive, “Despite leaving IU, I still needed to play basketball. I came back home, and people were after me to go to Northwood Institute, which was right there in West Baden. The next thing you know, I was enrolled there.”

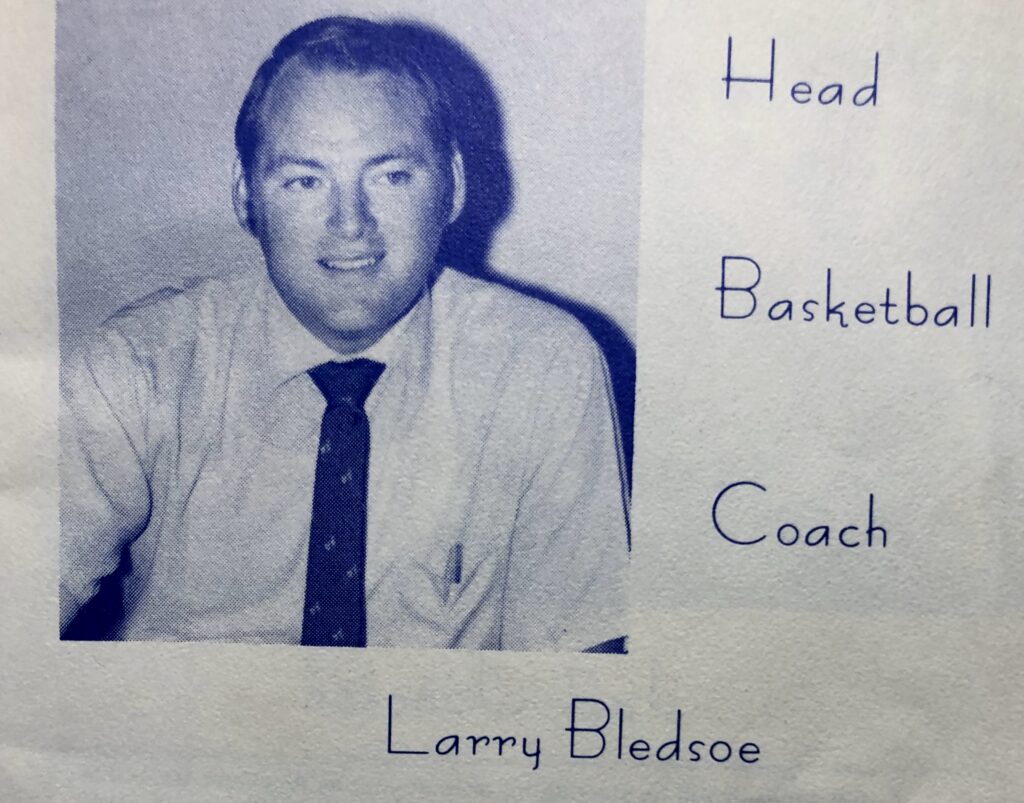

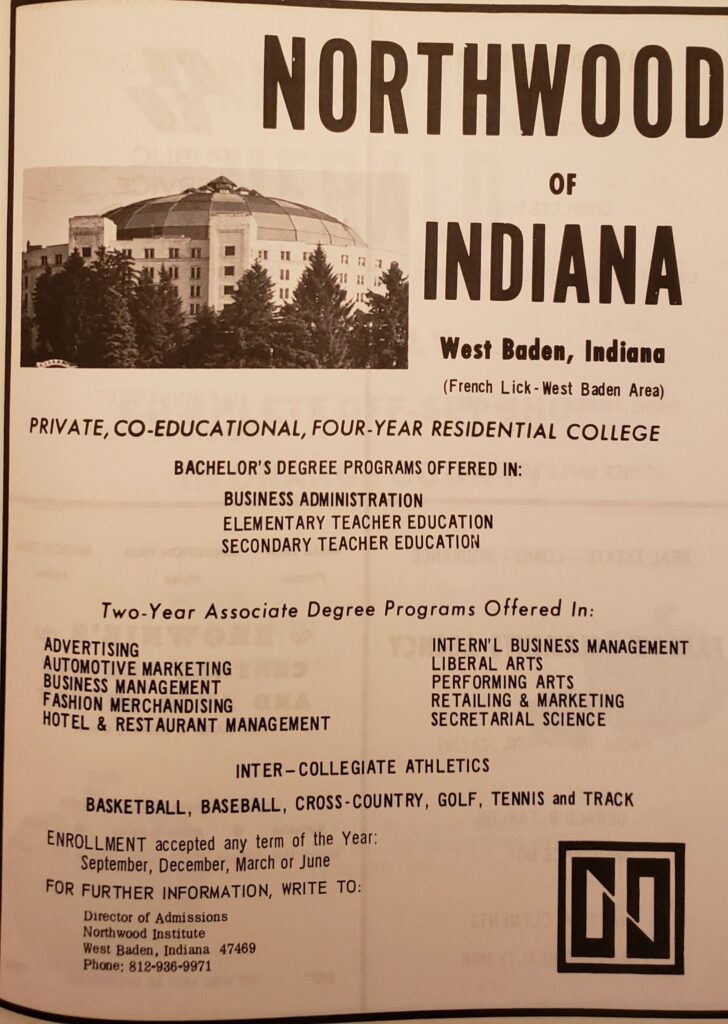

The ball had started rolling when Amon Kerns called a friend, Northwood basketball Coach Larry Bledsoe, to see if Larry might be able to play for the Blue Devil team. Kerns brought Larry to the campus, where the Northwood coach explained there wasn’t any money at that point for a scholarship. Kerns insisted Larry wanted to play for the team anyway and that Larry could stay with his family. (Larry was then staying with his grandmother Kerns.) But Coach Bledsoe later recalled that the talk did not seem quite right, that the young man seemed uncomfortable, and that his uncle did all the talking. Bledsoe, for his part, was likely taken aback. The year before, the Blue Devil team had achieved an unimpressive 11-16 record while playing smaller four-year schools like Oakland City College where Mark Bird played. Furthermore, in the 1974-1975 school year, Northwood Institute would be moving from four-year status to becoming a two-year junior college and playing even lesser competition. Coach Bledsoe just figured the school’s basketball program would not offer Bird enough competition. But of course, he still quickly said yes to the request.

Larry may have relented and initially gone to Northwood because he would be accomplishing several things by joining the Blue Devil team—acclimating himself to college studies in a more manageable environment after being overwhelmed at IU, keeping his hand in basketball and letting other four-year schools know he was still in the recruiting mix, and pleasing his family and the community after his returning home from Indiana University. Concerning the latter aspect, Lee Levine, one of Bird’s biographers, pointed out that the community pressure on Larry was all but unbearable. “The Valley had been living vicariously through Larry ever since he’d started to be a basketball success. When Bobby Knight had recruited Larry, it was almost as if he had been recruiting the community itself.”

The news in Indiana newspapers of Larry’s coming to Northwood Institute hit with a bit of a pop, with almost every sports page in the state noting and discussing the event. Lafayette’s Journal and Courier playfully headlined “Indiana Bird Finds New Nest” while the Munster Times declared, “Bird Finds Home.” The Kokomo Tribune captured an important feature involving Bird’s decision in their headline, one that suggested why Larry chose this small, little-known school—“Bird to Attend Hometown College.”The Indianapolis News emphasized how small Northwood was, having just 200 students, but also pointed out Larry would be close to home. There was even an out-of-state report on the event, the Louisville Courier-Journal headlining, “All-Star Bird Boosts Northwood’s hopes.” Al Brewster, a sportswriter at the more local Bedford Times-Herald, may have offered the most astute assessment about Larry’s surprising decision, asserting that with Larry’s enrollment at Northwood, there would be “singing in the Valley.”

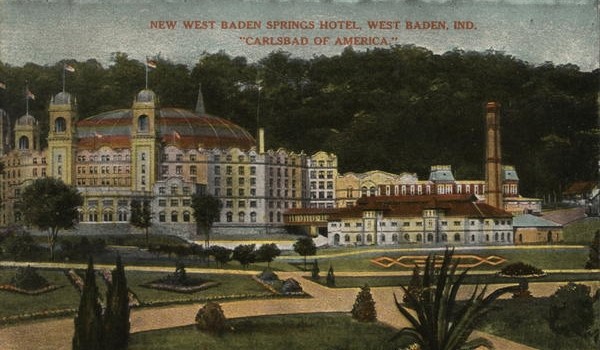

Ironically, although Larry had lived all his life in the West Baden/French Lick communities, he likely knew very little about the goings on in the former West Baden resort hotel that now housed the Northwood Institute. Students staying on campus were housed in converted hotel rooms of the first three stories of the historic hotel structure, the history of which was just short of breathtaking. The six story 388 room building, completed in 1902, possessed an incredible dome that was 208 feet in diameter with a 130 foot high ceiling, said to be the largest unsupported dome in the world. Visitors soon discovered that sights and sounds were distorted in the spectacular open area due to its immense size. The owner dubbed the magnificent structure “The eighth wonder of the world,” believing his place could outdo the nearby resort hotel in French Lick.

For the next three decades, wealthy folks from all over the nation and from Europe flocked to take advantage of the properties of the spring water available at both hotels while enjoying the pastoral hills that surrounded the hotels’ location in the long narrow valley. Many too came to partake in conventions and entertainment, including celebrities and politicians of all sorts. Some guests sneaked off to the illegal gambling joints in the area as well. There was a circus wintering there, sports figures and movie stars staying at most times, and even a few professional baseball teams carrying out spring training on the grounds. But there was also a strange dichotomy in the valley, the local people, mostly folks of more meager means than the guests who came to the resorts, going on about their quiet daily lives.

These good times at the West Baden resort would not last, its fortunes taking a quick nosedive when the stock market crashed in 1929. In 1933 the hotel’s owner, Ed Ballard, sold the building to the Jesuits, who established a seminary there called West Baden College. After an over forty-year run, the Jesuits left in 1965 because of declining enrollment. Good fortune saved the grand building when a Michigan couple bought the now aging structure and donated it to Northwood Institute of Michigan to operate a four-year satellite college campus there in 1967. The school offered degrees in Advertising, Automotive Marketing, Business Management, Fashion Merchandising, Hotel and Restaurant Management, and Retailing and Marketing, among other programs. Many students who attended Northwood found the atmosphere created by the unusual dome and the old hotel grounds exotic and mystifying, hinting at events and ghosts from other eras. The strong sense of place also drew the community of students into a close-knit group. And, of course, Northwood also had a collegiate basketball team that was fun to watch.

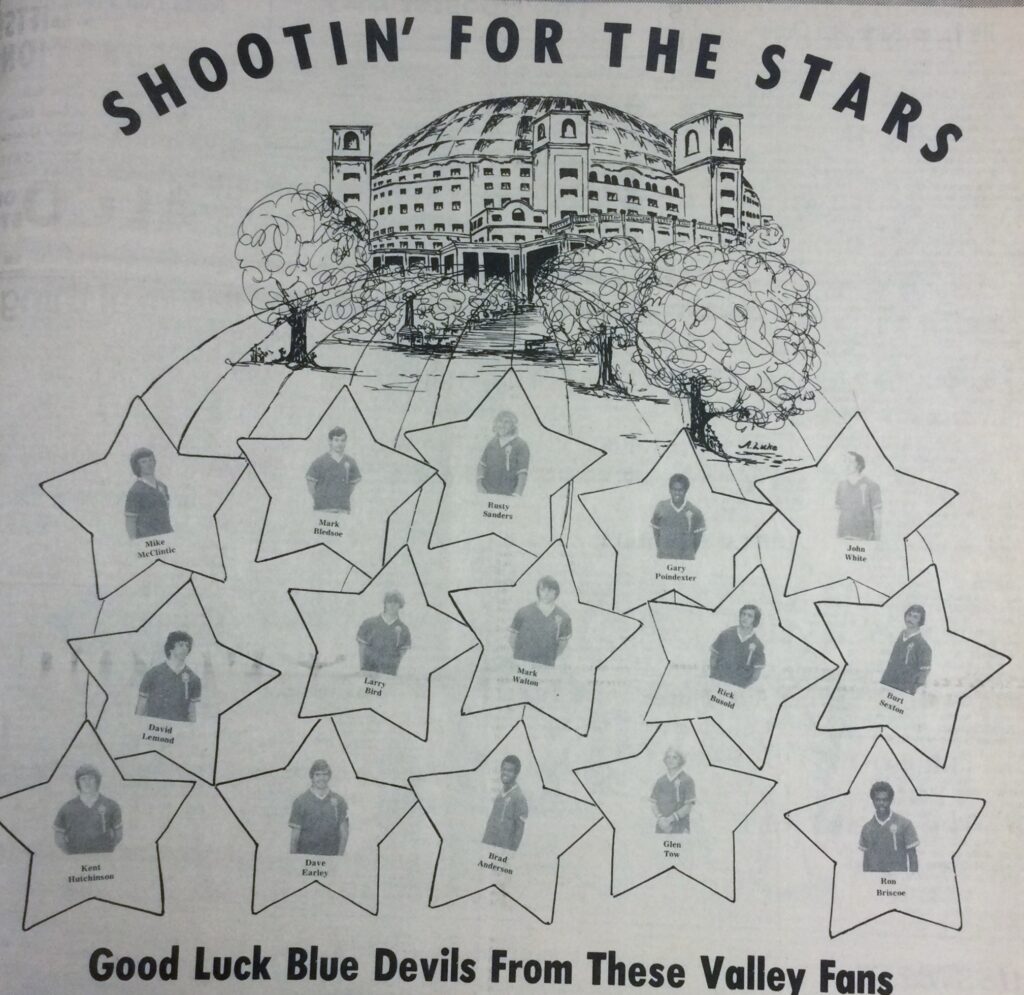

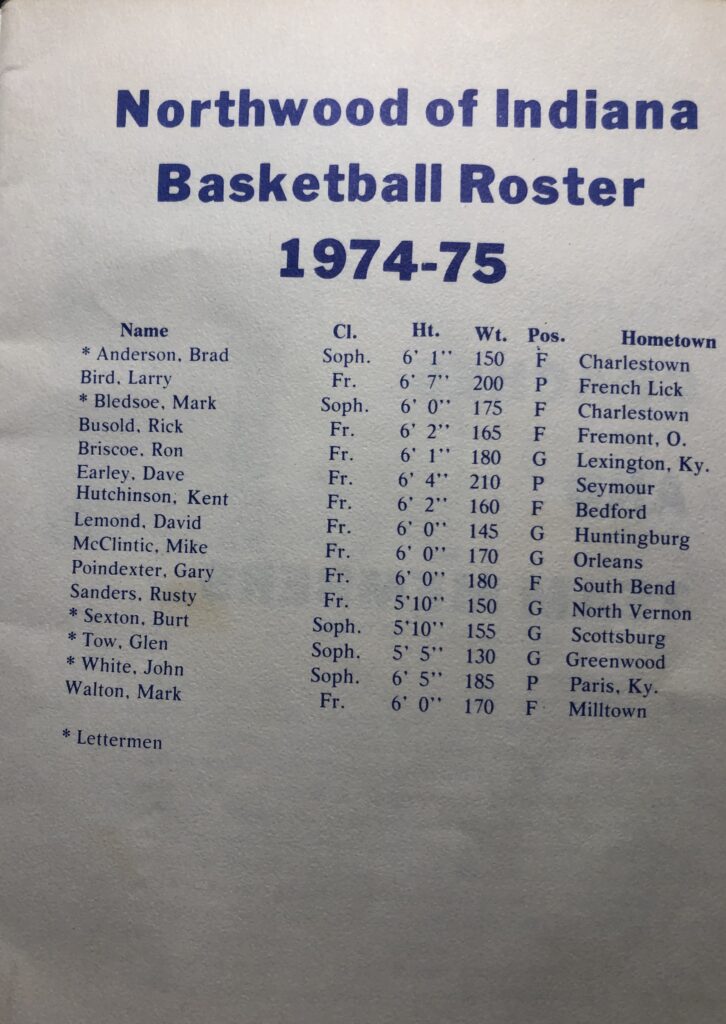

It was likely that second-year head coach Larry Bledsoe was thrown off kilter with Larry’s coming. Michael Rubino, in his 2015 article about this period in Larry’s life, believed Coach Bledsoe “was more concerned with the players in his own program as the season approached,” although the writer went on to say, “he wasn’t about to turn away a player of Bird’s caliber.” Of the returning squad, Bledsoe had 5-5 playmaker “mini-guard” Glen Tow from Greenwood High School up by Indianapolis and several new local recruits like 6-4 Dave Early who came from a solid basketball tradition at powerhouse Seymour High School, plus Mike McClintic from Orleans and Kent Hutchinson from Bedford, both of these players having been on high school teams that had beat the Springs Valley squad that Larry played on the year before. Interestingly, one of Larry’s high school teammates, John Carnes, was also on the roster, but dropped out before practice began.

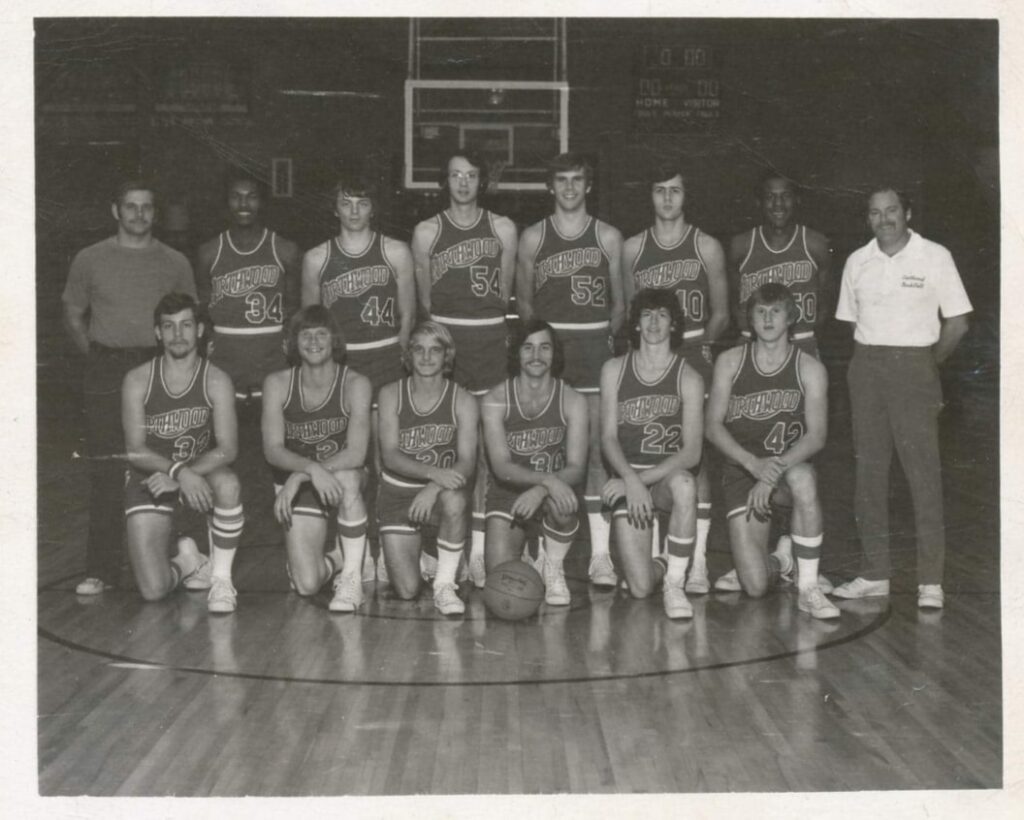

Larry’s coming to Northwood quickly brought attention, the athletic department’s Basketball Press Book hopefully noting that with the addition of Bird, the season might be an exceptional one.

The 1974-75 basketball season will provide a mysterious and exciting voyage for the Blue Devils. Entering the first season as a two year college, the Blue Devils will be faced with an entirely new schedule and many new faces on the basketball team. The biggest strength will be the depth the Blue Devils will possess. There will not be a first five, but rather a starting five with many players seeing action. Although lacking in over-all size, the blue devils will have 6-8 Larry Bird, 6-5 John White, 6-4 David Early on the front line. Speed and quickness will be another asset, but inexperience could hurt the team in the early going.

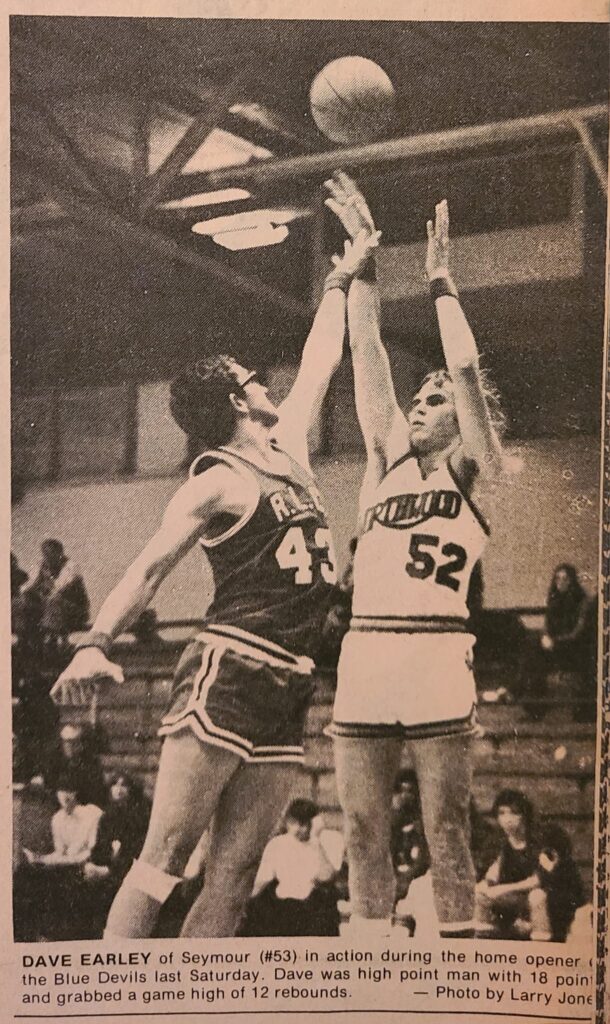

Of all of Coach Bledsoe’s new recruits, before Larry came into the picture, Dave Early ended up being the nicest surprise, one of those basketball players who were late bloomers, making a coach feel as if he had accomplished something after working with them. But this aspect would unfold after Larry Bird left the team. Meanwhile, the Seymour recruit recalled the complete surprise he and his other teammates experienced when Coach Bledsoe announced that the former Indiana high school All-Star player and once IU recruit would be showing up in practice. “I know I was excited, and when we started scrimmaging, Larry lived up to his reputation. He was great, playing at a whole other level.”

Just after Larry joined the team, he and the other players had their pictures taken for the basketball sports program booklet, wearing their Blue Devil warm ups, the distinctive pitchfork design on the jacket’s left side catching one’s eye. Larry looks lost and disconnected in his portrait, staring not at the camera but gazing up to one side instead, hoping, perhaps, to grasp some insight into what seemed an unfathomable future.

While the Blue Devils played their home games at the local Springs Valley High School gym, they usually practiced in the old West Baden High School gymnasium called Sprudel Hall. Dave Early was surprised by how ancient the gym seemed, filled with the atmosphere of faded glory and a few ghosts, despite having only a few rows of bleachers on both sides at the floor and at the upper levels, a stage at one end and a brick wall at the other. “It was a very old, drafty place, with hardly any space between the out-of-bounds and the stage, wall, and bleachers.” Still, the players were excited with Larry being in their midst.

Glen Tow was tasked by Coach Bledsoe to help Bird get his books for his classes and to assist with any other problems that might come up connected with Larry’s school work. They must have been an odd-looking pair, the 5-5 Tow and the 6-8 Bird, walking together inside the Northwood atrium. An event, however, seemed to foreshadow what would soon follow. When Tow explained to Larry that he was ready to go to the bookstore to help get Bird’s books for his classes, Larry just responded, “I won’t be needing any books.” Much later, assistant basketball Coach Jack Johnson assessed that Larry was unsettled the entire time there, having “trouble attending class” and being “very undisciplined.”

Larry did come to every practice, and while his family lacked a vehicle, Bird found ways of getting there, showing up one memorable time in a squad car, having talked a local policeman into giving him a ride from French Lick to Sprudel Hall. After practice, all the players but Larry were eager to get back to the Northwood campus, as the culinary arts people often prepared the meals. “We had great food,” Dave Early explained, “but Larry never went with us. Instead, we’d leave the lights on in the gym, and he would stay in there by himself, drop-kicking the ball or throwing it off the backboard or walls to grab and shoot basket after basket.” A few times, while driving around late at night, Northwood team players noticed the lights were still on in Sprudel Hall and realized Larry was still at it. Of course, this was always Larry’s go to response to pressure—shooting a basketball again and again, finding a rhythm, hearing the swooshing of the nets, shutting out an uncontrollable world.

When ticket sales for Northwood home games were announced in late September in local newspapers, Larry Bird’s presence on the team was often emphasized. This built up anticipation once more among folks in the Valley that they might once again see Bird doing amazing things on the basketball court while leading the Blue Devils to a great season. True, it wouldn’t be at an IU level, but it would still be Larry.

By November 16, the Northwood team had played two tough scrimmage games, one against Bellarmine College from Louisville and another against Indiana Central College located in Indianapolis. Both schools were four-year college division schools and had strong teams. The results indicated that Larry’s heart may not have been in those games. One newspaper sports headline, for example, observed, “Early Impressive for Northwood Blue Devils.” In comments to a sports reporter about the contest, Coach Bledsoe noted that he too was “particularly pleased with the play of David Early,” who hit 11 of 15 from the field in the contest with Bellarmine. Meanwhile, Larry Bird had a cold shooting night, making only 7 of 22 field goal attempts. Bird did better in the next game against Indiana Central, scoring 22 points, but the Blue Devils were beaten by the tough Indiana Central squad, and Coach Bledsoe chose to highlight Mike McClintic’s play in the game, noting Mike’s tough defense and his shooting 6 for 9 from the field.

It was at this point, in mid-November of 1974, on the very cusp of the Blue Devils’ first regular season game that Larry Bird disappeared. As assistant coach Jack Johnson put it, “He just dropped out of sight.” Some thought at the time that Larry became aware of losing a year’s eligibility if he played in even a single regular season game for Northwood. It’s possible that Larry was told this on one of the occasions when the Northwood team practiced before the scattered college scouts who typically watched Larry from the stands. Mike McClintic recognized one of the spectators as an assistant coach at the University of Louisville. “I knew who he was because the same guy had helped Coach Denny Crum recruit my high school teammate, Curt Gilstrap.” McClintic, one of Larry’s old Orleans High School rivals, may have also been the first to know Bird was leaving the Northwood program. “We were practicing in the Springs Valley High School gym for a change, getting ready for our first regular season game, and suddenly Larry comes over to me and puts his hand on my back. ‘I’m out of here,’ he said, and he walked out of the gym.”

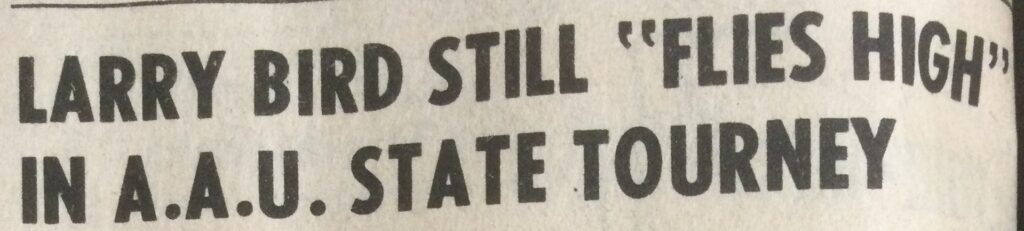

Of course, the rest is history. Larry began working for the city, finally making enough money to buy his first car. And he played basketball too, in independent tournaments like the Evansville Tri-state tourney and for the Hancock Construction AAU team that Larry helped lead to a state AAU championship and also to a win over the 1975 Indiana High School All-Star team. Such instances of Larry’s success once more on the basketball court were quickly noted by the local newspaper, the narrative giving the community a reason to love Larry Bird again.

Larry Bird, 6-7 forward for the Hancock team, helped his team tremendously by playing some of the best basketball anyone in Indiana would ever want to witness, which everyone was sure he was capable of doing in the first place. Anyone who witnessed the “super’ ball playing of Larry Bird in the tournament should realize now that he is one of the smoothest and most capable players in Indiana today.

For Larry Bird fans who longed to witness and be a part of the Bird saga they had previously enjoyed, it was only the first taste of amazing things to come.

The Northwood players went on with their basketball journey as well. After Larry left, Dave Early was called into Coach Bledsoe’s office and told by the coach he was going to take Bird’s place as “the shooter” for the team. Early was, as noted, a late bloomer and felt a lot of pressure in the new role. But he did come around to get the job done, leading the team in both scoring and rebounding, and popping in twenty-five points in a win over 23-3 Malcolm X College of Chicago. Mike McClintic was often a catalyst for victory as well, with his clutch shooting and dogged defense. The Blue Devils finished 15-11 that season. The next year was even better, Dave Early leading the team to a 19-8 season and winning his second MVP team Award. He would be the team’s first All-American and would have the honor of seeing his jersey number retired.

With hindsight, it is clear Larry’s “lost year” was not a “brazen choice,” but rather, as Michael Rubino noted, the path to becoming a legend. Nevertheless, it is intriguing to think what might have been had Larry stayed on with Northwood. Of course, the story of basketball in the state of Indiana is just full of tales of what might have been and of roads not taken.

Sources:

Book and article sources used for this work include Larry Bird’s autobiography, with Mark Ryan, Drive; Lee Daniel Levine’s Bird: The Making of an American Sports Legend; the 1974-1975 Northwood Basketball Press Book; and Michael Rubino’s 2015 article in the Indianapolis Monthly, “Larry Bird’s Greatest Shot was the one he Didn’t Take.” Newspapers used include the Springs Valley Herald, Seymour Tribune, Bedford Times Herald, Evansville Sunday Courier and Press, Indianapolis News, Louisville Courier and Journal, Munster Times, Kokomo Tribune, and Lafayette Journal and Courier. Interviews were taken with Larry Bledsoe, Dave Early, and Mike McClintic.