Lost. A concept with many different connotations, many different vibes. Forlorn. Forsaken. Damned. Haunting notions, easily employed in an entertaining story. Now add the presence of a river.

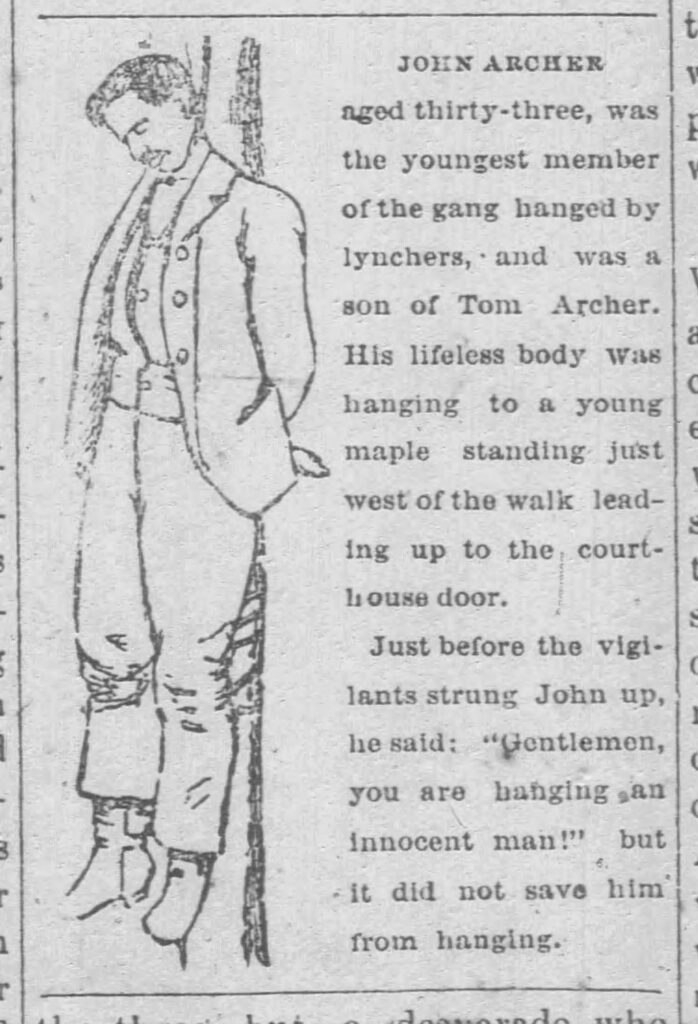

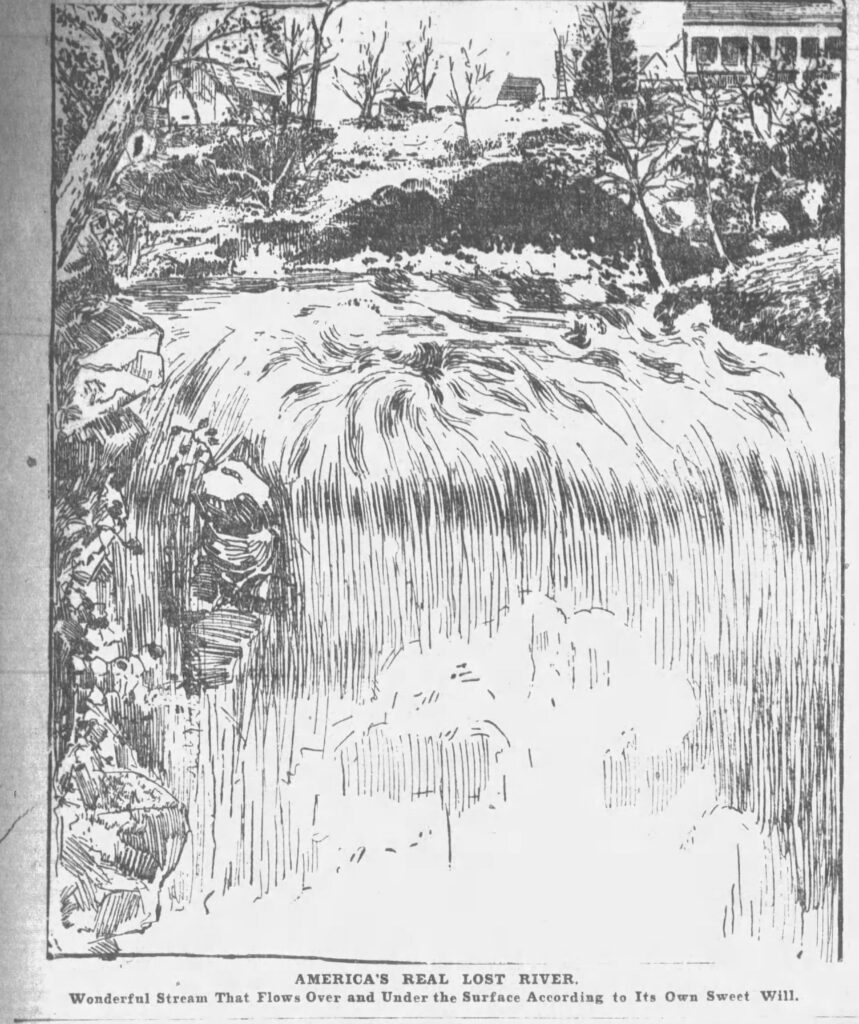

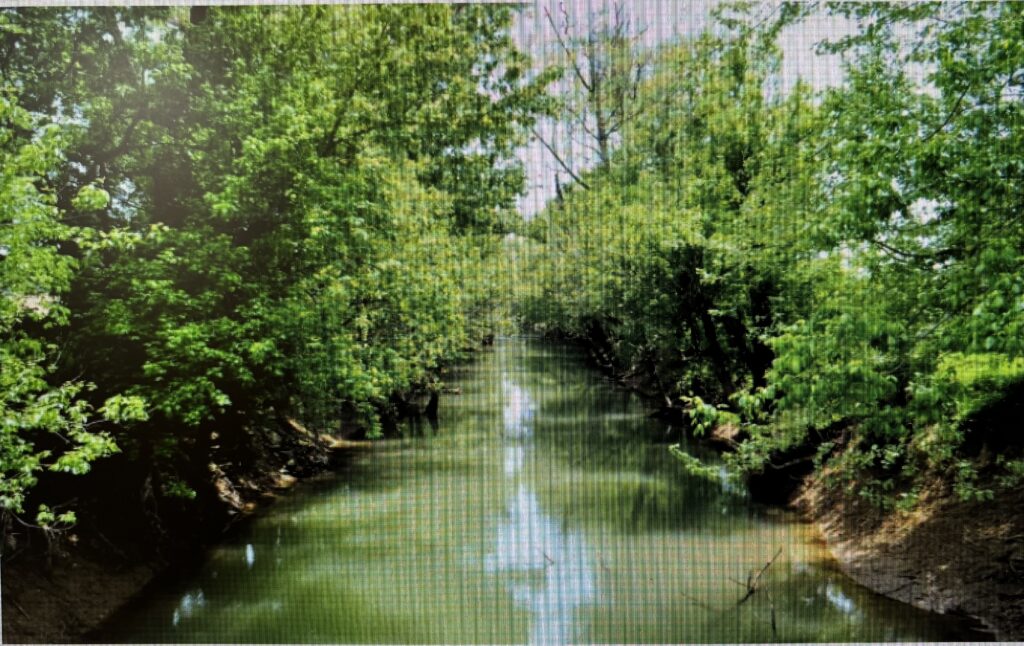

In reality, Lost River is a geologic oddity, a narrow, sluggish stream that runs off and on underground in a region of southern Indiana riddled with caverns. For much of the 19th century, the place was a daunting landscape of deep woods and hollows, of caves, bad roads, or no roads at all. It was a perfect out-of-the-way area for outlaw groups like the Archer and Reeves Gangs, for southern sympathizers who filled the ranks of the Knights of the Golden Circle, and for vigilante whitecaps who tried to counteract the lawlessness of that place and then turned out to be worse than the criminals. One Indianapolis newspaper in the late 1880s described the region as “wild and broken, abounding in hills, valleys, and rocky fastnesses, with numerous caves in the neighborhood to aid the evildoers to hide from the light of day.”

But there were a few lighter reports about the area, one featuring Lost River. Written in 1900 by a member of the United States Geological Survey Department, E. M. Kindle, the piece told the exciting tale of a Lost River underground boat excursion. The story, carried in newspapers across the country, related a rather romantic notion of the exotic environment, explaining, “The wonderful stream flows over and under the surface according to its own sweet will.”

But even the scientific minded geologist could not help but hint of the strangeness of the river and the region, as if it were all haunted by faded events, the kind of odd stories preserved in local folklore, like some curious, pickled form floating in the cloudy liquid of a jar, sitting on the back wall shelf of a country store.

________________________________________

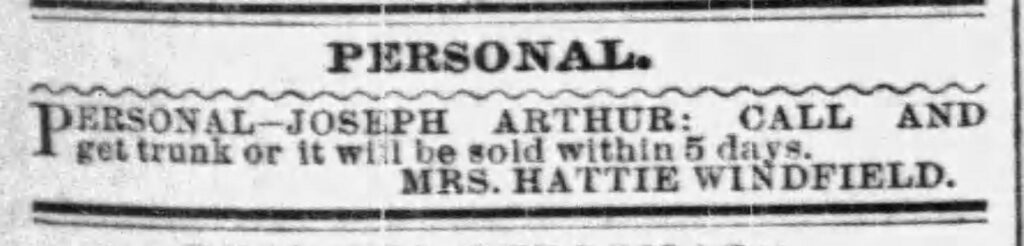

In the same year as the geologic story about Lost River appeared in newspapers across the nation, the successful New York Broadway play, Lost River, hit the boards and then traveled throughout the nation during the next several years. The story centered upon the people in and around the West Baden Resort and the southern Indiana valley in which the resort nestled. The tale was the brainchild of playwright Joseph Arthur, a Hoosier who had left Indiana years before, after changing his name. It would be his last play writing effort; his career path having followed the same kinds of comings and goings as the winding Lost River through the mysterious karst landscape.

Theater plays were the “Hollywood movies” of that time and place. Every major newspaper in the nation, and many smaller ones, carried frequent full page reports about the latest twists and turns concerning this kind of entertainment— stories of the writers, the actors and actresses, and the plays themselves, stirring up excitement about upcoming shows. These adds worked. Large crowds of people packed small playhouses and large ornate theaters to see the famous actors of the day and to escape, through romanticized stories, the boring humdrum of life.

Joseph Arthur certainly caught a strong psychological tailwind in his final work, his play, Lost River. At the time of its performances across America, many citizens were fondly looking back at the recent close of the American frontier and at the sad passing of isolated small-town communities and their pastoral ways. This nostalgic turn was made more pronounced by the quickening pace of the modern world with its new technologies as the century turned to 1900. In order to better capture this fading world, Arthur set many of his plays in southern Indiana, stories such as Blue Jeans and On the Wabash, the latter taking place in Posey County.

The Lost River writer had another entertaining card up his sleeve. He was also known for his special effects, in the case of the West Baden story, a viaduct built on the stage for the last scene, made of glass so the audiences could see the water flowing and surging as the hero saved the girl.

Interestingly, the play’s author explained that his deepest motive for telling this story involved the ongoing tension between the local West Baden community and the sophisticated outsiders who flocked to the resort during its season.

My moving impulse was to portray as realistically as I might the remarkable and picturesque differences between the primitive people who are to be found so near the famous resort of West Baden Springs and the richly dressed, refined, and cosmopolites that are drawn to the place. The contrast of the two widely divergent grades of humanity is a striking one when shown on stage.

Joseph Arthur’s comments suggest that one would do well to start with the setting of West Baden Springs as a way of understanding the many different aspects that converge to bring forth this once well-known and well-received American play. Remember too, it was always about the water, whether it ran mysteriously underground, in an above-ground river channel, through an aqueduct, or bubbled up from the ground, offering natural and miraculous medical remedies.

________________________________________

Persons living in the United States in the 19th century were often in as much life-threatening danger from the medical practices and remedies of that day as they were from the diseases themselves. By the mid-1800s, quack medicines were sold everywhere and heavily advertised in every newspaper. One troubling condition was constipation, the fear of the problem made worse by the medical world coming up with the theory of “intestinal autointoxication,” a supposedly life-threatening situation. Mineral waters found in natural springs often possessed laxative powers that helped combat this disease.

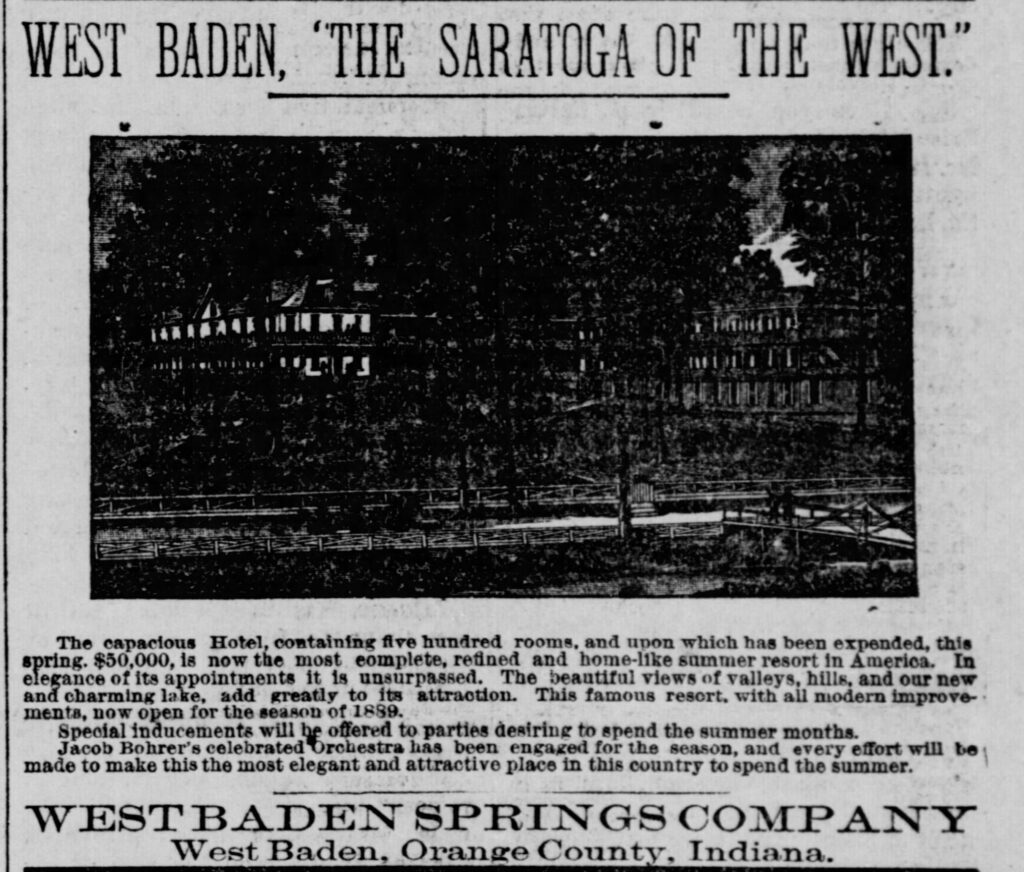

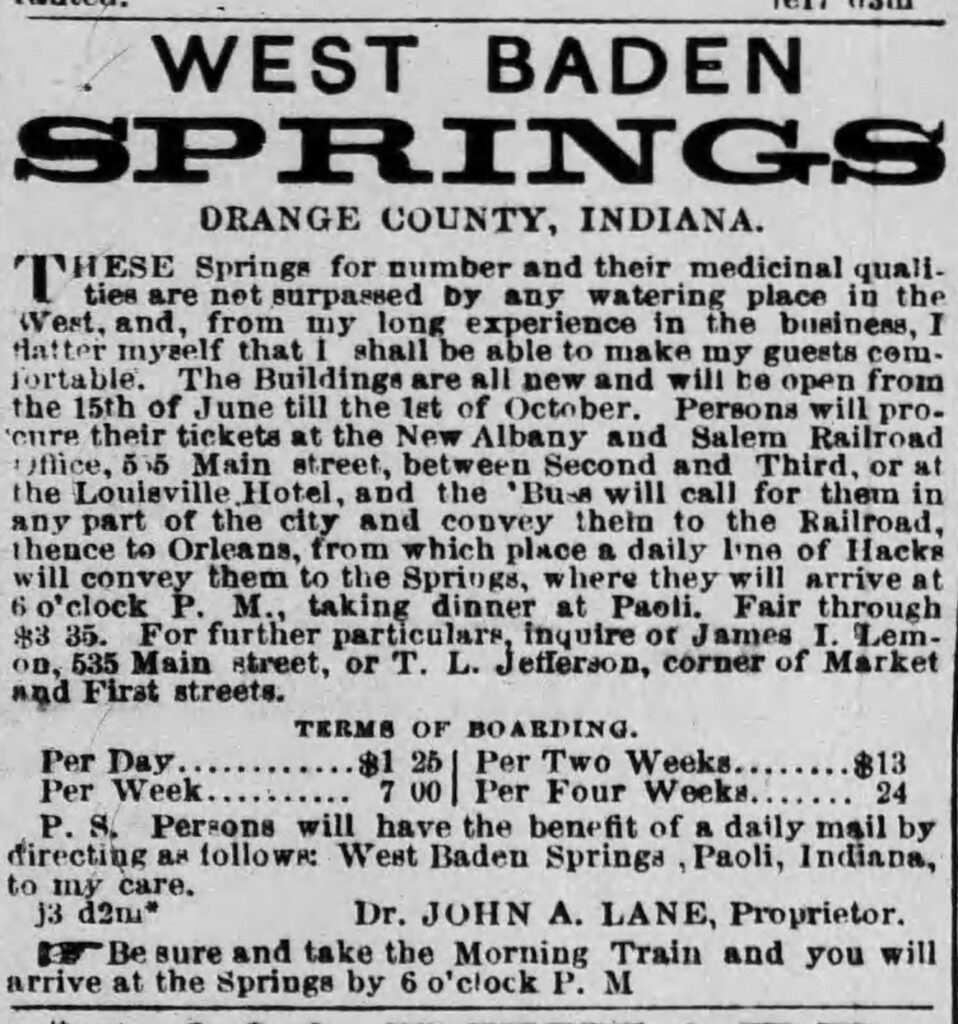

The mineral springs in the French Lick/West Baden area, located in a long narrow valley, had been known to humans since the Native Americans lived and hunted in the area. Thomas Bowles built the first hotel/resort at French Lick in 1845. In 1852, Dr. John Lane constructed another hotel at nearby One Mile Lick and christened it the Mile Lick Inn. In 1855, Mile Lick changed its name to West Baden, a reference to the much older and world-famous Wiesbaden spa town in Germany, a way to announce its interest in the mineral spa business. Lane wisely renamed his hotel, the West Baden Inn. By the early 1860s, the place was known as the West Baden Springs Hotel.

The spring water both hotels provided possessed a high concentration of magnesia, lime, and soda and was said to quickly put the human body back in a state of regularity. Soon, however, more claims were made about the healing available at these springs, the waters supposedly helping to ease those with rheumatism, liver disease, jaundice, gallstones, among other ailments. At one time, the waters were said to be able to cure up to fifty aliments.

But with these claims came more subtle promises, those having to do with pleasure.

In 1860, the place was operated by Dr. John Lane. The Louisville, Kentucky Daily Journal offered this report of Lane’s resort.

A considerable number of the ladies and gentlemen of Louisville are enjoying the cool air and dust-free air these August days at West Baden Springs. This well-known place for health-seekers and joy-seekers, and lovers of romance and beauty in nature, is one of the most desirable in the country. There is hunting and loving, and all kinds of merry making, from flirting to fishing. Dr. Lane, the proprietor of these springs, has left nothing wanting to make them popular in all respects for health and pleasure.

Toward the last decades of the 19th century, high-stakes gambling, although illegal in the state, was loose in the Valley, a local paper noting, “The place is known as the ‘Monte Carlo of Indiana,’ where gamblers ply their vocation.” The resort, claimed the reporter, was “a sort of Hot Springs without the danger of contamination from some loathsome disease.” And that wasn’t all.

Political groups, such as the corrupt Tammany Hall crowd from New York City, came to West Baden to enjoy the healthy practices and pleasures offered there, and to seal secret political pacts. One newspaper called West Baden, “Tammany Hall Resort.”

Then there was the sports crowd. Professional athletes, especially famous boxers of the day like Jim Corbett, came to the resort to train, taking the water cure in the mornings, and working out through the days. Also, several professional baseball teams, including teams from St. Louis, Chicago, and Louisville, carried out spring training there, using the baseball field that sat inside a two-storied oval bicycle racetrack with a roof. Other facilities included an up-to-date gym, bowling alley, and swimming pool.

It was believed the mineral water and alcohol were not compatible, another reason for athletes to get in shape at West Baden. Actors, getting ready to begin a season, also came to West Baden Resort for the same reason. “As a chaser, the waters of West Baden invariably proved fatal,” claimed one newspaper. A New York paper reported how one actor taking the cure, “will, of course, be a pronounced temperance advocate until the Indiana water is completely eradicated from his system. The last time he went to West Baden, he remained without tasting liquor for six months.” A local paper told how even “Wall Street stock exchange brokers” also “took the cure” at West Baden to clean out the results of heavy drinking and thus perform better in their money seeking efforts. “The beauty of the water is this,” crowed the report, “no man can drink it and whiskey at the same time.” As a bonus, these Wall Street fellows could “have a try at any form of gambling.”

But for every celebrity, there were dozens of more regular, howbeit, wealthy folks from Louisville, Indianapolis, Chicago, and from across the nation, sitting on the cool wrap-around porch or walking through the deeply shaded, idyllic landscape, escaping the noise and the heat of the city. The regimen for taking the water was exact, according to one Indiana newspaper. “Arising at 6 or 6:30 a. m., one drinks at intervals for fifteen minutes a glass of hot water from spring No. 7 until he has imbibed from two to four glasses of water. A half hour after the last glass he eats breakfast. Two hours after breakfasts he begins drinking again.” This time the water was taken cold, “At intervals of a half hour. Two or three glasses are taken before dinner.”

Between these drinking bouts, the cure seeker could “take exercise,” walking the quiet, groomed grounds, taking bike rides, or heading to the “pony track.” Eventually, both French Lick and West Baden hotels ended up bottling their waters, the former naming their product Pluto Water and the latter calling theirs Sprudel Water.

These many elements— the prominent stage, sports, and political celebrities, mixing in with the regular clientele, the adventurous and not always legal activities, the curing procedures— made the resort famous. But it would take a New York playwright who lived his early life in Indiana to find another more pastoral and charming aspect to West Baden.

_______________________________________

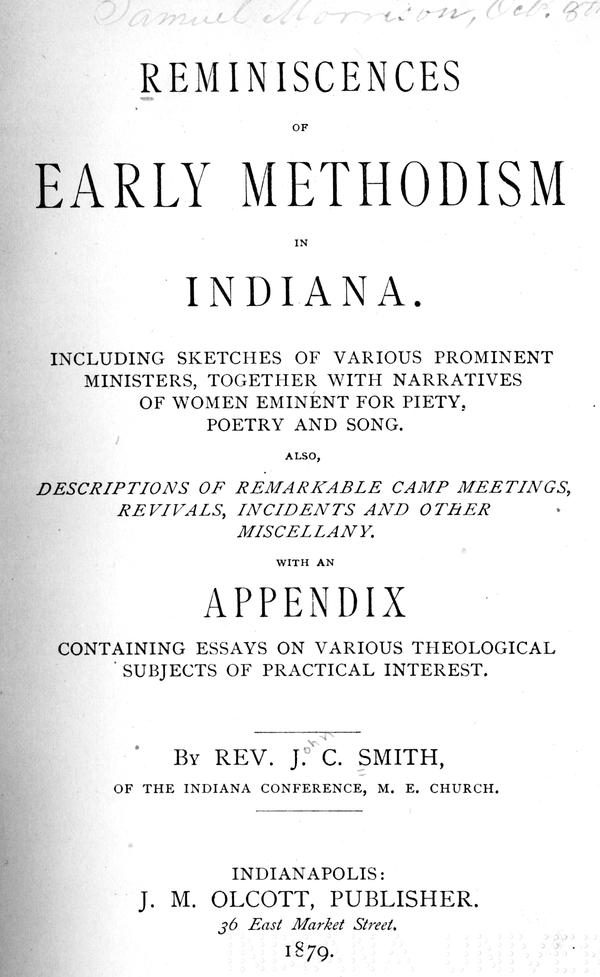

Joseph Arthur was born Arthur Hill Smith in Centerville, Indiana, in 1848. His father, John C. Smith, was a leading Methodist minister in the state and authored Reminiscences of Early Methodism in Indiana, the definitive history at that time regarding Hoosier Methodists. Rev. Smith seemed an unlikely father to have a playwright for a son. On the other hand, it was never easy being a preacher’s son, especially when you’re wired for adventure. This tension is evident in the minister’s short description of his son’s activities at the 1879 release date of the Methodist history, an attempt perhaps to put an upbeat face on his son’s unusual lifestyle. “Arthur is traveling in Europe, where for two years past he has been reveling amidst grand archaeological ruins and living palaces, churches, monuments, and other wonders of the old world.”

In truth, by this time, Rev. Smith’s son had changed his name to Joseph Arthur and had recently failed in his attempt at being a circus performer. “My father entreated me to read good books,” the son later recalled, “but I’m sorry to say that I preferred the yellow back dime novels series to the classics.” The soon to be author of plays got busy traveling all over the world, putting together theatrical shows and writing pieces of interest for American newspapers. In 1880, Joseph Arthur wrote a brief letter from a theater in Bombay, India, to a director of theatrical minstrel troupes asking if the manager could arrange to send an acting group to Bombay. It was not long after this that Arthur went to New York City, where a new destiny awaited him, that of a playwright. So how did the young playwright, a son of a strict Indiana Methodist minister get there?

As a boy, Arthur Smith spend time at West Baden Indiana, where his father ministered to a Methodist church. A detailed 1900 newspaper article appearing in the Indianapolis Journal noted the particulars of Joseph Arthur’s younger days in West Baden, especially how he was drawn to staging performances. “Mr. Arthur was a boy then, full of pranks and with the all-conquering fondness for playing circus and putting on shows.” These events occurred when young Arthur gathered “a group of playmates about him,” took forcible possession of a neighbor’s barn, “and with his comrades, gave a ‘show.’ Young Arthur was always the originator of the plays.”

The Lost River author further explained to the Indianapolis reporter how these events were pivotal in his life, as if some old farmer had wandered into one of the barns where a performance was occurring and with a divining rod, located the center of the young boy’s very soul.

Arthur Smith soon chose the name Joseph Arthur to begin his performing career. After failing as a circus performer, he tried his hand at play writing in 1875, an endeavor that also failed. Then he began traveling all over the world, managing actors and plays, and writing articles of interest that American newspaper often carried. Such writing improved his composing style, an unexpected education that served him well when he finally came to New York City to live in the late 1870s.

In 1887, Arthur finally hit pay dirt with his play, The Silent Alarm, an action story with a great “special effect.” Two horses came galloping onto the stage, pulling a steam fire engine. The play would also be a hit in England and run for twenty more years in America. Later, three different silent films would be produced from the play.

In 1890 came another success, Blue Jeans, the first play showing the unconscious hero tied down to a board and headed toward a buzz saw and a horrible death. A real buzz saw was used on stage. Of course, the hero escaped. One critic who “absolutely loved” Blue Jeans wrote, “It is the first play treating Hoosier life and it contains personages and scenes evidently studied from nature.” For some reason, he did not mention the buzz saw. That same year, a play reviewer argued, “Since the day when Joseph Arthur invented a buzz saw to add to the nervous intensity of ‘Blue Jeans’ mechanical effects have been the rage in melodramas.”

The next year, Edward Eggleston, author of The Hoosier Schoolmaster, sued Arthur for plagiarism, claiming the New York playwright had taken the idea from Eggleston’s novel, Roxy, to create Blue Jeans. The suit failed. Later, Arthur playfully said, “Every dramatist is a plagiarist. So is everybody who uses the letters of the alphabet.”

In 1893, a reporter who followed the New York City play writing scene named Joseph Arthur as one of the few playwrights who had grown wealthy in that trade, emphasizing that Arthur also had to depend on the hard work of managing his plays to make enough money. The playwright had also earned a reputation of being a hard task master on the actors who were in his plays.

Then came dry runs. Several less successful plays followed in six years— The Corn Cracker; The Cherry Pickers; The Salt of the Earth; and On the Wabash. By 1899, Joseph Arthur was exhausted from creating and producing plays. He swore he was done writing and took a break. Like many people entering the second half of life, he visited the places of his childhood, including West Baden. It was while walking around the latter area, talking to childhood friends, that he suddenly felt compelled by “a force that had never before come to him,” to write about his youth and the people of the area there. In doing so, he realized he could study and perhaps better understand how his life in entertainment and show business had come full circle.

______________________________________

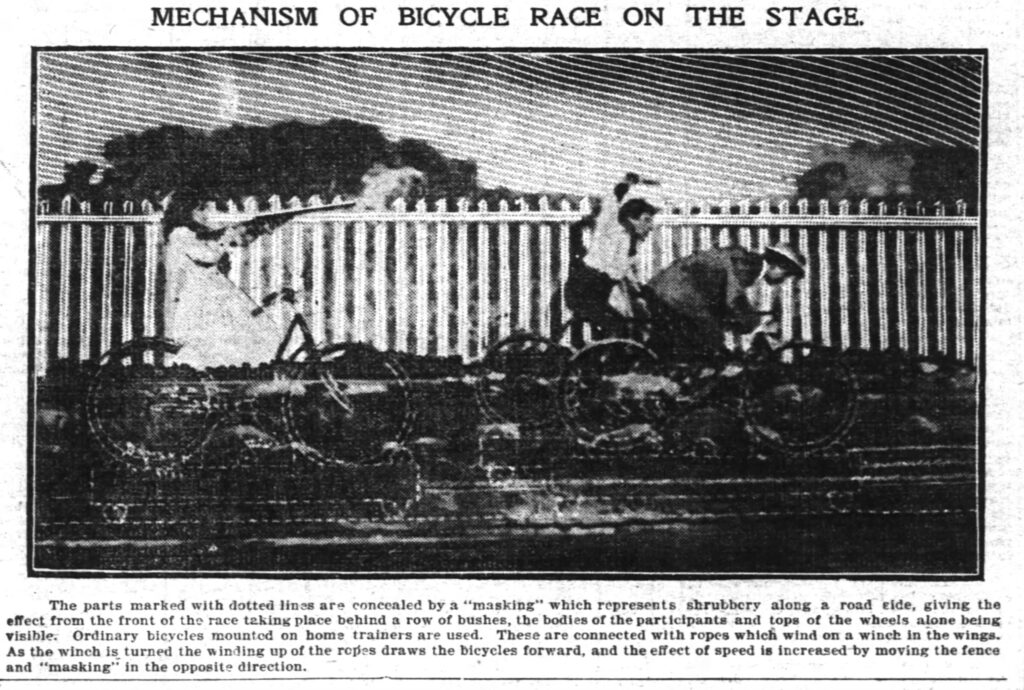

Joseph Arthur was known for producing plays that pleased many types of audiences. He selected the most solid actors and actresses of the day, included plenty of melodramatic, tension filled situations, and added many well-received scenes of gentle humor, often at the expense of characters who played the roles of Indiana country folks. He ended each play on what would be called today, a happy “Hollywood ending.” But his greatest innovation was special effects. So well done was this aspect of his plays that Arthur became known as the originator of “mechanical melodrama.”

Lost River would glow with all these elements.

At the last rehearsal before the show opened at the Fourteenth Street Theater in New York City, everything that could go wrong, did go wrong. One incident was worse than all the others. In an article under “Actors’ Narrow Escape,” the New York Times explained, “The great glass tank used in the fourth act of ‘Lost River,’ the new play by Joseph Arthur which was to have been put on for the first time to-night, burst this afternoon at rehearsal, and the members of the company who were on stage escaped instant death only by the most remarkable good fortune.”

The two main characters “jumped aside as a piece of glass weighting 100 pounds shot past them.” There was “a tremendous explosion” when the big tank holding the water broke apart, “sending one-hundred-pound pieces of glass flying all over the stage and into the auditorium.”

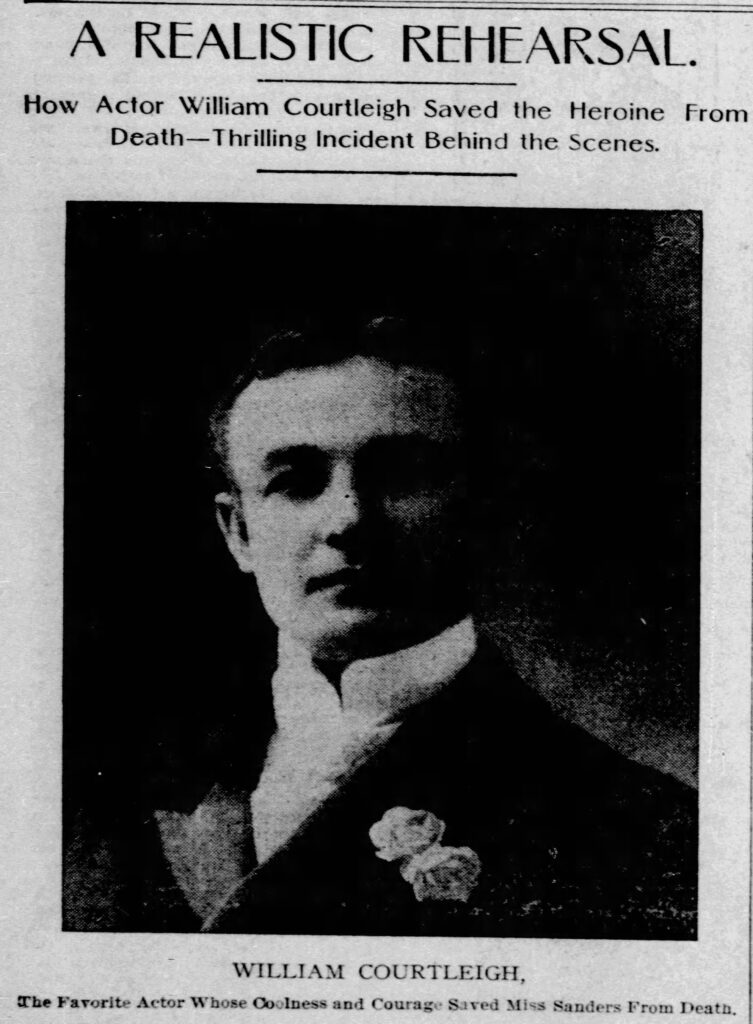

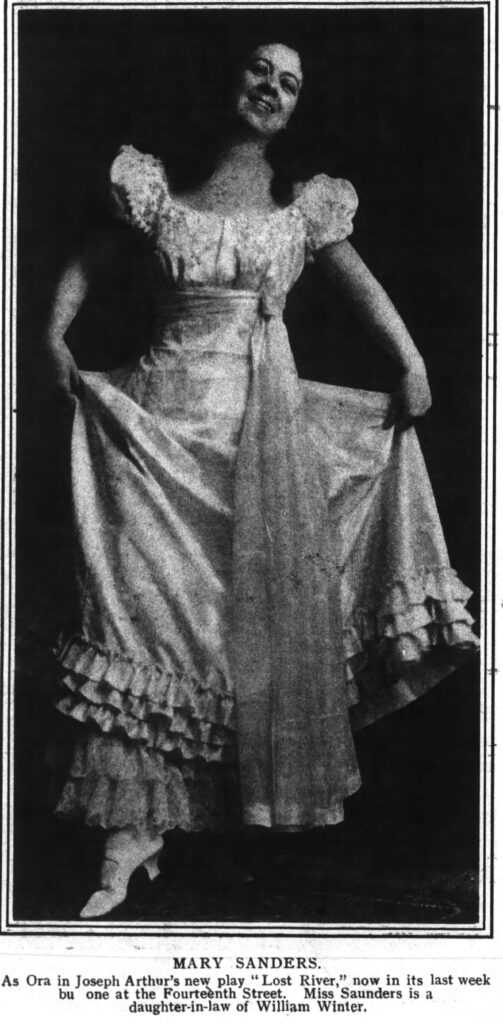

Pretend became reality when the play’s hero, an actor named William Courtleigh, pushed his female counterpart, Mary Sanders aside, “just as a heavy piece of glass landed with a crash where she stood, and thus saving her life.” Another actress broke her arm when she fell while running from the crashing glass. The two tons of water in the tank left ankle deep water on the stage and destroyed several pieces of scenery. Even then, the show was only postponed for a single night.

The final rehearsal debacle seemed to signal the end of foul ups. From its first opening night, Lost River was a hit, running as smoothly as the real Lost River flowed underground. Not only did the special effects wow the crowds, but the actors and the story’s sentimental angles, brightened by many humorous scenes making fun of the rural folks’ unsophisticated ways brought constant laughter, “awws,” and spontaneous applause throughout the show. Three years later, the Evansville, Indiana, Journal News noted, “Joseph Arthur’s masterpiece, Lost River, has won favorable comment and big financial returns in the principal cities of the country.”

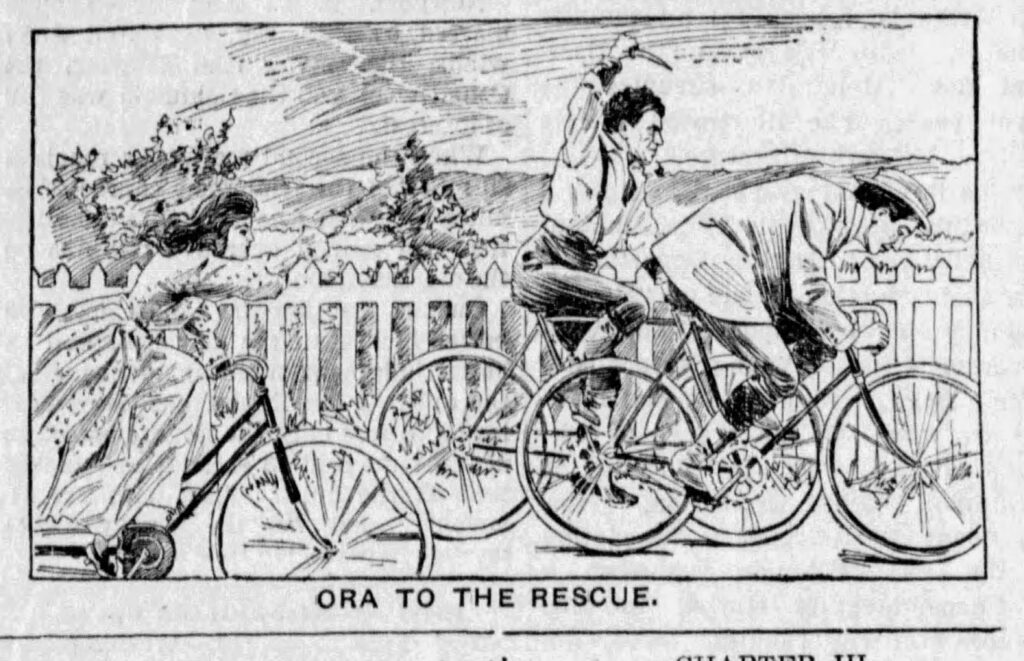

The initial Broadway performance of Lost River featured Mary Sanders, “one of America’s prettiest and most talented of the very young American leading women,” as the heroine, Ora Gates. Ora played a shy, tiny, uneducated local girl who is pure at heart but still able to ride a horse or shoot a gun with ease. One critic argued that “The scenes that pleased most and lingered longest in memory are those which develop the character of the auburn-haired little Hoosier girl, whose grammar is as neglected as her dress.”

The hero, Bob Blessing, was played by William Courtleigh. The actor was known as “a leading man of recognized ability,” his fame now more enhanced than ever by having saved his leading lady during the last rehearsal. Perhaps this led another critic to describe Courtleigh’s portrayal of Blessing as “manly and virile.”

In act one, the audience is introduced to Robert Blessing. He is a contractor from New York City, supervising the building of an aqueduct over Lost River near the West Baden Resort. Interestingly, Joseph Arthur takes poet license here, speaking, for example, of the building of an aqueduct, although Arthur claimed that such a structure was talked about frequently among the locals when he was a boy living there. He also had Lost River rushing by the resort and then disappearing a few miles into the cavern-riddled landscape at the foot of a small mountain. In fact, the river, not much more than a big creek in places, ran just outside the town, and even the tallest hill failed to come close to the height of a mountain.

Conversely, the striking difference between the rich clientele from out East and the local country folk around West Baden was real and was captured first in the ball room scene at the resort when a silly “country orchestry” comes lumbering down a winding stair to play for the guests. Their actions, noted one reviewer at one of the play’s engagements, “set the audience in a roar.”

We also meet the sweet little heroine, Ora Gates, living with her grandmother far out in the country. Other Lost River scenes that captivated audiences included the “realistic” arrival of Ora in a country farm wagon to a country dance where another “country orchestry” played local songs and the actors took part in dancing. The end of act two featured a horse galloping on stage and the hero holding off a mob with just a fire axe. In act three, twenty sheep came on to the stage as the “shepherd” actors stood and sang “pleasantly to the audience.” Then another rescue, this featuring the heroine as she galloped across the stage on a horse, chased by robbers. The hero opened a gate for her to escape her pursuers then backed down the bad guys.

The grand finale— the aqueduct rescue scene, the victory of good over evil, the embrace of Bob Blessing and sweet little Ora Gates— would leave audiences breathless. In many cities where the play ran, the cast was all-but-overwhelmed with curtain calls.

Joseph Arthur was unsure how his play would be received, telling a Boston Globe theater reviewer just before opening night that he “had written his last play. My nerves would not stand another failure.” Reviews of the play, however, were more than solid. They heralded a success. After catching the opening night, the Globe theater review writer declared, “This romance of southern Indiana has much to recommend it to all classes of playgoers. It has a strong love interest, is replete with sensational episodes and thrilling situations, and an abundance of comedy.” Another play critic noted, “The humorous sayings, picturesque clothing, mannerisms and customs of the Hoosiers inhabiting the famous Indiana Valley through which the mysteriously disappearing Lost River flows are a constant source of wonder and amusement to eastern folk.” Then the critic drills deeper, touching on that part of America’s past, as represented by the natives of the West Baden area that were rapidly disappearing, and so fondly remembered. “The exquisite pathos of these rough folk when deeply touched and their bravery in times of peril afford some thrilling situations as presented by the author.” Such accolades continued for the next three years, as Lost River made its way through cities large and small across the nation.

________________________________________

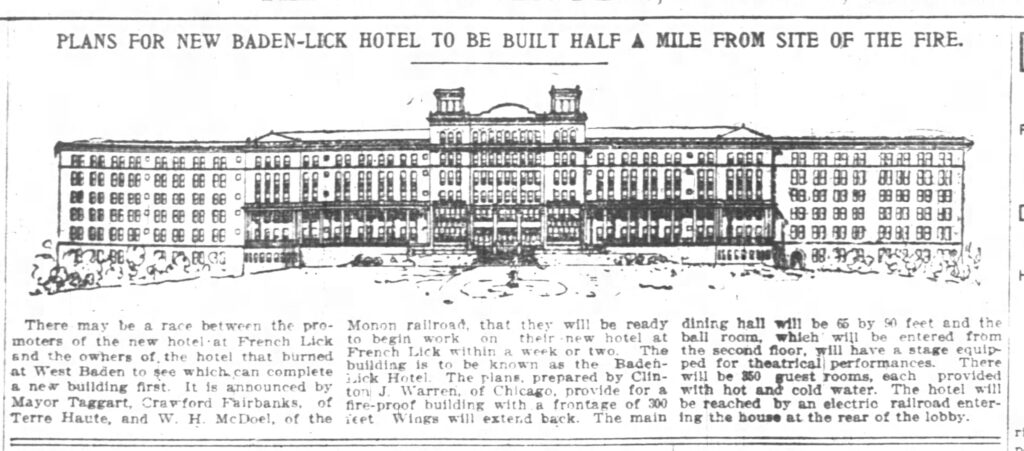

In the early summer of 1901, just one year after the New York City Broadway production of Lost River started its run, West Baden’s 700 room resort burned to the ground in a spectacular fire, the glow of which was claimed to have been seen as far away as Louisville, Kentucky. A local, coming into town the next day, sadly observed, “The sight presented was one not to be forgotten. All that remained of the once famous hotel were two tall chimneys that looked like the towering battlements of a war-beaten castle.”The resort’s main owner, L. W. Sinclair, soon received more bad news the next day when it was announced that the rival resort, a mile away at French Lick, would be building a grand new hotel with 350 guest rooms.

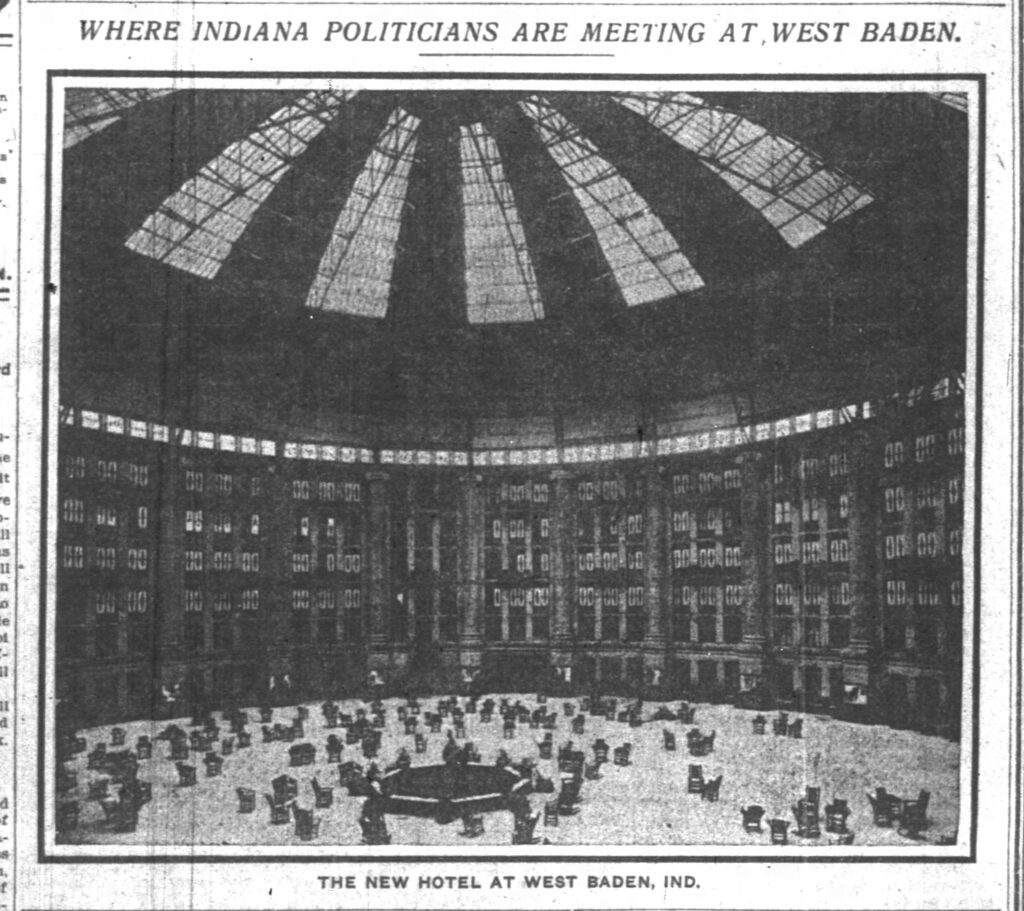

Sinclair, however, did not take the time to blink, putting enough money together to quickly rebuild the West Baden Resort, a one-of-a-kind structure with a great dome and six hundred rooms. The building opened in 1903 and was declared the “eighth wonder of the world.”

The resort and building would go through years of prominence but failed during the stock market crash. For many years thereafter, the building would house a group of Jesuit priests, before being purchased by Northwood Institute and turned into a college. When Northwood pulled out, the building went through a period of decay before it was restored to its previously majestic presence by the Koch Foundation.

As for Arthur Smith, aka Joseph Arthur, he lived long enough to see the ongoing successes of his last work, Lost River. Six years after the play opened, Arthur died after a short bout of kidney disease. He was fifty-six years of age. One can only hope he came to understand that his many productions, especially his last play, Lost River, confirmed his life in entertainment, his stories enhancing the world in some small but effective way, making it a bit brighter place to live.

And whatever ghosts from the time Joseph Arthur wrote of that may still linger, perhaps these spirits find some solace in the quiet beauty of the present West Baden atrium, where the rich and famous and the local West Baden folks still mix and mingle. Ghosts as elusive and intriguing as Lost River itself.