Slipping through the door of Leonard Wilson’s General Store in the 1950s was to step into a place of community and good purpose. Women, their eyes mostly cast down on the small pieces of paper they held in their hands, roamed the aisles, carefully picking out a particular can or box, looking over their glasses as they checked labels, their sensible shoes producing a deep singular tone with each step on the scarred wooden floor. The men, who most often came to get sacks of feed or take a short break from field work, were in less a hurry, sitting in the folding chairs that lined the front north side corner of the store, legs crossed, and chairs reared back against the wall, slowing draining bottles of Coke or Pepsi. Children, gathering in front of candy displays or the ice cream confectionery freezer, held tight to their nickels and dimes, checking out the candy and ice cream selections.

For my siblings and I, a trip to Wilson’s Store was a tonic, a brief escape from the often-dull routine of our remote rural world. The once-a-week trip promised a soda pop, a small bag of peanuts, and a banana popsicle, the latter, on the ride home, melting instantly away as the hot summer wind blasted through the rolled down car windows, leaving one’s hand a sticky but lickable mess.

Oddly, the vitality of Leonard Wilson’s store only enhanced the haunted condition of another nearby store business, a long-closed rival sitting just a few miles from the Wilson establishment. Deteriorated beyond repair, the building had a gaping hole in one back corner of its rotting roof, a not quite round opening that looked all the world like a silent scream. It always seemed too that a small lazy cloud came along, causing the sun to cast a brief shadow whenever my brother, Marshall, and I rode passed the sad place on our bicycles. Perhaps the building smacked too much of failure, of crushed dreams, but whatever the reasons, our pedaling always quickened as we approached, turning us breathless and mute. As we passed in silence, we tried not to stare, to not let our eyes delve too deeply through the open door and broken out windows into the dark heart of the structure, relieved when we were down the road a ways and could begin chatting again, squinting in the bright return of sunlight.

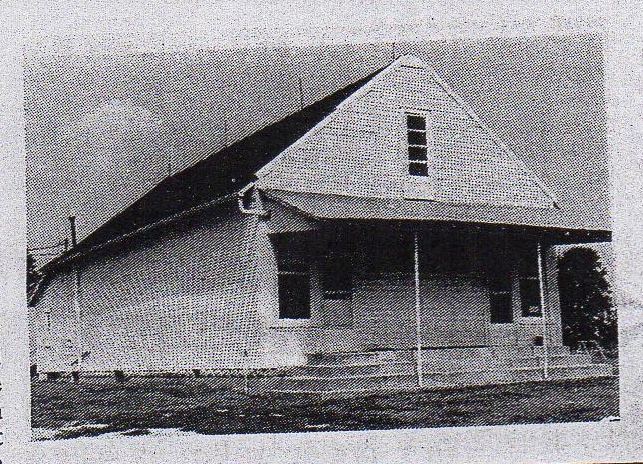

There was yet another former store building nearby, in much better shape and probably much less haunted, a plain looking tan colored structure with a tar roof just starting to sag, sitting almost on the very banks of Horse Creek. It had been operated successfully for a time by Jerry and Bill Wilson, until they either got tired of all the work that went into merchandising or found the location becoming less profitable.

It was here that our Dad, seemingly out of nowhere, decided one day in the late winter of 1959 that he would go into the grocery store business.

In retrospect, it was clear the unexpected endeavor was a direct result of our father’s failure to make the Illinois state police academy the year before. Dad blamed his former car salesman boss, believing he had given the state police merit board a bad recommendation so that Dad would remain a car salesman. Dad’s old boss must have been shocked when Dad did not return to selling cars and down-right amazed when he heard he was going into the store business.

He wasn’t the only one who was surprised.

From the rest of the family’s perspective, despite our love of the country store experience at Leonard Wilson’s, starting our own store business was not a happy jolt. Mom gave no outright expression of being displeased with the new situation, but we all knew she would be called upon to continue doing all the housework and childcare duties, while clerking and cleaning up at the store.

We kids soon discovered we would have a hard go of it too.

Marshall was eight, I was seven, and our little sister, Karen, had just turned four. Our former routine, while often boring, seemed heavenly compared to the new situation of our family’s store operation. Starting in February, we were drug down to the cold store building every evening after school and every weekend, forced to entertain ourselves without TV or our pleasant woods in which to play. Saturday morning cartoons and idle trips to the pantry and refrigerator to get a quick snack were finished. But like our mother, we voiced no opposition, going along with the new scheme, somehow aware without anything being said that the undertaking was of utmost importance to Dad so soon after his state police academy washout.

It was especially cold that February, and our parents spent most of their time at our store—swiping away the thick cobwebs before cleaning and painting the walls, mopping the floors, and washing off and then shining up what seemed like a hundred shelves. It was backbreaking work; thick grime cleaved to every surface, and despite all the cleaning, a touch of dust remained the primary scent.

Marshall, Karen, and I stayed mostly in a back room, using an old roll-away bed as a couch. The only other piece of furniture was a rickety card table with a single folding chair.

A kerosene heater glowed like a weak little sun in the middle of the all-but-bare room, giving off fumes that made our eyes water. For once, we three siblings hardly fought, playing a board game with pieces missing and listening to an old radio that sat in the corner, and I, rereading my tattered Sgt. Rock and Archie comic books for what seemed like a hundredth time.

Despite the heater, the slick concrete floor in the back room stayed as cold as a block of ice.

Two things eventually kept me pacified during those bleak winter days. One Saturday, when Dad was gone to get a used floor freezer in which to keep the ice cream products, a nervous young man, tall and thin, with a head of bushy red hair, walked into the store holding a tattered piece of paper. The odd-looking fellow was a novice World Book Encyclopedia salesman, wanting directions to a few households in the neighborhood that he hoped to hawk encyclopedias to.

“This is the most confusing place I’ve ever been,” he lamented to our mother. “Half the roads turn to dirt trails that run into fields.”

He ended up leaving with good directions to a half-dozen of our neighbors’ houses and his very first sale, one on which our mom got a nice discount.

We thought we’d have to wait to get the set, but so appreciative was the young salesman for the directions that he went outside and opened the trunk of his car, returning in two trips with the one set he typically carried. The purchase was taken to the back room where we stayed, and after he left we gathered around the volumes like vultures, Mom shouting to us to wash our dirty hands before we even thought about grabbing one of the gleaming books.

Normally, Dad would have blown his stack about Mom spending the money, the debt to be paid off on a monthly installment plan. However, his timing may have been thrown off by the presence of the two men who came along to help unload the heavy freezer he’d found, and his hesitation for a few fleeting seconds may have allowed our mom to build up her courage.

“They’ll open the world to the kids, Keith, and they’ll make better grades,” Mom said, repeating the words of the redheaded salesman like a parrot.

She held up the very first volume she had toted out from the back room, a fat “A” standing out on its spine like a letter jacket. The two helpers stared at the book as if it contained holy scripture, and, amazingly, our dad gave up with hardly any fight, save for a small grunt and a command that Marshall and I hold the doors open while he and the two other men wrestled in the freezer.

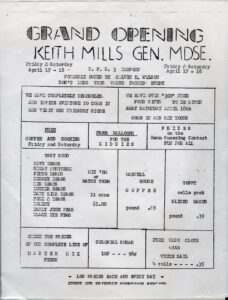

Another announcement of the store’s opening, this one in the Farrington Items section of the Register News

Our Mom, who couldn’t carry a scrap of a tune if her life depended on it, walked away humming an unrecognizable ditty.

The more expensive version of the World Book Encyclopedia was bound in red, but Mom had saved a bit of money by purchasing the cheaper white bound version. Marshall never opened a single page of the books, and Karen was too young to be interested in them. Soon, however, the white covers of our set grew a bit dingy with my handling. I thumbed through them daily and for long periods of time, so engrossed in the colorful picture plates of birds, minerals, maps, presidents, and flags that I would be unaware of the time’s passing.

Another wonderful happening at the same time involved the recently purchased floor freezer that was soon filled with assorted and colorful popsicles, thick chocolate fudge bars, and sherbet flavored push-ups, along with gallon, half-gallon, quart, and pint cartons of every kind of ice cream flavor imaginable.

Perhaps it was out of guilt, our mother letting us choose a half-gallon carton of ice cream from the freezer to eat out of any time we wanted, a circumstance that, like the new encyclopedia set, did not seem to be a big deal to my siblings. I, on the other hand, ate ice cream almost daily, choosing a box of lemon ice cream each time, one containing bits of lemon drops embedded in the mix like tart little diamonds of flavor. I’d slowly enjoy each spoonful as I leafed through volume after volume of encyclopedias, the ice cream half melted and dripping off the spoon towards the end of each wonderful session. When I had finished reading, I’d close the volume then put the spoon I was using in the carton and place the box in the freezer, toward the back, where it would be ready and waiting for my next reading session, away from the other boxes that were for sale.

Slowly, in a trickle, and then, in a deluge, things changed for the better, transforming into what would become a brief and golden time in my siblings’ and my memories. The store opened in April of 1959 complete with a flyer. In part, it announced:

“Keith L. Mills, General Merchandise. GRAND OPENING”

“Free coffee and cookies Friday and Saturday”

“Free Balloons for the kiddies”

“PRIZES on the Jellybean Guessing Contest”

“FUN FOR ALL!”

Everything went well with the opening, except for the jellybean guessing contest, which was messed up by Marshall, Karen, and I getting into the jar too many times before the store opened. It was exciting, our family changing from living in semi-isolation to seeing a daily parade of interesting people, both new and old. Sometimes shoppers brought their kids, and Marshall and I played tag or other quick games with them outside for the twenty minutes or so it took their parents to shop.

In didn’t take long for Marshall, Karen, and I to turn completely decadent, robbing from the candy counter and ice cream freezer at will, our parents either looking the other way out of guilt about our previous circumstances or just being too damn busy to expend energy to stop us. If it was guilt, we played it for all it was worth and had all the candy and ice cream we could have ever wanted.

Once the warmer spring weather arrived, and on into the golden days of early summer, Marshall and I discovered an entirely new and exotic world just outside the store building. The woods and fields next to our house seemed sterile compared to the creek and the land it ran through that nestled next to our store. At first Marshall and I only ventured as far as the ancient iron bridge that spanned the creek, the rough wood flooring with a hole or two, revealing the dark dangerous water flowing below. We would hold tightly to the rusted crisscrossed railings, carefully tossing maple tree whirligigs from the sides of the rusted structure, watching the winged seedlings fall and flutter in their crazy zigzag descents into the brown water. This safe but soon boring routine changed when two of the Boyd brothers, who lived a short distance from our store, down a dirt lane, introduced us more intimately to the waterway.

A full page flyer my parents created about the store’s Grand Opening in April of 1959

Horse Creek was a winding ancient stream created when the last Illinois glacier melted, the released water leaving a deeply etched drainage system with a surrounding landscape of steep wooded hills and ravines. Giant sycamore trees, probably as old as the last small band of Native Americans who hunted thirsty game at the edge of the creek, shaded both banks and the muddy water between, adding a bit of mysterious gloom to the atmosphere. On our first day of exploration with the Boyd brothers, Marshall pointed at a massive tree leaning precariously inward, bowing over the stream, a graceful arch of green. Beached logs and large branches thicker that a grownup’s body but stripped of leaves clogged the waterway in many places.

On that first day of exploring, we came to an eddy of light brown sand, next to deep wide pool of still water. In the pool, a large fish appeared from the depths, its form growing from shadow to scaly flesh as it slowly rose, nipping at the brown surface of the water, taking insects, before disappearing again. On the other side of the creek, a string of sluggish turtles sunned on a long thick root that stuck out of bank and into the water.

It was in this quiet and hidden place that the Boyds, Arthur and Rip, showed my brother and me how to build a small fire to keep the armies of mosquitoes at bay. Arthur, the oldest, lit up a big fat cigar he had stolen from their father to further enhance the protection against the swarms of mosquitoes that owned this sultry place. Marshall took a puff or two before giving it back, the look on his face saving me the trouble of taking a puff.

The time we spent with the two brothers always ended up the same, they leisurely pissing into the creek and puffing on their cigars like frontier rowdies, then catching turtles or setting about picking up fist sized rocks they found on the creek bank and throwing them into the middle of the peaceful pool, laughing their heads off with each KA-PLUNK.

Before long, Marshall and I were going down to the creek without the aid of the Boyd brothers and their stolen cigars. The creek and nearby surroundings teemed with bird and plant life. Giant redheaded woodpeckers, fat cardinals, and brown thrushes darted in and out of the thick entangled vegetation. Waves of honeysuckle and trumpeter vines, the latter with vivid red flowers, all but covered shrubs and trees like green coverlets, or, more figuratively, like a conquering army of Vandals, a group of barbaric Germanic people who sacked Rome, according to the “V” volume of the World Book Encyclopedia.

The environment of the creek was so intense with color, noise, smells, and sultry heat that Marshall and I hardly ever talked when there, the water and its surroundings a huge sacred cathedral. Of course, like all good things, our store business, and its exotic surrounding, did not last.

By early summer, Dad began to look like our dogs when they had been stuck in their pen for too long, the singular expression on his face being a prime example of what a doctor might have called clinical depression. More short-tempered and restless than ever, he now took his time driving to and staying in Mt. Vernon while getting weekly supplies from a wholesale store. One day, we heard him tell Mom that G. B. Holman wanted to hire him back to sell cars, this time as the sales manager.

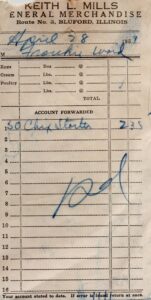

A sales receipt, one of the few artifacts remaining from my parents’ brief adventure in the country store business

“Let’s give it a little longer,” Mom gently suggested.

We kids were struggling too. As more customers showed up, we had less attention from our parents. Left to shift for ourselves, Marshall and I turned sullen and a bit mean, picking on Karen till she screamed or cried, being extra rough with the kids we played with outside of the store building—all-in-all, a less threatening version of Lord of the Flies.

About this time the store roof sprung several leaks at the back of the building, the area looking like an obstacle course of randomly scattered buckets and pails whenever it rained, the drips a jazz-like discourse of dissonant notes whenever the drips began hitting and filling up the containers. Toward the end, even Mom slipped in her work, complaining of aching feet, sometimes not paying much attention to a sale. She still might have hung in there longer about keeping the store open if a lady customer, a distant cousin of my Dad’s family, had not come tearing into the store one afternoon about an hour after her earlier shopping.

The lady pushed her way to the front of the line and slammed a dripping half gallon carton of ice cream on the countertop. She opened the box, her body leaning back from the container as if it contained something vile.

“Look at this. Just look at this,” she repeated.

Almost in unison, everyone obeyed, drawing close and peeking inside.

The carton was a third of the way empty, with a partially bent spoon stuck into the lemon ice cream like a knife.

“My poor husband nearly threw up when he saw that nasty looking spoon,” she said.

Everyone but Mom gasped; Mom shouted out my name.

I suppose I should have felt more guilty, but my mother knew where I kept my special carton of ice cream, way in back of the freezer. It was she who had mistakenly sold it.

After the angry lady and the other customers left the store, our poor mother hung the “closed” sign at the front door and hurried to the back room, us kids right behind her. She sat down on the edge of the roll-away, her body slouched in total defeat, and began to sob. But then, when we drew close to comfort her, she wrapped her arms around us and went into almost hysterical laughter, laughter so infectious, we all joined in, Marshall, rolling on the floor back and forth like a dog and holding his belly, when he wasn’t pointing at me. When he did speak, all he could get out was, “That nasty spoon!”

I think we all knew then that the store ordeal was finally over.