In the first week of September, in 1937, my father became an unexpected statistic, the state health department noting that Jefferson County had one new case of polio that week.[1] What happened the day the symptoms came to my father and after became legend in our family.

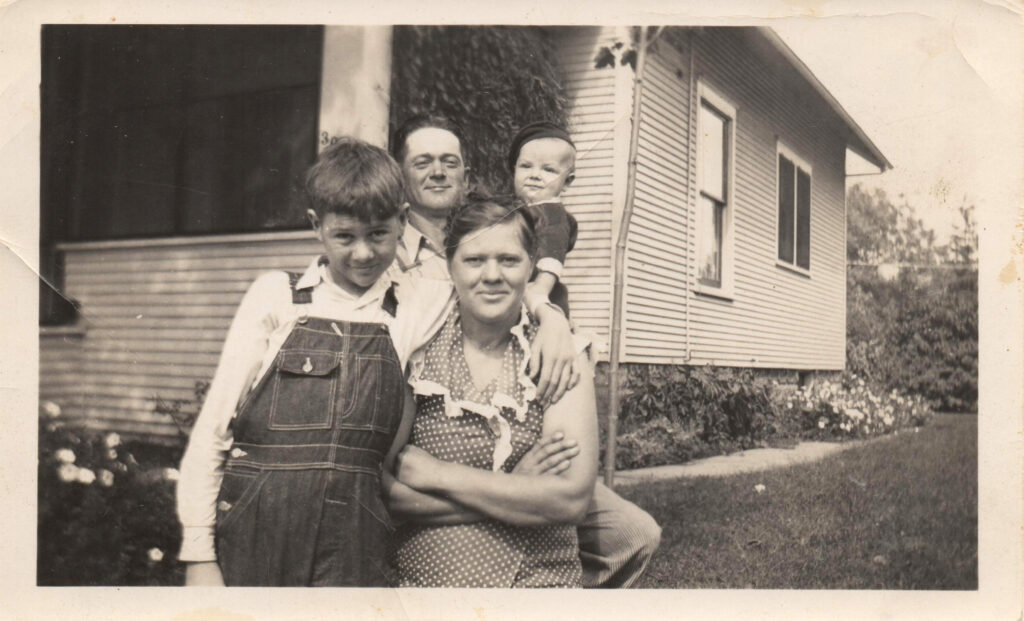

Being a twelve-year-old boy in the Horse Creek region of southern Illinois in 1937 held many pleasures for my father, Keith Mills. Born in November of 1924, he grew up in a rural place Huck Finn would have happily lived—woods, ponds, fields, and the deep muddy swimming hole down at the creek all beckoning my father and his friends in boyhood. Besides the pastoral beauty of the place, my father was born into a large extended family with grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins in all directions. Many of the citizens were as colorful in character as the initial backwoods settlers, telling interesting stories and making over my rascally dad.

For all the enchantment of my young father’s environment, something horrific was ever-lurking. When it came, it came mostly for the children, and it would be this monstrous thing that held my father’s life in the balance for several weeks of his young life.

The year 1937 in southern Illinois featured another record-breaking run of hot weather. The ungodly summer temperatures in that day before air conditioners or electricity to run fans, however, soon took a backseat to another more pressing and disturbing problem of nature, the reappearance of a major outbreak of infantile paralysis, commonly called polio. Frightening outbreaks of the illness had long jumped and skipped across the nation like a capricious tornado, coming in the summer months and hitting cities and small rural communities, bringing heartbreaking destruction. Because of the tendency of the disease to erupt during warm weather, the illness was often called “summer plague.” [2]

Illinois newspapers began to pick up the story in early August, when a slight jump in cases occurred, scattered here and there across the state. A major outbreak had last struck Illinois in1917, and quarantining and sanitation efforts seemed to do little to control the fearful occurrence, until the disease disappeared with the summer heat in late September, leaving as mysteriously as it had arrived. Health officials in 1937 could only hope the situation would not worsen.

My father’s parents, Kermit and Ruby Mills, lived on a farm, operating an orchard and grain farming in a rather remote area in the northeast corner of Jefferson County, Illinois. Work kept them bone-weary, especially during the peach harvest from mid-summer through the fall, leaving them too tired to worry much about the sudden articles on polio now popping up in the newspapers. Perhaps too, they felt their area was remote enough to be a haven for my dad and his younger brother, Curtis.

Dad’s main work task involved bringing the milk cows in from the pasture for the evening milking, a job our hard-working Grandpa Mills sometimes thought was not carried out by his son with due diligence, the boy seemingly too dreamy for his own good.

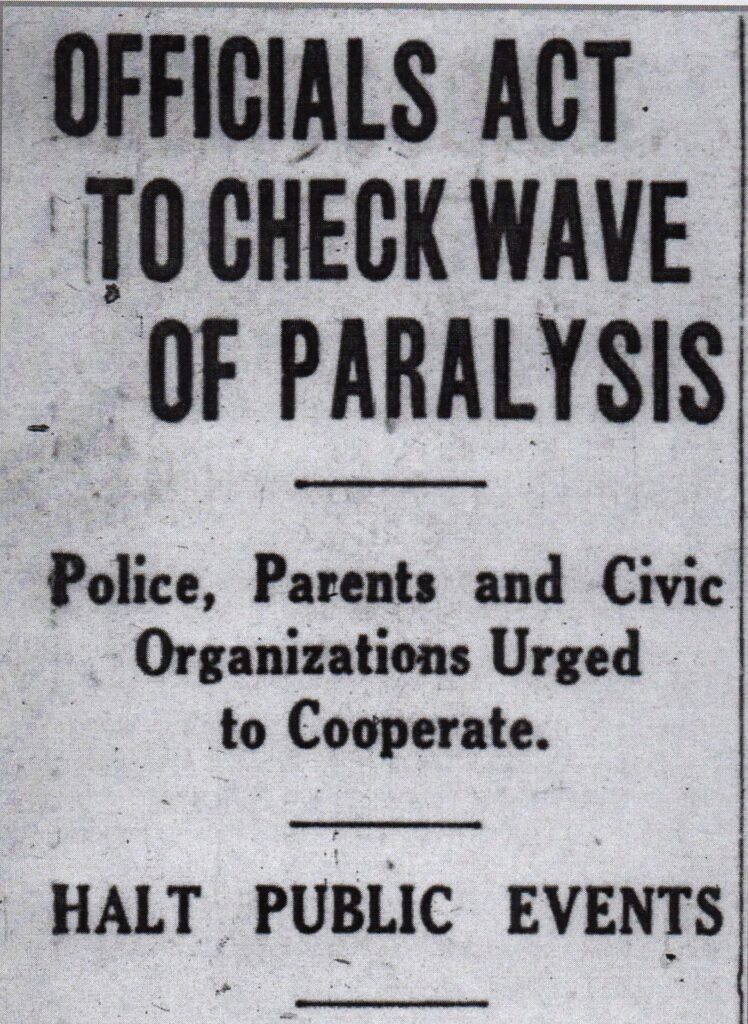

Scattered cases of polio began to grow into something more ominous, and the newspaper articles in late August of 1937 that reported increases in cases surely caught the notice of my grandparents. A Streator, Illinois, paper observed that the health officer there had issued a “warning over paralysis,” adding that nearby Bloomington had “six of these cases.”[3] A Mattoon paper declared that the speed of the rising cases was similar to the previous1917 outbreak. “Cases have occurred in all parts of the state,” the paper noted.[4] During this same week, the state’s health director announced that the disease was “more present in the state than in twenty years,” and further predicted an upward trend in the cases “until the middle of September.”[5]

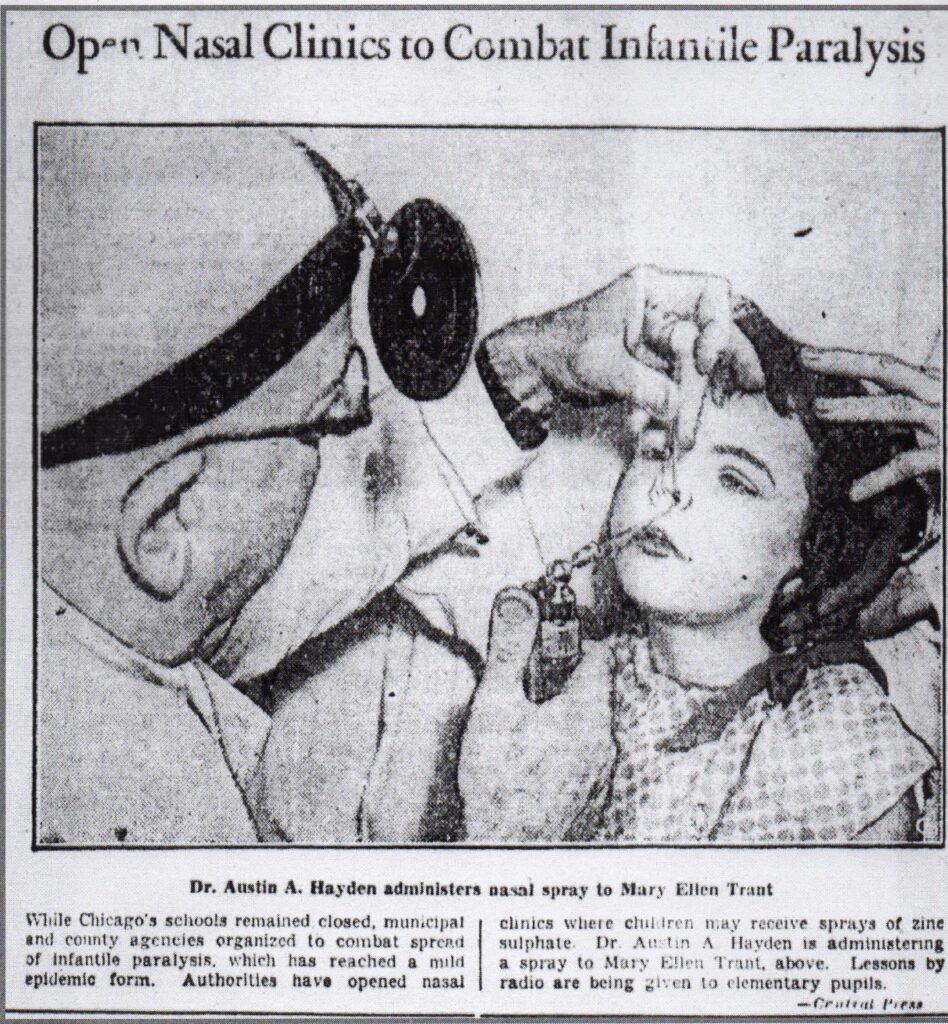

Believing wrongly that the virus entered through the nasal passages, doctors attempted to block the virus by swabbing zinc into the nostrils of children. One well-meaning expert wrote in his Illinois state newspaper column in early August, before the sickness became epidemic, “If I had a child in the area where infantile paralysis appeared, I would take him to a good nose and throat specialist and ask him to apply a spray consisting of 1 percent zinc sulphate.”[6] In some instances, the treatment permanently destroyed the patients’ sense of smell.

Once the cases multiplied, parents were advised to self-quarantine their kids, not ever letting them play with their neighbors. Across the state, newspapers sounded the alarm, explaining that there were no known effective treatments for the illness and that parents should keep an eagle eye out for symptoms—”sore throat, headache, stiff neck, stiff back or tendency to drop the head.” If these symptoms occurred, parents were encouraged to get blood serum for their child, a remedy that was later understood to be completely worthless. But even the doctors were grasping for straws once the situation became an epidemic. Anyone who had previously had polio, so-called “convalescents,” were encouraged to attend any statewide “clinic” in their area where they could give blood to make what was in fact a useless serum. One Illinois newspaper reported at the height of the 1937 outbreak there how “Thirty-one infantile paralysis convalescents responded to the state’s call for blood Tuesday and sold approximately 16 pints which will be used in the making of serum to fight the infantile paralysis epidemic in Illinois.”[7]

Nothing stopped the epidemic. The cases continued to quickly mount, and Illinois became the epicenter of the outbreak in the Midwest.[8] Soon there existed a shortage of iron lungs, “that scarcity becoming more serious since the recent outbreak, particularly in Illinois.”[9] By early September, Illinois headlines were more dire than ever—“Paralysis Wave Continues With 25 Fresh Cases; Opening Of Chicago Schools Postponed; Baby Dies Of Paralysis On Way to Hospital; Ashton Safeguards Citizenry Against Infantile Paralysis By Closing School, Churches.”[10]

The state health director, Dr. Frank Jirka, urged calmness, claiming people were moving to an unnecessary “state of hysteria” over the outbreak.[11]

Hysteria or not, the fierce disease was about to fall on my father.

My grandparent’s peach harvest was in full swing in late August of 1937, and they had their hands full. It was hot and sultry, with occasional puffs of light wind that were nothing more than frustrating teases. Peach pickers, their clothes dripping sweat, wrestled baskets into the large shed just across the road from the family house where the peaches were prepared for shipping by other work hands. To add to the turmoil, Grandma’s sister, Ruth Holloway, and the rest of the Holloway family were also visiting from New Mexico at that time. As pressure grew to get the peach crop in, Grandpa Kermit’s patience all but disappeared.

One afternoon, Grandpa asked my dad why he had yet to get the cows from the pasture. Dad complained that his legs hurt, and that he was so tired he could hardly walk. Grandpa gave him a couple of whacks on the legs, a light but humiliating whipping. Dad went out to get the cows, tears in his eyes, one strap of his overalls hanging off a skinny sun-browned shoulder.

With all the ongoing commotions in the orchard and the peach shed, no one noticed Dad’s longer than usual absence.

Dad finally struggled home and that evening grew sick with a high fever, unable to swallow or move. The family doctors, father and son Andy and Marshall Hall came rushing from Mt. Vernon as quick as they could. Grandma was crying and wringing her hands, praying she would not hear that dreadful word pronounced over her twelve-year old son by the two doctors. Grandpa was all but sick, shamed with guilt for having spanked his son.

The word was nevertheless spoken, and the world of my grandparents shaken to its core.

The prognosis was dire. Of all the degrees of polio, my father had contracted the bulbar type, one of the most feared and severe. The part of the brain affected by the polio virus with this form of the disease made breathing and swallowing immensely difficult so that the patient was left all but “drowning in their own secretions.”[12]

The older doctor, Andy Hall, who had been the state’s health director at one time and had seen many cases of polio through the years, knew how this type of the illness typically played out. Although he was very close to the family and to my dad, he gauged it would be best to stay in a strict professional mode, the better to guide the Mills family in what he thought would be the best path in the bleakest of situations.

Dr. Andy advised my grandparents not to send my father to a hospital, instructing them instead to keep him at home, quarantined with round the clock caretakers to keep his throat passage clear so he would not suffocate. Both father and son doctors sadly told my grandparents that my father would likely not live.

Dad could not talk and mostly lingered along in fitful sleep in a side room of the house. What little he ate passed thought a feeding tube that was stuck up his nose.

Grandma was almost dysfunctional, watching her son struggling to live. Grandpa was overcome with guilt.

It was Aunt Ruth, Grandma’s oldest sister, who stepped up. She agreed to be quarantined with Dad and along with a few other family members, all working around the clock to keep Dad’s throat clear.

There was nothing else for the others to do except return to work, but Grandpa Mills came in every night and sat by Dad’s side. Grandpa knew his son probably could not hear or understand anything of what was said, but he still spoke the same words, like a mantra, every night before he left his catatonic son and the sour smelling room—“Keith, I will give you anything if you will just get well.”

Day in and day out, the watch over Dad was long and tedious, Ruth routinely placing her fingers down Dad’s throat to remove the phlegm, probably saving her nephew’s life on an hourly basis.

Once Dad bit down on Aunt Ruth’s finger so hard, she screamed, the sound easily traveling out to the peach shed and beyond. Grandma assumed her son had died and went charging to the room where he lay, expecting the worse.

Two weeks later, Dad finally took a few spoonfuls of broth by mouth, his throat no longer paralyzed. After he had gotten down two shallows of the greasy liquid, he looked up weakly from his bowl at my Grandfather Mills and weakly spoke his first word since the onset of the polio attack.

“Chevy”[13]

[1] The McHenry Plaindealer, September 2, 1937.

[2] For a detailed account of the story of polio in America see David M. Oshinsky, Polio: An American Story: The Crusade that Mobilized the Nation Against the 20th Century’s Most Feared Disease. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

[3] The Streator Times, August 31, 1937.

[4] Mattoon Journal Gazette, August 24, 1937.

[5] Freeport Journal-Standard, August 24, 1937.

[6] Dixon Evening Telegraph, August 14, 1937.

[7] The Decatur Herald, September 29, 1937.

[8] Woodstock Daily Sentinel, August 4, 1937.

[9] The Decatur Herald, September 24, 1937.

[10] The Moline Dispatch, September 8, 1937; The McHenry Plaindealer, September 2, 1937; Chicago Tribune, September 2, 1937; The Ashton Gazette, September 2, 1937.

[11] Murphysboro Daily Independent, September 4, 1937.

[12] Tony Gould, A Summer Plague: Polio and its Survivors. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995, 163.

[13] I am so grateful for the work of my sister, Karen Mills Hales, in gathering up this story and many others about where we grew before these stories were forgotten and lost to the world. For more on the story of Dad’s polio adventure, see her book, We All Drank from the Same Dipper, Poplar Bluff MO: Stinson Press, 2004.