Randy Mills

There are many unsung heroes who were deeply involved in the early nurturing of Oakland City College, but perhaps none of these has been lost in the shadows of time to the same degree as Ella Wheatley. She was an important and constant presence for over four decades at the college, but there was one aspect of her earlier life shrouded in mystery. Photos of her in college yearbooks presented a serious, sometimes sad looking woman. Most would have probably thought her to be something of a lonely schoolmarm, unaware of Ella’s interesting and intense personal journey that earlier brought her bad love, and then, tragically, lost love. Her story further lends helpful insight concerning the vocational limits that young women faced in those times. To better understand this forgotten aspect of Ella Wheatley’s life, one needs some historical context.

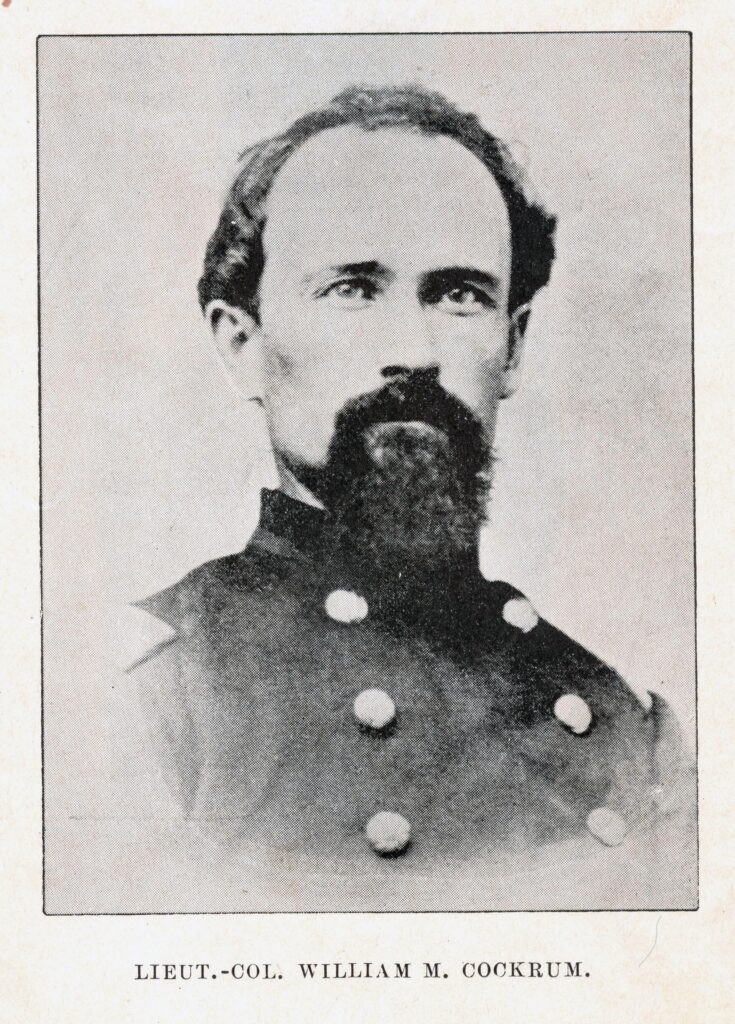

Ella Wheatley was born June 3, 1859, the second child and first daughter of William and Lucretia Cockrum. She was certainly born into a busy and oftentimes exciting household. Her parents were prominent in Oakland City and in the southwestern Indiana region. They were especially strong proponents of education, the latter an unpopular sentiment at that time in the state. Ella’s grandfather who lived nearby, James Cockrum, had been one of the founders of Oakland City, and together with William Cockrum, had been secretly involved in underground railroad activity in the 1850s, a dangerous effort given the pro-south and anti-black attitudes of the region.

In 1861, twenty-five-year-old William Cockrum left his family to serve in the Civil War. Ella would have been less than three-years-old when her father left. The next four years witnessed much trauma— Ella’s father’s furlough visits were few and short-lived; two of William’s brothers died in combat; and Ella’s mother would have a set of twins a month after Ella’s father was severely wounded and then captured at the battle of Chickamauga in 1863. One twin, named after his father, died shortly after childbirth.

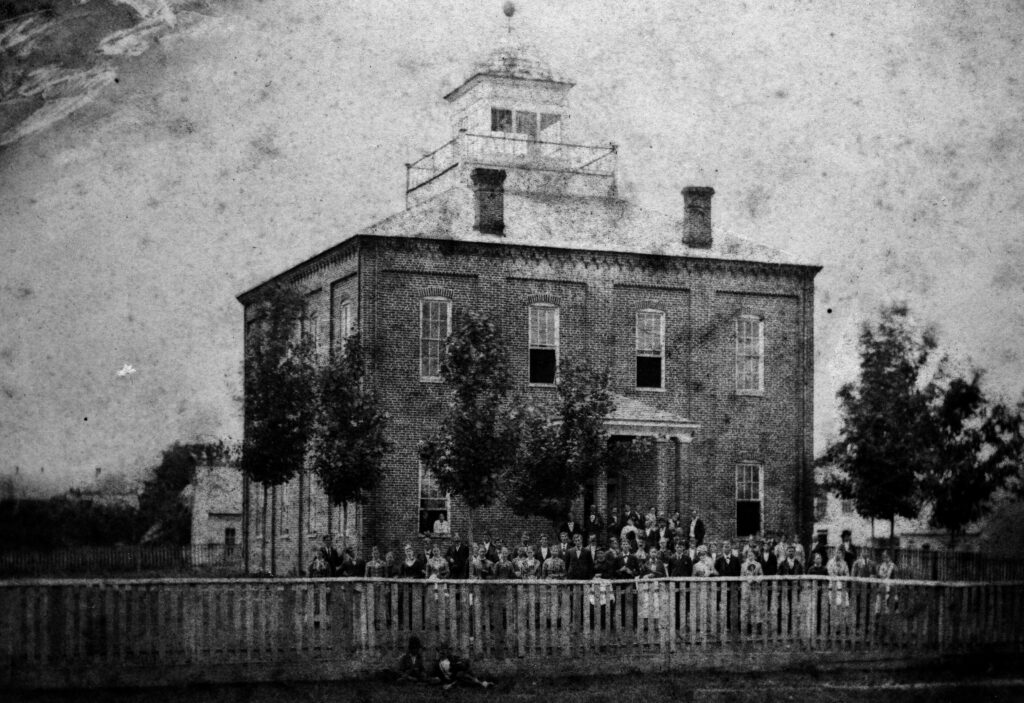

William Cockrum survived the brutal war and returned home in the spring of 1865. After his arrival, things turned more stable for the Cockrum family. Both James and William Cockrum continued to be rising stars in farming, business, church, social, and political endeavors. In 1867, for example, the two men started a college in Oakland City, the Oakland Institute, to help improve the skills of local teachers and to provide a classical education to any of the locals who wished to go to college. In 1875, a Princeton newspaper reported the college was “going full blast with at least 115 in attendance and out of that number, 76 are schoolteachers.”

Ella, who would have been sixteen years of age in 1875, was on the cusp of young womanhood, and the college environment that surrounded her offered a much richer cultural experience than a young girl in the region would have normally experienced. This included having the opportunity to hear of the latest scientific, political, and religious discourses and to be able to attend public art and musical presentations. Unfortunately, Ella’s life was about to grow more complicated.

In 1874, James and William Cockrum spearheaded a temperance movement in their immediate area, going so far as to violently destroy legal saloons in several nearby places, including a legal saloon in Oakland City. Ella was sixteen years old when the destruction of the saloon in her hometown brought horrible retaliation upon her family.

One February night in 1875, in the wee hours of the morning, the William Cockrum home was firebombed by unknown attackers. The family barely escaped as the house blossomed into flames and burned to the ground, Ella and her siblings running in bare feet away from the catastrophe. It was thought that the brutal assault was reprisal for the vigilante destruction of the Oakland saloon, and the attackers were never identified. The shock of this event may have also led to the deaths of Ella’s elderly Cockrum grandparents, who both died shortly after the firebombing. And if these two events were not awful enough, with James Cockrum’s death, the college founded by Cockrums failed, the college building sold to the town, with only a yearly teacher’s institute still taking place there.

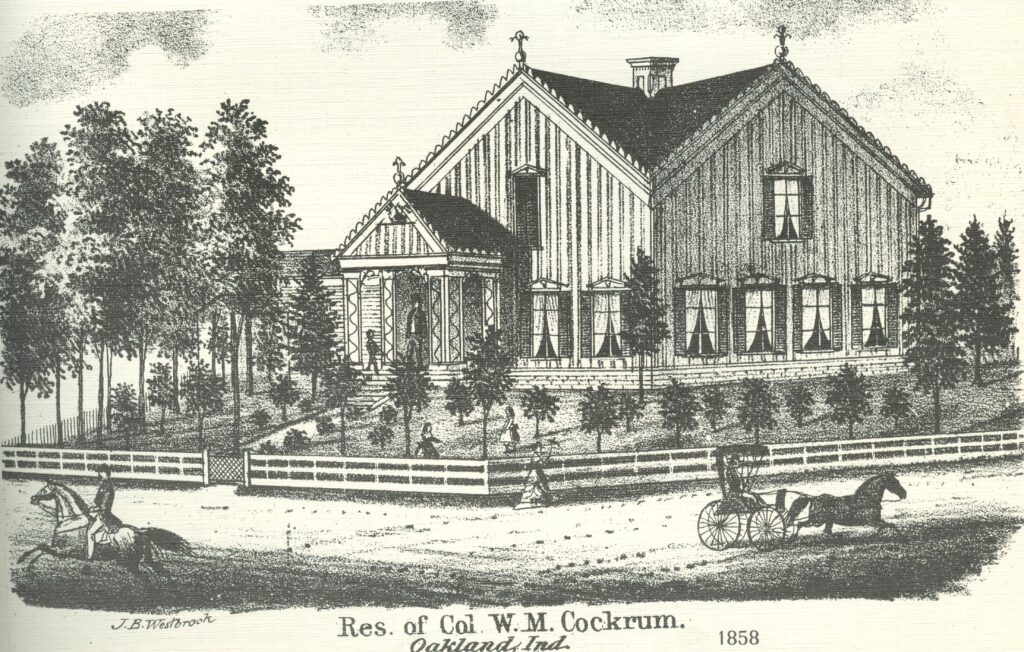

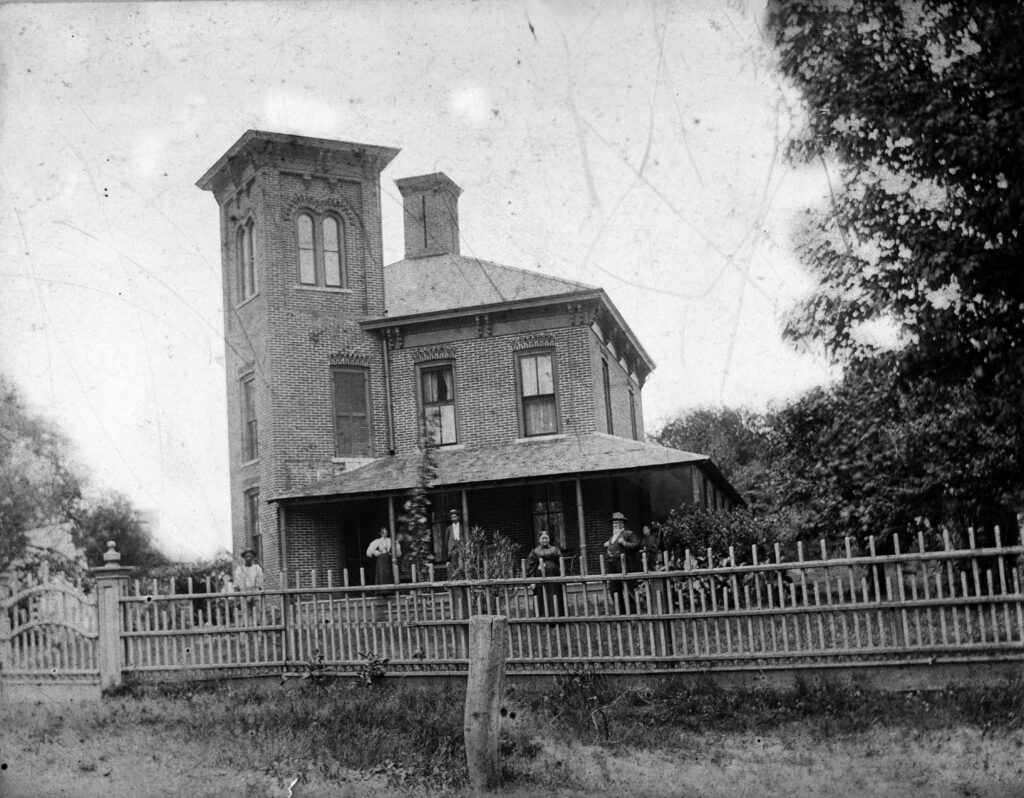

William Cockrum did not let these setbacks deter him. He quickly replaced the firebombed house with a beautiful and spacious two-story brick Italian Villa style home with a three-story tower that became a regional showpiece. William and Lucretia’s oldest son, John, two years older than Ella, was a helpful part of the Cockrum family’s rise from the ashes, being a budding law student. For Ella Cockrum, life went on too, as she faced the question of her own future as a young adult woman. Like her older brother, she too was expected to do well. Vocationally, however, she had two choices. If Ella remained unmarried, she could look forward to attending Indiana University and the local teacher institute and becoming a schoolteacher. The other possibility, however, was what she wished for. Ella yearned to find a kind and ambitious husband and have a family. This too was a highly prized path for a young woman at this time and place, and in Ella’s life that person soon took the form of a Lynnville, Indiana, man named John T. Thompson, an acquaintance of Ella’s lawyer brother.

John Thompson seemed a sophisticated match for Ella. He began gaining newspaper recognition in January of 1874, when the Boonville Republican noted he had studied enough under a local lawyer “to be admitted to the Warrick County bar.” In late June, the Boonville Weekly Enquirer reported that the young Thompson had been elected as secretary for planning the Lynnville Fourth of July celebration. Late that summer the same paper printed a longer report about the rising star of Lynnville, noting his ambition of becoming a great lawyer. “Our young friend, John T. Thompson, left us on Thursday for Greencastle (DePauw College), where he designs entering the law department of the college for the purpose of thoroughly preparing himself for the practice of law.” The article further praised the young man as being “of bright, intellect, a close student, and should he continue as he has started out, he is destined to arrive at high eminence in the profession of the law.” The reporter lamented that the Lynnville community “regretted to part with him, as his society will be missed from us for the time being.”

In 1876, a year after the Cockrum fire bombing, Thompson again left Lynnville and moved to the Warrick County seat of Boonville, to be closer to the legal action. The Lynnville reporter to the Boonville paper noted, “We regret his departure from town but congratulate the citizens of Boonville and especially the members of the bar on his accession to their ranks as he will certainly be an honor to the profession as well as a worthy citizen.” It was in Boonville that John T. Thompson came to know another young lawyer practicing law there, John Cockrum.

By August of 1876, Thompson had joined an established lawyer to create the firm of Taylor and Thompson. For one so young, Thompson quickly began to develop a reputation for speaking at political and social events. The Boonville Enquirer reported, for example, that he made “a respectable little speech” at one political gathering in the county, “and will in time make a mark as an orator.”

In 1877, the Enquirer featured Thompson and his law partner, John Taylor, in an article, noting that the two “engaged in professional business and enjoying the social company of their numerous friends. The two young attorneys are happy to learn, are working their way into quite a lucrative practice and will make shining stars in their profession.” Secretly during this time, however, Thompson was talking with John Cockrum about joining him in a law practice. In these talks at Cockrum’s Boonville home, Thompson had met Cockrum’s sister, Ella. There was an almost instant mutual interest.

William Cockrum was appropriately concerned about his first-born daughter’s romance, not quite knowing what to make of the smiling, confident young man from Lynnville. Still, he was able to check out Thompson’s talents at a Fourth of July celebration at Perigo Grove in Warrick County, where he and Thompson both spoke under the shade of several large oak trees. The shade, however, was of little help, the temperature, according to one newspaper, just shy of one hundred degrees when the two men spoke. The same Boonville newspaper touted both men’s speeches as “highly credible efforts. . . . Suffice it to say that the speeches indicated careful presentation, earnest study, and a high order of intellectual power on the parts of their authors.” Ella Cockrum sat in the audience, uncomfortably hot, but still beaming.

The engagement of Ella Cockrum and John T. Thompson in 1877 was the talk of the immediate region of Gibson and Warrick Counties. Thompson’s father, Captain D. R. Thompson, was a local tobacco grower and merchant in Lynnville and was, like William Cockrum, a venerated veteran of the Civil War. Both men had served together in the Indiana Forty-Second Regiment. Captain Thompson, however, injured his health while serving and never completely recovered. Overall, John Thompson had the most to gain socially in the marriage, as both Colonel Cockrum and, to some extent, his lawyer son John Cockrum, had important political pull and were highly respected.

Newspapers carried stories of the upcoming marriage and the ceremony as if it involved royalty. The week before the September 26, 1877, wedding, Ella and her family were “hosted by Captain D. R. Thompson at his residence in Lynnville.” The wedding itself was the first official social occasion held in the newly built Cockrum mansion in Oakland City. A Boonville paper observed of the major social event, “On last Wednesday, the 26th, of September, the long talked of and long looked for marriage of John T. Thompson Esq., of Boonville to Miss Ella Cockrum, daughter of Col. W. M. Cockrum, took place at the residence of the Colonel, in Oakland City, with all the pomp and circumstance characteristic of modern style high life. The attendance was quite large and intellectual in the highest degree.” The entertainment that followed the wedding was said by the paper to be “so brilliant and magnificent that we feel ourselves entirely too inadequate for the task of giving even a faint description of it.” The piece ended by wishing the special couple “a long life, happiness and all the rich blessings of the earth.” The Princeton, Indiana, newspaper too spoke of the sophistication of the wedding with its “bountiful food and the elegant strains of music” which followed the marriage ceremony. The Cockrum parents, the paper went on to say, “will be long remembered by many friends for the impressive day.” Even the General Baptist Herald got into the spirit of celebration, reporting that “after the ceremony, the guests were ushered into the beautiful dining room where one hundred and three people partook of a sumptuous meal.”

By early the next year, 1878, John Cockrum and John Thompson were working together in their law firm, and Ella entertained frequent visitors in her new home, as her husband continued to be, in the words of one newspaperman, “a good attorney and a gentleman with all.” It is unclear in the newspaper accounts that could be found in this research as to how things began to fall apart for John Thompson. This much is known—by September, he was advertising in newspapers as practicing law without a partner, his office, “Over Wm. Kinderman’s Store.” The real shocker, however, came in December of that year when newspapers told of his arrest. The Princeton Clarion-Leader reported, for example,

John T. Thompson, one of our young attorneys, was arrested Monday morning last and taken to Evansville, by a United States Deputy Marshall. Thompson was assignee in bankruptcy of the firm Hemenway & Johnson and had collected money and failed to turn it over to be proper authorities, and an indictment was found against him by the United States Grand Jury at Indianapolis, hence his arrest. His bail was placed at $1,500, but up to this writing, he had not secured bail, and was under the guard of the city.

By July of the next year newspaper accounts showed Ella was living with her parents in Oakland City. Ella soon after sued for divorce, a rare occurred in those days, taking back the Cockrum name. The specifics of the divorce were also printed in the local paper so that readers could see in detail how she had little choice in the matter and was not in any way at fault, a situation that needed to be made clear to the public if Ella were to have a future. The report also gives strong clues as to what went wrong and why it happened so quickly.

Ella Thompson was granted a divorce from John T. Thompson, on a complaint charging him with cruel and inhuman treatment, failure to provide, habitual drunkenness, neglect, gambling, laying out of nights, visiting houses that ought to be shunned, especially by young married men, and generally sowing the modern variety of wild oats after his season for such work has long since closed. The plaintiff resides at Oakland City, and the defendant in Boonville, Warrick County.

The article suggests what likely drove Thompson’s dramatic downfall—alcohol. It also reflected that time’s lack of knowledge concerning an understanding of alcoholism as a disease and the hope of recovery through modern-day twelve-step type programs. Still, what an awful heartbreak and embarrassment this must have been for Ella, and for the Cockrum family who had risked their very lives fighting saloons. After the divorce, John Thompson all but disappeared from the newspapers, save for one odd courtroom account in 1881 where he served as the prosecuting lawyer in a lowly Justice of the Peace setting. Perhaps too, the embarrassment Thompson caused his own family brought a relatively early death to his father who died suddenly in 1882. Meanwhile, Thompson’s drinking habits took their toll. In 1884, he died suddenly, and one local paper used his death to make a moral statement.

The news of the death of John T. Thompson will be read with genuine regret by many of our citizens. Six or seven years ago there was not a young man in the country with brighter prospects than John Thompson. A fair law practice, good social standing, robust heath, and a host of friends. And this is the end!

After her divorce from John Thompson, Ella Cockrum spent time at Indiana University, studying English and literature so she could come back to her home area to teach. Teaching meant she would not marry, which probably suited her just fine after the John Thompson debacle. In 1880 she taught at a rural school far enough away from Oakland City that she had to board away from home, dealing with rambunctious rural children and learning the hard way about the dynamics of maintaining a potbellied stove. She also began attending the annual Oakland Normal Institute in Oakland City for rural and small-town teachers. While these things were happening for Ella, her father also began a new project, trying to restore the prior liberal arts and teacher’s college he and his father had founded in Oakland City 1867. This time he had the support of the General Baptist denomination, a group which hoped to have a seminary as a department in the college. In 1885, these efforts brought a charter for a college from the state, but the school had many obstacles to overcome before it would hold its first classes in 1891. The school was destined to be an important part of Ella’s life.

Meanwhile, by 1885, Ella had garnered a prime teaching position in the Oakland City school system and was living with her parents. It had been several years since her divorce, and Ella may have felt she was an older and wiser person, prepared not to fall in love again. That same year, however, a new principal in nearby Francisco, Winfield Scott Wheatley, was one of the two directors of the teacher institute, and he immediately caught Ella’s attention. Wheatley was a scholarly man, well-traveled, as he had worked researching and writing county histories for the Goodspeed Publishing Company of Chicago. He was a year younger than Ella. One newspaper noted he was “A thorough gentleman and a man of decided literary tastes. . .. He lives among his books.” Two years later, he would be living, in the words of the same newspaper, “in the love of his estimable wife, Ella.”

Ella and Scott Wheatley’s wedding in 1887 was much simpler than Ella’s marriage ten years before to John T. Thompson. A Boonville paper simply observed that “Prof. W. S. Wheatley and Miss Ella Cockrum, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. W. M. Cockrum, will be married at the residence of the bride’s parents on the 20th inst.” The Princeton paper also reported the couple would be leaving their teaching positions and “be engaged in a work, the fulfilling of which will enable them to travel over considerable of the south.” In fact, the couple would be traveling throughout the south while working for the Goodspeed Historical Company, interviewing interesting people, gathering research, and writing county histories together. Having a partner as an equal, one she could share her intellectual ideas with was a dream come true for Ella. Tradition has it too that the couple eloped before the wedding, Ella’s sisters using a sheet rope to help lower her down from the second story of the Cockrum house into Scott Wheatley’s waiting arms and on to Arkansas for their first work assignment together. If only life were fair. Eleven months later the Princeton paper carried a grim report:

Prof. W. S. Wheatley, a well-known teacher of this county, died at Fort Smith, Arkansas, on last Saturday. Mr. Wheatley was married to Ella Cockrum, daughter of Col. Cockrum last October. The wife of less than a year started home with the remains yesterday and was met at St. Louis by G. M. Emmerson and Col. Cockrum, who passed through Princeton today in route to Oakland City where the body is to find its last resting place. Mr. Wheatley was without a vice, and the world is poorer today.

As Ella Wheatley struggled to get past the shock of her husband’s unexpected death, she found some solace in throwing herself into helping her father in his efforts to keep alive the fledgling Oakland City College. Ella’s work soon became a lifetime career. Her contributions to the school would be many, as she came to dedicate her life to the institution. In 1892, she donated her house for the first woman’s dorm, a house that was renamed Wheatley Cottage. In 1895, after graduating from OCC and taking classes at the University of Chicago, Ella became the first women’s dean at Oakland City College and a professor of English language and literature. Eventually, a much larger “modern” women’s dorm would be built in 1911 and was named Wheatley Hall in Ella’s honor. As women’s dean, Ella Wheatley would oversee the lives of hundreds of female students who came to Oakland City, and her namesake, Wheatley Hall, would continue to be a home-away-from-home for female college students for decades after Ella’s death in 1943.

As noted, one early Oakland City College yearbook faculty photo of Ella is interesting, as it shows a sad-faced woman with a far-away look in her eyes. Interestingly too, few, if any, at the college would ever know about Ella Wheatley’s earlier experiences with love. However, these stories, shared here for the first time, reminds us that peoples’ lives are complicated and rarely dull, full of unexpected and often difficult events and adventures. They are, in fact, important stories to be remembered and cherished by individuals, families, and by institutions.