There is at least one unconfirmed story out there about Jesse James and his gang spending time in Farrington Township in Jefferson County, Illinois, an area commonly called Horse Creek. My sister Karen Mills Hales, related the undocumented story in her book—A Place Some Call Home: Stories from the Horse Creek Region of Southern Illinois. More recently, Jim Knauss contacted me about the account and sent a portion of a 1976 article from the Mt. Vernon Register News which also referred to the tale, asking me if I thought the story might be true. He made a good argument to me for the story being authentic. “Considering that the Goshen road ran nearby, you can’t rule it out. After the Great Northfield robbery (in 1876 in Minnesota), the James brothers ended up in Nashville which could have easily taken them through Farrington Township.”

Unfortunately, I have not been able to find any official documents or old newspaper accounts supporting this possibility. However, in my gathering of material for a book on the forgotten four decades of violence from 1880-1920 in the Horse Creek region of southern Illinois, I did come across the unusual story of the two leaders of the notorious Reeves outlaw gang that did escape to the Horse Creek area to hide out at the end of the nineteenth century. One national newspaper called them “the last Jesse James-like gang in the country.” As a side note, I lived for fifteen years in the region of the Reeves gang’s plundering in Indiana, and traveled many times past the place where they murdered two Dubois Indiana county deputies. Odder still, the place where the Reeves men were captured in Illinois was the home of one of my ancestral relatives. Small world.

I present the story of the Reeves gang here, not quite the James gang, but just as dramatic. Narratives in quotation marks come from a variety of regional and national newspapers.

*********

In 1896, newly arrived brothers John and George Clark began selling merchandise from a wagon in the remote Horse Creek region of southern Illinois. The middle-aged men were completely close mouthed when it came to explaining anything about their past, and it seemed a bit odd to some that the two entrepreneurial brothers would settle in the Horse Creek area in the first place. The Horse Creek community was considered a backward, exclusive, sometimes violent frontier-type region, spanning the southeast portion of Marion County, all of Farrington Township in northeast Jefferson County, and a small part of Hickory Hill Township to the southeast in Wayne County. Trading with the clannish people there would not be easy.

But the Clark brothers apparently had charm, or, more likely, came from a similar place and knew how to fit in, and their enterprise soon seemed to be thriving. Eventually, John would marry a nearby Centralia girl and move there. George Clark was more comfortable staying in the heart of the Horse Creek district, “living with the William Byars family on the banks of Horse Creek,” according to one newspaper account.

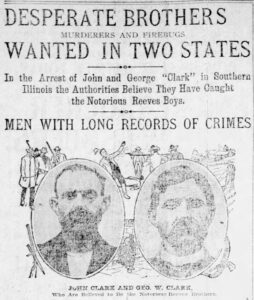

By early 1900, Jefferson County Illinois law enforcement began to suspect that John and George Clark were not the good citizens they seemed to be. Suspicion arose when rumors began to circulate that the items sold from the Clark brothers’ peddler’s wagon were sometimes stolen goods. At first, Jefferson County Sheriff Tom Manion hesitated to investigate the matter, the two Clark men being “held in high esteem.” Finally, Manion’s initial instincts won out, and he began seeking information from law enforcement in the region, asking about anyone matching the description of the Clark brothers. A response quickly arrived by telegram from Kentucky, telling him all about two brothers named George and John Reeves. A Montana newspaper later reported of the gang’s disturbing history, “Twenty years ago [1881], John and George Reeves went to Dubois County [Indiana] from Terre Haute. They settled in the hills of Columbia township and organized the Reeves gang of ten or a dozen members that terrorized the whole neighborhood. Robberies of stores, houses, and barns, [plus] highway robbery and numerous petty crimes were committed by the gang.” This description, as it turned out, was just the tip of the iceberg.

The father of the Reeves boys, Robert Reeves, was a doctor who already possessed a criminal history before he came to Dubois County Indiana in the early 1880s. His illegal activities may have been why his first wife, mother of George and John, divorced her husband in 1869 while they lived in Terre Haute. The Indianapolis News reported in 1878 that “The trial of Dr. Robert Reeves, living in the vicinity of Seymour, on a charge of having counterfeit money in his possession, and selling it, is in progress in the United States court.” This case had come up in 1876, but Reeves was already serving time for a similar crime, having operated a counterfeit scam in the Martin and Orange county areas earlier.

Upon his release from prison in 1883, Doc Reeves returned to southern Indiana, staying with his second wife and her people in Columbia Township in Dubois County. Here, he traded “a team and wagon for forty acres of land … not generally working much it is said but living well.” A lost traveler, a new local teacher, stumbled across the Reeves homeplace just after Doc Reeves had arrived and found an odd notice posted in a bold hand on the structure’s front door: “I have just bought this farm and paid for it. I want my neighbors to keep off this place and quit stealing my fence rails—REEVES” The note suggested that the elder Reeves was not one to be crossed.

Doc Reeves could not have found a more remote place in Indiana in which to live. The northeast corner of Dubois County touched the territory of the notorious Archer gang in Lost River Township, just to the north in rugged Martin County, and the hills and valleys of Orange County to the east were where Reeves had previously worked his counterfeit game. His new home was a hilly landscape of caves, sink holes, beautiful flowing springs, and curious monolith formations, such as Raven Rock and Hanging Rock. Having lived in Martin and Orange counties before, Reeves knew that the steep scenic hills and deep gorges and dark valleys of the region offered a number of places where secret activities could safely be carried out. It helped in this latter case too that there were no towns with strong law enforcement elements, only tiny villages like Hillham, Ellsworth, Cuzco, and Kellerville, small communities built around a post office, a general store, a livery stable, and a few other small businesses.

Local and county law enforcement in Columbia Township was further hampered by the complex web of kinship loyalties found there, and county law officials were often unable to arrest someone from the area for a lack of knowing the lay of the land, leaving the general population to deal with those, like the Reeves family, who committed petty crimes. One local newspaper reported in 1879, for example, how two Dubois County deputies sent into Columbia Township on “a lively chase for some fugitives were chased away by an angry woman “for shooting at her boy.”

The two Reeves brothers, George and John, had been in the Columbia Township area off and on since the mid-1870s, and in 1884 they joined their father there permanently, helping the elder Reeves “sow a patch of oats.” George, at thirty-five, was the oldest and stood almost six feet tall. John was a bit shorter and five years younger. Both young men were well built and had dark hair and complexions and wore long dark mustaches. The latter feature gave them a distinct bandito look.

Much of the time the brothers were restless and unemployed. They did have hopes and plans, however, to purchase their own wagon and go into the peddling business one day in an area north of Terre Haute where relatives lived. Unfortunately, this dream was just out of reach, as they were always short on cash. This may have driven them to turn to petty crime to raise money for the new venture. Apparently, they discovered crime paid, with one Dubois County neighbor later observing, “I never saw either of them work a lick in my life.”

The Reeves brothers must have had some commanding presence about them, as they were able to quickly assemble at least six gang members from the Columbia Township area to help steal and move horses. “They were all married men,” one newspaper later reported, “and most of them raised in the neighborhood, but were willingly led to rascality by such tutors as the Reeves.” The brothers could now tap into the elaborate kinship system in the area, one that shielded them to a degree from probing law enforcement people. Known and respected for their quick use and accurate aim with pistols, the Reeves boys may have also possessed another method of persuasion, that of doing whatever it took to get what they wanted and to protect their outlaw business. Earlier, they had “shot four men who were attempting to arrest them in Orange County” and escaped, this at the time their father was running a counterfeit racket there in the mid-1870s. By 1885, newspapers often reported of horses “supposed to have been stolen by the Reeves Boys.” These actions and others would soon make the brothers, “a terror to the people in that part of the country.” The two Reeves brothers’ increasing activities would eventually converge in a way that would lead to a deadly encounter near the Dubois County seat at Jasper, one that would bring violent deaths to two law enforcement officials and completely reshape the outlaw brothers’ lives.

In early June of 1885, Doc Reeves journeyed to Jasper, Indiana, to pick up a new wagon he was buying his sons so that they could finally leave the area, escape from an arrest warrant hanging over them, and begin a peddling business near Terre Haute. The warrant went back to an episode in 1883 when the brothers robbed a store in Martin County. They posted bail but never showed up at court. A warrant was issued for their arrest, but law enforcement found it difficult to seize the brothers, fearing their impulsive behaviors. Dubois sheriff Joseph Hoffman, who knew Doc Reeves, having traded for horses with him, confronted John Reeves in a garden patch by the Reeves home but had made the mistake of going there alone. Reeves drew a gun on the sheriff and hollered, “Hoffman, god damn you, get out of here.” Hoffman quickly mounted his horse and retreated to Jasper.

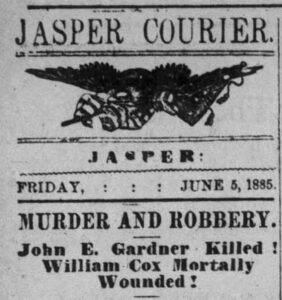

By 1885, a new Dubois County sheriff, George Cox, wanted to get the Reeves arrest warrant off his list. Cox was especially desperate to capture the two hoodlums, as they had long been successful in committing crimes while hiding in the wilds of northeast Dubois County, and to the north, just over in the hills of Martin County, giving law enforcement a bad name. Hearing that the elder Reeves was coming to the county seat of Jasper to buy a new wagon, the sheriff, “thinking the Reeves boys might be hiding near the town, and would join him on his way home, sent his deputies, John Gardner and William Cox, to follow the old man.”[xiv] William Cox was the sheriff’s son.

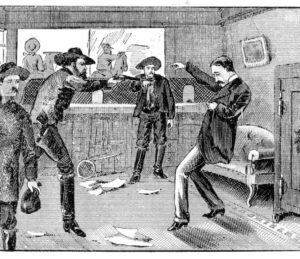

A half-mile east of Jasper the Reeves brothers came out of their hiding place and got into the new wagon driven by Doc Reeves. The two deputies, on horseback, had meanwhile slipped up on their prey near the Schroeder schoolhouse, taking the bandit family entirely by surprise. When called upon to surrender, the Reeves men “meekly did so.”

Then, everything suddenly went to hell. One paper reported, “Cox nor Gardner knew the Reeves well at that time.” To make matters worse, the paper explained Deputy Gardner had been drinking, “and in addition, was a great braggart and fond of showing his bravery and prowess in spite of their reputation.” Gardner was especially vain about a fancy pistol he carried, flashing it around and telling “the brothers that he was not afraid of them.”

As the deputies and their prisoners began their march back to Jasper, Doc Reeves noticed the handsome pistol Gardner had sticking out of his pocket and remarked on its beauty. “The deputy handed it to him to look at and said there was none better. The old man passed it over to John, his son.” John Reeves immediately opened fire, shooting Gardner in the head then turning the gun on Cox, “whose horse had reared. The first shot struck Cox in the wrist, knocking the gun from him. the second in the chest.” The deputies were now disarmed and wounded, having not fired a shot.

George Reeves picked up Cox’s revolver and walked over to where the bleeding Gardner lay, begging to be allowed to live a few hours longer. Reeves told him, “Dead men tell no tales” and placed the barrel of the gun between the deputy’s eyes and pulled the trigger. Then he shot Cox in the lower back, severing his spine. Gardner died within a few hours, but not before telling several people, “I foolishly let the boys get my pistol.” Cox lingered for several months, paralyzed, before “finally dying of his wounds.”

Immediately after the shootings, as the two deputies lay in the gore of their own blood, Gardner’s head wounds leaking with each heartbeat, the Reeves brothers went through the pockets of the wounded men, finding nineteen dollars, which they took, along with the deputies’ horses and the handsome pistol that had started the tragic event. Taking the officers’ horses, the Reeves brothers soon whipped them into a sweaty lather, putting as many miles between them and Jasper as possible. Doc Reeves took his team and new wagon and drove home another way, taking an unfamiliar route to avoid the law, his efforts to get his boys away from the arrest warrant and into a new life of peddling blown to pieces.

After the shooting, John and George were able to sneak back to their father’s house near Hillham before their father arrived home. They soon left, as night gathered, telling their stepmother to have their father meet them nearby for a difficult cross-country twenty mile trek to Huron, a small village deep in the hills of Martin County but on a railroad line. From there, they could hop a train and get outside the local area, escaping to relatives in Sullivan County. The governor had placed a $700.00 reward for their capture and the woods was soon thick with men and boys searching for the fugitives. John remembered that once united, he and his two family members discovered “the woods were full of men hunting for us. We were surrounded two or three days and were shot at several times. Father was shot in the leg. I saw the blood.”

Doc Reeves told his sons to go on and that he would try to get back to Hillham. The brothers did so, hopping a train and eventually making their way to Sullivan County, where they hid out at an uncle’s. What was left of Doc Reeves’ body was discovered in wild tangled countryside in Willow Valley, near Shoals in late June.

In March of 1886, the Reeves brothers secretly left their hiding place in Sullivan County and went by chance to Centralia, Illinois, where they worked in a machine shop that spring and in the strawberry fields in the summer. This quiet life, while safe, made the brothers grow restless, and they plotted a new course, going to Kentucky sometime in early 1887.[xx] Once in Kentucky, they evolved into more sophisticated thieves, developing an expertise in safe cracking and explosives and creating another gang, including two younger brothers. One newspaper reported that John Reeves “mastered every detail of safe construction. In order to successfully open safes, such as ordinarily kept in the store of village or country merchants, he needed only a diamond drill, a brace and bit, and a few pinches of powder.” The gang spent careful time sizing up places to rob and traveling great distances to get equipment and horses while creating elaborate ploys to set up safe blowing jobs. These changes heralded a move from petty local crimes to a new type of gang strategy—a more sophisticated operation taking in more money, moving through larger areas of strangers, and using the latest technology rather than crude intimidation to pull off robberies.

The Reeves’ efforts soon moved beyond Kentucky, the gang blowing safes in Dover, Jellico, and Celina, Tennessee, and at a small village in Alabama. But their biggest haul was from a safe in Tompkinsville, Kentucky, in late 1887, with the powerful safe explosion setting off a fire that burned down much of the town, including the courthouse. During this spree, the gang put away at least thirty thousand dollars.

After the big Tompkinsville haul, the Reeves brothers made plans to rob a Knoxville, Tennessee, bank, but were finally captured and taken back to Monroe County, Kentucky, to stand trial for the robbery and fire in Tompkinsville. The two brothers faced a bleak situation, having been sentenced to thirty-one years in the Kentucky state penitentiary for the Tompkinsville fire. And Indiana waited to try them for murder when their Kentucky term ended.

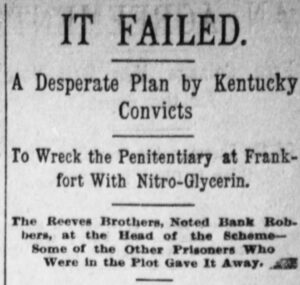

The Reeves boys did rather well in prison, or at least they kept busy. In 1890, they attacked and took a gun from a guard, “bound and gagged him, but were discovered before any mischief could be done.” After that, they “were regularly locked up in the dungeon on days when they were not at work.” When a new warden came, they were given more freedom, but soon plotted “to tunnel under the walls,” and the new warden placed them in solitary, regarding them “as the most desperate prisoners in the penitentiary.”

In 1893, the Reeves brothers hatched a more elaborate plan for escape, a plot the warden later described as “hellish,” after it was thwarted. With outside help, the Reeves brothers received and buried “three bottles filled with dynamite, one hundred rounds of cartridges and two pistols” under a shed near the warden’s house. The two convicts intended to use these materials “to either escape by killing the wall guard between the male and female yards, or by going through the main entrance as the gates were swung open for the passage of wagons.” Either attempt would have led to a bloody mess. Fortunately, another inmate revealed the plan to the warden, the deadly items were unearthed and removed, and the Reeves boys went back to the dungeon.

In 1896, a ruling by the Kentucky supreme court in September of that year, drastically altered the Reeves’ lives. Their original thirty-year sentence was dropped to ten years, as the court ruled the initial cumulative sentence to be unconstitutional. Their term would now be up on October 26, a month away. In any other circumstance, George and John Reeves would have been overjoyed. However, when Indiana authorities found this out, Hoosier governor Matthews issued a “requisition upon the governor of Kentucky for the return of George and John Reeves.” Dubois County authorities quickly arranged for Sheriff Cassidy to go to Frankfort and haul the Reeves brother back to Jasper, Indiana, where they would stand trial for the brutal murders of deputies Gardner and Cox and likely be hanged.

Two days before Cassidy left for Kentucky, a Reeves family member arrived at the penitentiary and told their kin of what was transpiring and, perhaps, brought money to bribe guards. At any rate, that night George and John Reeves scaled a wall of the prison, disappearing into thin air. They did leave a playful message for the warden, an almost illegible note that said, “Excuse haste and a bad pen.”

John Reeves’ 1901 testimony in a Dubois County courtroom indicated that he and his brother fled immediately from Kentucky and went to the remote Horse Creek community in southern Illinois, near the area where they had previously lived for a short while after the Dubois County shootout in 1885. Taking the name of Clark, the two fugitives boarded with Jefferson Simmons, who lived in the northern portion of Farrington Township. Here, the brothers finally got to go into the peddling business, likely finding their slow laid-back wagon trips through the wooded countryside wonderfully pleasant after ten years in prison. George was now fifty-one years old and his brother forty-six, both old enough to be slowing down.

Three years after coming to the region, John Clark married a nineteen-year-old woman from nearby Centralia, Illinois, Maud Dawkins, and the couple purchased a house east of that city. Her family was prominent, and “half the county was present at the wedding.” The couple soon had a child, and John began farming with his father-in-law while his brother, George, continued most of the merchandising work in the Horse Creek location, continuing to sell goods from a wagon. Jefferson Simmons having died, George now boarded with “the William Byars family on the banks of Horse Creek.”

It probably helped the two strangers’ anonymity that the Horse Creek people, and the Clark brothers shared a similar cultural heritage, that of the rugged upland south. Horse Creekers were not surprised or particularly upset when finding that someone was not perfect. In fact, there seemed to be a grittiness with the Clark brothers that Horse Creek people quickly came to admire.

While John thrived as a farmer and became a church deacon, George’s love of hunting and fishing, and his comfort with interacting with Horse Creek’s colorful frontier-like population made him bond with his rural neighbors. Perhaps too, the Horse Creek area reminded him of his father’s home in the remote hills of Dubois and Martin Counties. Indeed, Horse Creek had a similar reputation for violence, but these events were less about criminal gangs and more about resistance to authority, family feuds, and fights over honor and manliness. These violent episodes often brought state-wide and national newspaper attention, along with interesting headlines such as “Another Horse Creek ‘Shooting Match’” and, in a Chicago newspaper, “They Quarreled Over Hogs.” People from Horse Creek were also often made fun of for their backward ways, being called “Barefoots” and “Horse Creekers” in local newspapers.

The Reeves brothers, or Clark brothers as they called themselves, were perfect fits, and it looked as if they had finally slipped away from their violent past and found a place where they could grow old.

One thing was not going well for the brothers—the peddling business. The enterprise would have been tough in most places, but Horse Creekers were not wealthy, and the area had a small population. This forced the Reeves boys back into a bad habit. They began traveling periodically to Ohio by train and robbing small stores to replenish their stock back in Illinois.

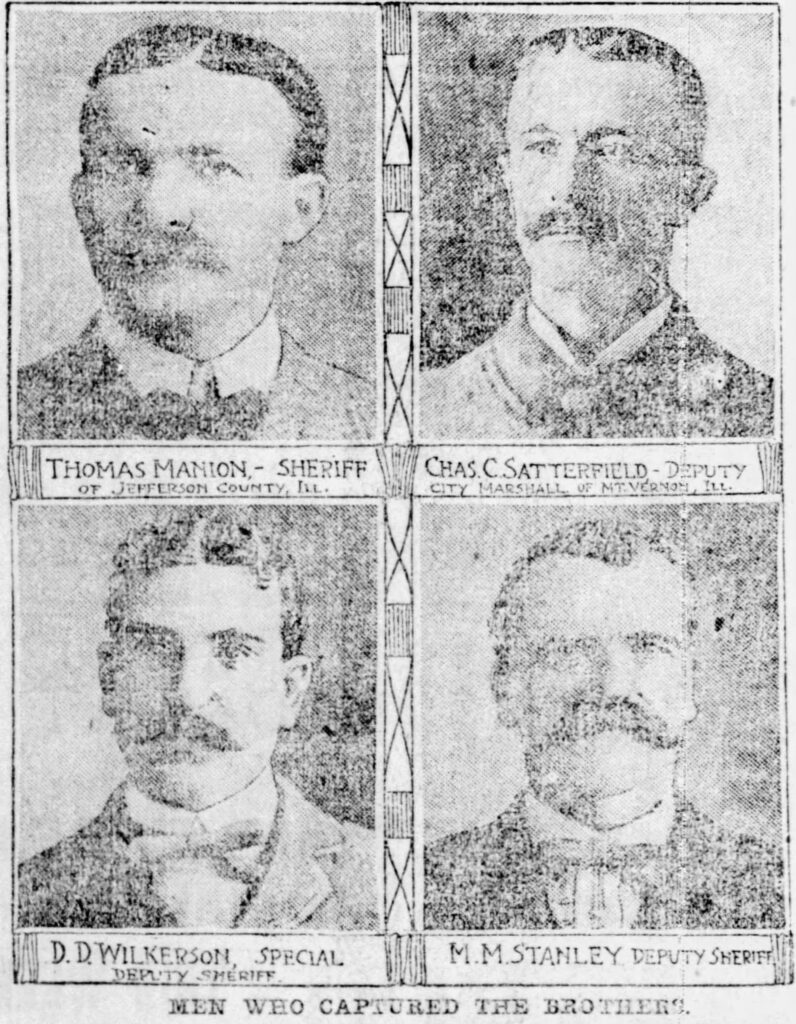

In late 1900, rumors began to spread that the Clark brothers were selling stolen goods, a story catching the attention of Jefferson County Sheriff Tom Manion. At first, Manion hesitated to investigate the matter, the two Clark men being “held in high esteem.” He also did not want to anger the rough and tumble Horse Creek community “by arresting them upon a charge of which they might show themselves to be innocent.” Finally, his instincts won out, and he began seeking information from law enforcement in the region about anyone matching the description of the Clark brothers. A response came from Kentucky telling him all about the Reeves brothers, and Sheriff Manion was warned to take extraordinary measures when trying to arrest them. The sheriff did so, putting together a four-man team of seasoned lawmen.

John Reeves went quietly enough and was taken by buggy to where his brother, George, resided with the William Byars family on the banks of Horse Creek. Once there, one officer held John down at gunpoint while the other three went to make the arrest. As the three men walked cautiously forward, John told his captor, “Just watch the hill up there and you’ll see a matinee. There will be three dead men up there in a minute and George won’t be one of them.”

As the three lawmen approached the Byars home, they saw George Clark playing in the yard with the Byars children. When George saw the three men approaching, he instantly “attempted to draw his revolver but his thumb caught in the flap of his coat. Seeing the odds were against him, he gave up.”

John Reeves was shocked when he saw his brother being dragged back in cuffs by the sheriff. “He sank back wearily and said to the man holding him down, ‘“Well I’ll be damned,”’ to which Sheriff Manion replied, “You’ll be dead if you move!”

The news of the arrest made newspapers across the nation. The Grand Falls Montana Tribune and the Knoxville Tennessee Sentinel, for example, carried lengthy articles about the sensational event, and the St. Louis Globe Democrat, in a full front-page article called the arrest “the most important one ever made in this county” and “under circumstances of the most thrilling nature. Their apprehension has won undying fame for those who rounded them up.”

The next day after the arrest, Horse Creek farmers came in droves to the Jefferson County courthouse in Mt. Vernon, offering “to furnish bond for any amount.” Then news came from Frankfort, Kentucky, clearly identifying the arrested pair as the murderous Reeves brothers. They were soon placed on a train, and under heavy guard, sent back to Indiana to stand trial.

Their outlaw adventures, however, had one more dramatic act.

On their way from the train station at Huntingburg to Jasper to stand trial for the 1885 murder of the two sheriff’s deputies, George Reeves made an attempt to escape from the buggy in which he and his brother were being transported. As Reeves began scaling up a bank, deputy Peter Huther caught up, grabbing at the fleeing man’s legs, only to discover the criminal had removed one of his handcuffs. The hulking Reeves used them now to try and beat Huther to death, viciously swinging the half-freed cuff like a deadly club. As the deputy desperately dodged blows, he barely managed to lift his pistol and fired a bullet into Reeves’ chest. Even then, the powerful bandit wrestled Huther down to the ground. Finally, the deputy beat his assailant back with the pistol and Reeves fell, dead.

Newspapers from all over the state and the nation followed the story of the attempted escape and death of George Reeves, along with the ensuing trial of John Reeves. Sheriff Manion of Jefferson County, Illinois, made sure he had a front row seat at the trial. Meanwhile, George Reeves’ body was buried without ceremony in the Jasper cemetery, not far from the grave of Deputy John Gardner, one of the men Reeves had murdered sixteen years before, further adding to the melodrama.

The verdict against John Reeves, while called a compromise on the part of the jury by one Jasper paper, was a shocker. Perhaps enough time had passed that no one carried the initial passion for justice and revenge. Maybe too, the aged John Reeves made such a sad and forlorn looking spectacle in the court room, it swayed the jury. At any rate, Reeves was sentenced from two to twenty years for manslaughter.

There was one public voice of complaint regarding the relatively light sentence. The Jasper Weekly Courier believed the convicted man would probably only serve two years of that time and suggested “A quick, judicious hanging might even up matters.” Reeves, in fact, served only one year and one month before being released for good behavior and bad health. This research found no other records of what happened after his release, John Reeves simply disappearing into the dark waters of time.

*********

The Reeves gang never received the recognition of groups like the Jesse James or Dalton gangs in the border region of the country, but they did manage to escape the wholesale lynching that fell upon the Reno and Archer gangs who also terrorized the same general area of southern Indiana. And though the Reeves gang never achieved the level of a “social bandit” group, one supported by local citizens, they did evolve beyond petty crimes in Indiana. Moving on to Kentucky, they become a sophisticated and far-reaching group of safe robbers. After escaping prison in Kentucky, they sought to escape their bandit life in the Horse Creek region of southern Illinois, but to no avail. Over the years, newspaper stories about George and John Reeves were of great interest to the public, especially as the turn of the 19th century approached, and their surprise arrest in Horse Creek in 1901 brought back the memories of the so-called Jesse James types of desperadoes to a nation just beginning to idealize the days of the American frontier. Thanks to the abundance of newspaper reports, their story, lost to time until this study, adds rich narrative to the literature of criminal activity in the lower Midwest in the post-Civil War era.