The important teachers in my life were not only in school, they were everywhere. Some of their essential teachings, however, were so subtle and of such a short duration that I have remained mostly unaware of of the gifts they bestowed on me. One such teacher, however, recently came back into my memory.

In gathering material for my book, An Almost Perfect Season: A Father and Son and a Golden Age of Small-Town High School Basketball, I became aware of how many amazing Bluford Trojan basketball players were so quickly forgotten, especially if they played on a team that lacked a good season. Merle McRaven, who graduated from Bluford in 1962, was one such Trojan athlete. Interestingly, his life and mine would briefly intersect, his kind actions having a profound effect on my life, a story I tell in part in an Almost Perfect Season, and one I will share now.

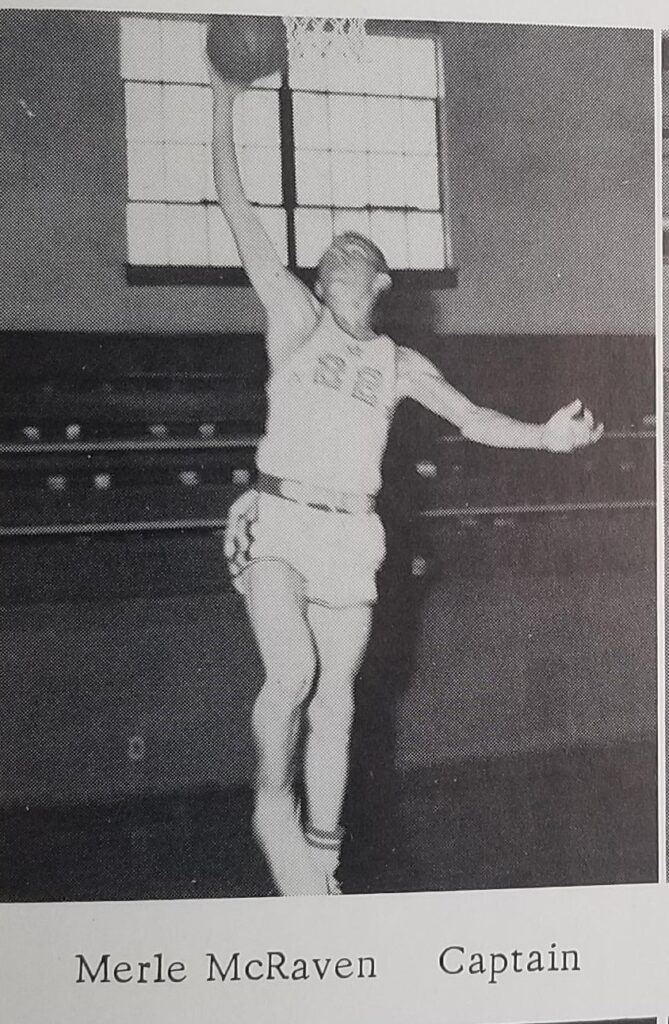

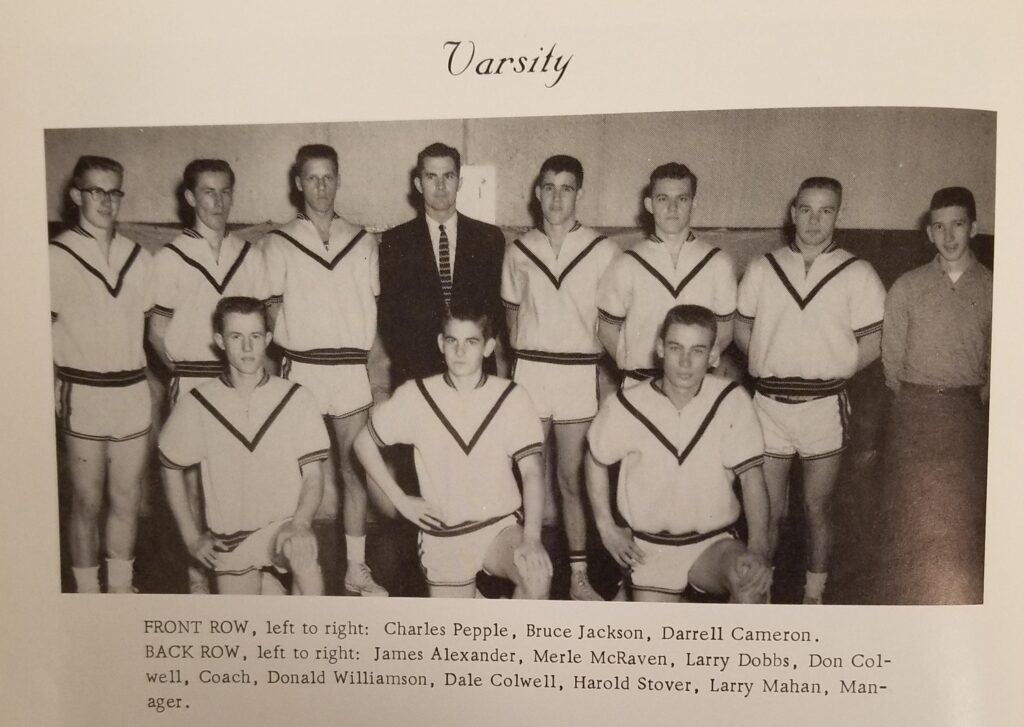

Early 1960s newspaper articles reveal that Merle McRaven was a high scoring player in high school during his senior year. McRaven was also recognized as a nifty playmaker for the Trojans. The team itself, however, had only an 8-12 record that year, even though they pulled two upsets against very strong teams.

McRaven was the team’s captain and leading scorer, tallying an average of twenty points a game. McRaven was also among the top scorers in the Little Egyptian Conference and was a dead eye at the foul line, shooting ninety percent from the line his senior year.

Merle was apparently popular off court too, being chosen by his classmates as the prom king his senior year, with lovely Veronica Clark as the queen.

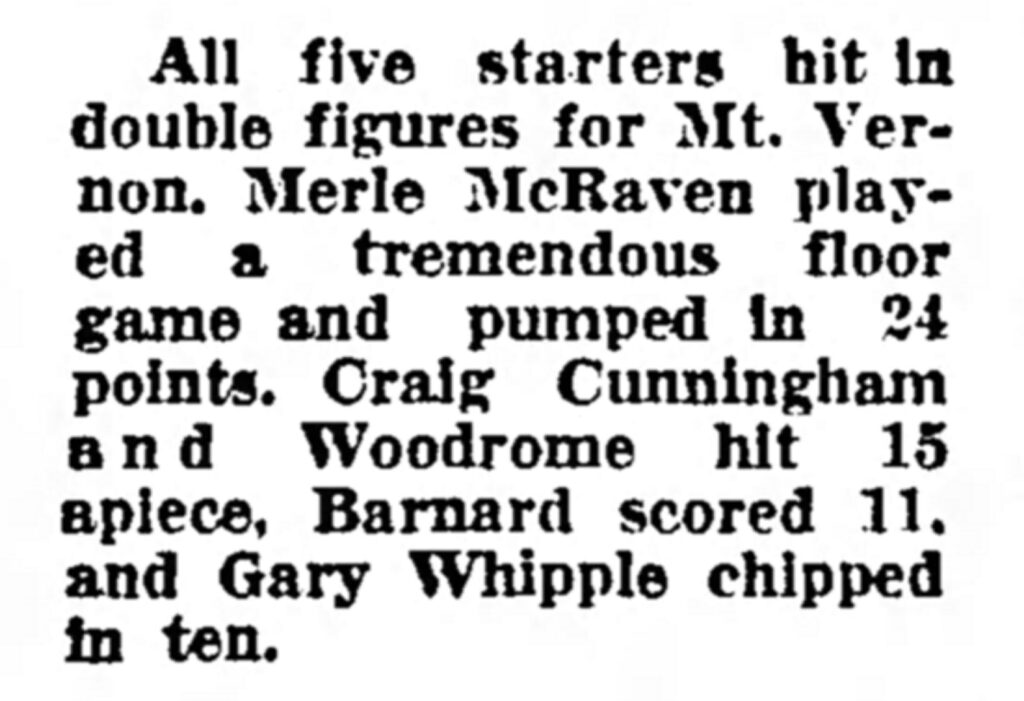

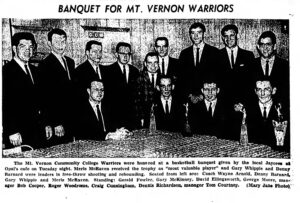

High school graduation did not stop Merle from getting more sports acclaim. He enrolled at Mt. Vernon Community College where he blossomed even more as a player, instantly making a mark on the Warrior basketball team as both an amazing “play-maker” and prolific scorer. For many years he owned the team’s free-throw accuracy record.

Merle was chosen as the team’s most valuable player in 1964, in his final year of playing for the Warriors, but that was not his most important accomplishment while playing at the college. The community college in Mt. Vernon was a fairly new school when McRaven entered in the fall of 1962, and my high school coach, Roger Yates, remembers how one of the young men who hoped to play basketball there and went out for the team was very much lacking in skills. “McRaven went out of his way to try to teach the young man how to shoot a jump shot and how to move on the court. He was very patient in doing so.”

McRaven’s lessons must have helped, as the novice player made the team.

All of which brings me to how Merle McRaven came to impact my life.

As a student at tiny Farrington grade school, I felt that my chances of ever making the team at Bluford High School were slim to none. Yet, I secretly dreamed that this might someday happen. During my seventh-grade year in 1963-1964, there were enough eighth graders ahead of me to keep me from even dressing for the Farrington A team games. At that time, I also struggled with feelings of not fitting into the male farming culture of my community, as I was not mechanically inclined like my brother, nor cared much about driving tractors. I had hoped, however, that I might at least excel in basketball, as playing well on a grade school team, and especially on a high school team carried high status even among the farmers.

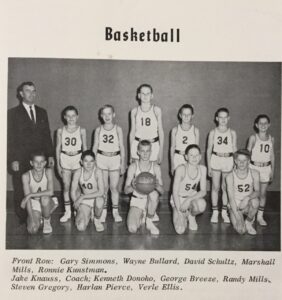

My eighth-grade year was somewhat better. After a growth spurt, I was finally playing on the first team. My budding height had other ramifications. My arms were so long, I could keep getting a rebound under the basket and put it up again and again until it went in. I racked up large point totals in games doing this, often scoring more points than my other teammates combined. But my shooting form was ugly and ungainly. Our coach, David Stewart, tired of watching me throw an offensive rebound time after time toward the basket until it finally fell through, worked with me in the evenings after school on some pivot moves under the basket, but to little avail. Worse, even with my awkward scoring, the Farrington Eagles won but a single game that year, and my hopes of playing in high school seemed as remote as ever.

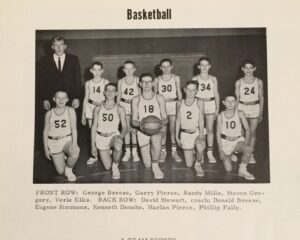

It did lift my hopes some that my older cousin, Gary Wayne Pierce, a Farrington boy, played varsity as a senior that year for the Bluford team and that he was their leading scorer. Uncle Red began taking me to some of my cousin’s games, and from him I learned the basics about Bluford basketball culture, a culture I secretly hoped to join someday: Bluford played in the eight-school Little Egyptian Conference; Waltonville and Wayne City were our main rivals; we played in the best small-school holiday Christmas tournament in southern Illinois but had yet to win a championship; we had not won a conference regular season championship, a conference tournament championship, or a district championship since 1955; and we were lucky to win half our games during the regular season.

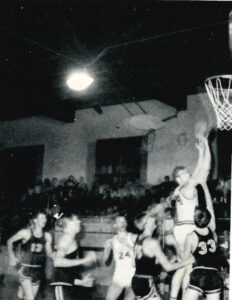

Watching the high school games, I thought the Bluford varsity guys were gods. Gary Wayne was a natural shooter with a perfect-looking jump shot. He had several games where he lit up the basket, playing with great intensity, and I was elated when I watched him score a long bomb in the game against Mills Prairie, a last-second shot that won the Bluford High School homecoming game. For many weeks after that, I secretly fantasized about pulling off such a feat.

Seeing Bluford High School play gave me a whole new set of heroes to look up to and aspire to be like. But I just could not imagine I would ever be good enough to play at that level on a Bluford team.

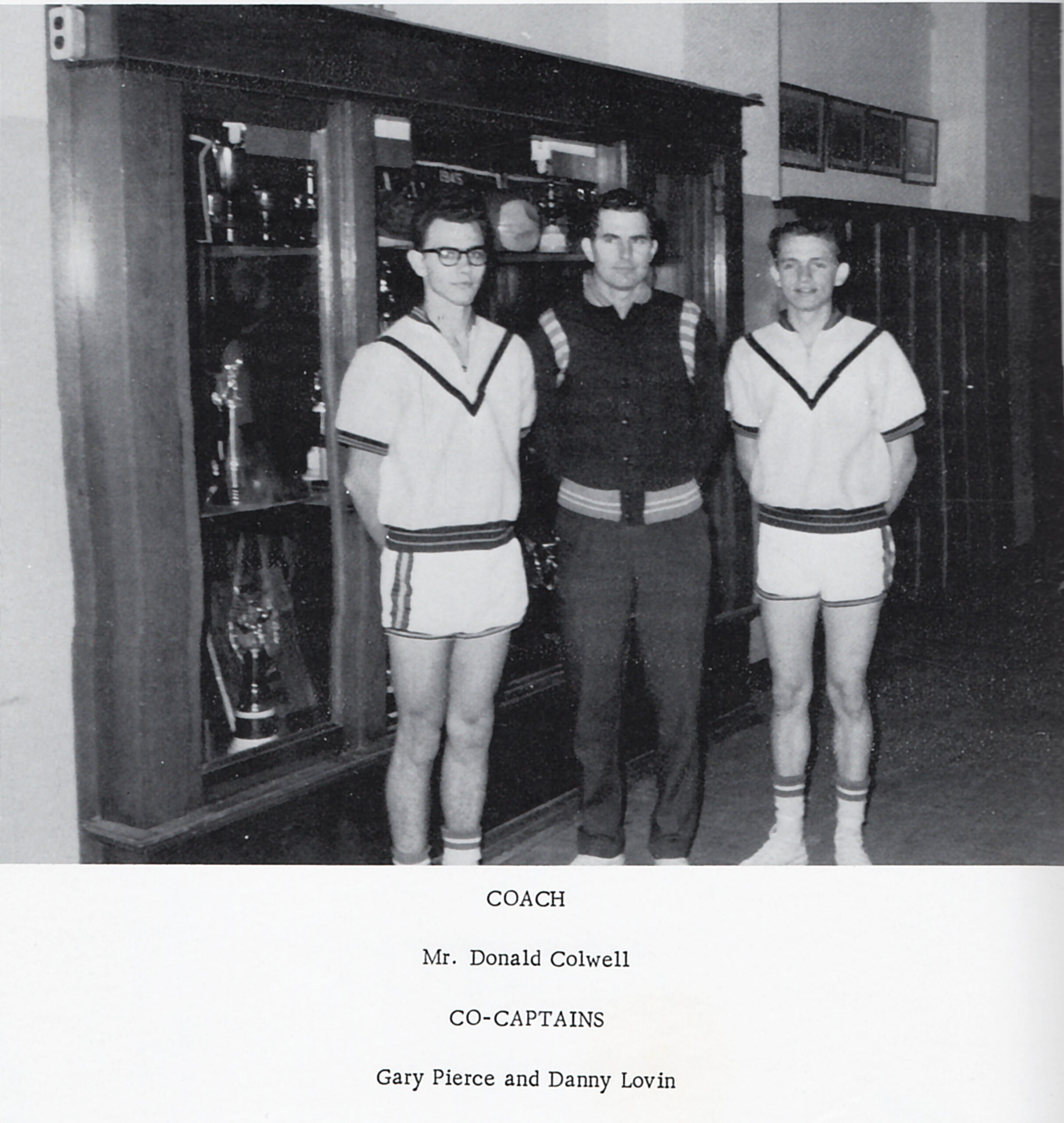

I also became familiar with the Bluford High School basketball culture during my eighth-grade year by going to see my older brother, Marshall, who was a freshman, at his basketball practices. Bluford High School was so small, it did not have a freshman basketball team, so freshmen were thrown up against sophomores and even a few juniors when trying to make the junior varsity squad. The Bluford head coach, Don Colwell, had no assistant coaches either, so he worked with both teams. Marshall, like the other freshmen, rode the junior varsity bench most of the time.

One bleak winter evening, I came in with Dad toward the end of one of Marshall’s basketball practices. If either of the two of us looked like an athlete, it was Marshall. He was almost as tall as me and slender—handsome, really—clothes always fitting him perfectly. I was tall and stocky, not fat, just big, with my shirttail forever working its way out of the back of my pants no matter how tightly I cinched my belt.

When Dad and I entered the gym, I took a seat and prepared to be bored, but that soon changed. Coach Colwell, a tall, ramrod-straight man with curly dark hair, motioned my father to the gym floor while I stayed up in the worn wooden bleachers, watching Marshall and the other glum-looking freshmen, their pale legs churning as they ran “killer” sprint drills. As they talked, both Dad and the coach turned often to look my way.

Across the gym from where I sat, on the wall above the bleachers, was painted the large profile of a man’s head. He wore an ancient-looking helmet with the words Bluford Trojans written beneath in deep blue lettering. I was contemplating why anyone would choose a Trojan warrior as a mascot—after all, they were the losers in the Trojan War—when my dad came back up to sit beside me, his face lit with animation.

“They must like tragedies,” I said, and pointed at the mascot.

My dad looked at me like I was an idiot. “Go down and talk to the coach,” he said.

I walked self-consciously to where Coach Colwell stood with a whistle dangling from his mouth. He looked at the players on the floor and not at me as he talked.

“What size shoe do you wear?” he asked.

The question puzzled me. “Thirteen,” I answered.

“You’re six feet tall?”

I looked down at the floor and then over at the practicing players and my brother. “I think so. I don’t really know.”

The coach sent a player running to get a tape measure, but instead of measuring my height, two sweaty players, glad for the break, measured my arm span from fingertip to fingertip. By then, the entire team had drifted over, including my brother, who looked miffed.

My father lumbered down from the bleachers, picking up his pace when he came across the floor.

I felt like an awkward ugly bird, standing there with my arms outstretched, the weight of my held-out arms starting to cause them to quiver.

The coach looked at the tape, a smile growing on his face. He turned to my dad and said, “A person’s height will usually be the same as their arm span, but the arms sometimes grow to their full length before the final height is reached. The measurement shows your son will be at least six and a half feet tall, maybe taller.”

As it would turn out, I just had really long arms. Still, the possibility of my potential growth paid dividends. The coach asked my father to bring me to the next practice.

The next afternoon, my dad picked me up at Farrington grade school and took me back to the Bluford High School practice. Coach Colwell had a short, unassuming-looking young man standing next to him, easily bounding a basketball in perfect rhythm back and forth between his huge hands. Dad paid more attention to the stranger than I did.

“That’s Merle McRaven,” Dad said as we climbed into the bleachers. “He played for Bluford a couple of years ago. A great shooter.”

Dad and I had just sat down on the hard wooden bleachers, me with an unopened book in hand, when the coach saw us and motioned to me to come down to the floor. Dad nodded, but I paused, unsure of what might be expected of me.

I had long ago learned to read my dad’s expressions. Around our house, it was an important tool of survival. When I hesitated, his expression said, Get your ass on down there, so I hustled to the gym floor.

Coach Colwell said to me, “This is Merle McRaven. He’s going to work with you on a jump shot and some other moves.”

McRaven shook my hand and led me to the top of the foul line. The rest of the junior varsity squad worked on a play at the other end of the court, seeming unconcerned with the stranger or me.

“Just watch,” McRaven said.

McRaven spun the ball in his hands then dribbled to his right in a leisurely manner towards the foul line. Suddenly, he took a long stride then planted his right foot before going up into the air, his shoulders square with the basket. At the top of his jump, in a smooth flipping motion, he released the ball, his right hand stretched out as if it were reaching into the basket.

The ball rotated as it climbed in a graceful arc, then, falling, it dropped through the rim perfectly, making the net dance. The entire process had been seamless.

He did these moves three more times with the same results.

“Stride, set, shoot,” he instructed as he handed me the ball.

Because I was a visual learner, McRaven’s teaching style was great for me. Soon I was imitating the moves to the point that Merle smiled and nodded.

“Let’s try some pivot moves now,” he said, and we moved closer to the basket. I noticed he had just a hint of a smile on his face.

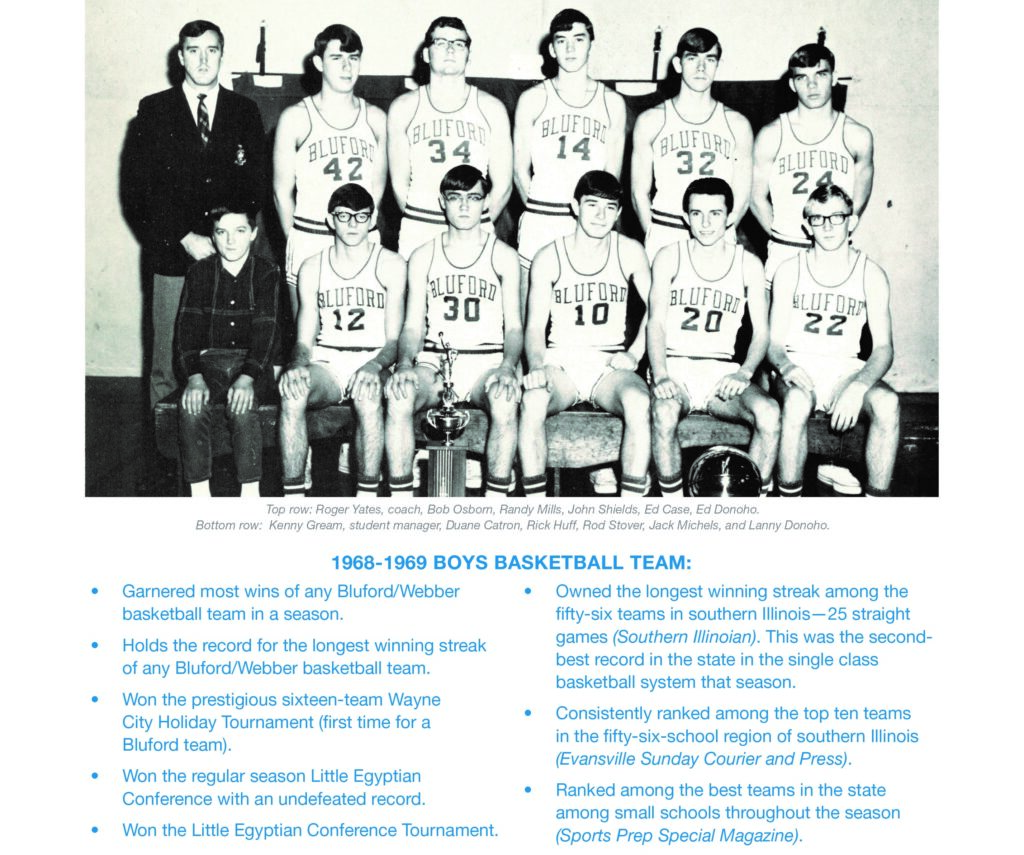

Merle McRaven worked with me several times at the Bluford gym that year, complimenting me when I did something correctly and calmly showing me what I was doing wrong and how to fix it. Merle’s gentle directions did wonders for my confidence, and his guidance on shooting a jump shot helped me to develop a skill I had been sorely lacking. By the next year as a freshman, I had improved to the point that I started on the junior varsity team and by my sophomore year, I was starting varsity. Two years later, I was privileged to start on a Bluford basketball team that would go down as one of the best Trojan teams ever.

I was never around Merle McRaven before or after the basketball practices where he worked with me on my basketball skills. Of course, everyone has their problems, and I’m sure Merle was as human as the rest of us, but at those times he worked with me, I knew he was going out of his way to help, a situation that made me feel good about myself, as I was clearly worthy of this older person’s time.

It has been almost sixty years since Merle McRaven took the time to show an awkward eighth grader how to shoot a jump shot and make a few moves to the basket. Since then, there have been many changes in my life and many changes in the world. The old Bluford High School gym is gone, fewer kids seem to go out for sports, and many of the local newspapers that use to carry amazing stories about small-town high school basketball are extinct. But some of that old world lives on in me and in all those other once hopeful high school basketball players of that era. The basic skills Merle taught me so long ago gave me confidence and esteem at a critical time in my life, intangible elements I would use to build my life with as an adult.

Sadly, Merle McRaven died in 2004 at the age of fifty-nine, a few years before I became reflective enough to realize the gift he had given me so many years before. I never had the chance to thank him. Even today, I can still image him saying, as he encouraged me along in the old high school gym, “stride, set, shoot.” I can only hope that the spirit offered in this narrative puts some good thank you vibes out there in the ether. Thank you, Merle.