They answered the call to help save the world from the two most powerful and ruthless war machines ever. —Tom Brokaw, The Greatest Generation

Perhaps shame is best responded to in the long haul, as one may have enough life experiences when they are older to better forgive oneself. Still, shame stings, especially when you cannot do much about it, or find it easier to just keep your mouth shut. Confession may help, especially when given context. This is the reason I believe that moves most writers to write, whether they realize it or not. That being said, here is some context to one of my many stories of shame.

Like sad left-over little piles of blackened melting snow in the spring, the once young soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen of my father’s WWII generation are disappearing. Sadder still, few of the succeeding generations will be able to imagine what those men and women, and their families, endured.

I was fortunate to catch real-time glimpses of that reality, however, having read through my mother’s diary many times over the years. She was a Waltonville, Illinois, high school student during the entire war, and the conflict, especially its impact on her family, was often touched upon in her narratives. Indeed, the period of my mother’s diary-keeping witnessed some of the greatest changes and most dangerous times in our nation’s history, events on which she often dutifully commented. Early on, for example, she wrote, “As I realize how many events, which history will give much space to, have happened in the last few years and how fortunate I am to be living in them, I want to always appreciate this fact. Most people will probably just take these events for granted.”

The Second World War caught much of her attention.

When Mom’s brothers went into the war in 1942, things looked their darkest. Both the Japanese and German advancements seemed unstoppable. While the war relentlessly progressed, newspapers and radio programs spoke of constant battles and fatalities. Three of her brothers– Tommy, Maxey, and Dean Newell–would serve for three long years in training and then in combat overseas with but a single home furlough before they shipped off to war. The details of one of the visits by her brother Tommy was one of the first things detailed in her diary.

At last, all our dreams about Tommy coming home came true. He slipped in last night about midnight. We were all in bed and I guess all asleep but Mom. She heard the door open and he came in and lighted the lamp. He looked just fine and seemed like ‘Old Tom.’ He only gets to stay for two more days, then he’s off to who knows where.

Besides worrying about her three brothers, who wrote letters home infrequently, Mom was also concerned about her father, James Newell, to whom she was very close. She wrote how her father “has to listen to Gabriel Heatter [a popular radio commentator during WWII] every night. He thinks he’s tops. But if the war news is bad, he will turn off the radio and just look so sad. The anxiety and tension about my brothers are just too much for him.” Early on too, she wrote, “Along with thoughts about school come constant thoughts of the war, as it has brought deaths to thousands. The war has come close to us here at home with my three brothers in the army.”

Mom’s diary entries indicated that the Newell family had hardly any idea where the three brothers were or what they might be having to endure. It did not help matters that the three brothers were men of few words, as their lack of writing home demonstrated. Uncle Tommy did write one brief note, telling he had been promoted, causing my mother to write, “We finally got a letter from Tommy yesterday and he has been made a Corporal! 2 strips now and we are proud of him!!” Her brothers Dean and Maxey also wrote infrequently, causing my mother to lament in her diary, “Dean is on his way to who knows where. Still we write to him and pray that he is o. k. We have received only two letters from him. I finally got a letter from Maxey last week and wrote to all 3 boys last night.”

Having studied their discharge papers, I know that Uncle Dean was the first to be sent overseas, serving in a mortar platoon, first in North Africa in 1942, and then in Italy. Uncle Tommy was in the infantry, going first to England, and then into France after D Day. Uncle Maxey also fought in the infantry, serving in the Pacific Theater. He ended up being a part of the fighting in the Philippines upon General MacArthur’s promised return.

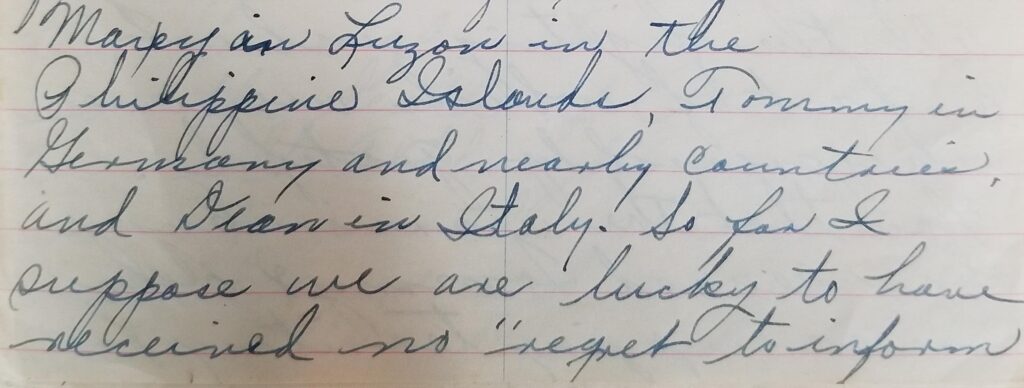

As the war drew closer to its end, more information about the Newell brothers was apparently available. In the latter part of the war, my mother wrote,

Maxey is in Luzon in the Philippine Islands, Tommy is in Germany and nearby countries, and Dean is in Italy. So far, I suppose we are lucky to have received no “We regret to inform you” telegrams except the one in Nov. 1944 when Tommy was slightly wounded in Germany. He was in the hospital for four months with that ankle injury and wasn’t there in some of the fiercest fighting, which was raging, but he went back to the front before V-E Day and got his share of it. He got the Purple Heart Medal which we are treasuring. Dean got at least 3 battle stars while fighting in the mountains in Italy. However, he came through all the fighting unhurt, a fact of which we are inexpressibly grateful.

Maxey, however, seemed to have fallen off the face of the earth. Just after the war ended in Europe in early May, Mom wrote of some happier news.

Now that the war in Europe has ceased, Tommy and Dean are occupying territory for the time being. In May, Dean had 73 points and Tommy had 66 points towards coming home. We had hoped so much that at least one of the boys might get a discharge, but I suppose we’ll just have to keep on hoping. And Maxey—well we don’t know much about him. You see we haven’t had a letter from him for two months. He has been in battle in the Philippines during this time we know, and we can just hope and trust that he is well. However, Luzon has been liberated this week and we hope he will write soon.

When the Japanese finally surrendered in early September of 1945, the Waltonville Newell clan was overjoyed. Slowly, the brothers found their way home, and in their shy fashion did not let anyone know when they were arriving. Mother captured the latter events in her diary.

On the morning of Oct. 17, 1945, I shall never forget it as long as I live—Dean came home from Italy. It was wonderful to see him after 3 years absence. I found myself speechless upon being the first of the family to see him that morning. He was just as glad to be home as we were for him. Then on Dec. 3, Tommy came home. He came in during the night and woke us up saying, “I didn’t aim to scare you, I just wanted you to know I was home.” How can I even forget how I felt that moment I recognized him? It was so good to have both Dean and Tommy at home once more. Then another surprise—Maxey came home Dec. 10th. He was down at Doug’s restaurant when Faye and I went to eat our lunch at noon. And as in Dean’s case, I was the first to see and speak with him. I saw him sitting there and at last recognized him. My first words were (how foolish) “Why Maxey, I didn’t see you.” He ate dinner with Faye and I often wonder why I didn’t have indigestion all afternoon, I was so excited. So after almost five years our family was all together again.

Enter my mother’s second born, yours truly.

************************************************

When I was younger, my family often made the long drive down to my Newell grandparents in Waltonville on Sunday afternoons, coming back in the evenings. This was before anyone used seat belts, and on the return trip home, my older brother, younger sister, and I slept in the car’s back floor wells or perched in the rear window ledge, the hum and vibration of the car lulling us into a peaceful half sleep.

My mother’s parents always sat side by side in large rocking chairs during most of our visits, Grandpa Newell’s hand occasionally pushing the back of his wife’s chair, since Grandma Newell’s feet never touched the floor; she was two inches shy of being five feet tall.

Born in the 1880s, they were already old when I first came to know them, gentle and sweet in their old age and with low energy. They told us simple stories like “The City Mouse and the Country Mouse” over and over, sweetly asking my siblings and me to comb their hair and gently scratch their heads as payback for their yarns.

Downstairs, the Newell house was a museum, the kitchen stove a wood burner, the soap they used, pine tar.

Upstairs was blocked off by a string at the stair’s bottom, a woody twine my grandmother had strung there, a few bright pieces of red cloth tied to it to add to its warning. It did not take much courage on my part to scoot under the hapless string.

It was during my first illicit visit upstairs that I discovered my three uncles’ army gear, stuffed in a closet—medals, including Uncle Tommy’s Purple Heart, along with three Good Conduct awards, assorted dusty garrison caps, wool army pants and khaki shirts, an Eisenhower jacket with ribbons, including the “ruptured duck” discharge patch, a pair of polished combat boots, even a dull but wicked-looking samurai sword. The latter was packed away in a piece of fragile silk cloth. In a shallow box were discharge papers, reporting all the details of their service.

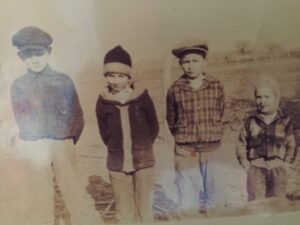

There was even a faded photo of all three brothers, gathered in front of my grandparents’ house just before they all left for their initial training. Tommy and Maxey stood as straight and slim as sticks, as they would be even in old age, both possessing a large New England Yankee nose common among many Newell family members, including myself. They were as somber looking as two sphinxes. Uncle Dean was smiling and already showing signs of plumpness.

When they finally returned to Waltonville in 1945, all safe and sound, Mother wrote, “It is the happiest day of my life.” I never heard my uncles talk of their experiences in the war, but I can easily imagine how each Newell boy felt as he placed his army gear away, folded and then stacked in a familiar room in the house where he had grown up, overjoyed to be shed of it all: the boredom, the bad food, the dangers of combat, the scenes of war’s unspeakable destruction, all of it to be forgotten until I stumbled upon this treasure and pillaged it like an ancient Hun.

******************************************

I was eight when I first stumbled upon my uncles’ army stuff, and the rest of that winter, I would sneak upstairs almost as soon as we would arrive at the house in Waltonville. I would steal into the unheated room, my breath often visible in the cold dry air, and rummage through the closet, hyper-conscious of the sound level of voices in the rooms below. When they stopped talking, I would hold completely still until the voices started up again.

By that summer, I was marching right up into the upstairs room’s stifling knock-you-down heat, pulling out the treasures right and left from the closet and placing them on a sagging bed before kneeling and assessing each item, pawing and turning them over again and again, as if the pieces were ancient talismans. All the while, sweat streamed down my face. The spell was broken only when someone would holler from downstairs that it was time to go.

At first, I took only the small items—the caps and some of the medals—stuffed them into my pockets, and hid them in the back of my closet, in a grocery sack, once I got home. I played in the Eisenhower jacket at my grandparents’ for several Sundays, paraded in the outfit in front of everyone downstairs, making my grandparents laugh, until I worked up the courage to ask to take it home to play in.

I jumped up in the air when Grandma Newell said yes.

The rest of the stuff, except for the boots, I took home shortly after that, no one apparently noticing. Or, not caring.

I didn’t even ask to have Uncle Tommy’s combat boots when I discovered them that second time, just wore them home. I was eleven by then, and the boots, although the high-topped, laced-up kind and quite grand looking, pinched my feet and left blisters if I wore them too long. But wear them I did. With the boots, I could put together a fairly complete army outfit with all the other stuff I’d taken from my grandparents and wear them to play soldier.

There was a price for authenticity. Along with the blisters, I also sweated gallons of water in the sultry summer heat while wearing the wool Eisenhower jacket and moth-eaten army pants.

Armored in the many eclectic pieces of my uncles’ army uniforms, I found that the rural landscape of my youth offered a multitude of terrains in which to play war: thick woods, grassy fields, and steep hills, all begging to be charged upon. But in my pretend world of war, I was always behind enemy lines. I played soldier alone, my older brother interested only in pretending to be a big game hunter or a farmer and our little sister being a girl.

From 1940s and 1950s war movies I watched on our television, I gleaned a complex, howbeit imprecise sense of World War II and, to a lesser degree, the Korean War. But these movies gave me enough context to construct a world of right versus wrong, fighting out this iconic theme in endless, monumental battles in our barn, in empty fields, and in the nearby woods.

Secretly, I enjoyed this solitary time, walking through the woods and fields, dodging German, Japanese, North Korean, and Chinese soldiers, the latter always attacking in “hordes,” thinking my own secret thoughts. Like any youth who played soldier, it was a romantic, innocent endeavor, save for one almost tragic event.

********************************************************

Pretending our house was a German defensive position one Saturday summer afternoon and dressed in my usual army getup, I quietly approached the front of our house, moving a few steps, stopping, and then taking a few steps again. My little brother, Marty, clad only in a cloth diaper, played on his knees with some toys on the front steps, his head bent down as he did so. I carried a foot-long stick in my belt, pretending it was a dagger, having sharpened one end with a paring knife from Mom’s kitchen.

As I silently emerged from the ditch that separated the road from our house, I pulled out the stick and threw it in the general direction of the house, imagining I was dispatching a German sentry.

Marty must have heard me moving. He lifted his head just as one end of the stick went into his eye. The scream that followed was hair-raising.

I knew Marty would quickly be attended to, and knowing my dad’s explosive temper, I ran deep into the woods.

I trotted numbly along the path my siblings and I had made through our woods, popped out the other side, and then shot across the road to where a half-fallen barn stood, hidden in the landscape of wooly brush.

One part of the barn still had a roof over it and was dry year-round, its far dark corners occupied by groundhog holes. I entered the feral room, knelt there on the dirt floor, and prayed that I had not put my brother’s eye out, even offering to put out my own eye if his eye was spared.

Three hours later, hungry, and ready to face my punishment, I slowly walked home. At some point in the decrepit barn, I had given up the idea putting out my own eye. Poor Marty would have to fend for his own like the rest of us.

The stick had just missed the eye, penetrating above Marty’s eyelid. A small scar was the only permanent damage. Dad told me gruffly to be careful, and Mom patted my head while she shook hers, knowing the whole ordeal had been hard on me too.

The episode did not slow me down one bit from playing soldier.

I did not understand how ironic my pastime was, given that my play was carried out during the accelerated ascent of the war in Vietnam. But my emphasis was on history rather than the present. In the winter, my uncle Tommy’s greatcoat, a garment that had kept him warm in France and Germany, now kept me toasty in the snow-covered fields north of our house as I imagined escaping from the Chinese at the Chosin Reservoir. In the summer, I fought off charging Nazis in the woods behind our barn, clad, incongruously, in Uncle Maxey’s tropical gear and Uncle Tommy’s wool army jacket.

At the age of twelve, I reached a high point in my pretending to be a solider. I made enemy flags out of my little brother’s, Marty’s, diapers, placing a big red ball in the center made from red dye for a Japanese flag or drawing in a big fat German swastika with a black marker for a Nazi flag. I fixed these flags to eight-foot-long chicken roost poles from our old empty chicken house and stuck them wherever I wanted to pretend the enemy camp was. Then I would sneak up through the bushes to spy or charge the enemy lines directly.

Mom must have surely thought her second born son had gone crazy, as I added the noises of gunfire, explosions, and men yelling and screaming in made up Japanese and German words. The latter was shaped from watching old WWII movies on television. To top it all off, I jumped, flopped, and rolled around all over the place, screaming out my own orders and encouragement to my men.

I was like a crazy one-man-orchestra trying to play Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue.

The end of my playing war came abruptly when I was thirteen. That late spring, I had worked on my first hay-hauling job. Afterward, a few days later, I tried to go back to playing soldier, but in the middle of a desperate battle between my heavily outnumbered platoon and a company of cruel SS troops, I heard the backfire pop of a Farmall tractor’s muffler as it swept down the nearby road, hurrying to the field.

I sneaked back to the house and threw off the sweat-soaked Eisenhower jacket I was wearing, telling myself it had grown too small for me.

************************************************

Over time, all those wonderful army things were lost—medals and ribbons likely picked off by bushes and low-hanging tree limbs as I charged for the thousandth time through the underbrush of our little woods. Other stuff was thrown away, or somehow discarded by my mother, who carried out occasional fits of extreme housecleaning. I’m sure the clothes were pretty much tattered by then, and the garrison caps, if still hanging together, of no apparent value in her eyes.

The last thing I remember seeing, just before I departed for college in Indiana in the fall of 1969, was Uncle Tommy’s now deeply scuffed and broken-down combat boots, loyal footwear that had gotten him through war and back home again, and me through several imaginary battles, now cast into a pile with other rubbish in one corner of our old smokehouse.

I had completely forgotten about the army stuff, memorabilia now if it had still existed, until a few years ago, at a reunion of my mother’s family, several years after Mom’s parents had passed away. The siblings were sitting around in lawn chairs, their low talk the soft chatter of old folks talking about a long ago past. That is, until I heard Uncle Tommy ask in the hubbub of many conversations, his voice just a weak whisper by then, if anyone knew whatever happened to all his World War II mementos.

No one answered.