So many fascinating southern Illinois high school basketball stories have been lost in the dark shadows of time. Exploring old newspapers, however, will sometimes reveal an interesting lost tale, a small gem that possesses a ring of archetypal truth, offering entertaining information and life lessons that speak to us even today. I believe this is one such story.

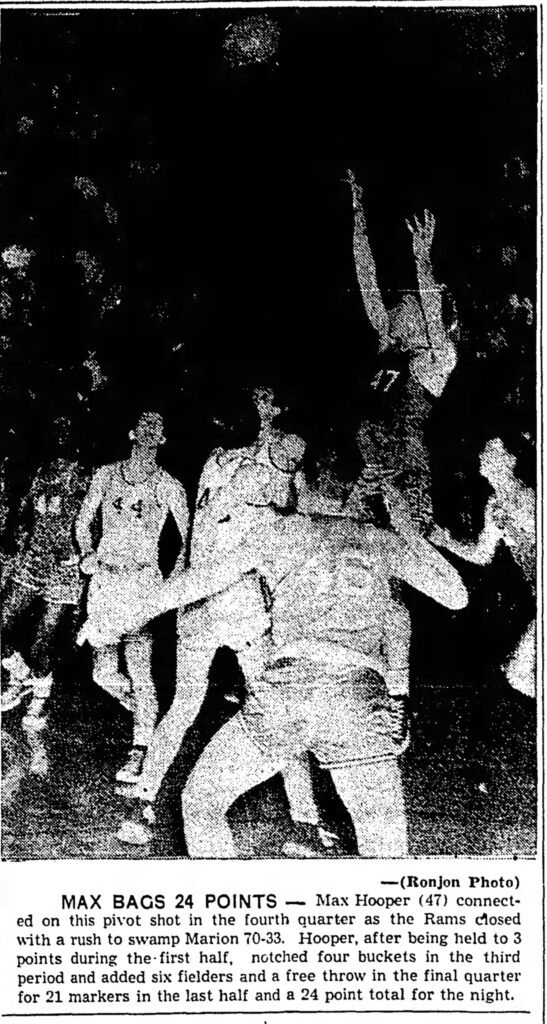

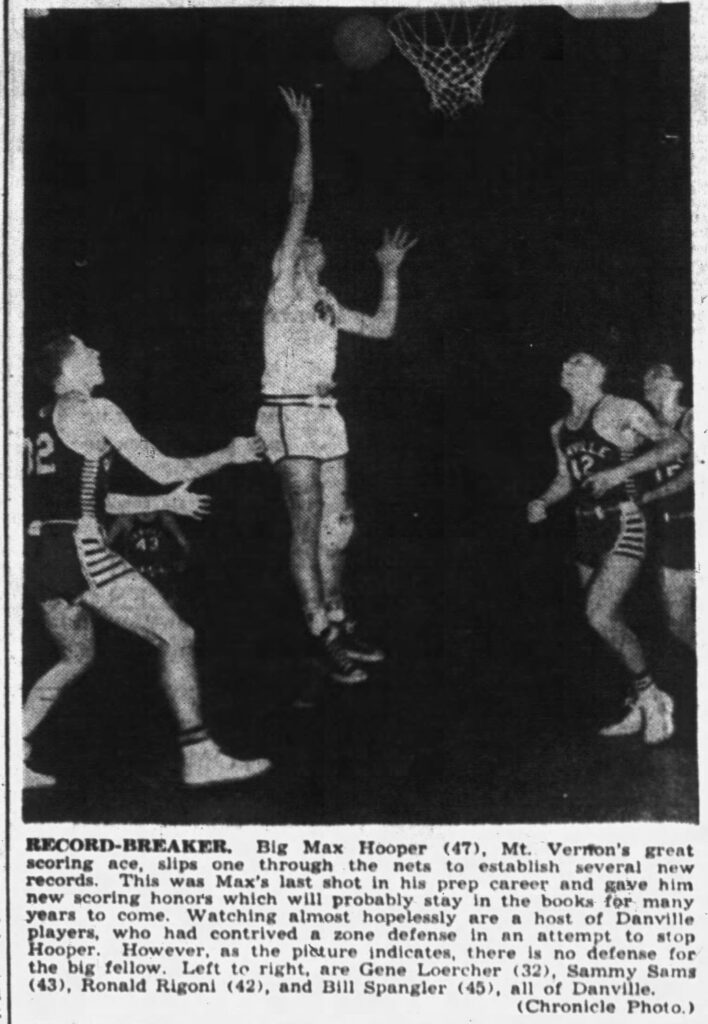

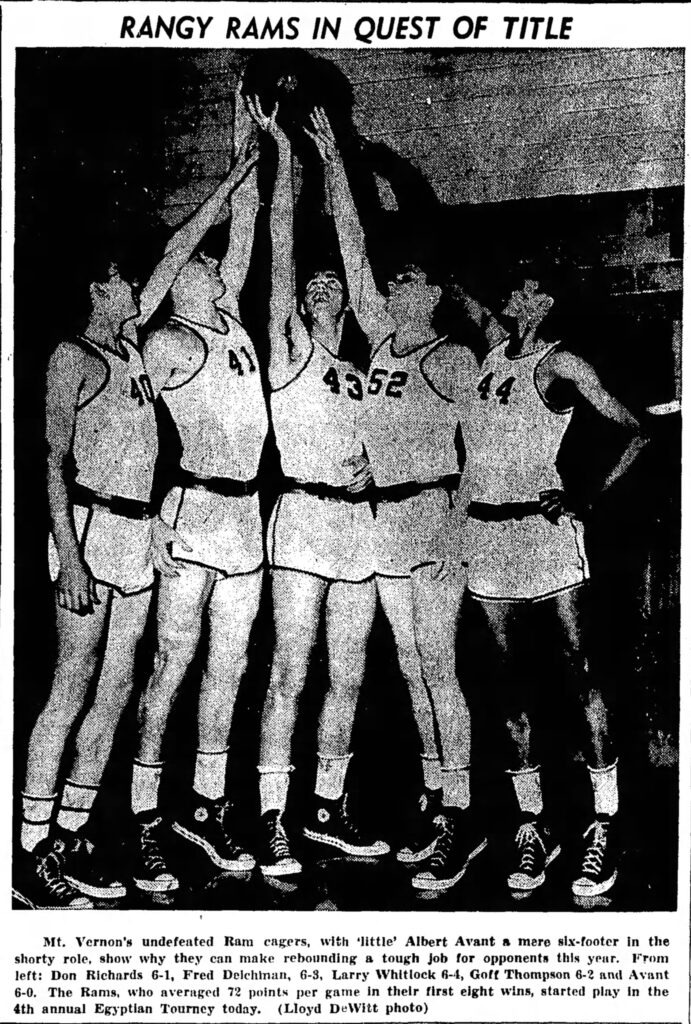

Anyone who had ever gone out for a high school basketball team in southern Illinois in the era from the 1950s to the early 1970s understood the role that height had in getting one playing time. A few extra inches could compensate for any number of weaknesses in skill areas. Back in the 1950s, a 6-4 or 6-5 high school player would have been an exceptionally tall man on most Illinois high school squads. Mt. Vernon’s 6-5 center, Max Hooper, instantly comes to mind. Hooper was the hero of the state champion Rams squad in 1949 and 1950. He was said by many Illinois sportswriters at the time to be the greatest Illinois high school basketball player of that day.

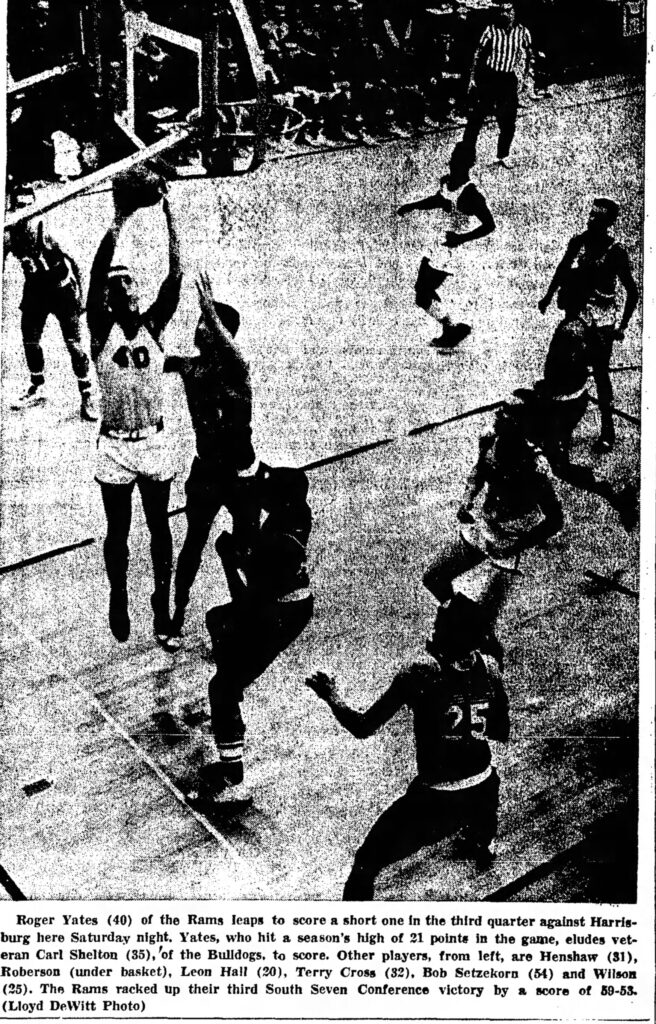

Most centers of that era, especially in small-town schools, ran in the range of six feet to six foot two. These “taller” players almost always had “their backs to the baskets” when their teams were on offense, with the guards and forwards making most of the action happen. Roger Yates, a 6-2 center for the Mt. Vernon Rams in the early 1960s, remembered, “Centers were just expected to score underneath, rebound, play tough defense, get the tip at the beginning of each quarter. A coach didn’t spend much time with a center on developing offensive moves, maybe showing him a pivot move under the basket. I was lucky having Harold Hutchins at Mt. Vernon as a coach my freshman year. He went out of his way to show me several things I could do on offense.”

Yates, at 6-2.

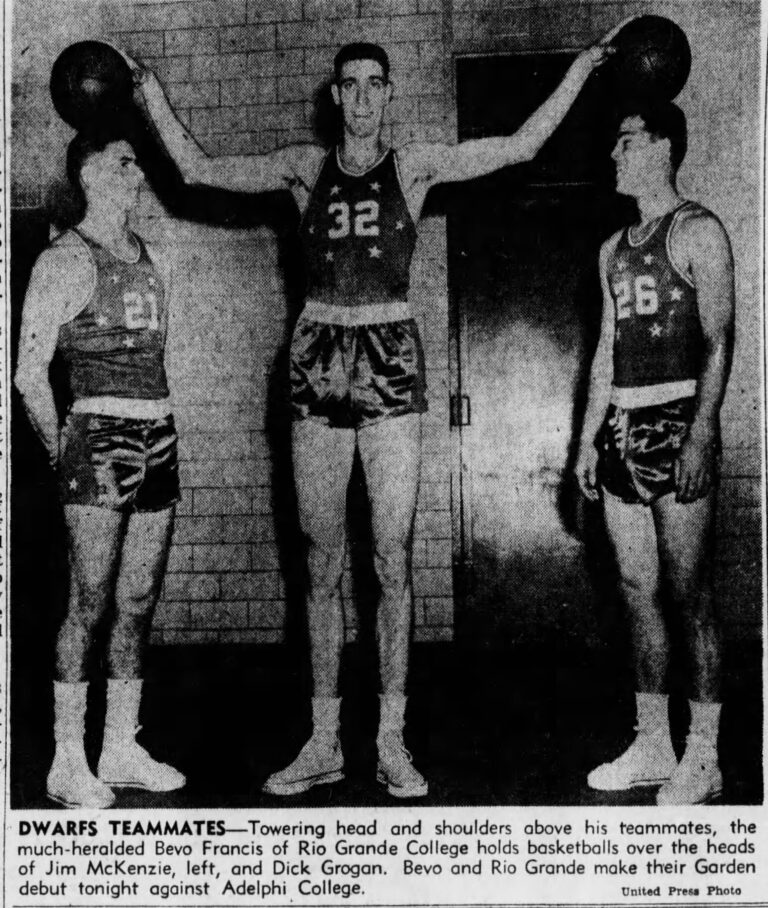

Perhaps it was Bevo Francis of small-college Rio Grande in southern Ohio who began to change basketball fans’ expectations of what a center could do when it came to offense. Starting in 1952, and on through the next season, Bevo, who stood at 6-10, erased every national college single-game and yearly scoring record, hitting over one hundred points on two occasions. One amazing skill that he possessed was the ability to make regular shots from around the foul line and beyond with a soft jump shot that had “a feathery touch.” One opposing coach noted that Bevo was “freakishly tall and had unusually long arms and a soft jump shot he could hit from twenty feet from the basket. He rarely missed a foul shot. He was the best shot I’ve ever seen.” With his skills, Bevo was able to “face the basket” like a guard or a forward, a kind of pre-Larry Bird player.

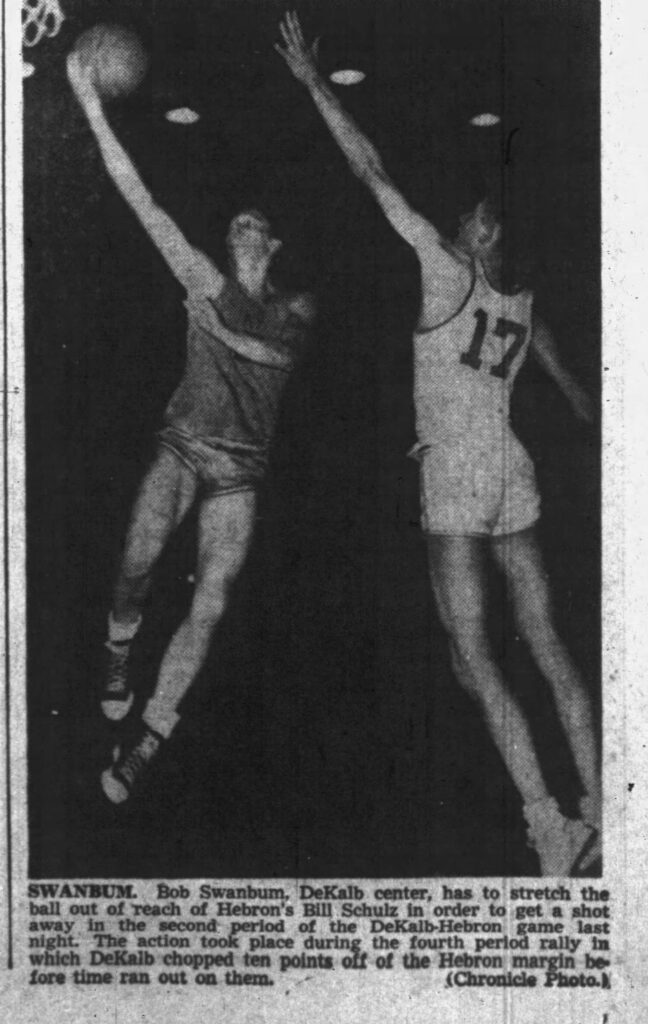

High school basketball fans in Illinois in the very early 50s had also seen other instances of what height with agility could achieve. In 1952, Hebron, a tiny school in the far north part of the state, a school with less than 100 students, would become the only team to emerge from small-school district tournament play and win a state championship in the single class system. Hebron had a giant in Bill Schulz, who different sportswriters clocked as being from six-ten and a half to seven foot tall. (It was not unusual for different heights to be given for a player by sportswriters. These ranges usually ran from an inch to an inch and a half in difference.)

Around the time giant Bill Schulz and little Hebron were making Illinois high school basketball history, another giant, this one from southern Illinois, was about to appear on the scene. He would disappear from memory, however, almost as soon as he had arrived.

________________________________________

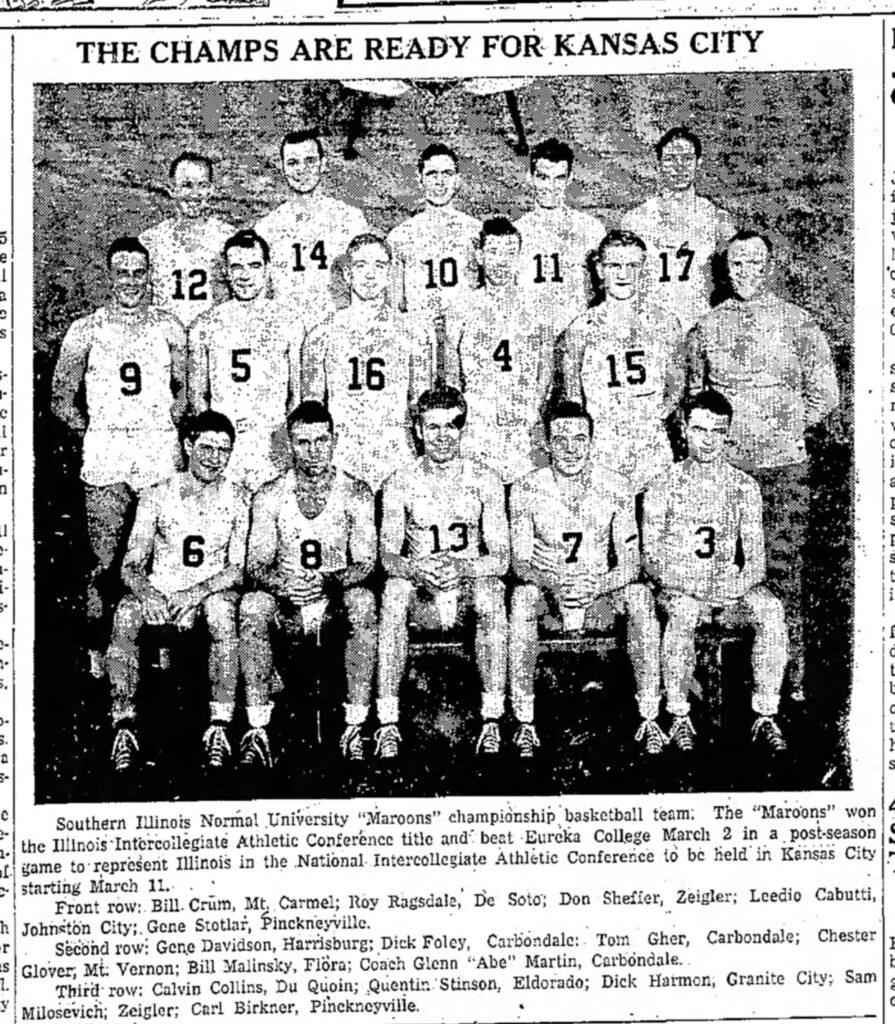

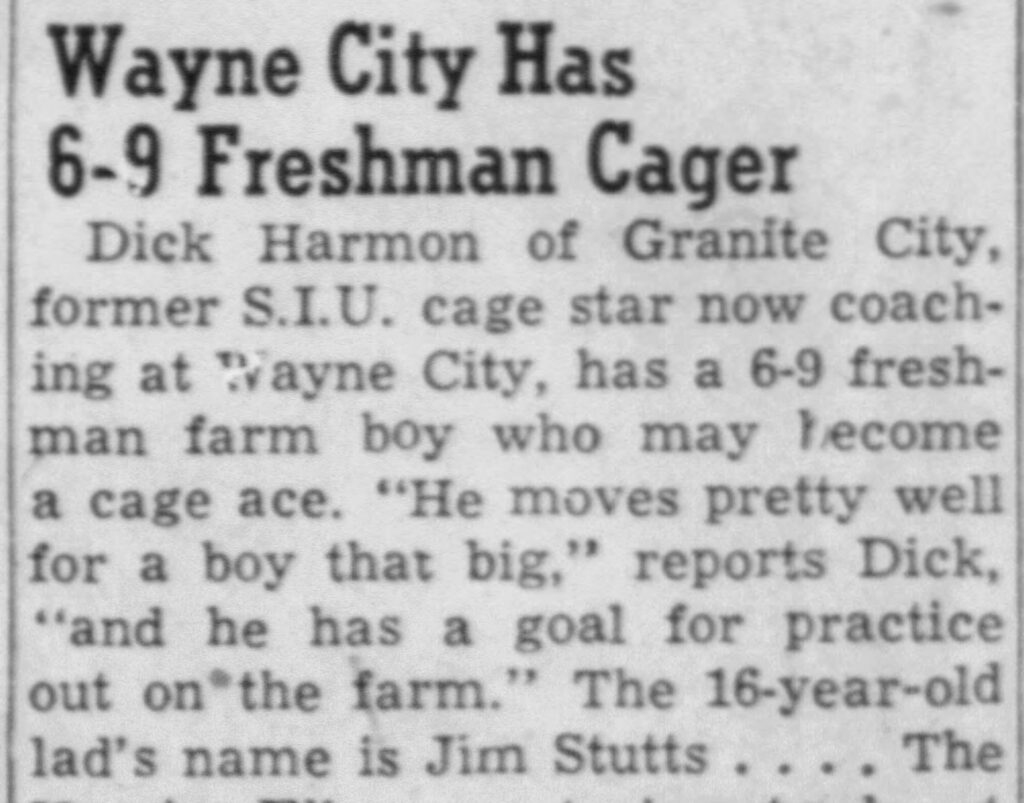

In the early 1950s Wayne City, located in a rural area of southern Illinois, was a place where raising corn and soybeans was the number one occupation. Kids who went out for basketball there likely had to work their way around farm chores when it came time to practice. The basketball coach, Dick Harmon, had taken the head coach job there in the fall of 1947, after a fruitful basketball career at Granite City, Illinois, high school and at Southern Illinois University. At SIU, Harmon started on a team that captured the small college national championship, beating Indiana State University. In the tournament games, Harmon had been singled out by several newspapers for his defensive play.

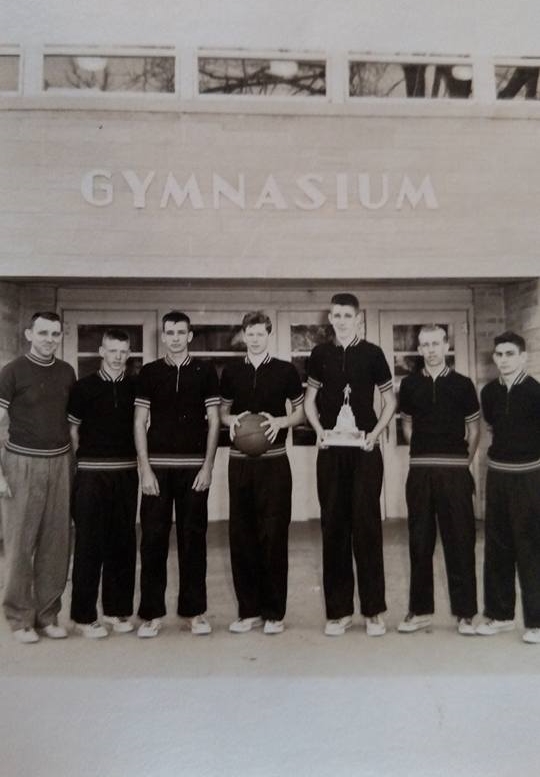

Wayne City would have been a typical starter school for a young ambitious high school basketball coach in Illinois. It had only 250 students and a cracker-box size gymnasium. Former player in the 1950s and later coach there, Bennie Greenwalt, remembered “the gym was totally wooden with a few rows of bleachers on one side. It might have held 300 fans.” Coach Harmon later told a sports reporter he “just went to Wayne City for a cup of coffee,” a phrase that captured the idea that a decent small-town coach could get a free coffee at any local eating place. Harmon added he mostly sought “a little experience coaching.”

At a minimum, a new coach such as Harmon shot for at least a break-even season, and one “big” win a season against a bigger school or a major rival. A lack of height, however, was almost always going to be an issue for small-town teams like Wayne City. This meant maybe having a six foot or a bit taller center and everyone else below that height.

Coach Harmon worked hard, seeing more than just solid success in his first three years. His second year’s achievements in the 1948-1949 season would have been enough to help him get to a bigger school if he had wished to do so. His Wayne City squad ended that year with a nifty 20-5 record. Those five losses were by two points each. His team then pushed big school Fairfield to the wire in the first round of regional play, Wayne City being ahead for most of the contest and losing by a single basket.

Still, it was no fun the very next season to have a decent year playing schools that were roughly the same size, only to run up against the biggest school in southern Illinois, Mt. Vernon, on its way to a second consecutive state tournament title. The Rams clobbered Wayne City in the first game of the regional.

The Wayne City Indians were a respectable 13-6 that year when the Mt. Vernon Rams, led by rugged 6-5 Max Hooper and four other starters at 6-3 or over, pummeled the Indians. A Mt. Vernon reporter went to the Wayne City dressing room at half time with the Rams up 33-4 and later wrote this report.

The Rams had done their job well. No graveyard at midnight was ever more quiet than the Wayne City room. The Indians were not just beaten—they were on the ropes. They’d answer the bell for the next round but they didn’t like the idea. A team that had won two-thirds of their games during the season without ever taking a lopsided pounding had been forced out of its class to windup the year. It was a sad way for some of those kids to close shop on their prep careers.

After the contest, Coach Harmon pointed out to one reporter that the height advantage was “something we couldn’t do much about.” Later, several Wayne City basketball “experts” figured Dick Harmon was surely ready to explore going to a bigger school where he might have a larger pool of students to draw from, and a greater number taller players.

And Dick Harmon just might have left if fate had not played an interesting trick on the young coach. At the beginning of the 1950-1951 school year, a red-haired freshman youth came walking through one set of Wayne City High School’s front doors. He almost had to stoop down to do so.

________________________________________

Jim “Red” Stutts was every bit of 6-5 and still growing. A member of a hard-working farming family, Jim had never played basketball before. But Coach Harmon watched him walking down the halls and in P. E. classes and assessed that “he moved pretty well for a boy that big.” Jim was also a lefty, a trait that was considered an advantage in basketball by many coaches. Harmon all but scooped the lanky kid up during the first week of school, telling Stutts he could help make him into a solid basketball player, if not a star.

Then, when Jim came out for the basketball team, coach made sure “he had a goal for practice on the farm.” By the end of that year, Jim Stutts had grown five more inches.

Mesmerized by what seemed to be happening before his very eyes, Coach Harmon suddenly had a dream that became a quest, a mission that held him at Wayne City four more years. He assumed young Jim Stutts bought into the same exciting vision. Harmon later explained to sports editor Merle Jones at Carbondale’s Southern Illinoisan, “A man might coach a lifetime and never come up with a high school boy almost seven feet tall. I’m going to stick in Wayne City until Stutts is out of school.”

Jim Stutts, Dick Harmon’s project boy, came along slowly. Despite Coach Harmon’s constant insistence on Jim increasing his food intake, for example, Stutts stayed around 160 pounds in his sophomore year. Nor would Stutts lift weights. Meanwhile, Wayne City struggled as a team too. They were 9-12 when they played a hot Bluford squad toward the end of the season, but Jim broke out for 12 points in the close contest. Coach Harmon could only hope it was a glimmer of things to come.

Two games later, the coach was brought back down to earth. Wayne City’s last game was in the regional, where the Indians went out in their first contest in a whimper, losing by 30 points to big-school Fairfield. The giant sophomore, Jim Stutts, was hardly a factor.

Of course, everyone said, “Wait until next year.”

________________________________________

The mess started with a letter which in turn begot another letter that brought about a bombshell. In the spring of 1952, just as Jim Stutts was finishing his sophomore year at Wayne City, a provocative sports report appeared in the Mt. Vernon Register News. Written by sports editor John Rackaway in his Sporting Daze column, the piece was explosive.

Mt. Vernon, the largest town in population in southern Illinois, was then a red-hot center for Illinois high school basketball, as well as for the highly popular semi-pro baseball in the region. In the spring of ‘52 the Rams’ basketball team stood at the very pinnacle of the Illinois high school basketball world, having won back-to-back state tournaments in 1949 and 1950 and gained the third-place trophy at the time of the letter’s appearance. As it turned out, one of the Mt. Vernon fans seemed to have wanted more. He was also apparently a person who was used to getting his way. It was this fan who sent a letter with a tempting proposition to the Stutts family, a single sheet of paper Jim Stutts’ parents took straight to Coach Harmon, handing it swiftly to the coach as if it carried a curse. Interestingly, the letter was signed.

A few days later, John Rackaway was reporting about a second letter, the one that created such a ruckus. “Here is a letter which we received yesterday from Wayne City High School,” Rackaway wrote. Then he wisely let that letter speak for itself.

Dear Sirs:

A Mt. Vernon fan has sent a letter to my tall center trying to influence him to come to Mt. Vernon to finish his education. I would not have thought anything about it if the letter had not been written by one of the most highly praised and respected men in Mt. Vernon and the United States. I have worked two years with Stutts, and now that he is getting to the place where he can help our team, other towns and coaches are trying to influence him to move.

The possibility of a town like Hebron or Wayne City ever going to the state is so small, the larger schools use this method of recruitment to influence players to go to their school. If the recruiting system starts on sophomores in high school, how could you expect a boy to keep from shaving points in college for a few dollars. If this trend continues in high school basketball it won’t be long before all good basketball players will end up in larger schools. There isn’t anything we can do about Mt. Vernon fans writing and talking to Jimmy about changing schools, but there is a lot we can think about these fans, and we are.

Yours Truly,

Dick Harmon, Coach

Rackaway did point out that he was certain there was no organized effort in Mt. Vernon to lure Stutts to become a Rams player and further stated, “The letter which Stutts received was written without the knowledge of [Rams] Coach Stan Changnon or Mt. Vernon school officials.” Merle Jones, at the Southern Illinoisan also mentioned the letter in a sports article, conveying the same information.

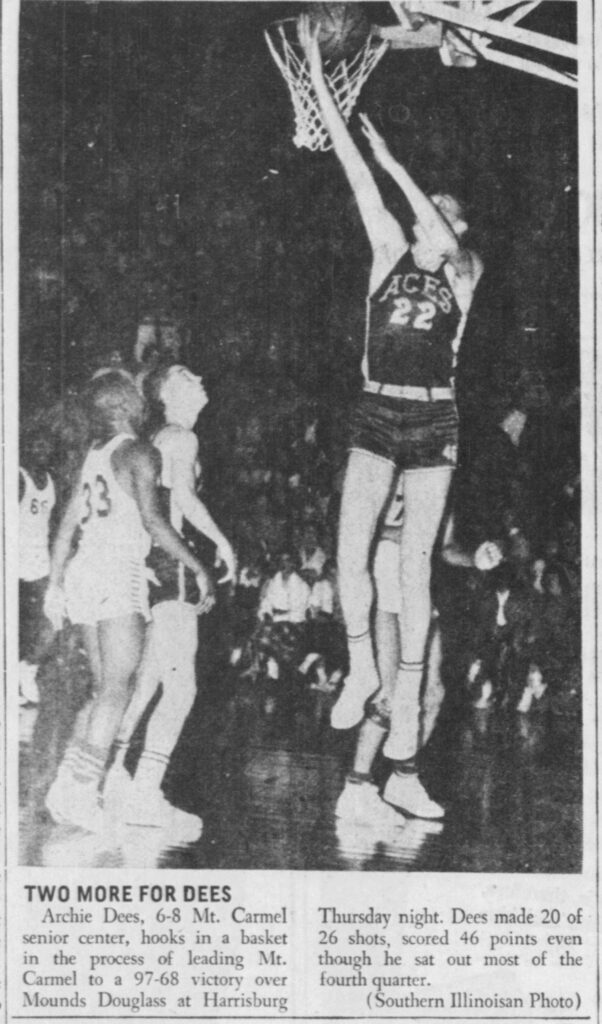

This type of controversy, by the way, was not unusual in the region. Big school Mt. Carmel, for example, would “steal” 6-8 Archie Dees from little Grayville High School that same year.

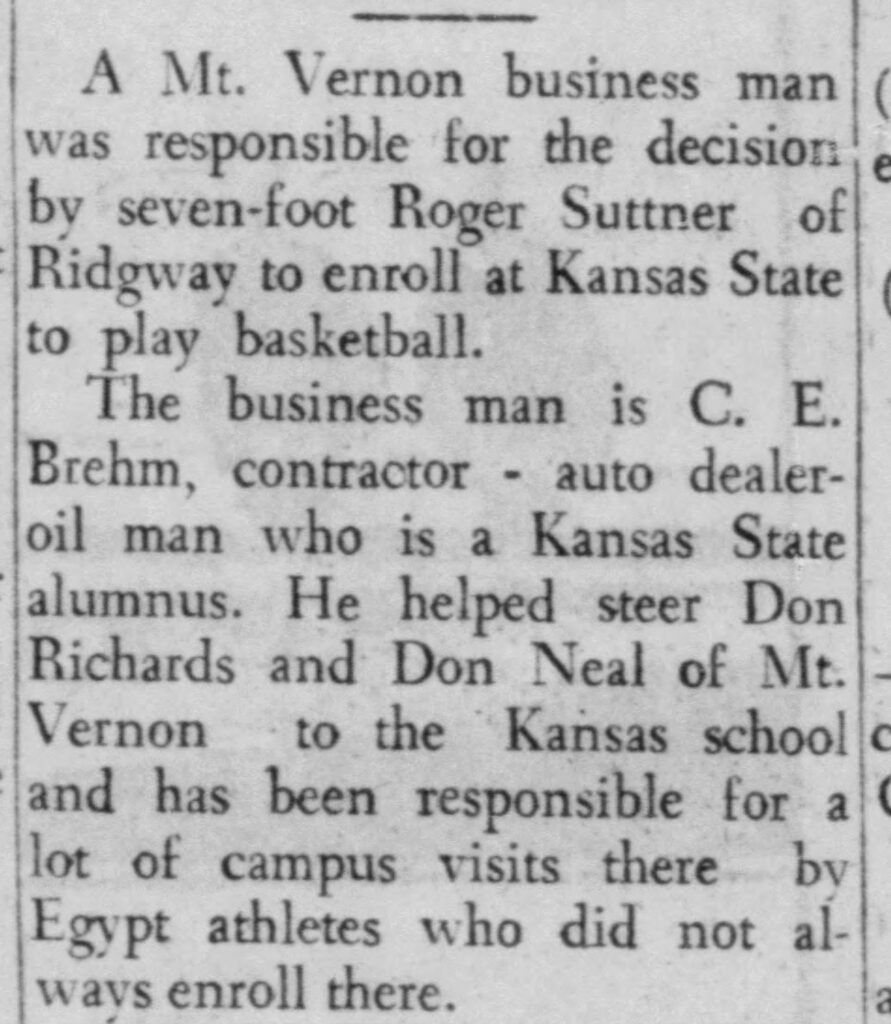

Coach Harmon never exposed the name of the prestigious Mt. Vernon fan who tried to steal Jim Stutts away from the Wayne City team, but one interesting possibility would be C. E. Brehm, the wealthy Mt. Vernon oil producer. Brehm was heavily involved in the semi-pro baseball network in the region and was a powerful supporter of Mt. Vernon High School sports. In fairness to the wealthy Mt. Vernon oil man, Brehm may have honestly been concerned about Jim Stutts’ future, believing that his last two years playing for Coach Harmon at tiny Wayne City, without a strong supporting cast of players to enhance Stutts’ development, would hurt his chances of playing in college. Had Stutts gone to Mt. Vernon, he would have had the opportunity in 1954 to have been on another Rams state championship team. Meanwhile, over the years, C. E. Brehm would offer to help other high school players such as Mt. Vernon basketball star Roger Yates and Rigdway High School’s own giant, 7-1 Roger Suttner, in getting into Kansas State. Yates, however, chose Southern Illinois University while Suttner did end up out in Kansas.

Whoever the instigator mentioned in the Mt. Vernon newspaper was, the Stutts family stayed loyal to their Wayne City community. More importantly, the newspaper letter incident made many basketball followers in southern Illinois perceive that Jim Stutts would likely develop as a player, one who might eventually dominate in the area basketball world. That kind of success, however, remained to be seen.

________________________________________

At the beginning of Jim Stutts’ junior season, a national sporting event further enhanced the interest in Stutts’ appearance in southern Illinois high school gyms. That event concerned the spectacular rise of college basketball player Bevo Francis and the mania which followed his performances. Stories of Bevo’s amazing shooting accomplishments at little Rio Grande College, made more awesome by his great height at 6-10, appeared in sports pages across the nation. So in demand was Bevo’s play, that the small school canceled many of their scheduled games with other small schools and rescheduled to play major university schools at the Cleveland, Ohio, coliseum which held 11,000 fans and at Madison Square Garden in New York City. In these contests, Bevo and his Rio Grande teammates defeated several big college teams of that time period such as Wake Forest, Creighton, Providence, and Miami, while losing by a single basket to Villanova. By the end of that season, gyms were filled with the chants of “Bevo, Bevo” every time the big guy got his hands on the ball. All of this led fans to become excited about any big-men basketball players who were more agile than in the past, and who could change the course of a game and a season.

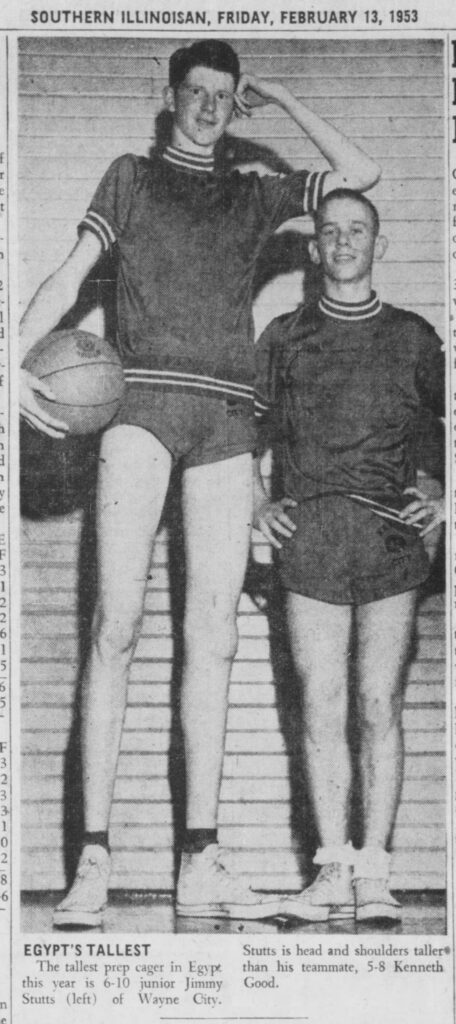

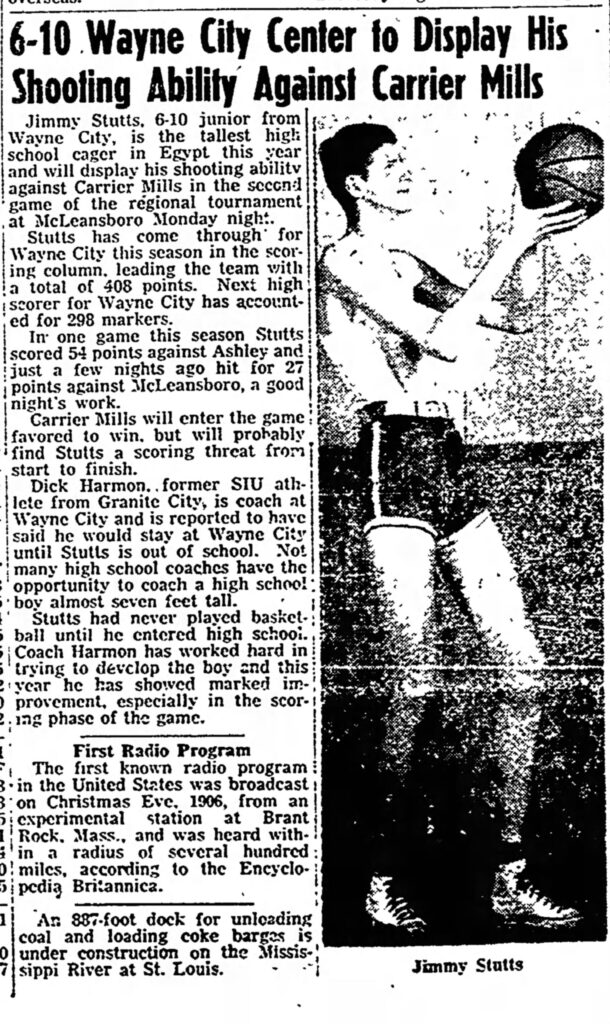

Meanwhile, Jim Stutts had grown another inch or so. Sportswriters now reported his height in a range from 6-10 to 6-11. One noted Stutts was the tallest basketball player in southern Illinois, while another added he was the tallest in the state. Certainly, the visual impact of Stutts’ presence on the gym floor was startling. Before Jim played, Coach Harmon’s other starters were at 5-9 tops. When Jim was on the floor with the team, the others’ lack of height made Stutts look like a giant from a fairy tale. Unfortunately, even with Jim in the game, the guards had trouble at the beginning of the season bringing the ball up the floor. To add to the coach’s personal frustration, the tall red-headed, left-handed player had not gained weight either. When underneath the basket, Stutts was often pushed around by shorter opposing players who liked rough physical contact.

But Jim Stutts worked hard and got better. He ended up averaging 20 points a game and the Indians finished up with a solid 15-7 record. During the latter part of the season, Jim Stutts really hit his stride, the Southern Illinoisan noting, “The tallest prep basketball player came up with the highest individual point total of the season last Friday when he scored 54 points against Ashley in an 88-46 Wayne City victory.” Just as amazing, the scoring onslaught was accomplished in three quarters. Several colleges were also looking at the now almost seven-foot player.

One bump in the road at this time, however, occurred in a game Wayne City played against a much bigger school, Granite City, Coach Harmon’s old high school. Granite City alumnus Harmon arranged the contest believing it would be a good experience for his team to play the kind of larger school Wayne City would meet when state tournament play began. Stutts and his fellow players were easily thumped 66-43.

Just before regional play, the Harrisburg Daily Register carried a nice spread about Jim Stutts’ solid junior year, noting, “Coach Harmon has worked hard trying to develop the boy and this year he has shown marked improvement, especially in the scoring phase of the game.” It was an uplifting thought to take into the first round of state tournament play. In their first encounter, the Indians would be facing a tough Carrier Mills team that ended their regular season at 17-5 after playing stiffer competition than Wayne City. Coach Harmon was confident, however, sensing his team was going into the contest with a bit of momentum.

At first, things went badly for the Indians. The Southern Illinoisan noted, “Wayne City, featuring 6-10 center Jimmy Stutts, looked helpless against the press the first quarter as the Wildcats ran up a 21-11 lead.” It was the curse that had followed them almost the entire year, a lack of good ball handlers. The Wildcats “were stealing the ball repeatedly the first quarter.”

Then, miraculously, the Wayne City players began breaking the press and the game turned into a slug fest.

Carrier Mills was only up 36-28 at halftime, and Coach Harmon told his team to just keep grinding away, that they needed to play hard to the very last second if they hoped to win. And grind they did. The Indian hopes soared when Wildcat ace Den Farrar fouled out with 6:35 to play and Carrier Mills led by only 60-54. The Mt. Vernon paper reported the next day that “Jim ‘Splinter’ Stutts shoveled in 12 points” for Wayne City in the rugged third quarter frame. Unfortunately, Stutt fouled out half-way through the climatic fourth quarter, and Carrier Mills went on to win, 76-67. For the game, Stutts ended up hitting all seven of his field goal attempts and ended up with 16 points, while teammate Bill Bassett canned over half his attempts for 27 markers.

Next day assessments by sportswriters suggested the things the Wayne City giant needed to work on for the next year. The Carbondale paper, for example, noted his limited agility, pointing out that his seven field goals all came from “shots from his stationary post to the right side of the basket.” A Mt. Vernon sportswriter noted that “The angular Stutts was adapt at popping the ball in when his mates could hit him with a high pass, but his rebounding was less than spectacular.” Carrier Mills’ freshman center, for example, “repeatedly snatched rebounds out of Stutts’ arms.” The Register News also stressed that “The fast-breaking Carrier Mills club had a little too much polish and experience for 6-10 Jimmy Stutts and Coach Dick Harmon’s Wayne City Indians. In the end it was superior rebounding which brought the Millers into the winner’s circle.”

Finally, the Dean of sports reporters in southern Illinois, Merle Jones of the Southern Illinoisan, shared his candid, precise, and thorough judgements in an article titled Egypt’s Tallest Cager Just a Big Boy Now.

Jimmie Stutts, a 16-year-old Wayne City Junior who at 6-10 is the tallest cager in Egypt, still has a long way to go to become anything approaching college material. Jimmie weighs only 165 pounds and looks like the usual beanpole. I saw him for the first time Monday night as his team lost to Carrier Mills 76-67, in the McLeansboro regional.

The red-headed Stutts played a stationary offensive post just to the right of the basket throughout the game. That seemed the wrong spot for him, since he is left-handed and would have more protection for his shot from the other side. But a boy as tall as Jimmy doesn’t need much protection. And I must say the boy knows how to put the ball through the basket. He took seven shots and made seven baskets. Four of the baskets came after the ball had been lobbed to him over the heads of the defense. Another came on a tip, one on a rebound and one a setup from a quick pass.

Carrier Mills kept two men on Stutts all the time. Oliver Rollins, the Wildcat freshman center, did a good job of rebounding and knocking down the passes thrown to Stutts or he would have even scored more points. Stutts is still slow in handling the ball. Several times he tried to shoot, and the ball was knocked out of his hands.

Coach Harmon added another issue when he was interviewed by Jones. “We have been under a handicap on a big floor. Our gym is small and so are the gyms of many of our opponents. But we are getting a new gym next year and maybe that will help.”

Then, perhaps thinking of the future, Harmon explained, “In the last few games Stutts has been moving around the basket a little more and has a pretty good hook shot. But most of the time he just stands under the basket, the boys lob the ball to him, and he makes them.”

Looking back at 1he 1952-1953 season, Coach Dick Harmon and Wayne City fans probably had mixed feelings, although, overall, the year had been fruitful. The next year, with some promising ball handlers coming up, promised to be even better. Many thought, including Coach Harmon, that Jim Stutts, the Wayne City giant, would finally have a breakthrough year, followed by many college offers.

________________________________________

In the early fall of 1953, it became apparent that something had happened between the end of Jim Stutts’ junior year and the time that basketball season rolled around. Stutts, who now stood 6-11, was missing from the roster in the first six games. Finally, Merle Jones at the Southern Illinoisan had the scoop. “Jimmy Stutts, Egypt’s tallest basketball player at 6-11 is back in the good graces of Coach Dick Harmon of Wayne City and is ready to play again. Stutts, now an 18-year-old senior, was missing as Wayne City lost five of its first six games. His absence led fans and coaches to speculate that some other school had enticed him to move.” Dick Harmon gave more detail, telling Jones that Stutts “has been here all the time. But he violated training rules and wouldn’t practice properly before the season began so I dropped him. Then he had a change of heart and has been working to get ready. He is six weeks behind, however, and may be two or three weeks in getting in shape.”

Merle Jones also offered up his own observations about the Wayne City team without the presence of their giant. “Harmon has been starting a first five with four regulars 5-9 and a fifth man, a freshman, a mere 5-1.” Coach Harmon also added that the year before his team lacked a good back court. “This year I have two fairly good boys out front, and we should fare better the rest of the season.” Two underclassmen on the Wayne City team clearly remember playing with the tall red head. Max Allen recalled, “Jim was 165 lbs. of sharp elbows.” Another freshman, 5-1 Bennie Greenwalt, recalled his job “was to bring the ball down the floor and lob it into Jim near the basket for him to shoot.” Three years later, as a senior, Greenwalt would be much taller and the Indians’ best player.

Jim Stutts’ progress surely pleased his coach, who had carried a dream for four years that he could help turn Stutts into a player who would catch the wishful eyes of college coaches and lead Wayne City to a great regular season and maybe a few games into state tournament play. Of course, Harmon’s own coaching future would certainly be enhanced if this happened.

During Christmas break and on into January, Jim Stutt seemed to get better each game. He had 28 in Wayne City’s third place win in a big holiday tourney then garnered 32 hard won points in a close loss to archrival Bluford. The Harrisburg Daily Register reported that in the next game Stutt hit for 35 points against St. Francisville, his best effort yet that year. When Wayne City played an exceptional Grayville squad, a team that had the best winning record in the state at that juncture and one that had beaten Wayne City handily earlier in the season when Stutt wasn’t playing, Jim scored 31 points in a near upset. Sportswriter John Rackaway wrote that Stutts’ play that night “demonstrated how one big man can carry a prep team.”

Late in February, Jim’s scoring against Crossville brought him “the highest game scoring for the season in southern Illinois.” He poured in 50 points on 20 field goals and 10 foul shots, according to the Mt. Vernon Register News. But the sweetest win, at least by Coach Harmon’s standards, was yet to come.

In late February of 1954, just before Wayne City was scheduled to face McLeansboro in the first regional game in the Mt. Vernon High school gym, Dick Harmon took his team back over to big school Granite City near St. Louis. As noted, the year before Wayne City had been blasted by Granite City. In 1954, however, the outcome was different.

The next day after the contest, John Rackaway wrote in the Register News, “Dick Harmon was a mighty jubilant guy when he called us this morning. His Wayne City Indians beat Granite City last Saturday night 66-64 in an overtime.” Coach Harmon explained over the phone to the Mt. Vernon sportswriter, “They hit us with full court press, and, for the first time, we were able to work well against it. If we can do Wednesday night as well, we should give McLeansboro all they want—and maybe more.” Rackaway, however, pointed out in his sports report that McLeansboro had easily handled Wayne City earlier that year, 68-44. Harmon, on the other hand, could take comfort in knowing that Stutts had yet to hit his stride at that time.

Wayne City was 12-12 going into the state tourney against McLeansboro, but probably would have been 17-7 had Jim Stutts been playing the entire season. As it turned out, the night was one of magic for the Wayne City giant.

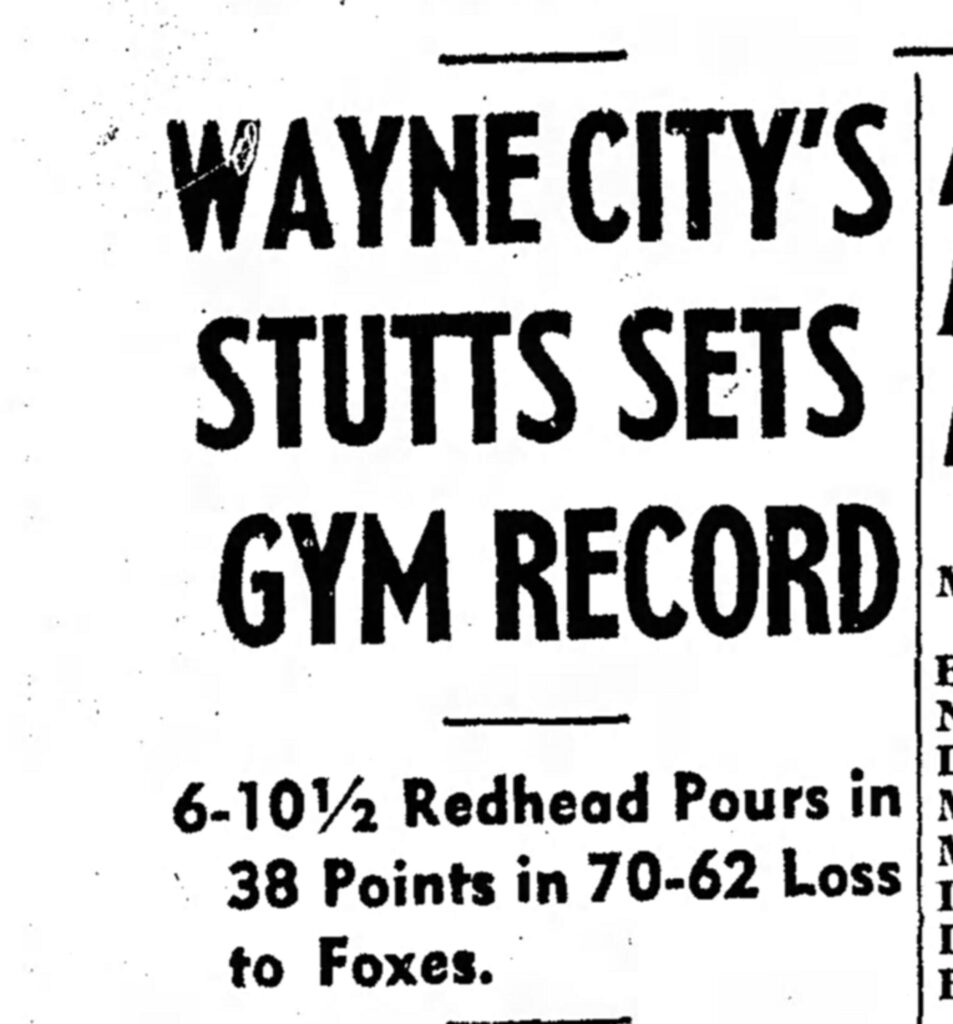

The first quarter saw McLeansboro up by only two, 16-14 and up at halftime, 28-26. In the third quarter, Jim Stutts couldn’t miss, and Wayne City went up by three points that quarter until the Foxes came back to take a small lead. One newspaper reporter noted, “The manner in which the lanky Wayne City lad stuffed ‘em in had the crowd yelling “Bevo! Bevo!—and made the Indians a sentimental favorite against the more polished Foxes.”

McLeansboro eventually gained back the momentum, winning 70-62. Jim Stutts, meanwhile, left everything on the playing floor, hitting 13-19 field goals and 12-15 foul shots for a total of 38 points. More amazingly, he broke the Mt. Vernon gym scoring record set by the great Max Hooper of 36 points. It was a stunning way to end a career.

Then came the shock. After the season ended, Jim Stutts revealed that he did not want to go to college, even though he had signed to play at Memphis State. This loss of interest might have explained his refusing to follow some of the rules in practice at the beginning of the season and being dismissed from the team. Teammate Bennie Greenwalt recalled that Stutts “wanted to get out into the work force and went up north to get a job at the Caterpillar Plant in Peoria, Illinois.”

________________________________________

The dream, indeed, the mission Coach Dick Harmon took on of helping develop Jim Stutts into a great Illinois high school basketball player, the kind of solid player that colleges would go after, took its toll. Harmon announced he was leaving Wayne City at the end of the school year shortly before regional play. He played down his leaving, simply saying to John Rackaway at the Register News, “After seven seasons I do not feel that I am getting anywhere. I’m just going to cut loose and try to find another job. If I don’t get a better one, I’ll get out of the coaching business.”

Most sportswriters, however, perceived Harmon’s effort as a sad failure. The Southern Illinoisan explained, “When Stutts entered high school four years ago, he was 6-6 and still growing, but the dream Harmon and the Wayne City fans envisioned when they first saw the boy never materialized. Stutts graduated this year after having been no better than average as a high school basketball player, and Harmon, after four years of dreaming and hoping, will take his leave too.”

Some sportswriters even pictured the episode as a tragedy. Writing just before the season ended, but after Harmon had announced his leaving the Wayne City job, Merle Jones called it “the end of the trail and the end of a dream,” adding, “Perhaps Dick can be forgiven his delusions of grandeur when he first saw the tall freshman. Stutts is a senior this year and Harmon isn’t going to win the state title with him. In fact, Wayne City can’t even beat some of the schools Harmon used to beat before he ever saw Stutts.”

Life, of course, went on. Coach Harmon got the head coaching job at Granite City, likely because of the Wayne City team’s victory against the bigger school in Stutts’ senior year. Wayne City came out in good shape as well, hiring a grade school coach in the system, Conrad Allen, who led the Indians back to basketball glory in the school’s new full-size gymnasium. Coach Allen quickly established a 16 team holiday tournament that became the premier Christmas tourney for small schools in southern Illinois. Before long, Wayne City was a major player among small school teams in the region.

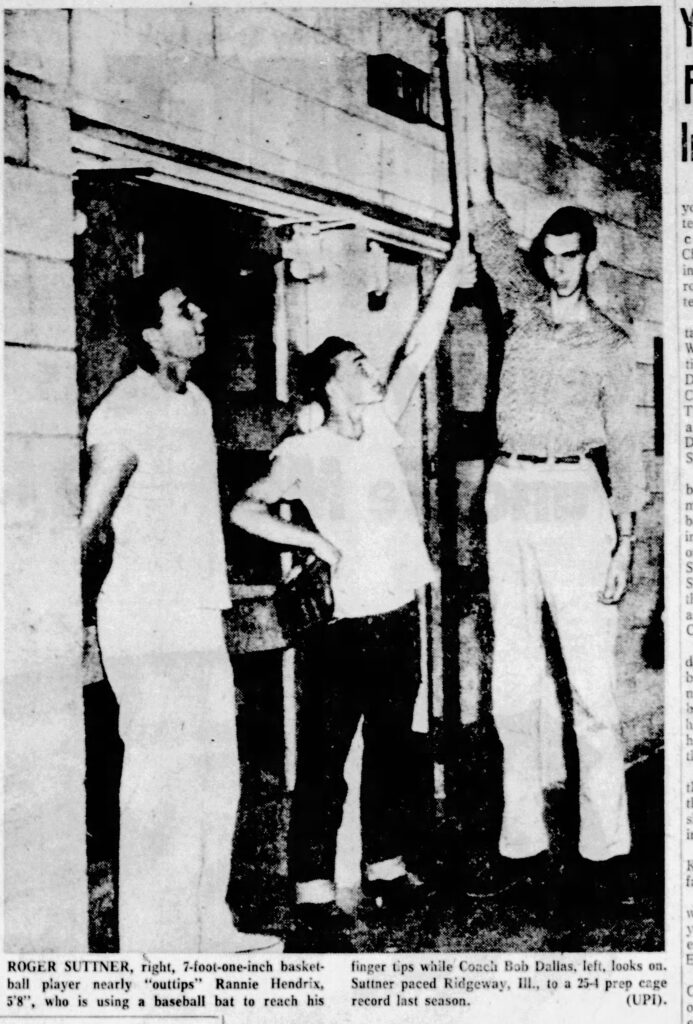

One last side note. Jim Stutts’ story also ended up being a cautionary tale when another 7 foot lad came along at Ridgway High School in southern Illinois just after the Wayne City giant played basketball. His name was Roger Suttner and his arrival as a 6-5 freshman at small-town Ridgway caused warning bells to go off among southern Illinois sportswriters. The curmudgeon, Merle Jones, pointed out, for example, “Not all tall boys become basketball stars. A couple of years ago it was 6-11 Jim Stutts of Wayne City who caught the eye. He failed to develop very well, however.” Jones needed not to have worried. Suttner grew to 7-1 and became a force on the basketball floor, setting single game scoring records and leading his team to phenomenal seasons. Then with the help of Mt. Vernon’s influential C. E. Brehm, Suttner ended up at Kansas State.

All of these events happened over sixty-five years ago, long enough to be pretty much forgotten today. Still, it is interesting to be reminded that giants once strolled not through the woods, fields, and hills of southern Illinois, but rather in the fan-packed gymnasiums, large and small, that dotted the landscape in the 1950s.

Perhaps too, these giants still occasionally haunt the region, looking in confusion for gyms that are no longer there, hoping again to capture just one more moment of high school basketball glory.

Sources for this work include Carbondale’s Southern Illinoisan, Mt. Vernon’s Register News, and Harrisburg’s Daily Register. Interviews were also taken with Roger Yates, Bennie Greenwalt, and Max Allen.