This story centers on the time before large-scale school consolidations, class basketball, and a three point line, these changes having occurred roughly by the turn of the last century.

The state of Indiana has long claimed to be the true center of high school basketball, especially when Indiana state tournament time rolls around. It was not so much that Indiana fans thought they always had the very best players, although they could certainly mention Oscar Robertson or Larry Bird. It was that Hoosiers believed their high schools demonstrated the most exciting style of play with perfect execution, and with crowd exuberance that bordered on madness. All of this was grounded in high school gymnasiums large and small across the state. An outsider traveling through some parts of the state might easily believe some of these gyms were castles, if not shrines. Fourteen of the largest 16 high school gymnasiums in the nation are in Hoosierdom.

Tom Tuley, a former Evansville Press sportswriter, did a pretty good job of capturing the essence of the thing in 1971 when he described a Indiana small-town team’s journey deep into the state tournament as “a trip to the moon, a ride across the heavens on a crazy thunderbolt, lightning bottled in a jug, a community gone mad.”

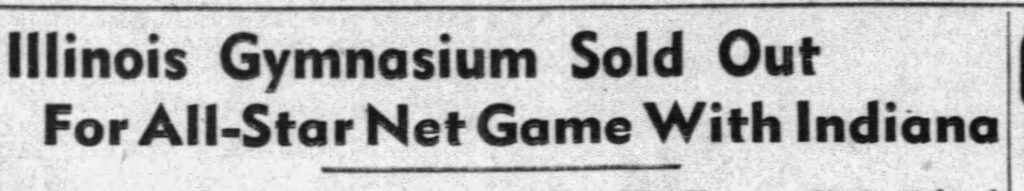

Not every state has accepted Indiana’s claim to this title. Kentucky high school basketball, perhaps, has been Indiana’s greatest rival over the years. Kansas claimed the title for a while, and so forth. But buried in the passage of time is one state that briefly challenged the notion of Indiana high school basketball supremacy in an undeniable manner— Illinois. This latter controversy came to a dramatic head in a sold-out basketball game at the Mt. Vernon, Illinois, high school gymnasium in August of 1942, but not before a lot of steam was built up by sportswriters in both states. It was a doozy of a battle in that hot, summer-heated gymnasium, “the first clash ever staged between the best high school players of the two most cage-mad states, Illinois and Indiana,” as one sportswriter noted. In that throng were sportswriters from across the region and the nation.

The contest, however, was a long time in gestation.

_________________________________________

By 1920, better transportation and communication were drawing states and the nation closer together, to the point that sports at all levels would enter a golden age of expansion and importance. And it just kept snowballing. Most every town carried a sports page with a colorful sports editor who further raised interest in local teams, especially when it came to high school basketball. Communities large and small backed their teams in a spirit that approached fanaticism. Soon, competition erupted in the form of newspaper articles in various states, all of them bragging that their level of basketball was the best in the nation.

Designating the state with the best high school basketball play, however, seemed impossible until 1917. That year athletic director Amos Alonzo Stagg at the University of Chicago put together a national championship tournament showcasing the best high school teams in the nation, the Annual Interscholastic Basketball Tournament. Evanston, Illinois, High School won the first year, establishing a strong Illinois claim to having the best high school basketball in the country.

The tourney was shut down by the great flu epidemic for two years then exploded into an activity of national interest in 1920. And Indiana high school basketball would finally be placed on the national map, although through an unusual set of circumstances.

Two Indiana high school teams, bitter rivals Wingate and Crawfordsville, had ineligible players on their rosters at the beginning of the 1919 playing year, and both teams were suspended by the Indiana High School Athletic Association (IHSAA) for the season. The two “outlaw teams,” as they were called in Indiana newspaper articles, continued to play independent teams in state and in out of state tournaments. And they ended up playing for the “national” championship at Chicago in 1920.

Wingate won. Newspapers all across the nation made a big deal of the two finalists being Hoosier high schools, the first national suggestion that Indiana high school basketball was tops in high school play.

In the 1920-1921 season, West Layfette and Jeffersonville, both Indiana teams, played in the national Chicago tourney after being knocked out of the Indiana state tournament. West Layfette made it to the semi-final round, beaten by the eventual tourney winner, a high school squad from Cedar Bluff, Iowa.

The next year the IHSAA banned Hoosier high school teams from playing in out-of-state tournaments. This policy did not go unnoticed. A Chicago sports reporter complained in 1925 of Indiana’s absence, noting, “Indiana is one of the greatest basketball centers in the United States and it seems unjust not to let the leader compete in at least the [Chicago] interscholastic.” Then the writer added, “Maybe it is fortunate for the contestants that there was no Indiana school taking part.” (The Chicago tournament would end after the 1929-1930 season.) Meanwhile, in 1925 a well-represented national tournament was won by a Kansas high school squad out of Wichita. The afterglow was predictable.

but the claim would not hold up for long.

In the early spring of 1925, a Kansas newspaper declared the state “The basketball capital of America.” The story was picked up by other newspapers across the nation. The article pointed out the state had won the national A.A.U. title, the state’s flag ship university had a record of 61 wins out of 64 games in the last four years, and Wichita High School had captured the national high school title at Chicago. “And, to further the prestige,” the article finally bragged, the inventor of basketball, James Naismith, “has been a professor at the University of Kansas for many years.”

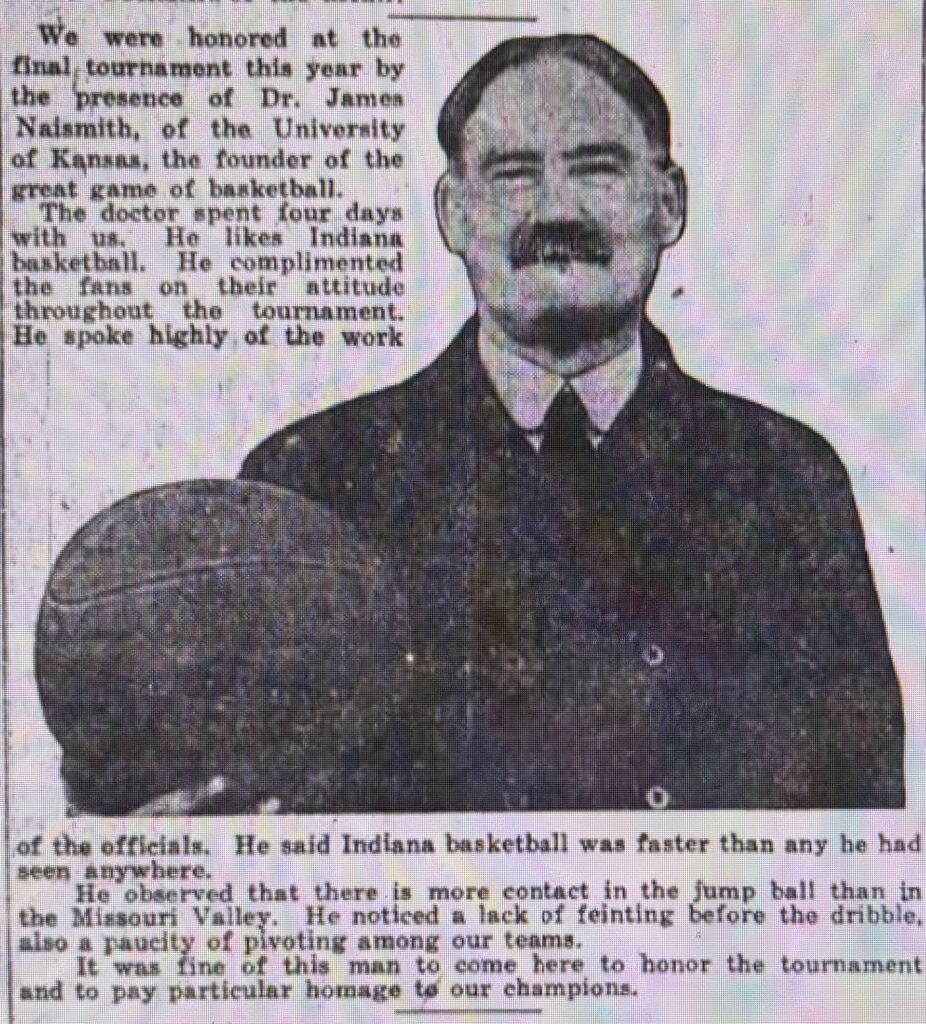

In fact, Naismith had traveled to Indiana that very spring, having been invited by the committee that ran the basketball state tournament to see how the game was played in Indiana.

________________________________________

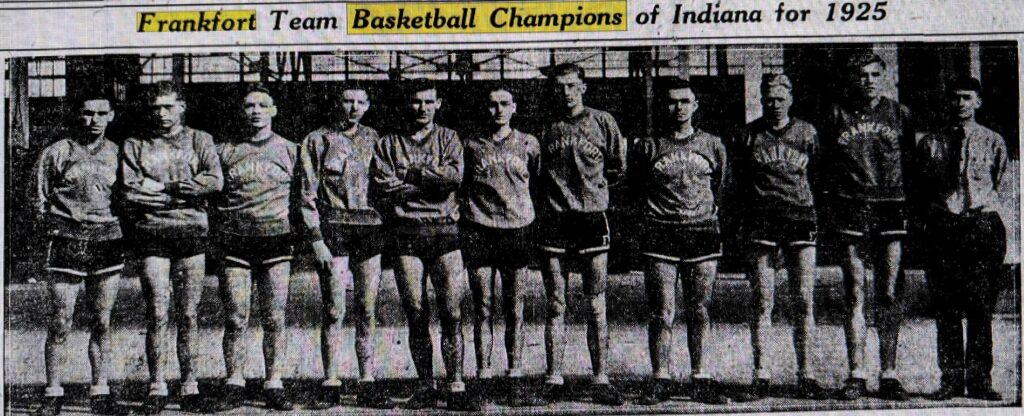

James Naismith attended four long days of Indiana high school state basketball games at the cavernous state fairground’s Exposition Building in Indianapolis. It was an awesome, noisy, electrifying experience, the building packed to overflowing with screaming fans for every contest. One sports reporter observed how Naismith sat like an aged (he was 64) and proud father “on a little bench at the northeast end of the playing floor,” watching the intense games unfold. What he saw amazed and pleased him. His invention, his “child,” brought into the world just 34 years ago had grown to become a colossal pageant, beyond words.

In the championship contest between Kokomo and Frankfort, Naismith witnessed 17,000 screaming fans being completely captivated by the ten young men running on a gym floor with a single ball being thrown around. Naismith told a reporter he was amazed by the fact that “the crowd was not entirely made up of youngsters, and that hundreds of others besides parents followed [their] school’s basketball closer than a carriage follows a horse.”

A Muncie Star Press sportswriter caught Naismith laughing “heartily as cheer leaders turned somersaults. He shook his head in admiration as a forward went under the basket to score one of those Indiana made-under-the-basket shots. Naismith turned to his neighbor and told him, ‘it was the best he had ever seen.’” Another reporter was told by Naismith that “Indiana basketball is faster than any I’ve seen anywhere.”

But it was the action of the crowds, their total, wild absorption that really mystified basketball’s founder. And then came Naismith’s own awareness of how he himself was moved to join them in frantic cheering. It was an experience somewhere between magic and divine revelation. Naismith, when he calmed down, declared the game was invented in the east, but Indiana was by far “the center of the sport.”

There was yet another outside expert observer at the state tournament who also spoke to Indiana high school’s high level of play that year. Walter Meanwell, the coach at the University of Wisconsin, was shocked and pleased, noting, “I went there expecting big things, but it astonished me. It was the greatest exhibition of athletes in the United States I have ever seen.”

So much for Kansas. Both James Naismith, the father of basketball, and Coach Meanwell at the University of Wisconsin had anointed the Hoosier state as playing the best high school basketball in the country. Now other states would have to catch up.

_______________________________________

The sense of Indiana dominance when it came to high school basketball continued to grow among Hoosiers. By 1929, the term “Hoosier Hysteria” was used to capture the intense interest and energy that revolved around Indiana state tournament play, the Indianapolis Times noting, “The big Hoosier hysteria started today. The zero hour? When your team is behind, and the gun goes off.” In 1931 a Hoosier sportswriter used the term March Madness to capture the essence of high school state tournament play. This is the oldest use of the term this research found.

Even during the dark days of the Great Depression, Indiana high school basketball reigned supreme. One Muncie newspaper captured this phenomenon in 1932. “Despite present economic conditions, goodly crowds attend the opening games, for basketball is dear to the heart of the average Hoosier. They might go without shows, candy, or other luxuries, but they must have their basketball.”

In 1940, a Muncie, Indiana, newspaper bragged that the Hoosier state had “captured seven national championships in the season just ended,” proving that the state was the “hotbed of the game in the United States.” These victories included Indiana University’s first NCAA title, an Indiana Catholic high school winning the National Catholic High School Basketball championship, and an all-black Hoosier high school winning a national title. By this time, the state proudly carried the reputation, as one sportswriter humorously noted, of a Hoosier “baby’s first playthings being a rattle and a basketball.

There were pretenders to the throne. After winning the national championship at Chicago, the state of Kentucky, for a while, claimed its state played the best high school basketball. Indiana high school fans were made even bolder in their claim for that spot when they began playing neighboring Kentucky in an annual high school All-Star game. The Hoosiers won the first contest by a basket in 1940 and crushed the Kentuckians the next year, leading sportswriter W. W. Fox to boast, “Their horses may be faster, their whiskies mellower and their women more beautiful but with all their Colonels and their blue grasses those Kentuckians can’t produce anything to cope with us Hoosiers in basketball.”

But all was not completely well with the argument of Indiana’s dominance. Towards the end of the 1930s, the lives of three individuals in Illinois were converging in a way that would present the greatest threat to Indiana’s claim as the best state for high school basketball in the nation. Ironically, two of these men were native Hoosiers.

______________________________

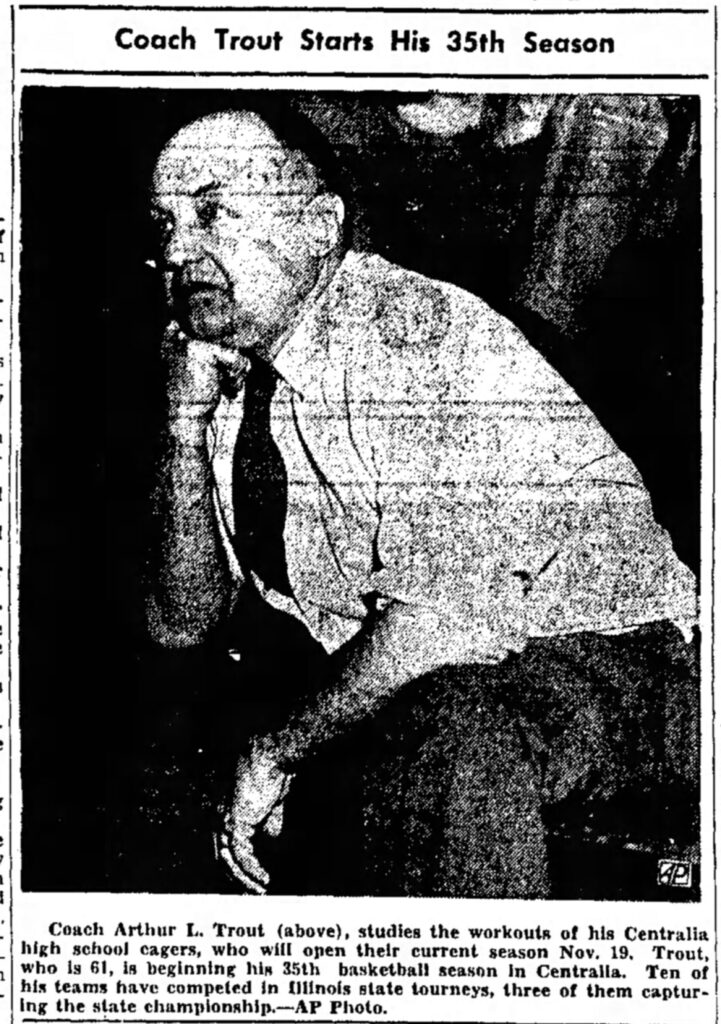

Arthur Trout grew up in Bruceville, Indiana, in the poorer southwest region of the state. His father was a Christian Church minister and Latin teacher who encouraged his son to read classic literature. Ambitious to achieve something beyond what he might do in the environment of his youth, Trout entered Indiana University where he earned a degree and a teacher’s certificate. While at Bloomington, he played halfback on the Indiana University football team and met his future wife. Fate, however, brought him to Illinois. He began his first and only teaching/coaching job at Centralia, Illinois, in 1914.

Eccentric, set in his ways,Trout nevertheless created the so-called “Centralia System” that brought quick success. His teams won state basketball championships in 1918 and 1922. He rarely experienced a season below twenty wins and took Centralia teams twice to the Chicago national tourney during the decade of the 1920s. In the 1938-1939 season, Centralia was on the cusp of its greatest four year run, a streak that brings another essential individual into the story.

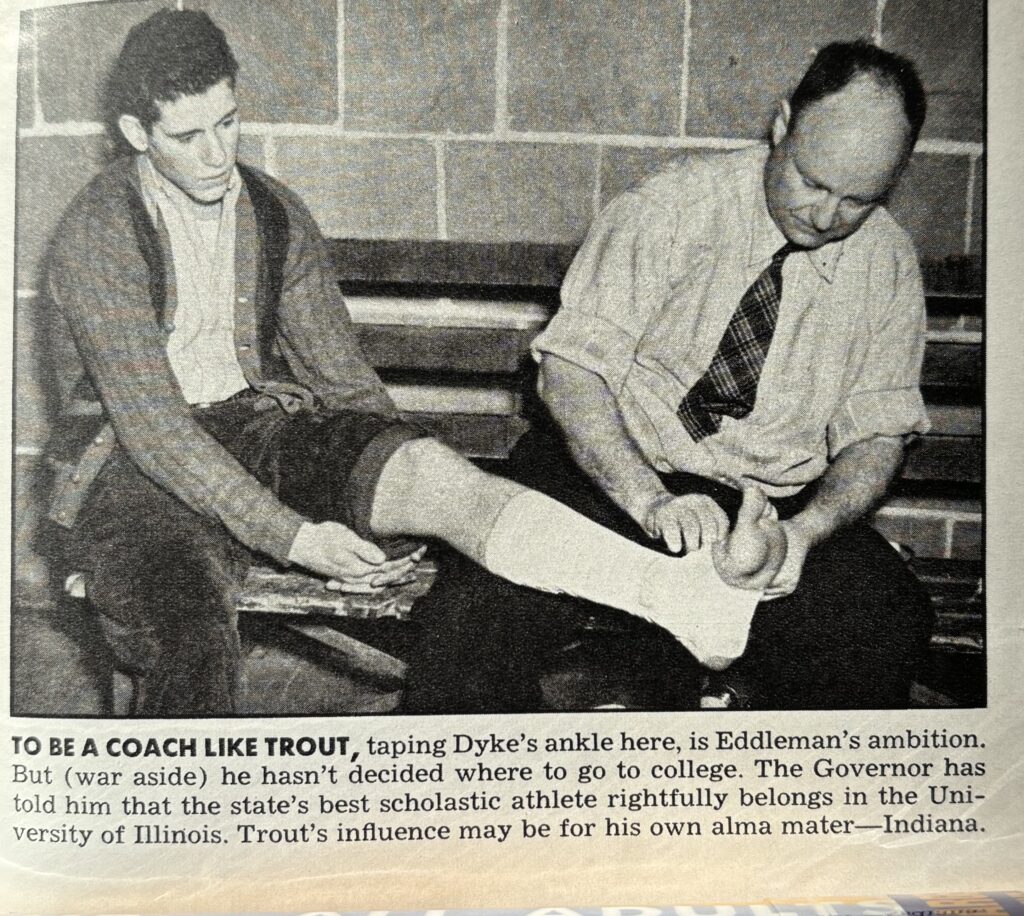

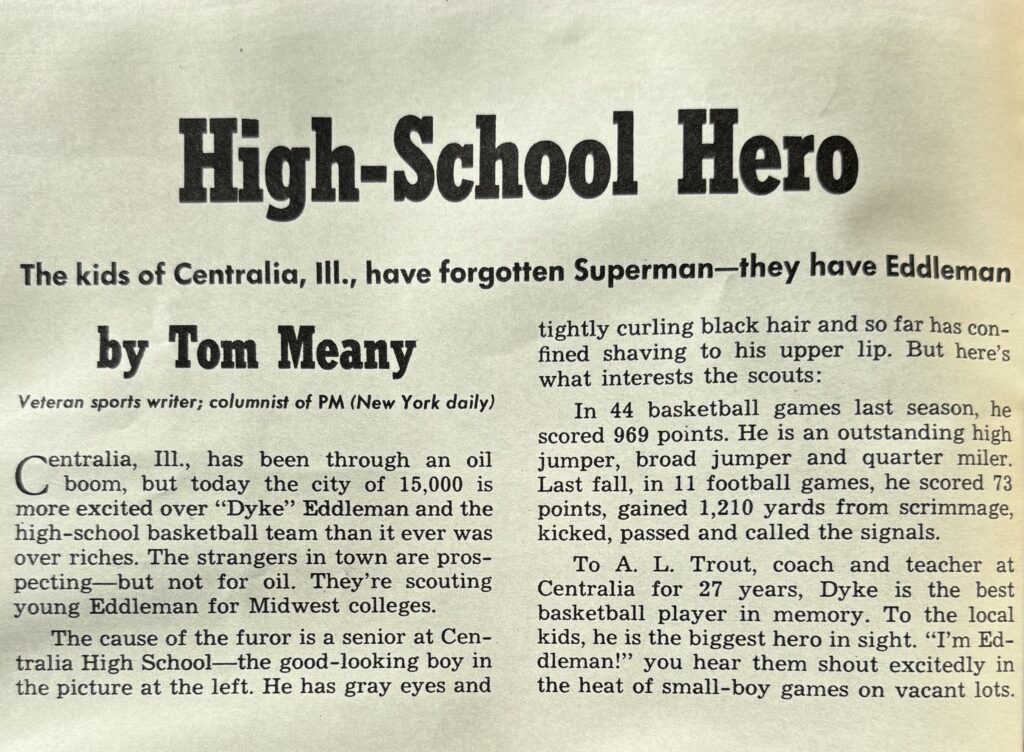

Centralia made it to the final four level in 1939, and a Centralia freshman, Thomas Dwight “Dike” Eddelman, (sometimes spelled Dyke) shocked the state’s basketball world when he set a record for points in a single game on the state tournament level. The Decatur Herald called the feat “An almost unbelievable barrage.”

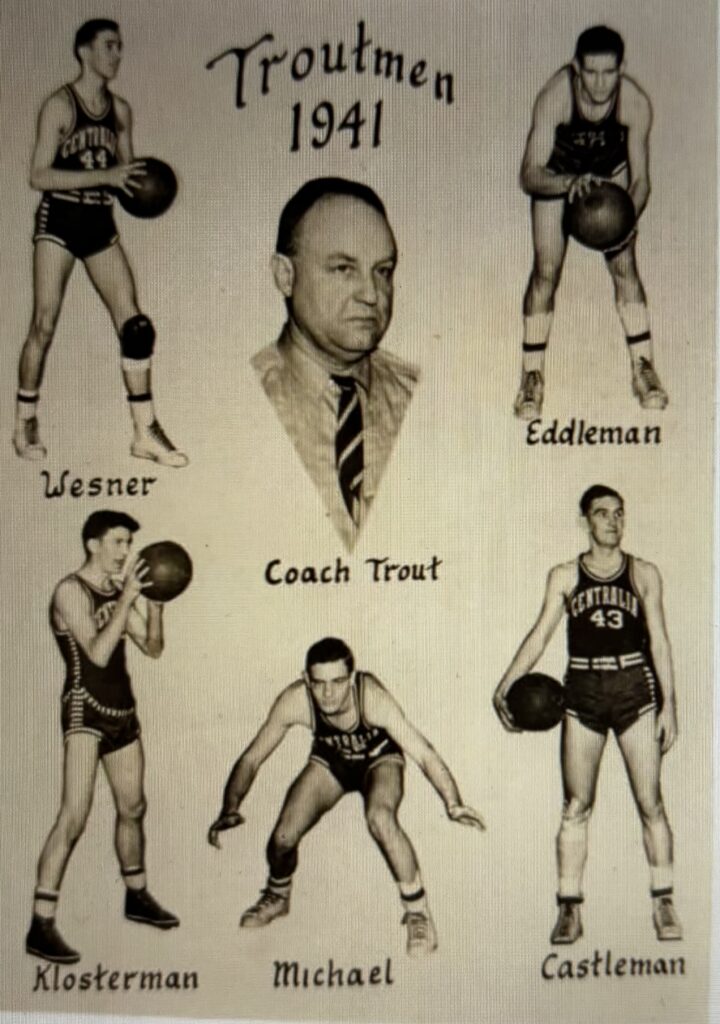

In Dike’s sophomore year, county rival Salem beat Centralia in the finals of the sectional. However, Eddelman still managed to come in second in the race for the state’s season scoring record, barely beaten by a senior player. In one game that year he scored 42 points. Then came Dike’s junior year, THE year for Centralia. Eddelman played with four highly skilled seniors, and they won 42 games in a row going into the semi-finals of the state tournament. They were crowned “the Wonder Five” and were picked to easily win the state crown. Even Indiana was forced to take notice. “Centralia,” one Hoosier sportswriter warned, “is an outfit even a Fiji Islander could go ‘nuts’ about.”

Hoosier high school basketball experts were beginning to worry too that Illinois, at least in terms of the Centralia squad, had caught up to Indiana’s level of play and excitement. One Hoosier newspaper sent a “skeptical committee of self-styled basketball experts” to the Mt. Vernon, Illinois, sectional final game in 1941 where the host school, the Mt. Vernon Rams, faced the Arthur Trout led team. A member of the group came back with an amazing report, one that grabbed many a Hoosiers’ attention. “A portly fellow from Indiana sitting behind me last night at Mt. Vernon Township High School’s well apportioned gym said, ‘I have never seen anything like it.’” The reporter turned and said, “What do you mean you’ve never seen anything like it? You’re from Indiana, aren’t you?” The Indiana man replied, “I’m from Indiana and I see plenty of Indiana basketball. But I’m telling you that I have never seen anything like it.” By the end of the game, the sportswriter totally agreed. The “Centralia System” simply dismantled their foe.

At about this same time, an Evansville, Indiana, paper called Centralia “the number 1 high school basketball team in the nation.” It was not a happy thought for any red-blooded Hoosier.

But then fate played a mean trick. The Wonder Five came crashing down. They lost in a semi-final contest in the 1941 state tourney, losing to Morton by a single point. At the time, it was called the greatest upset in Illinois high school basketball history. After the shocking loss, Eddelman “wandered around the floor in a daze before he finally headed for the exit.” Centralia’s unexpected defeat was also reported in newspapers across Indiana. Many Hoosiers breathed a sigh of relief. Neither Centralia nor Eddelman now seemed as great as advertised.

Dike Eddelman was playing with a lesser cast at Centralia his senior year. The team was 29-6 headed into the state tournament, with several narrow escapes in the regular season. Eddelman, however, was playing out of this world. Toward the end of Illinois’ high school basketball season, the Rock Island, Illinois, Argus bragged how Centralia had “achieved new heights” based primarily on Eddelman’s unbelievable play. “The citizens of this state can now take their basketball so seriously that Illinois may be regarded as a challenger to Indiana for the title of the nation’s basketball capital. The height of the basketball daffiness is currently described as Eddelmania. It is characterized by such morning-after habits of asking the question, ‘How many points did he make last night?’”

Eddelman led his team to a state championship with an incredible last second shot, and his achievements that year made him a god in Illinois and eventually in the region and the nation. In a four-page Look magazine article, Eddelman was presented as The High School Hero, a basketball star like no other.

Hoosiers wept.

________________________________________

While Dike Eddelman, Arthur Trout, and the Centralia crew were creating new basketball legends in Illinois during the 1941 and 1942 years, an Indiana high school team was creating basketball legends of its own, establishing a two-year reign as powerful as Centralia’s in Illinois, although the journey started out on a sour note.

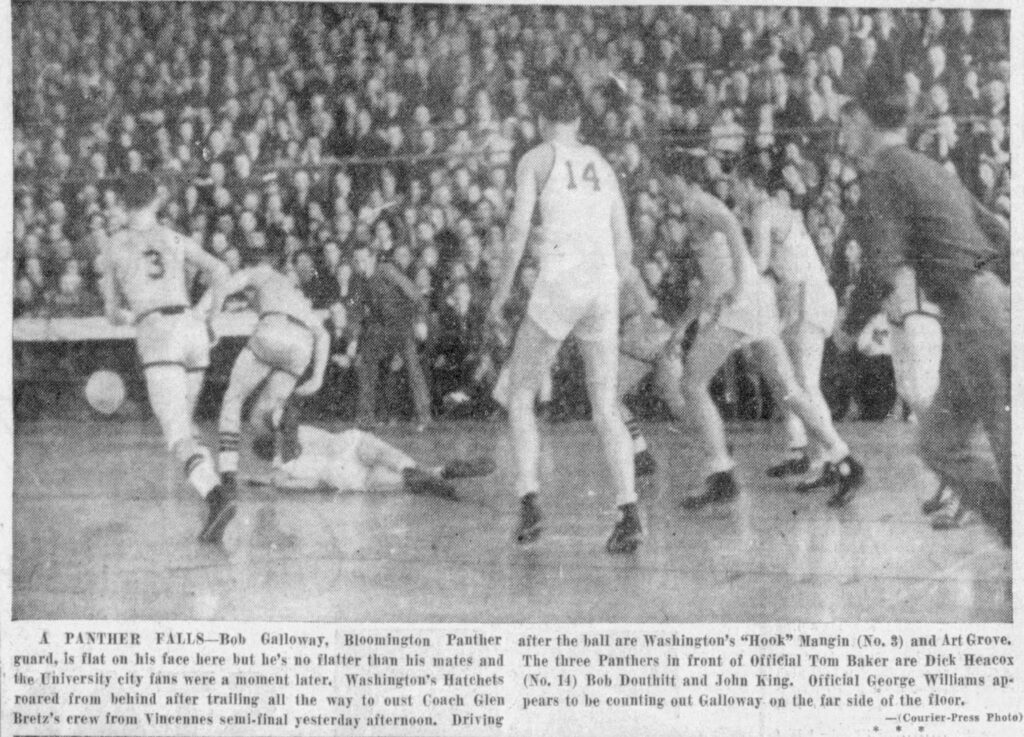

The Washington Hatchets were no strangers to Indiana high school basketball success, but starting the 1939-1940 season, their next few years looked to be fantastic— a possible state championship three-peat squad. In early 1940, they had a seventeen-game winning streak going into the final game of the semi-state tourney at Vincennes. A win would propel them to the final four level in Indianapolis and establish them as the favored team. The only other school that had looked the least bit dangerous was Bloomington, and the Hatchets disposed of them handily in the morning semi-state session of play. Then the lowly Mitchell Bluejackets upset the Hatchets 20-19 in the final contest, a Bluejacket making a free throw with just a few seconds left in the game. Mitchell went on to state and ended up with the second-place trophy.

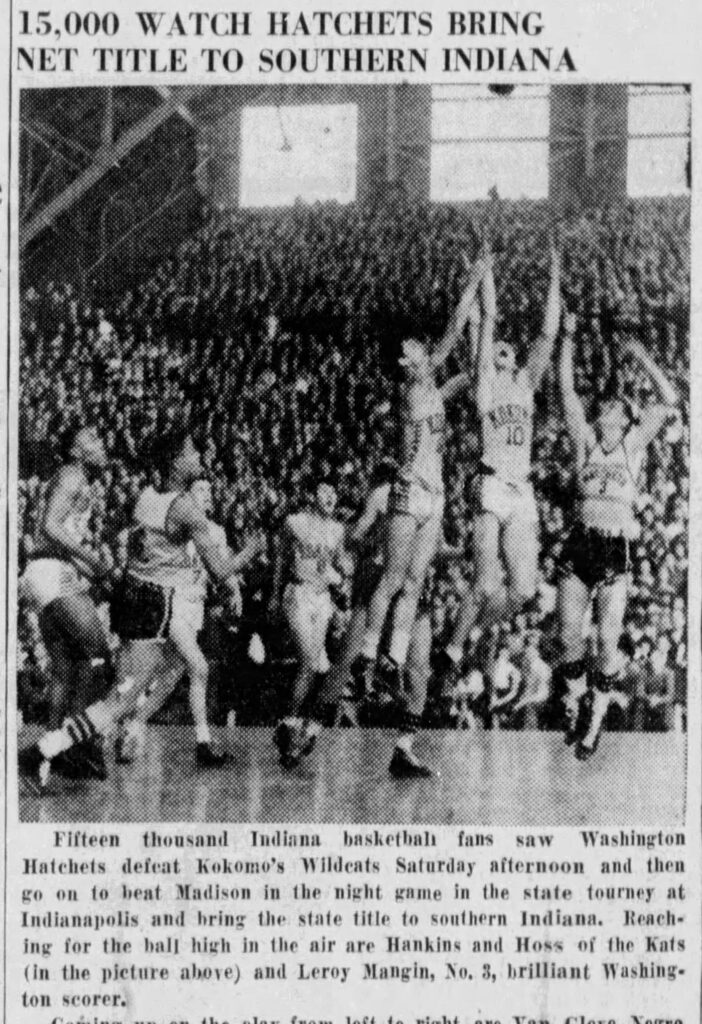

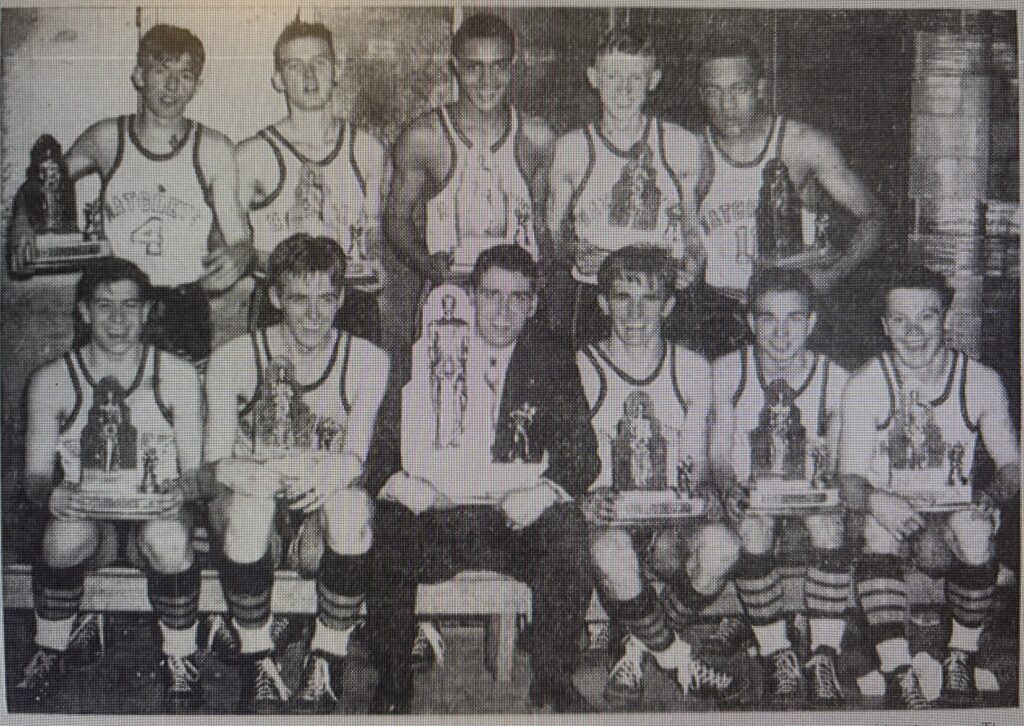

The next season, 1940-1941, was all glory. Washington roared into the final four tournament at the Butler Fieldhouse in Indianapolis and played what Butler College coach Tony Hinkle described as perfectly crafted Indiana high school basketball, the best in the nation— a sophisticated mixture of the famous Hoosier “fast play” and, when needed, a slower, deliberate pace. But Hoosier fans also loved flash, and national sportswriter Bill Brown wrote of the Hatchets also exhibiting true “Hoosier ball. No one was greedy about shooting. When they got into a tight spot, Washington restored to a fast break and the fast break won the championship.”

The Journal and Courier sports page in Lafayette labeled the Hatchets as the best state champs ever. “They can run and shoot with the best and their ball handling is first class.” To top off the circus-like atmosphere at the Indiana state tournament, Washington’s “most loyal rooter,” a ninety-three-year-old Civil War veteran, sat in the stands “as a good luck charm.” He had not missed a Hatchet game for seven years. As far as this research could find, there were no Civil War veterans cheering on an Illinois high school team.

The next year Washington cemented its place in Indiana High School basketball history, winning another state championship. The Hatchets lost only one game that season and the team’s machine-like effectiveness “was praised from here to yonder,” as touted by one Indiana sportswriter. “Champs rated among the state’s greatest five,” raved another paper.

But even after achieving back-to back championships, ending the 1941-1942 season at 30-1, and being acclaimed as one of the best Indiana state champ teams ever, many fans felt that the Indiana champions sat unfairly under the cloud of the Centralia, Illinois, team. The Illinoisans had been followed by almost every state’s sport pages in the nation. Nor did the end of the basketball season finish the unresolved situation.

Then the issue between who had the best high school basketball suddenly grew fiercer with the main instigator a former Hoosier high school basketball coach.

________________________________________

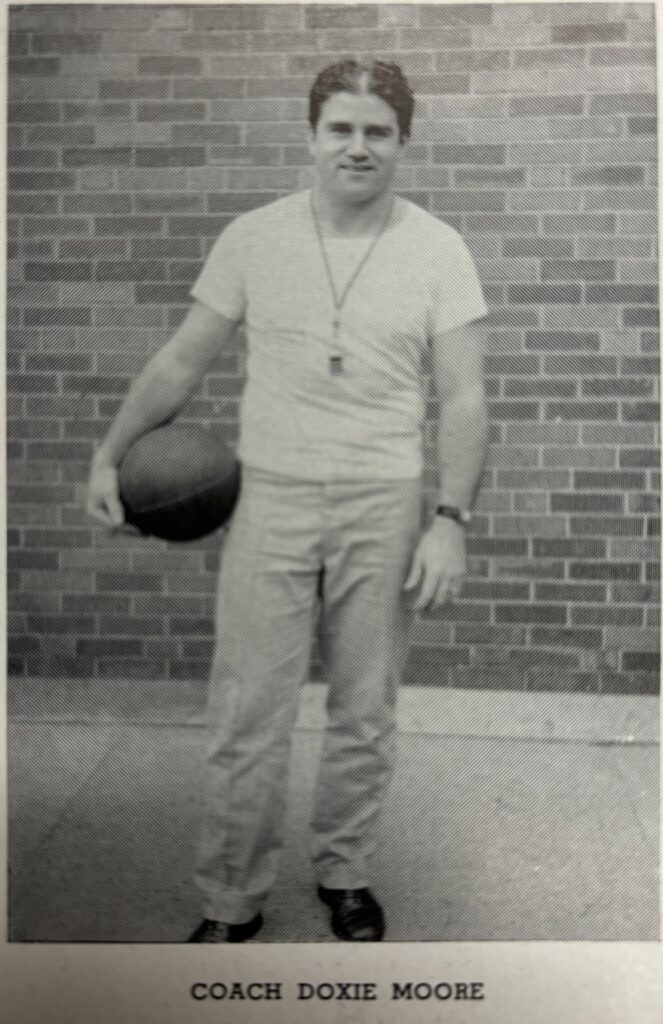

In the spring of 1938, Delphi, Indiana, native Doxie Moore left Hoosierdom to become the new high school athletic director and coach football and basketball at Mt. Vernon, Illinois. At the time Moore had been coaching successfully for several years at West Lafayette, Indiana.

Moore’s leaving was a shock, his resignation being announced in a sports headline in the Lafayette Journal and Courier. The local paper pondered why any Indiana coach would leave the high school basketball Mecca of the entire country to coach in another state. The region’s well-known sportswriter, Gordon Graham, who wrote a column under the byline “Graham Crackers,” also noted Moore had been a local star basketball player at Delphi High School, “building up a reputation as one of Indiana’s finest floor guards.” After high school, Doxie had gone on to Purdue. He started on both the school’s football and basketball teams where he played alongside John Wooden in the latter sport.

In his final analysis of Moore’s leaving Indiana for Illinois, Graham explained, “The Mt. Vernon, Ill. job is probably more of an advancement than most followers realize. Among other things it means a 40 percent increase in salary. Also, Doxie will have everything to work with, in the way of equipment and playing facilities.” The latter included, “a brand-new gymnasium, a well-lighted football field. Such things will be new to Coach Moore, who spent considerable time here trying to find some place for the Red Devils to practice.”

While Centralia’s Coach Trout was eccentric, Doxie Moore was a bit of a trickster who got results, and it is not surprising that his first basketball assignment in Illinois started on a strong note. His boys just missed going to the 1939 state finals, losing to Centralia 23-17. The next year Mt. Vernon made it to the sectional level but lost in the early rounds. In 1941, the scrappy Rams made it to the finals of the regional again, one game from state tournament play, losing to Centralia’s Wonder Five. But the best was yet to come. The next year Doxie’s squad finished the regular season with 18 wins and three losses and just missed taking the conference championship “by a whisker.” Mt. Vernon also had two wins over Centralia in the regular season, and Moore’s team was considered “a serious threat in the coming state tournament.” Before they were finally knocked out of tourney play, they were 29-4.

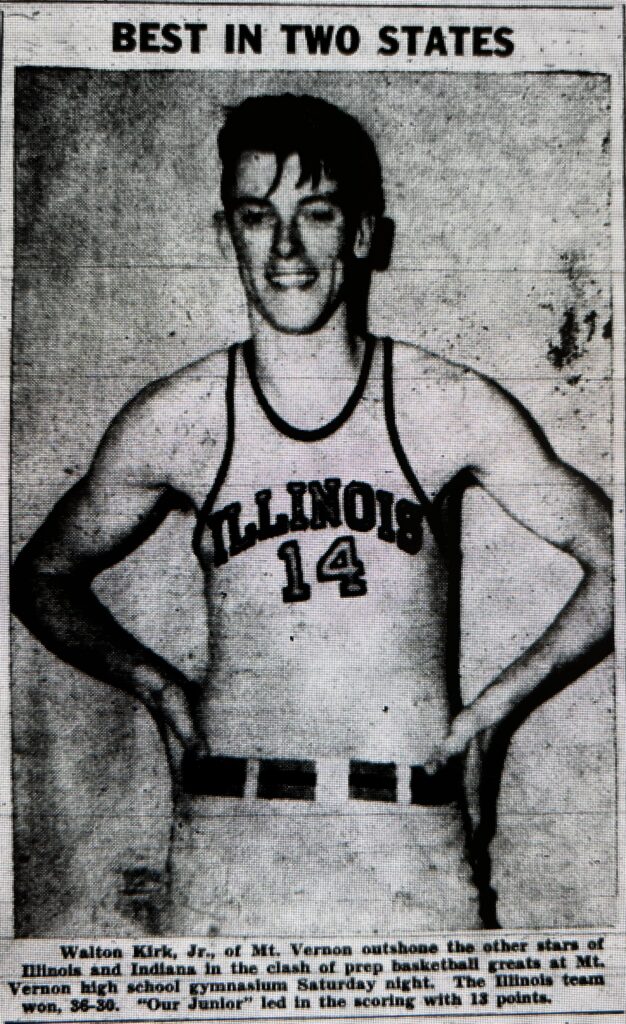

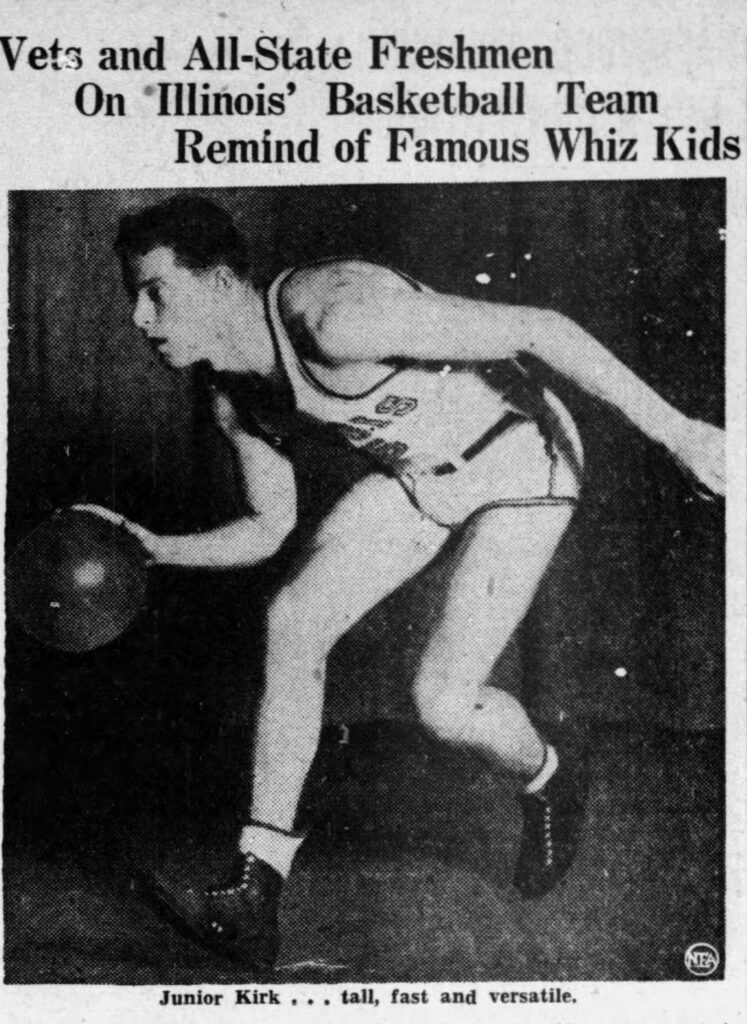

Prominent among the Mt. Vernon players in 1942 was Junior Kirk, a senior many thought was as good a basketball player as Dike Eddelman. Doxie’s troops however, lost a heartbreaker against Centralia in the championship regional game, just missing out on going to state sweet-sixteen finals. Kirk had the ball and Mt. Vernon was up by two with seconds left when a Centralia guard stole the ball, dribbled down court, scored, and was fouled.

Centralia went on to win the state tourney.

Two weeks after Mt. Vernon’s stinging loss and after Centralia won an all-but impossible victory in the last seconds to win the state crown, Doxie Moore visited his old basketball stomping grounds in West Lafayette, Indiana. He dropped by the newspaper office of Gordon Graham, Mr. “Graham Cracker” himself. And in that meeting, a seed was planted.

______________________________

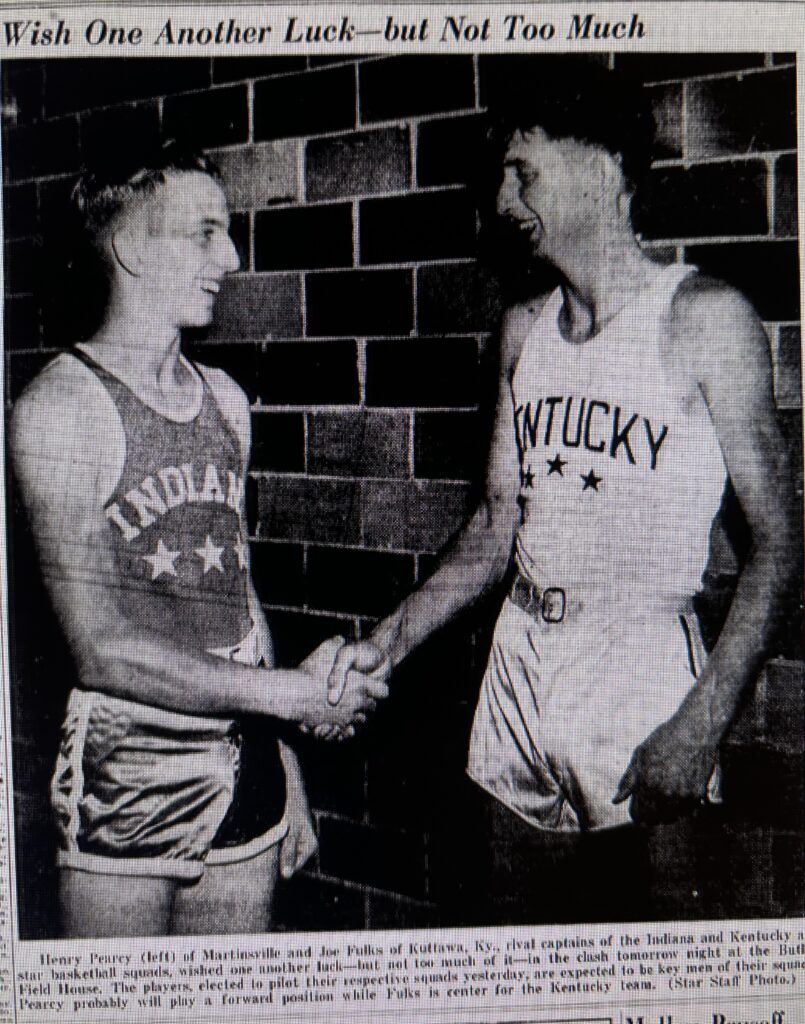

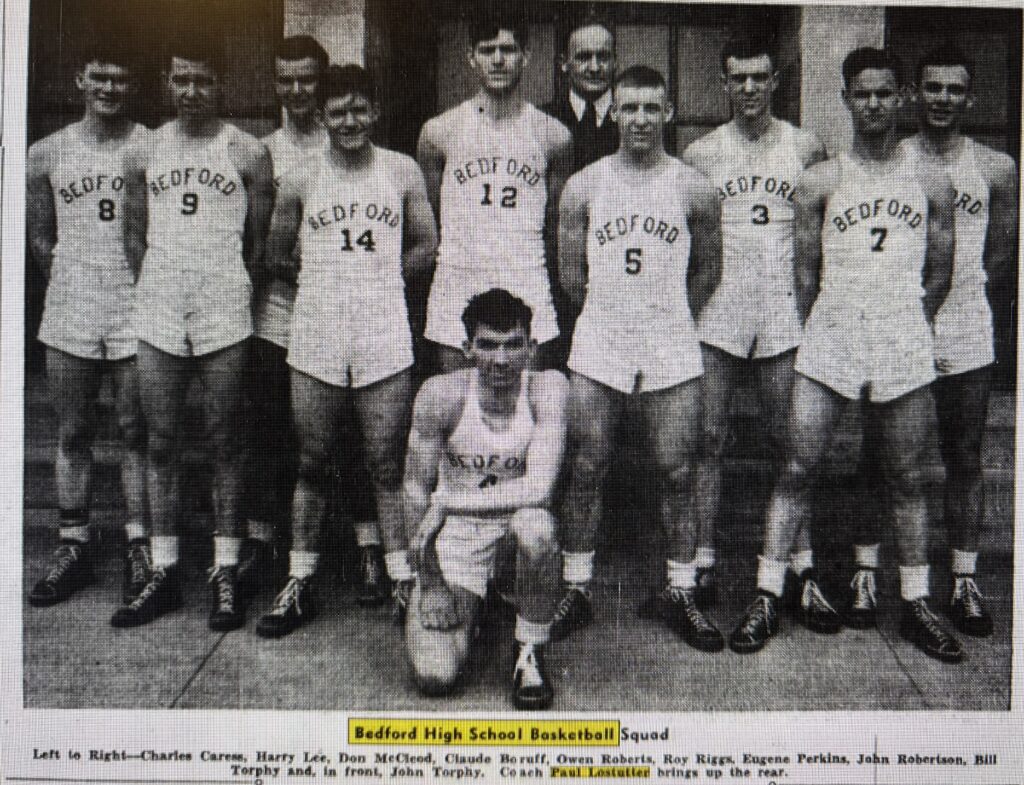

Graham was surprised when Doxie Moore spoke up for Illinois high school basketball in general, saying it was as good as Indiana’s, if not better, in terms of specific teams. As noted, Indiana and Kentucky had begun having a yearly all-star game in 1940 to settle the same issue, so it was only natural that the idea of an Illinois/Indiana all-star game popped up in the two men’s conversation. Doxie’s Indiana high school basketball coach, Paul Lostutter, happened to be directing the Indiana All-stars against Kentucky in 1942. Lostutter had been Doxie’s coaching rival when Moore was at the helm of West Lafayette.

Moore got in touch with his former mentor, and a game between Illinois and Indiana high school players was soon agreed upon.

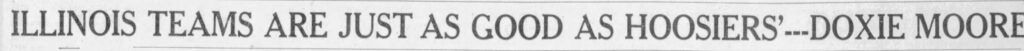

Moore was as good of a promoter as he was a coach. He let Indiana sportswriters know about the big contest, giving them a quote that appeared across the state in many newspapers—“Illinois teams are just as good as Hoosiers—Doxie Moore.”

Blood in the water.

Paul Lostutter quickly responded that he had not lost a game as a rival coach to Moore back in Indiana and that he “was not planning to start now.” Soon it seemed as if everyone was jumping into the fight. Bob Ray, sports editor for the Bedford, Indiana, Daily Times-Mail, had the most to say on the subject, sending a withering blast Illinois fans’ way. Among other strong comments, he declared, “Illinois is stepping on our toes when they get the idea that they are the dominators of the sport known as basketball. Yes— basketball is gaining more interest in other states, but the interest shown and the class of competition can never be tougher or more interesting than Indiana basketball!!!”

Illinois sportswriters hotly disagreed, some arguing the two states were on equal terms, while others declaring Illinois teams were better. Arthur Trout, the Centralia coach, declared his team “could beat the best in Indiana easier than the best in Illinois.” Another Illinois newspaper report claimed his state was now the “nation’s basketball capital.”

In response, an Indiana newspaper promised that the Hoosier team coming to Mt. Vernon would show cocky Illinois fans “that Indiana was the home and the only hot bed of hardwood sports.” Another Hoosier sportswriter, writing about the upcoming battle, explained that the Indiana playing style was “faster and craftier” than what Illinois teams played and would make the difference regarding who would win.

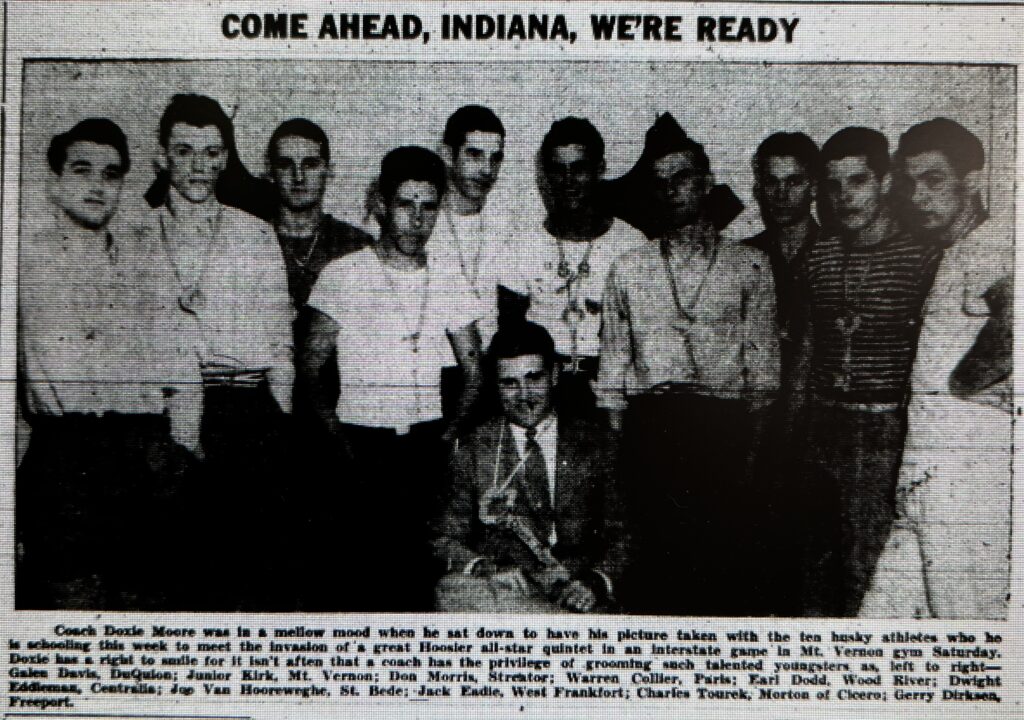

Doxie Moore just rubbed his hands in anticipation as both sides put together their teams. A week before the battle, Illinois papers began referring to the upcoming battle as the “Dream Game.”

________________________________________

It might have seemed Indiana’s Coach Lostutter held an advantage, having already put together and worked for two weeks with an Indiana All-Star team to play Kentucky. Unfortunately, the Hoosier squad played the Kentucky team the night before the Illinois contest, and although they beat the players from the blue grass state 41-40, the Indiana boys were wrung out for the next day’s play in Illinois. Lostutter, however, had anticipated the situation. He created a different team, taking his two best members from the initial All-Star squad, Charlie Harmon and John DeJarnett, who had been a part of the Washington High School state championship team, along with the rest of the Washington players and three top Evansville Central players to go up against Doxie Moore’s squad in the Mt. Vernon, Illinois, match. The Hoosier coach figured the Washington group would have a big advantage, having played together so successfully for at least two years. Meanwhile, since Lostutter had been Moore’s high school coach, Indiana newspapers framed the contest as “master against pupil.”

Doxie Moore now had to put his money where his mouth was. He carefully picked his Illinois crew from the best in the state. Settling quickly on Dike Eddelman and his own player, Junior Kirk, he added Jack Eadie from a great West Frankfort team, Warren Collier from state runner-up Paris, Don Morris of Streator, Gale Davis from Duquoin, Earl Dodds from Wood River, and four other players. He also announced to sports reporters that he would drill his team “to recognize the opposition’s weakness on the floor and hit them hard,” whatever that meant.

The day before the big tilt, Moore finally revealed some doubt, telling an Indiana reporter, “We probably won’t look very smooth against Indiana because we haven’t played together as long, but we’re going to make an honest effort to win.” Moore also emphasized another Indiana advantage. “We must work hard to become a smooth clicking team against a group of Indiana boys who have already been practicing for two weeks.” A Bedford, Indiana, sportswriter tried to get in the last word, declaring the Indiana team, after beating the Kentucky crew, “took off for Mt. Vernon to give ‘cocky’ Illinois fans a dose of the same medicine.”

_______________________________________

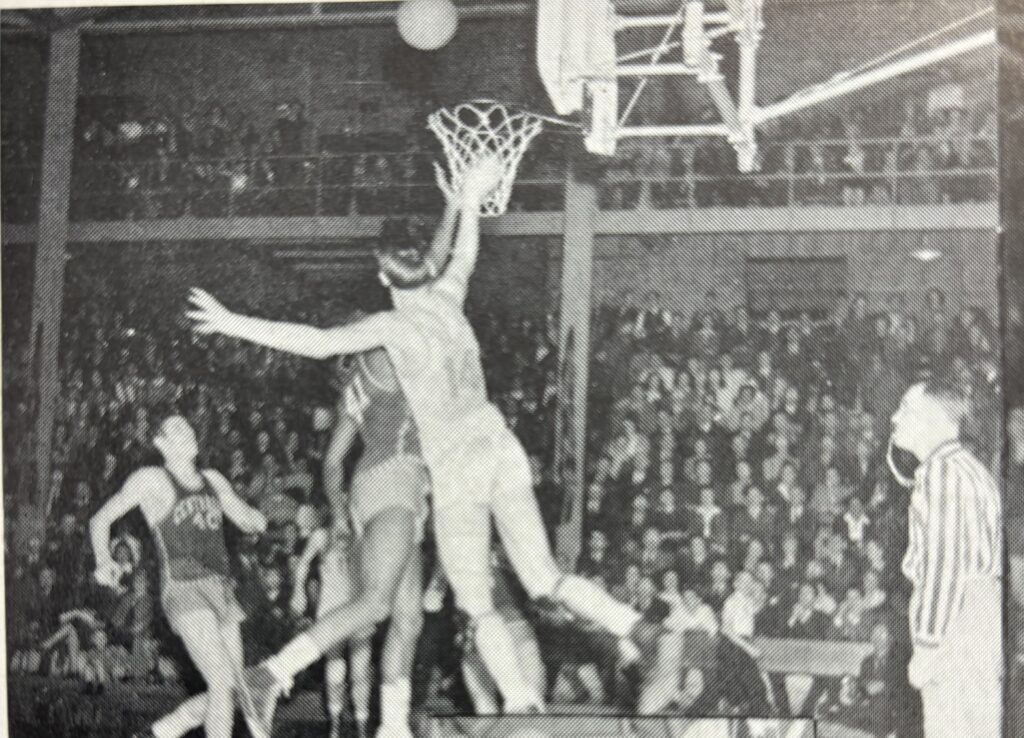

It was late August of 1942 and the temperature was “torrid” in the Mt. Vernon gym when the Illinois and Indiana teams took the floor. Political dignitaries, college coaches, and regional and national sports reporters sat interspersed among the sweating, crushing crowd. Among the dignitaries was Coach Trout, somehow managing to look cool and calm in the heat.

The Illinois fans were stunned to silence in the first several minutes of the game. An Indiana paper observed that “a tight man-to-man defense and the brilliant shooting of Charlie Harmon and John DeJarnett from Washington, pushed the Hoosier ahead 19-3.” It was a horrifying situation for the Illinois fans, leading an Illinois reporter to write how “Illinois supporters settled back to watch their favorites absorb what appeared to be a terrific licking.”

Coach Losutter’s game plan of bringing the entire starting five of the Washington Hatchett high school team was working. At halftime, Indiana was up by nine, 22-13 and the fans, mostly Illinois supporters, were still drowsy in their seats, suffering in the sweltering heat. Dike Eddelman did not help his team’s efforts. He missed most of his shots, ending up 2-17 from the field and missing over half his free throws during the contest.

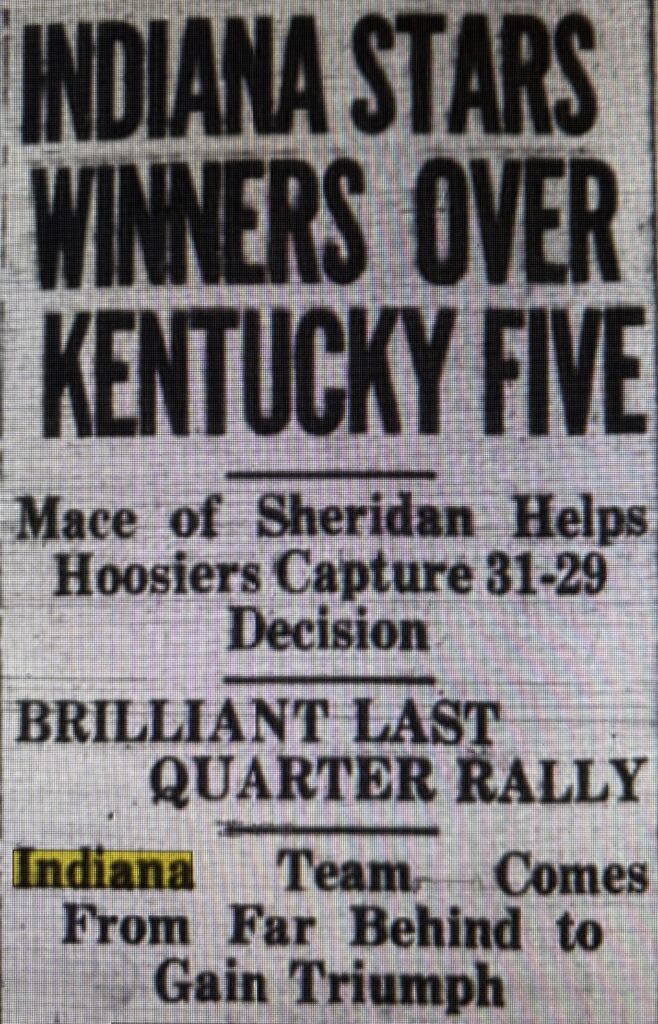

Junior Kirk, playing in the confines of his home court before hundreds of his old fans, and Streator, Illinois’s Don Morris got hot in the third quarter, the Illinois team creeping up on the Hoosier squad, behind by three thin points at the end of three quarters.

The last quarter was a game in itself. Kirk scored for Illinois in the first minute and was fouled. He made the foul shot, tying the game. No one was snoozing now.

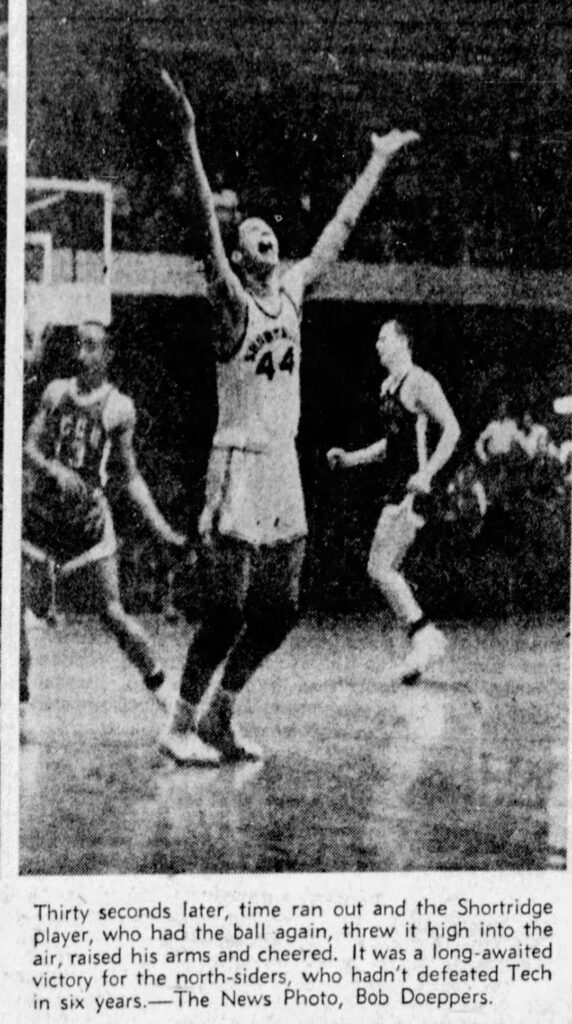

Jim Riffey, All-Star Indiana center from Washington, hit a basket that put the Hosier squad back in the lead before Eddelman rebounded and scored. DeJarnett then got the lead back for Indiana. Jim Riffey did some damage against the Illinois team but Indiana’s efforts no longer mattered. Kirk hit three more shots and the Illinois defense shut out Indiana, giving the Illinois All-Stars a stunning 36-30 victory.

The next day Gordon Graham placed a sports headline in the Lafayette, Indiana, Journal Courier declaring, “Doxie Moore Wins Great Victory in Illinois Triumph” and noted that the Indiana team discovered “they play good basketball in Illinois too.” An Evansville Press writer observed that “the name of Junior Kirk was on every tongue as 2300 fans filed out of the torrid Mt. Vernon gymnasium.” The reporter also believed that Dike Eddelman’s key role as the “ball controller” and his scoring of a key basket that finally put his team in the lead were also two essential elements of the victory.

Most Indiana newspapers carried only short pieces about the disappointing loss. A few pointed out that the so-called Indiana all-star team that played at Mt. Vernon, Illinois, was not really a full state team, but rather a southern Indiana team. George Schunk, sportswriter at the Freeport, Illinois, Journal-Standard argued otherwise. “Victory for the Illinois All-Stars over Indiana’s best by a 36-30 margin at Mt. Vernon last Saturday night provided, in our mind at least, complete vindication for the type of basketball played in this state over the Hoosier brand.” Schunck also noted that Indiana’s Coach Lostutter “was quick to admit” that the team that came to Illinois “was a better team than the Indiana All-Stars who nosed out a Kentucky team.” The writer then asserted, “We’ve always contended that most years the Illinois champion and Indiana champion would stack up about even but that if the first teams in each state were matched, the verdict would favor Illinois.” And that seemed to be that, at least for a while.

__________________________________________

The ramping up of World War II dampened many all-star games in the short run and the two states never played each other again in an all-star setting. Those involved directly and indirectly in the dream game went their own ways, fading into one form or the other of obscurity. Dwight Eddelman, “the greatest Illinois athlete of the 20th century,” and Junior Kirk both enrolled at the University of Illinois, their careers impacted by military service. Both would play professional basketball for a few years. Washington, Indiana’s, big Jim Riffey would also play pro ball after graduating from Tulane.

Coach Trout would work for thirty-seven years coaching at Centralia High School, retiring in 1951 after gaining 809 victories, having ten state tournament teams, and winning three state championships. He would be the winningest coach in the state and nation for several years. His most famous innovation, the two-handed “Centralia kiss-shot” lived only during his coaching career and a few years after, soon as dead and as strange as a dinosaur fossil.

Paul Lostutter, after a coaching career at Delphi and Bedford Indiana high schools, became a sportswriter in the fall of 1942 at the Bedford newspaper and then ran for mayor of the city and won, finding politics more to his liking.

Doxie Moore, a restless soul, joined the Navy Reserve in 1943, and after the war got involved in the National Basketball League and then in the NBA. His feistiest moment occurred when he knocked down Celtics coach Red Auerbach in 1952 while coaching the Milwaukee Hawks. On the Milwaukee team that same year were Dike Eddelman and Junior Kirk. Later, Moore would come back home to Indiana and serve on the first five-man board of the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame.

So why didn’t Illinois high school basketball stay on top, if, in fact, they had actually achieved that status by winning the showdown in 1942? At the start of the 1950s, Illinois did indeed seem to have the upper hand when it came to high school basketball. Mt. Vernon, Illinois, had back-to-back state champion teams, going undefeated in the 1949-1950 season. The 1950 team was considered the best high school basketball team in the state for several years, and some argued, the best in the nation. Mt. Vernon also took third place in 1952 and won another state championship in 1954. Premier southern Illinois sportswriter Merle Jones wrote that Mt. Vernon had the best “system” of high school basketball training and performing he had ever seen. This included having a coaching staff that was the first to teach every player how to shoot a fairly modern version of the jump shot.

Meanwhile, in 1952, tiny Hebron High School, with a total of 98 students, came out of the lowly district tournament level to win an Illinois state basketball championship, giving the state a basketball legend that should have gained national attention. Instead, Indiana’s Milan High School, a school a bit larger than Hebron, became the archetypical tale of small school success in 1954, one that ended up THE national basketball legend of small town hopes, a story made into a national myth in 1985 by the movie about a fictitious Indiana small-town school, Hickory, that miraculously wins a state tournament by besting a much larger school. Today, few folks in Illinois remember Dwight Eddelman, Junior Kirk, or the “Dream Game,” but even many non-Hoosiers can tell you what Milan’s Bobby Plump accomplished, dribbling at the top of the key in Butler Fieldhouse with eighteen seconds left and the score tied before he would make that last move toward the basket. Of course, the play of Oscar Robertson, Larry Bird, and Damon Bailey, and Bob Knight’s great run in the mid 1970s, at IU certainly didn’t hurt Indiana fans’ argument.