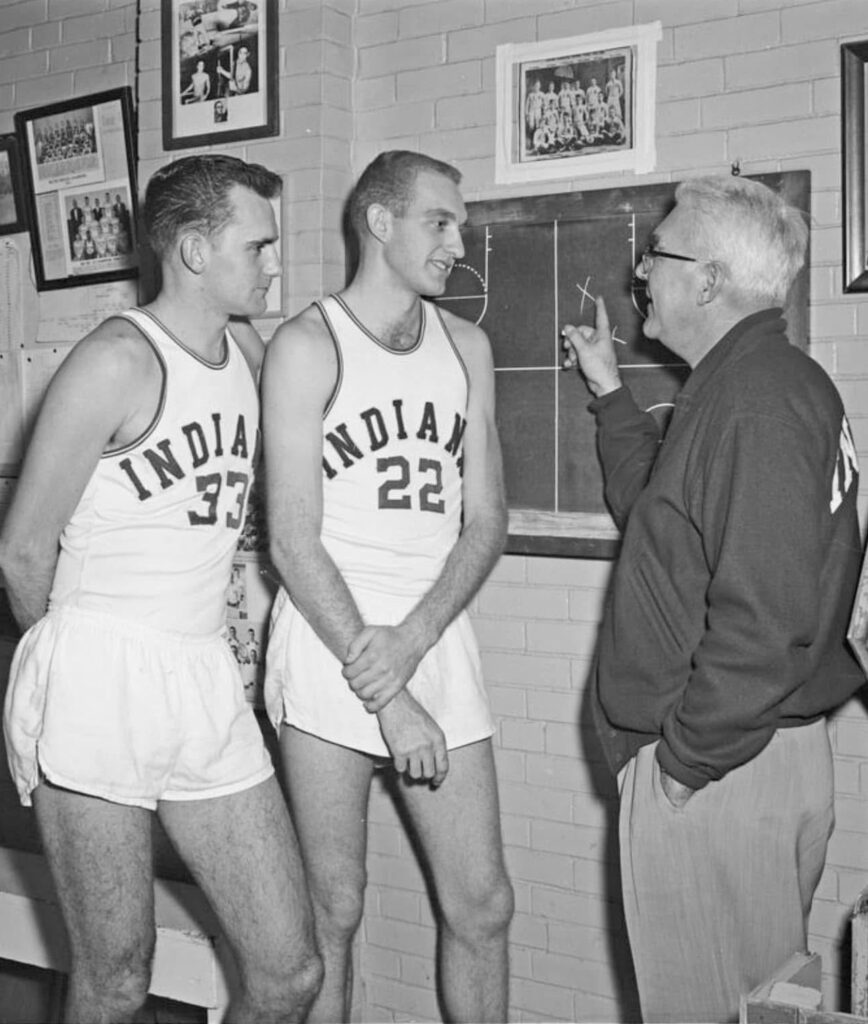

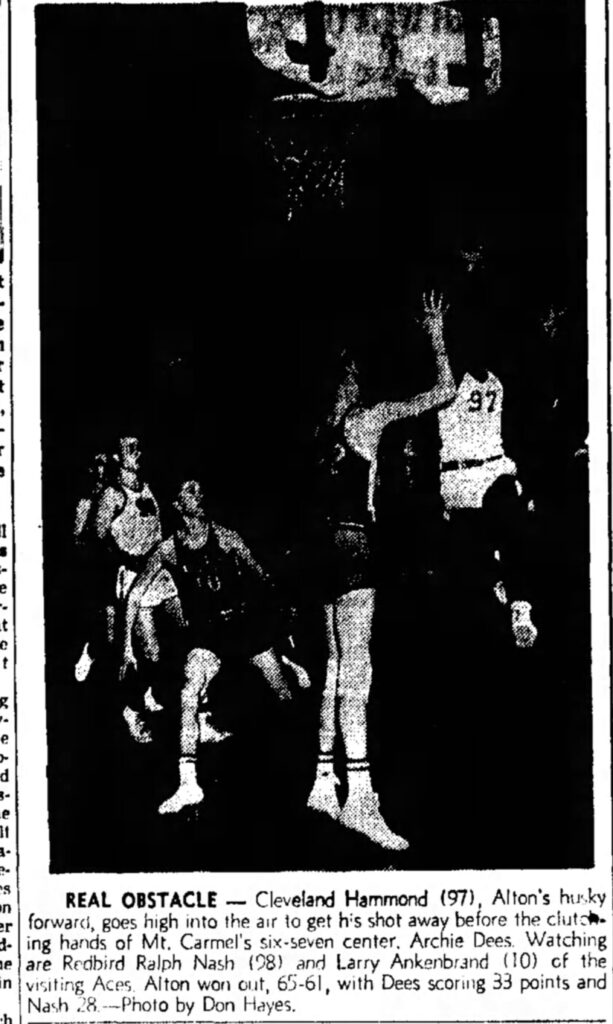

Mostly forgotten today, southern Illinois’ Archie Dees was one of the most highly sought after high school basketball players in the country. It’s easy to see why college coaches like Indiana’s Branch McCracken so badly wanted the young man to play basketball at their place, and would stoop to almost anything to get the job done. After Archie’s senior high school year of leading the state in scoring at Mt. Carmel, Illinois, Dees was chosen as the nation’s high school “Mr. Basketball.” But even before that final accolade, Dees had been bombarded with offers to play basketball at universities all across the nation.

(Southern Illinoisan, 1954)

There were always rumors flying around that Dees would definitely attend Illinois. Another line of gossip, however, had him locked in at Northwestern. Kentucky and Louisville were also mentioned by those in the know, one sports reporter claiming that the University of Louisville was going to give Dees a nice bonus of $150.00, certainly a temptation for Dees whose father worked hard at a low paying job in the oil fields of southern Illinois. Perhaps the most interesting claim came from a Kentucky sports reporter. “I understand that Archie Dees, called the greatest high school player in the country, is headed to Evansville (College). The Mt. Carmel giant’s girl friend attends college there and that could be the deciding factor. Also, a millionaire friend of Archie’s wants him to attend the school.”

By halfway through the 1953-1954 season, most sportswriters agreed Dees was definitely headed to the University of Illinois. Then in mid-March, out of nowhere, a new contender emerged. Merle Jones, sports editor at the Southern Illinoisan reported, “University of Illinois talent scouts are hereby warned they must get busy if they want Archie Dees, the 6-8 Mt. Carmel senior. Very good sources from both Mt. Carmel and Indiana University have recently told me that Dees at the moment is all wrapped up for delivery to Indiana.” And thus was it so. Like the biblical thief in the night, Branch McCracken had come and gotten his man and taken him to Bloomington, Indiana.

(Chicago Tribune, 1954)

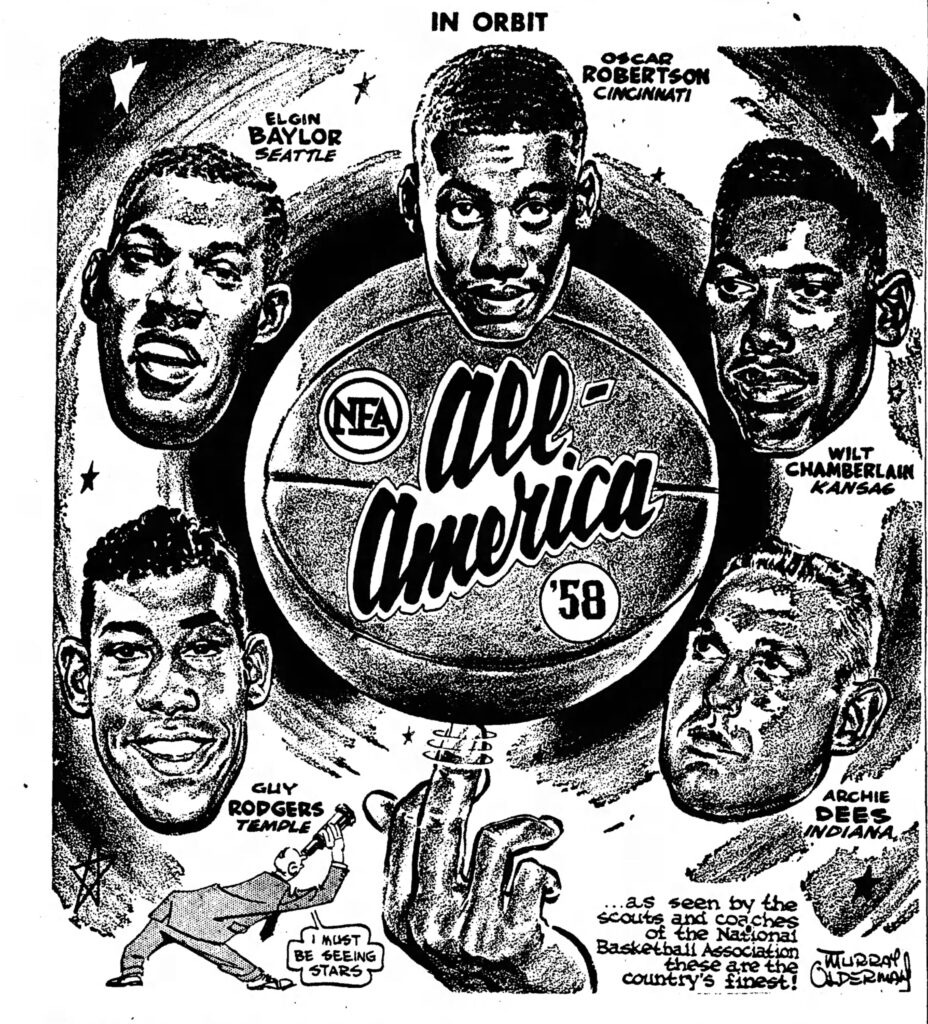

It was a great deal for Dees, Coach McCracken, and IU. Dees would end up as one of the top five players in the nation his college senior year, according to one All-American basketball team poll, along with Wilt Chamberlain, Oscar Roberson, Elgin Baylor, and Guy Rogers. Dees was also the Big Ten’s most valuable player his last two year at Indiana University, leading the league in scoring both years and driving IU to back-to-back conference championships. NBA play with the Cincinnati Royals and with Oscar Robertson followed.

(From the Mt. Vernon (Illinois) Register News,1958)

But for all their love and admiration of Archie Dees, few Hoosier fans probably knew of their hero’s triumphs and sorrows before he came to Indiana, of Dees’ occasional difficult times playing high school basketball in southern Illinois, and how my dad, Keith Mills, came to be standing by Archie at the very moment of Dees’ greatest disappointment, the game Arch always wished he could do over. Here is that story.

(Indiana Basketball Memories)

__________________________________

The drafty southern Illinois farmhouse where I grew to young manhood has been gone for decades, along with our one car garage crowned with corrugated tin that stood nearby. Gone too is the crude basketball court where I first labored to learn the basic skills of the round ball game. In truth, the court was more of an idea than a solid reality. Its dimensions were small, its boundaries, sketchy. Still, it was the Troy of my basketball odyssey. And like any story of a journey, it involved the hopes and struggles of the would-be hero.

It was shortly after I played my first peewee basketball game at little Farrington Grade School in the early 1960s that my father, Keith Mills, with the help of Grandpa Mills, put up a crude backboard and goal on the front portion of our one car garage. Grandpa, a farmer, kept a noncommittal posture the entire time he worked, his face as inscrutable as a sullen Buddha’s. My job was handing the hammer, level, or whatever to whoever stood up on the ladder while the other adult on the ground eyed the work from different angles, offering verbal corrections regarding key placements—“A little higher” “Maybe move it a bit to the right.”

As the crowning finish to the project, I got to hang the white, yet to be soiled net. Grandpa Mills began picking up his scattered tools, ready to get back to farming.

There were severe limitations to the new court. Given the shortness of the front of the garage, the goal had to be set a few inches below the regulation ten feet. And the playing area was uneven in spots with different depths of gravel spread over much of it. Hit a big piece of gravel the wrong way while dribbling and the basketball took off with a life of its own. One last issue, an infrequent one, involved my dad parking the car he drove to work smack in the middle of the tiny court. Asking him to move it on a weekend or after work could be dicey, depending on his mood.

Memories of playing with my dad those first few years on the gravelly court are fuzzy, trapped in memory’s amber hue. Dad did explain how he went to tiny two-year Shields high school, called Papertown by locals, playing for the Papertown Tigers. This would have been in the early 1940s, on the cusp of World War Two. Tiger victories were few and far between, and Dad finished his last two years of high school at big-city Mt. Vernon, where he could only fantasize about playing basketball for the storied Rams.

Playing on the court was the first time Dad and I spent focused time together, his tales of basketball coming from so many different times, places, and angles they often converged, ghosts hovering at the periphery, demanding attention. There still lingers in my mind one particular image from dad’s chatter, a basketball captured by a stiff wind at an outdoors Shields basketball game and carried deep into a nearby field of weeds, never to be found.

There was one memorable shoot around with my dad at the home-made court, perhaps our last. The contest took place in late spring at the end of my eighth-grade year. It was sultry, without a touch of a breeze. At the start, between baskets, in a rough toe-to-toe battle, we talked about my chances of playing varsity basketball at Bluford High School. Dad spoke with great encouragement regarding my possible high school career, lofting a couple of two-handed push shots that hit the back of the rim and bounced in.The pace quickened.

Soon Dad was huffing like an exhausted train engine going up a steep grade. He had no extra breath to waste on talking.

I showed no mercy until the end, when I suddenly became aware of the surprised and confused looks on his face as I scored easily and blocked his two-handed push shots back into his face. I felt an unexpected jolt of guilt and shame when he raised a hand and managed to croak out, “enough!”

He staggered away to the edge of the court, red-faced, gasping for air. I said the first thing that came to my mind, something I hoped would reset the moment— “Dad, what the most unforgettable high school basketball game you ever saw?”

There was a trace of a smile, a few seconds of an inward glance, like the sudden thought of a forgotten lover.

________________________________________

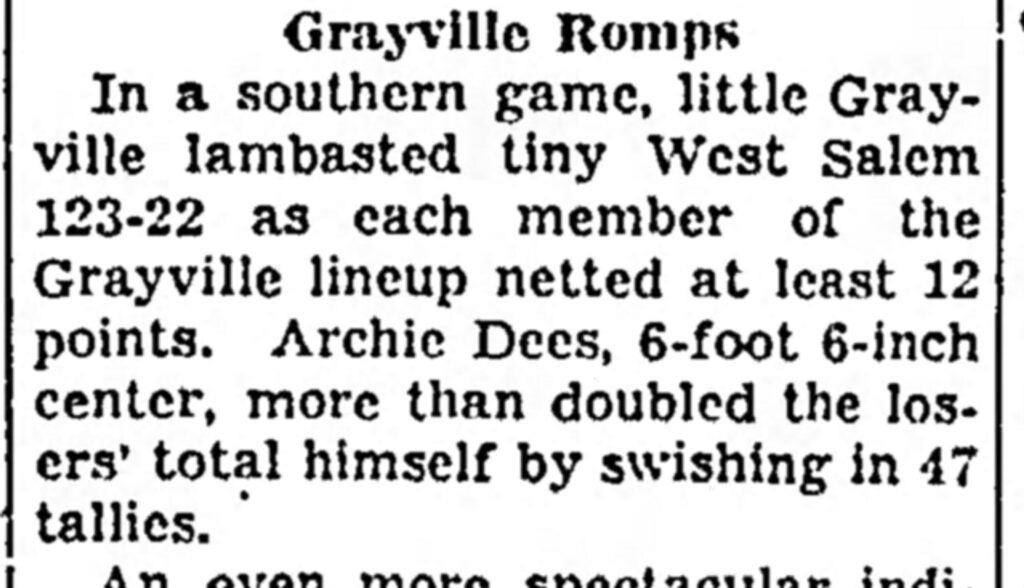

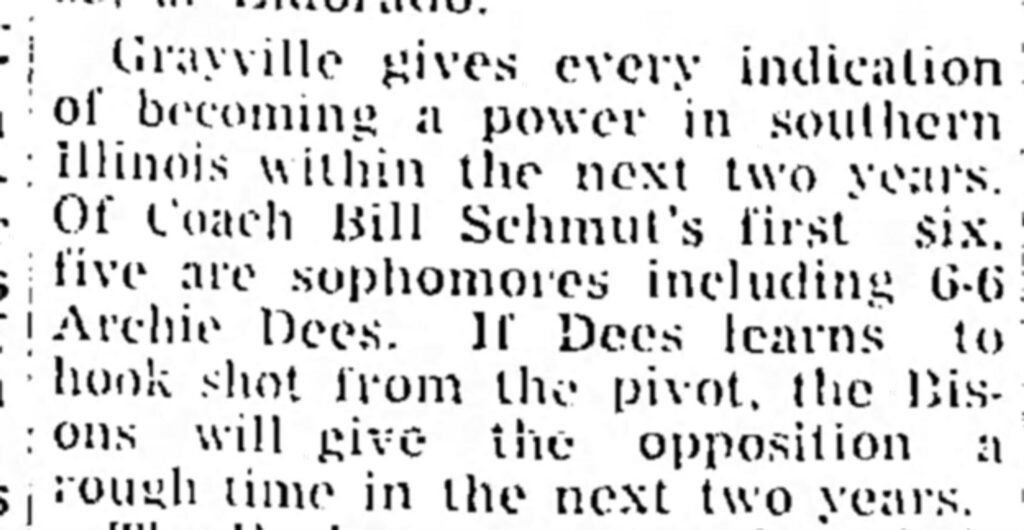

Excitement was a rare commodity in the southern Illinois village of Grayville, nestled on the west bank of the Wabash River. The town’s high school basketball team, the Bisons, were about to change all of that. By late in the 1951-1952 campaign they had lost only one game and were picked to win the Little Ten Conference. Somewhere in this march to basketball glory, Grayville crushed West Salem 123-22, with a lanky 6-5 sophomore center named Archie Dees scoring 47 points, a scoring feat which appeared in almost every Illinois newspapers’ sports page. Dees was great on defense too. “The key to Grayville success,” observed one sports reporter, “is a stiff defense revolving around Archie Dees, 6-5 center, whom his mates call the ‘iron curtain.”’

Perhaps the best news of all was that the team had a solid core of sophomores who could only grow better over the next two years.

At the end of the regular season, the Grayville Bison team held a 20-3 record, “the best team in its history,” noted a sports headline. The article added that Archie Dees had grown to almost 6-7, and was one of the better players in the region. Many Bison fans, and several sportswriters, believed the Grayville team would beat district champ Bluford, a small-town team that had a 23-5 record, and big school Fairfield in the first two rounds of regional action and then meet powerhouse Mt. Vernon in the regional finals.

The first part came true. Grayville got by Bluford, the school I played for in the late 1960s. The Bisons, however, lost to Fairfield 52-48 in a semi-final game. Mt. Vernon would win the regional and take third place in the state that year. Still, Grayville fans were elated by the season, many cheering, “Wait until next year, and the next year.” Unknown to the Bison fans, however, one Grayville player carried a painful secret.

It probably did not help Archie Dees that his family were outsiders with little money who came from Mississippi to Grayville when Archie was twelve. His father found work in the Grayville area as a driller in the oil fields. But the biggest problem for Archie stemmed from his unusual growth spurt. Folks had difficulty adjusting to Dees’ amazing increase in height, treating him as something of an oddity. In the 1976 interview Archie gave the Evansville Courier, he explained, “I was very thin and awkward when I started high school. Then I grew from 5-8 the start of my freshman year to 6-6 at the end of my sophomore year, and the fast growth caused me trouble. Later in life you understand it, but at the time it hurts to be considered a freak.” Luckily, the tall lean youngster could play basketball, a valuable commodity in southern Illinois.

Grayville fans began talking about the future Bison team immediately after the squad had lost to Fairfield in the 1952 regional. It made their mouths water to think what the next two years would bring, maybe even a deep run in the single class state tournament. Even the skeptics thought the team could get beyond the regional level of state tournament play if Mt. Vernon was shifted to another regional site, which was the gossip, or, even give the Rams a run for their money if the two teams did meet early on.

Then came the rumors.

In late March of 1952, the Lawrence County News, in their sports column, “Split Tease,”dropped a bombshell on the southern Illinois basketball world. “The word has been circulating, unconfirmed of course, that Archie Dees is transferring from Grayville High School to Mt. Carmel. If the rumor is true, think what a powerhouse Coach Bob Mirus is going to have at Mt. Carmel next year.” As it turned out, there was nothing official forthcoming with this particular tale. Nevertheless, Grayville fans must have been sitting on the edge of their proverbial seats as more rumors popped up. In early June, the Lawrence County News offered a new speculation. “The rumor is ripe that Archie Dees, 6-6 center, will abandon Grayville for Fairfield. I heard the same dope about Dees and Mt. Carmel, too, and nothing jelled.”

Again, another dud rumor and another set of sighs of relief in Grayville.

Then came a real blow to the Grayville community and uplifting news for Mt. Carmel fans. In July, the Lawrence County New declared, “Look out, North Egypt Conference! After considerable investigation, I’ve learned that Archie Dees of Grayville is now working in Mt. Carmel and will enroll there next fall. Dees is the sky-scraping center who did so well for the Bisons last year and was the subject of numerous rumors involving transfer to Mt. Carmel or Fairfield. He has reputedly grown a little bit and supposed to be about 6-7. The Aces are looking forward to their finest cage team in many years.”

The Grayville community was devastated and enraged. Gone was the bright hope of having a once-in-a-lifetime high school basketball team, one that would be talked about through the ages.

There was a last-ditch effort to do something about the catastrophe. Grayville High School leaders lodged a complaint with the Illinois High School Association, accusing Mt. Carmel of “undue influence” in getting Dees to transfer, and asking that Mt. Carmel’s team be penalized and that Dees not be allowed to play. The IHSA ruling came in late October of 1952, with Archie’s transfer being allowed. Merle Jones at the Southern Illinoisan offered the guess that “Even though undue pressure was suspected, it could not be proven at a hearing.”

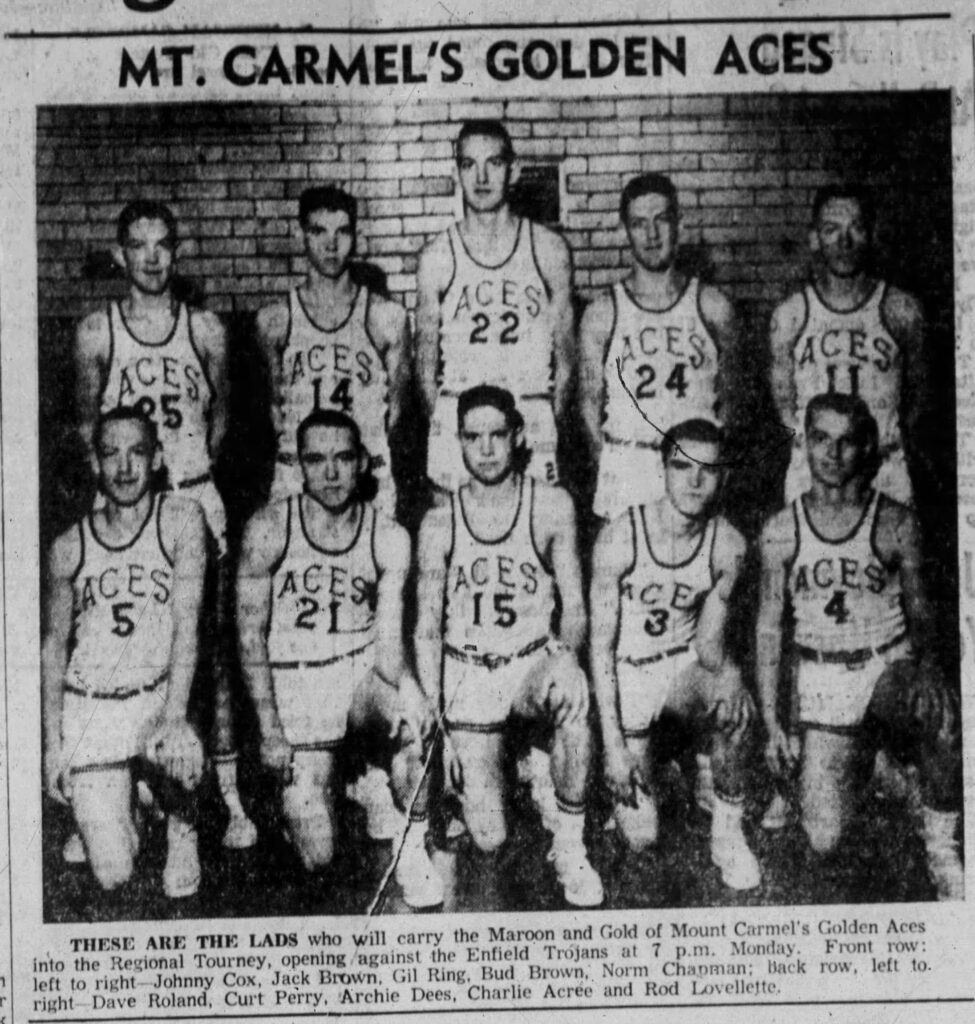

Archie Dees was now a part of the Golden Aces team.

Perhaps things were a bit better for Archie at Mt. Carmel, but there were still issues the teenager had to confront. “After we moved to Mt. Carmel, [Grayville] people made harassing telephone calls,” Dees remembered. “Sometimes they came by and threw things at the house— bricks, fruit, sticks. When we moved, I never dreamed it would be like that.” Archie had been close to the Grayville coach, Bill Schnute, and was glad to find out his old coach had nothing to do with some fans’ overheated reactions. Archie also later explained that his dad was out of work but was able to get another oil drilling job in Mt. Carmel. “People said I was paid to get us to move, but that’s not true. I didn’t get a thing.”

(Alton Evening Telegraph, 1953)

Archie also faced the new pressure of leading the Mt. Carmel team, one that he had not played with before. Expectations were sky-high and the competition would be much greater than the smaller schools he had played against when at Grayville. On top of that, powerful conference foe and arch rival Lawrenceville waited in the wings.

The season’s start was sweet, the Golden Aces playing like gangbusters, especially the lanky Dees. The Mt. Carmel community, long used to being a basketball doormat, came alive. After winning their first two games, one, a surprise victory over the powerful Centralia Orphans, they played Lawrenceville, losing by one point, 69-68. Lawrenceville would beat Dees and his fellow teammates once more in the regular season, but the Golden Aces went on to share the conference title with their arch rival and came into state tournament play at 18-6. Dees, for his part, often scored over 30 points in a game and had one of the highest scoring averages in the region and the state.

The shared conference title was Mt. Carmel’s first in sixteen years, and the town had gone wild over basketball, filling the gym with hungry fans. One sports writer claimed that “The advent of Dees’ transfer from Grayville to Mt. Carmel brought about the greatest restoration of basketball interest in Mt. Carmel ever known. With all his height and Dees’ uncanny shooting ability, the Aces practically overnight became one of Illinois’ strongest teams.” Golden Aces fans were happily talking about a sure run in the state tournament.

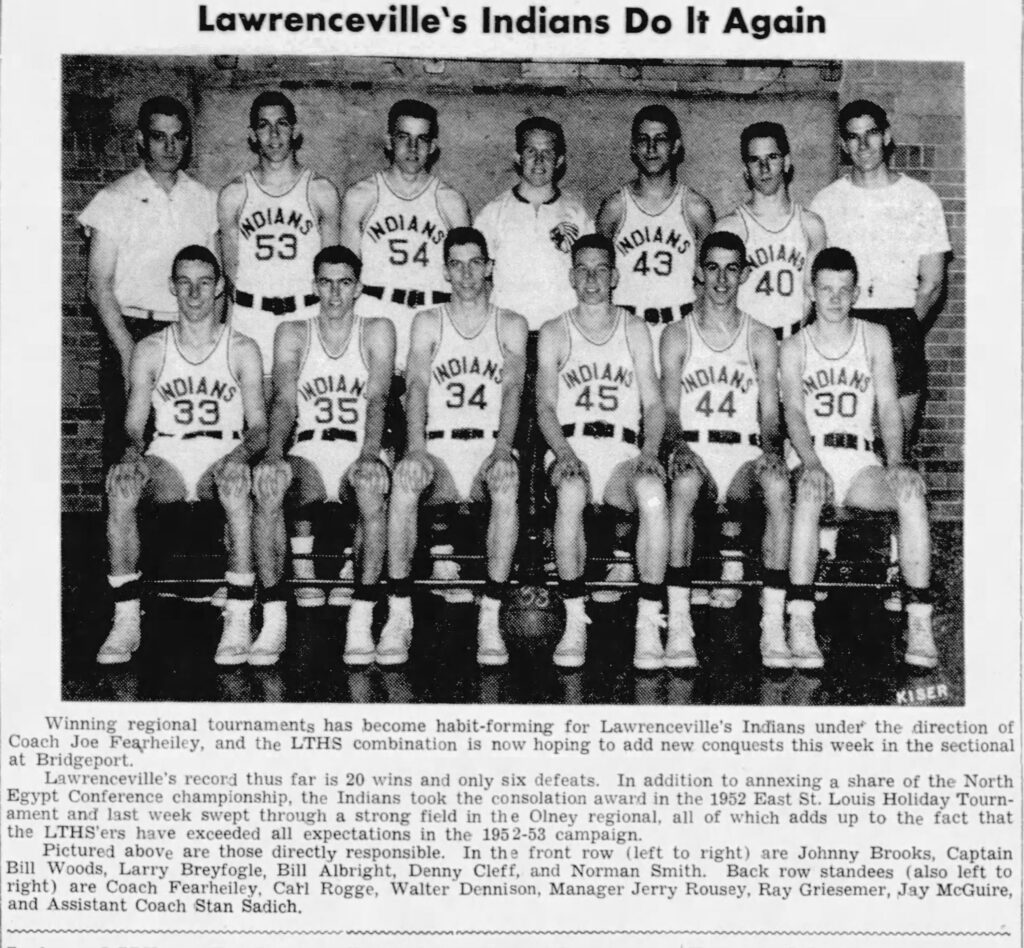

Someone should have told the Lawrenceville Indians.

(Lawrenceville County News, 1953)

The Golden Aces and the Indians met in a semi-final game of the Bridgeport sectional. In the final quarter, Archie tied the score twice. When the Indians went up by two with five minutes left, Mt. Carmel called a time out. In the hurdle, Coach Mirus told his team to foul. At that time, a player shot a single time when fouled until the last three minutes of the contest. Mirus hoped to trade one point for two and catch up. As one reporter noted, the plan backfired “thanks to the Mt. Carmel fouling procedure.” Archie Dees had 32 points in the loss. After beating Bridgeport in the championship, Lawrenceville would go on to the Sweet Sixteen state finals while Mt. Carmel went home.

High school basketball fans and high school officials in Illinois demanded a high level of success in terms of regular season wins, and also in terms of success in state tourney play. Even with the team’s 22-7 record and the Golden Aces’ first conference championship in 15 years, Coach Bob Mirus was dismissed from coaching that spring. Archie Dees had his own dark shadow. A sports writer noted that the Grayville team, “had they still had Arch,” would have been as competitive as most of the bigger schools in southern Illinois.

________________________________________

It broke my dad’s heart when I started college in 1969 in Indiana rather than going to the small college in Illinois where I was going to play basketball. Dad had followed me religiously through my four years of high school play, three of them with my starting varsity. He attended every one of my games, watching my senior year as the Bluford squad put together a 25 game win streak. Dad was our biggest fan my last year, sending letters to the sports editor at the Mt. Vernon Register News, inquiring why the Bluford team wasn’t getting the same press coverage as the Mt. Vernon Rams. Ironically, it was the intensity of that last great season that wore me out, robbing me of the joy the game had brought me in the more meager seasons

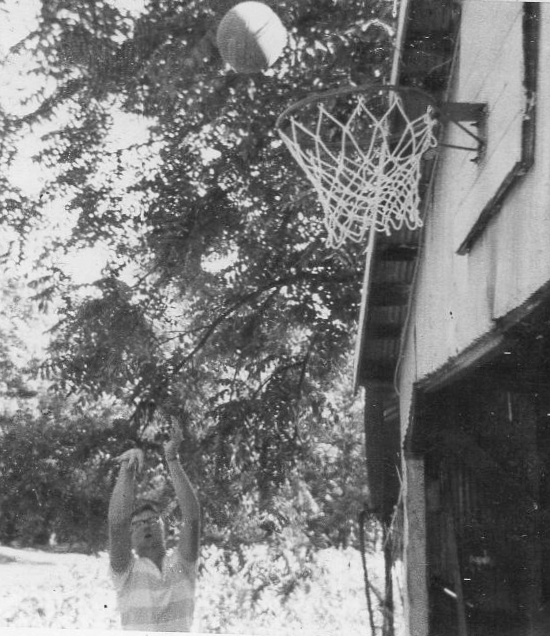

Out of guilt, I strung Dad along after high school graduation, letting him take me one Saturday morning in early June to talk to the coach and the admissions staff at Greenville College in Illinois. I received an official offer to play basketball, along with an academic scholarship. All the while, I knew I was done with organized basketball. When Dad and I got back home, I put on some old clothes and went out to the old dirt court to shoot around, finding a rhythm, blocking out the world, feasting on the sounds of the soft swoosh of the net. My mother, always handy with her camera, snapped a photo of me that day as I puzzled over what seemed an impossible dilemma.

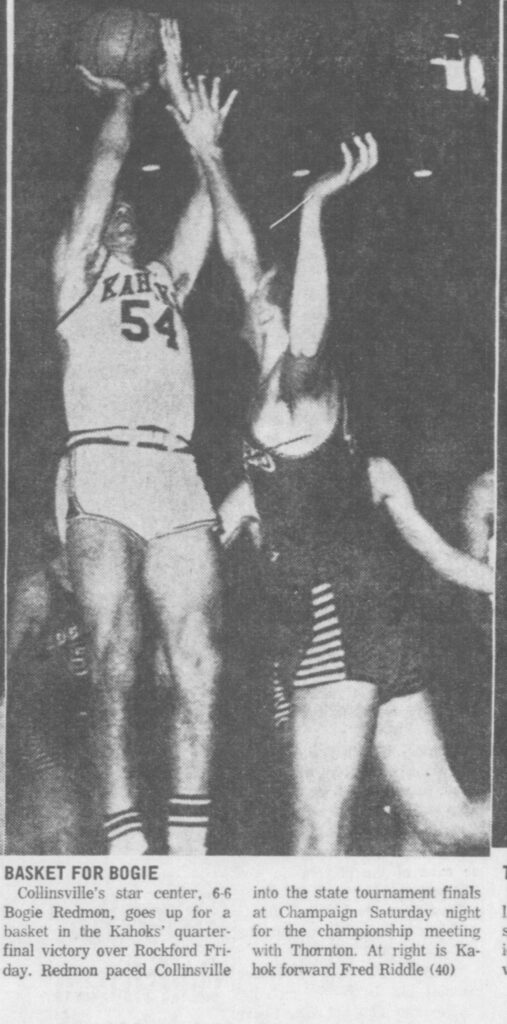

After college graduation, I did not return to Illinois to teach. Instead, I began teaching at a small-town high school at Loogootee, Indiana, in the fall of 1973. Now Dad had to listen to me tell about Loogootee’s great teams and their amazing coach, Jack Butcher. It hurt him too when I became an Indiana University basketball fan. When I was growing up, Dad and I watched the University of Illinois games on the television while we ate popcorn, cheering on Illini stars— Bogie Redmon, Tal Brody, Skip Thoren.

Dad and I really like Bogie, having watched him on television during another popcorn orgy when Redmon led Collinsville to an Illinois state basketball title in 1961. Later, I think in 1964, we watched Illinois and Redmon beat Indiana, and I remember asking my dad, “What’s a Hoosier?”

(Southern Illinoisan, 1961)

My devotion to IU basketball only increased when I started grad school at Indiana University in the summer of 1975, four years after Coach Bob Knight had come to Bloomington, Indiana. By 1975 Knight had put together one of the greatest college basketball teams of all time, immersing the state in basketball fever all hours of the day, like a torrid love affair.

I saw Bob Knight in the flesh, along with five other major college coaches, at the iconic high school basketball game between Loogootee and Springs Valley high schools in early 1974 at the Valley gymnasium. Knight’s height and burliness surprised me. But what made me really stand back away from him was the intense look on his face, a gaze that created a force field of space, one that warned he did not want to be bothered. Knight was there to scout a 6-7 high school player who could shoot, pass, and dribble like a guard, a kid named Larry Bird.

Loogootee won in a close, fierce battle that left players and fans exhausted. After the contest, I was still juiced up and excited. I wanted to call my dad and tell him, “I just saw the greatest basketball game of my life.” When I decided it was too late in the evening to call, I remembered for an instant the story Dad had told me about Archie Dees, and the greatest basketball game he said he had ever witnessed.

________________________________________

While Archie Dees was having a tough personal journey during his high school junior year, another young southern Illinoisan, not much older than Archie, was dealing with his own angst. Coming home from WWII, my dad took the handiest job available in the rural Horse Creek area of his birth, farming with our Grandfather Mills. After Dad married our mother, Mary Alice Newell, he purchased six sad-eyed Jersey cows that he milked and got cream from and raised chickens whose egg production, along with the cows’ cream, was used down at Leonard Wilson’s General Store to trade for groceries. But all was not well.

The arrival of spring and of the farming season was an exciting, uplifting time for many farmers, a call to the vocation they loved. For Dad, the spring brought only moodiness and despair. It wasn’t that he didn’t try. An article in the Mt. Vernon Register News in the summer of 1953 mentioned dad being selected by farmers in his township as one of seven men to serve on a county board dealing with Federal farm subsidies. Still, he was just not cut out to work in the fields. It probably didn’t help that my older brother, Marshall, and I came eleven months apart, followed two years after my birth by our youngest sister, Karen, leaving poor Dad going from the difficulty of a job he did not like during the day to a home after work that contained three needy rambunctious kids in diapers and an overwhelmed wife.

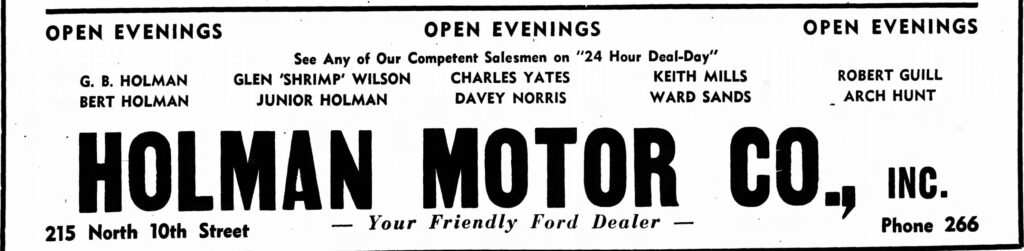

All this changed in 1953 when our then twenty-nine-year-old father began selling Ford cars for G. B. Holman in Mt. Vernon, Illinois. The story of how Dad came to snag the car salesman job at Holman Motor Company is lost with the passing of time. To us siblings, it’s the primary job we remember Dad having. One thing’s for sure: G. B. Holman must have been stunned by Dad’s immediate success, telling his other salesmen, “That boy sure can sell cars.”

The new job also brought a more subtle but still potent change. My dad reconnected with the high school basketball culture in the area.

Mt. Vernon in the early 1950s considered itself the center of high school basketball in southern Illinois, if not the state. By the 1952-1953 basketball season, the home town team, the Rams, had recently racked up back-to-back state titles and a third place trophy. One of the state championship teams had gone undefeated, and was said to be the best high school basketball team in the state’s history.

Dad was in basketball heaven. Trekking everyday across the alley from work to the little coffee and sandwich shop where he ate lunch, my dad was at once immersed in the intense and exciting conversations about Illinois high school basketball. Over cups of coffee and plenty of dry roast beef sandwiches, my dad listened and spoke among the noisy crowd coming and going there— car salesmen, state troopers and city cops, newspaper folks, avid fans, and occasional off duty high school referee officials. Hotly discussed were the upcoming games. There were arguments about what went right or wrong the night before, and, when the off duty refs weren’t there, complaints about bad calls. But the most exciting part of the basketball culture my dad fell in to was going to the games with his salesmen buddies. Whether they had tickets or not, they always figured ways to get into the crowded gymnasiums where the most important games took place.

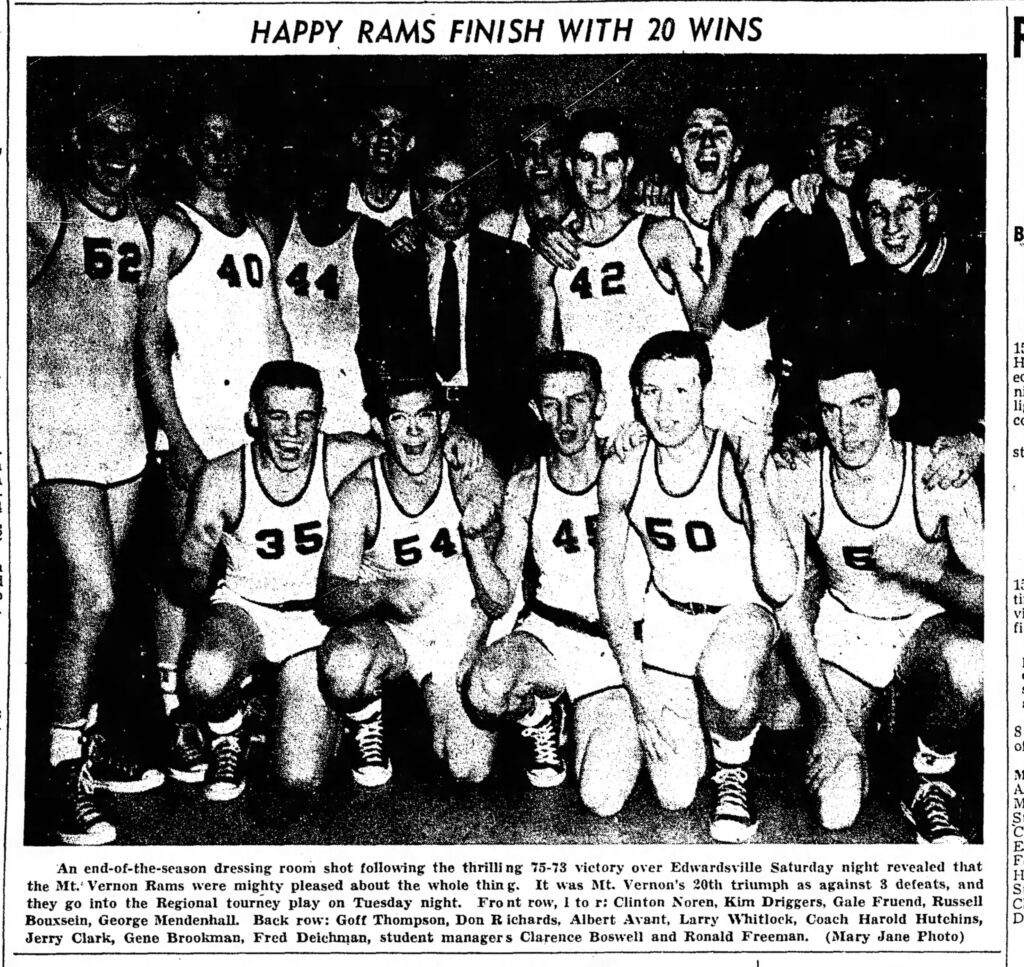

(Mt. Vernon Register News, 1953)

Toward the end of the 1953-1954 season it was a sure bet that Mt. Vernon would get to the final game of the sectional at Harrisburg’s Davenport Gym, the winner advancing on to the sweet sixteen state tournament. Dad and his car selling buddies began plotting how they could get tickets. The only unknown was who the Rams would face in their tournament journey.

Meanwhile, Archie Dees was on his own journey to the Davenport Gymnasium in Harrisburg.

________________________________________

Archie Dees only got better as his senior year progressed at Mt. Carmel. He scored 36 points against conference foe Fairfield in the season’s first game. At the Centralia Holiday tourney in December, the 6-8 Dees amazed coaches and the crowd when he was “used as a guard to bring the ball down the court against Marion.” At this juncture, midway through the season, an Illinois high school basketball referee, Harry Gaines, gave a Mattoon Journal Gazette sports reporter his opinion about The Golden Aces player:

I watched Archie Dees, the Mt. Carmel ace Friday night. This lad who stands better than 6-8 in his stocking feet is without a doubt the finest tall boy your writer has ever seem in interscholastic basketball. For the last seven years I have refereed up and down the state of Illinois and at no time have I run across a high school star like this Mt. Carmel ace. Terrific on defense, the lad is averaging 32 points a game, and the Mt. Carmel schedule is no push over.

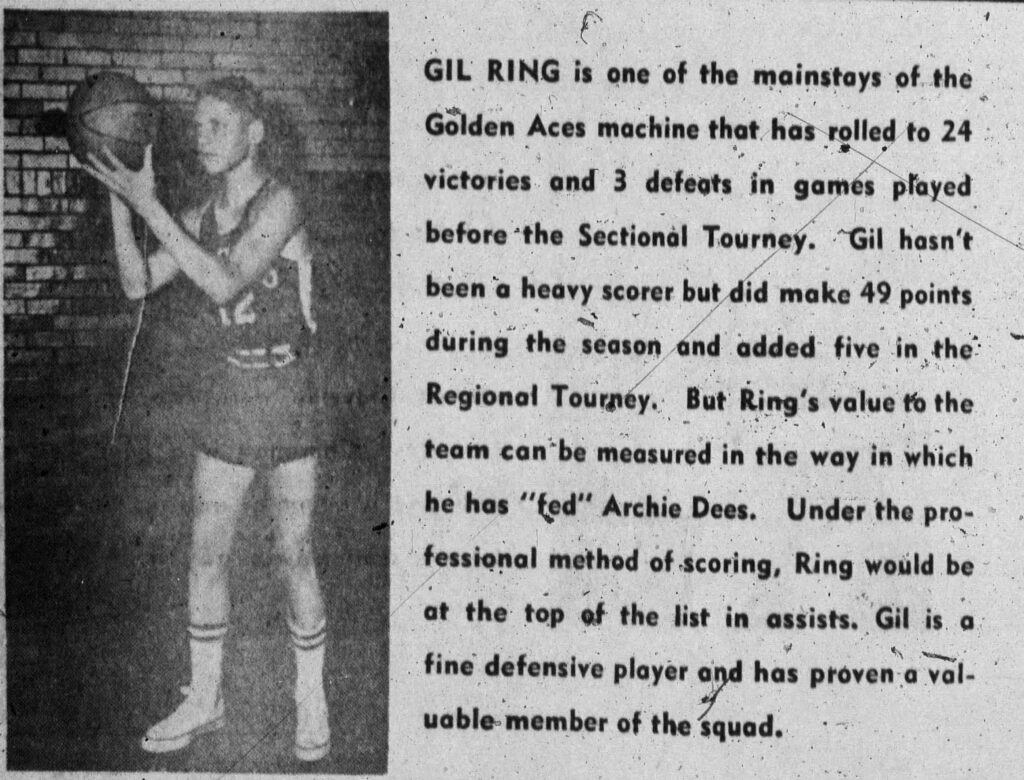

Not every sportswriter thought the Golden Aces, even with Archie Dees, would do as well as they had the year before. The concern was a lack of height. One described Dees as a giant surrounded by a “collection of midgets.” But the “midgets” got the job done. One of these smaller Aces players, Gill Ring, developed a special talent for getting the ball to Archie, a talent that did not go unnoticed by sportswriters. The Harrisburg Daily Register noted “In Gill Ring, the Aces have one of the best ‘feeders’ in the business, he being the boy who gets the good passes into Archie under the basket.” In the end, Gill’s passing and Archie’s ability to score almost at will made Dees the state’s leading scorer and left the Aces with a better record than the year before.

As state tournament time grew nearer and the drawings for each level of tourney play were released, a new tantalizing realization arose— It seemed likely that Mt. Carmel and Grayville would meet in the championship game of the regional tourney at Mt. Carmel. John Rackaway at the Mt. Vernon Register News played up the possible dramatic collision. “Grayville has a 14-0 record for the season. They handed McLeansboro its first defeat of the year and fans of the little Foxes tell us that Grayville is equipped with a 6-5 center and a pair of good forwards, both over six feet. The big boys and the 14-0 record should give Mt. Carmel food for thought.”

Seven games later, the Bisons were 21-0, causing one top referee official in the area to say Grayville had “a very good chance of ousting Mt. Carmel at the regional level.” The day before the Bisons/Aces showdown, premier sports writer Merle Jones noted, “”I don’t know how big the gym is, but it can’t be big enough to hold the crowd which will want to see the Mt. Carmel-Grayville game. Grayville is unbeaten in 28 straight games.” Another reporter playfully declared, “I wouldn’t want to be the ref at that game.”

(Harrisburg Daily Republican Register, 1954)

The next day’s reports of the game were even carried in the Evansville, Indiana Press. “The Grayville five had come to Mt. Carmel with fire in their eyes.” It was not a fairy tale ending, however. “With a jammed crowd of 2600 spectators looking on, the Aces with big Archie Dees directing the masterful attack, took command at the start to hand the Bisons their first setback in 29 games this year.”

In fact, it was a massacre. Dees led the Aces, rolling up 42 points in a 102-59 victory. Perhaps Archie was venting his anger at the folks who came to Mt. Carmel and threw stuff at his family’s house after the Dees’ left Grayville. Perhaps it was suitable revenge. Of course, in high school basketball, there was always plenty of karma to go around.

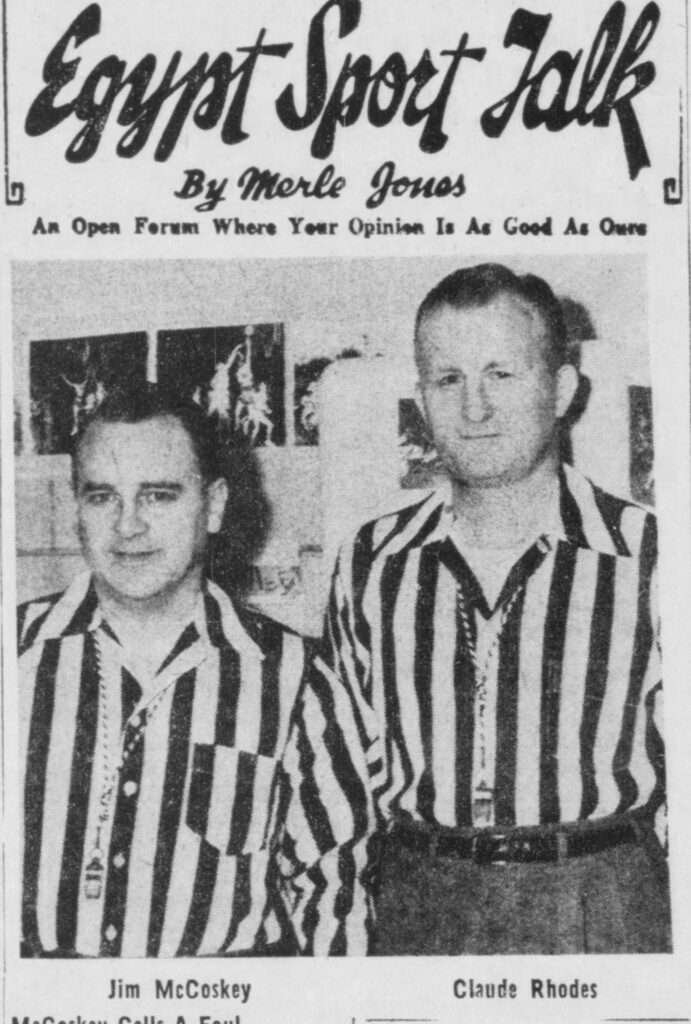

All eyes now turned to the Harrisburg sectional. Mt. Vernon was ranked throughout the 53-54 season and looked to be on a collision course with Mt. Carmel. Many “experts,” including the ones at Dad’s sandwich and coffee shop, thought the Rams squad below par when compared to other recent Mt. Vernon teams. The Rams were vexing to the experts, having no one dominating player but working well as a unit, ending the regular season with 20 wins against some of the best completion in the state. They did have a fast little floor leader, Albert Avant, who had changed the course of a few games in a minute’s notice. Top regional referees Claude Rhodes and Jim McCloskey were calling the Harrisburg sectional that year, their highly respected expertise adding to the sense of a great game in the making.

(Mt. Vernon Register News, 1954)

While my dad and his car salesmen friends could not seem to get tickets, they made plans to go there and take their chances on getting in. As it turned out, there were tickets available for Dad and his friends at the door, officials having accidentally oversold the seating spaces, leaving the question of where to sit as an interesting issue.

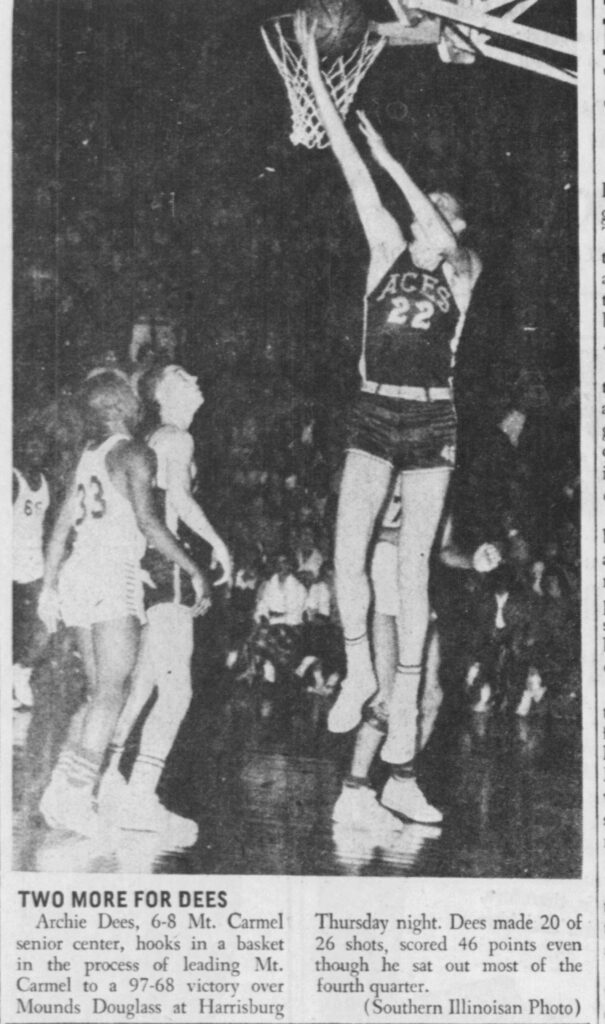

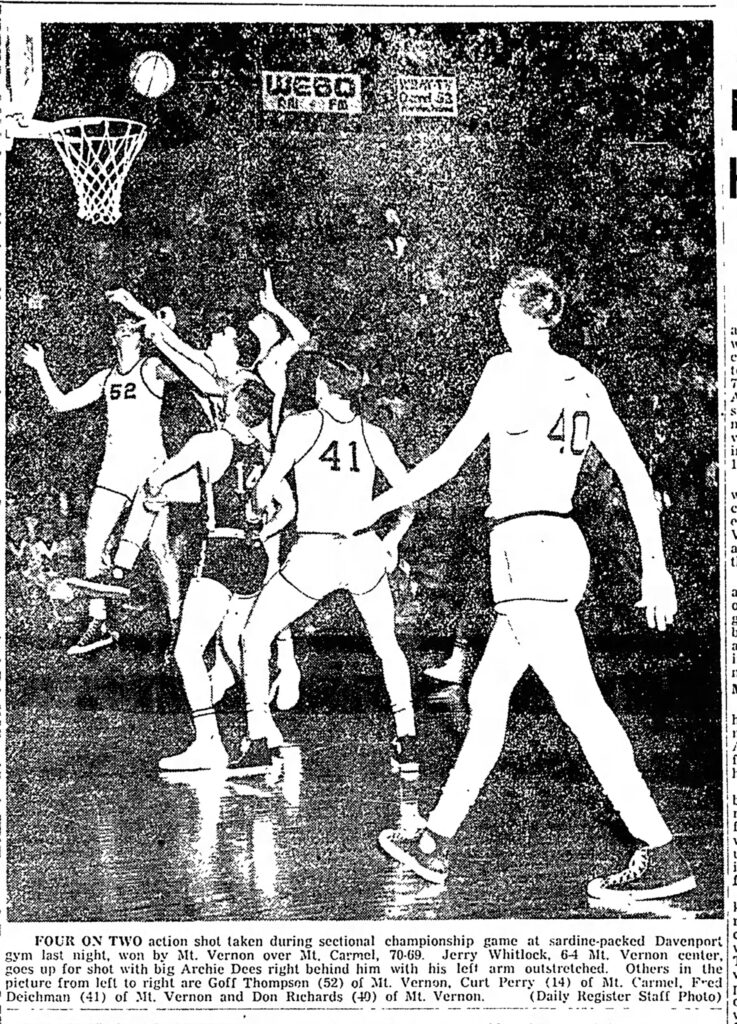

The Holman car salesmen crew watched Mt. Vernon smash Metropolis 89-67 and Archie Dees destroy Mounds Douglas by scoring 46 points hitting 20-26 shots from the field. The latter game shook the faith of many Ram fans, including my dad.

(Daily Republican Register, 1954)

The next night would be D Day. It was a game many southern Illinois basketball fans had seen coming, and with great anticipation, and my dad, Keith Mills, would be there.

________________________________________

Harrisburg school officials had never seen anything like it, the pulsing excitement, along with an undercurrent of unrest. A sports writer for the local paper, the Daily Register, noted the next day, “Never has such a crowd been seen in Davenport gym.” An hour before the game, the seats were all but full, “and the fans kept pouring in.” Fans were soon “jammed into every nook and cranny, sat all over the floor, and even hung on the goal posts. It was one of the greatest games ever played in Harrisburg, and the greatest sports crowd in the history of the town.” Attendees came from near and far but most observers agreed Mt. Carmel had the most supporters, southern Illinoisans loving an underdog. But Rams fans were fanatic, having had so much success in tourney play, and once in the gymnasium their individual support merged into a constant, fluctuating roar.

(Southern Illinoisan,1954)

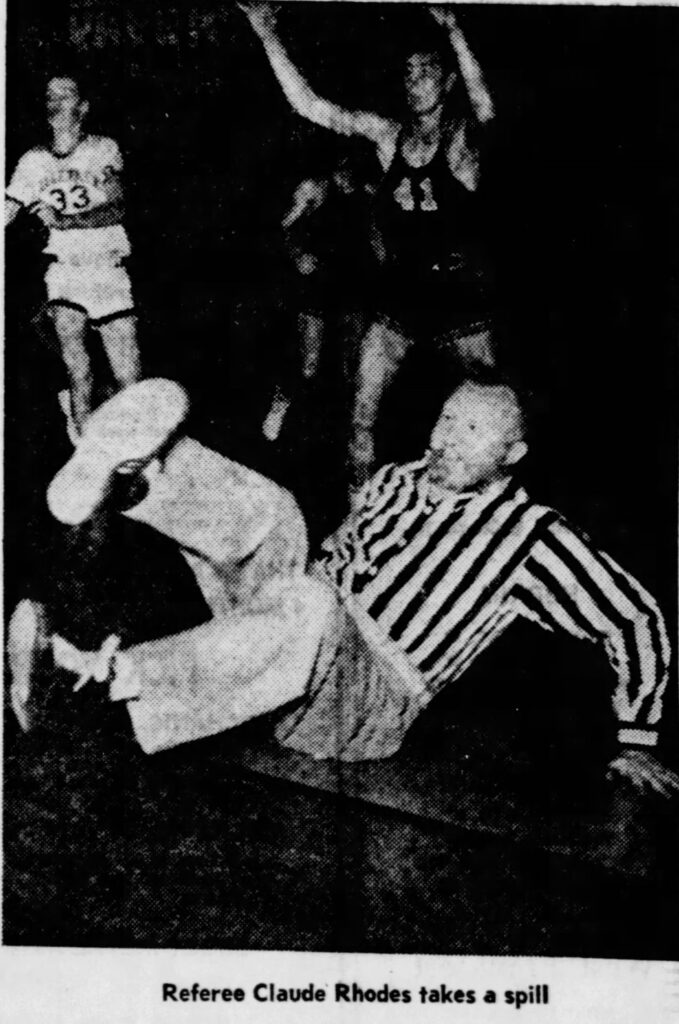

My dad and his buddies were lucky to find, close to the Mt. Carmel bench, a crowded niche at the edge of the floor in which to sit. They had barely snuggled down when the two referees, Jim McCoskey, and the taller Claude Rhodes, called the players to the floor. Both refs were well known for their confidence in making fearless calls.

The first quarter flew by, the teams trading baskets and Dees having a hot hand. When the horn sounded to end the quarter, the Aces held a four point lead, 17-13. Then the Rams got hot from long distance, little Albert Avant throwing up several on-the-mark shots. His accuracy pulled Mt. Vernon into a tie and then a four point lead at halftime.

(Harrisburg Daily Register, 1954)

At the half, not a single fan in the overflowing crowd felt confident in their team’s winning. And few left their seats, wherever and whatever that was, to visit the concession stands. The noise stayed at a constant level, like an ominous hum.

The beginning of the second half was a disaster for Archie Dees and his teammates. Just seconds before the horn sounded to end the quarter, Mt. Carmel Aces’ Jack Brown hit a basket, leaving Mt. Vernon with an eight point lead. With this lead my dad, his buddies, and a couple thousand other Rams followers were a bit more relaxed when the final quarter started. Then in the blink of an eye, the Aces got two quick baskets, the second by Dees underneath. The Rams were only up by four, 55-51.

The gymnasium was all but rocking. My dad, whose right hand would twitch whenever he got nervous, probably looked like he was waving at someone out on the floor. Then Mt. Vernon’s tallest player, Larry Whitlock, fouled out, giving Archie more leeway. The Aces tied the score with three minutes to go.

Then Boom!

Jack Brown hit a 25 footer from the side and Mt. Carmel finally had the lead back, 65-63.

Not for long.

The Rams made a foul shot and Golf Thompson hit a corner shot, pushing Mt. Vernon back into a one point lead with 1:40 left in the game, the screaming fans near exhaustion, almost as sweaty as the players.

Archie was scoring ahead of his 30 point average at this juncture, on his way to 38 points, making a hook shot and hitting two free throws to give his team a three point lead with a minute to go. That lead held until the last few seconds in the game.

Don Rich stole the ball from a Mt. Carmel player and went down for a lay up attempt. GOOD! The Rams were down a point but only nineteen seconds remained on the clock.

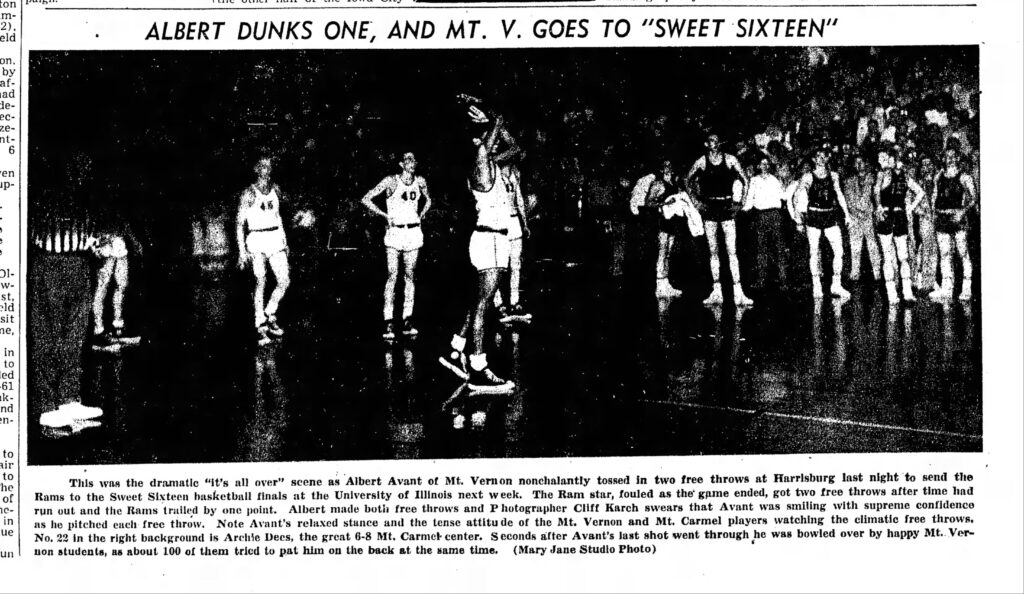

Mt. Carmel’s Johnny Cox had just dribbled to the half court line when quick as a cat, Albert Avant knocked the ball away and headed down court towards the Rams’ basket. Cox, in a panic, lunged and slapped at the ball, tumbling to the floor as he did so. The horn sounded and Aces fans began storming on the floor when ref Claude Rhodes blew his whistle. He indicated to the scorer’s bench that Cox had fouled Avant, sending the Ram player to the foul line with no time left on the clock and the Aces ahead by a single point.

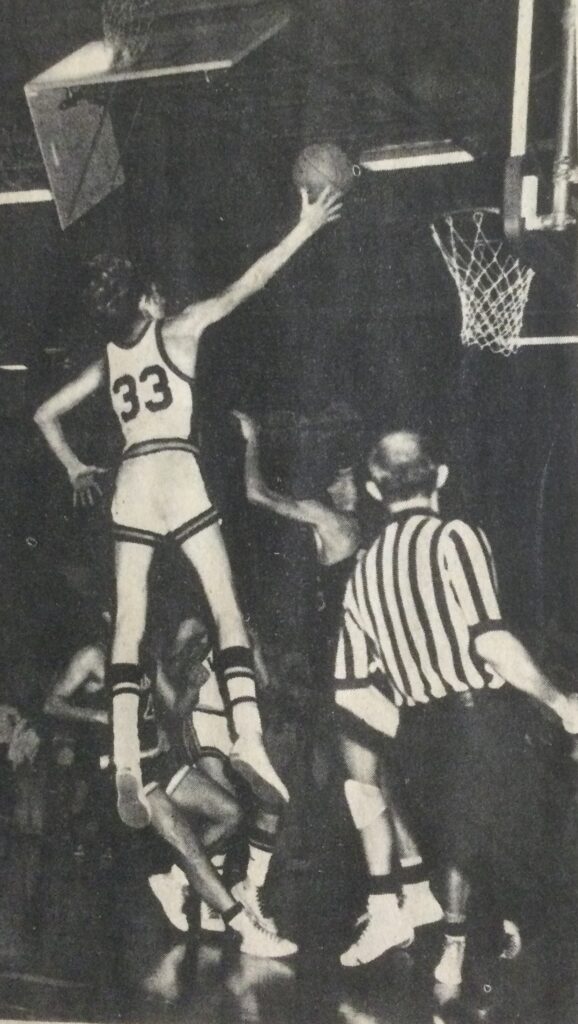

Mt. Vernon went on to win the state tournament that year, causing the Davenport contest to be somewhat forgotten Fortunately, the grainy photo that appeared in the Mt. Vernon paper the next day after Mt. Vernon’s sectional victory over Archie Dees and the Golden Aces preserved the story. A smiling, confident Avant hit both shots, and it was Mt. Vernon who did the final court storming. In the photo you can see a worried Archie Dees and other of his teammates looking on as Avant nails the coffin shut. And just behind Dees stood my dad, taking it all in, the greatest basketball game he ever saw.

_____________________________________________

My mother sent me a long letter almost every week during my college days, keeping me posted on what was going on back home. I sent back maybe a dozen responses, too busy with classes, activities, and discovering who I was to write back much. Mom was never one to lay guilt, but one theme of her correspondence did run something like his— “Please write or call your dad.” “Dad’s having a hard time,” “Give your dad something to cheer him up.”

Much of Dad’s “hard time” came about when he quit selling cars and began working for the Illinois Department of Transportation. The transition was difficult until he became an inspector for IDOT, a job that allowed him to get out and travel in the region and talk to more people again. I’m sure many of those talks included comments and thoughts about basketball.

Once out of college, I did begin talking over the phone with Dad occasionally about basketball. Through this part of the seventies he had to take it on the chin whenever my Hoosiers played the Illini. Then came the January 7, 1978, Saturday afternoon game at IU. Illinois won a nail bitter, 65-64, with the Hoosiers blowing a last second shot when Jim Wisman made a bad pass and Illinois got back the ball. I could only imagine what Bobby Knight had to say to his poor players. My phone rang at home as I was watching the Illinois players and fans celebrate and an angry Bob Knight walking off the court.

My Dad was elated, and for some reason I said nothing about the poor game IU played or the fact Illinois was just lucky. I am glad I kept quiet. His voice was rich and deep, his laugh, animated. I did not know this would be the last time we would talk.

The 1978 Blizzard began in Illinois/Indiana on a Wednesday, January 25. This was the first blizzard warning ever issued for the entire states of Illinois and Indiana. The storm packed fifty mile per hour winds and heavy snow that drifted over roads, in some places over three cars high. Many areas receive up to 20 inches of snow that was followed a few days later by more snow, wind and cold. Schools, stores, hospitals, roads, everything was shut down. Most everything that is but the Illinois Department of Transportation. Working conditions were life threatening for the IDOT people. Then, a few days later, came another round of snow, wind, and cold.

My dad’s state car had to be jumped that morning of January 30, and as he walked out the back door of our house, Mom said, “Don’t go in today.” Dad replied, “I’ve got to.”

When Dad did not come back in right away to warm up while the car ran, Mom sped out the door without a jacket or coat. She found him in the front seat, lying to the side. He was dead of a heart attack, his work sheet on his clipboard just signed in.

It was only as I was writing this story that I realized his car was parked beneath the backboard and goal he and Grandpa had put up for me back in those days when my fledgling basketball career was so full of hope, a blank tablet waiting to be filled with stories of wins and losses, and lessons of great value—some hard and some joyful— of the sounds of fans screaming their hearts out in small-town gyms, and the journey of the small-town hero.