Stories of iconic American figures can often become stale, losing much of their meaning in their repeated tellings from generation to generation. Consequently, it is good to look at new angles of any of these older narratives in order to freshen up and further flesh out our understanding of important figures whose lives have somehow come to speak to the American psyche.

One such iconic figure is basketball great Larry Bird, whose phenomenal basketball skills are still analyzed and debated today. Upon his retirement from professional basketball in 1992, national newspapers simply gushed with stories of his amazing accomplishments, but it would be hard to top what Larry Tye, at the Boston Globe wrote. “Larry Bird was the individual microcosm of everything good about both basketball and sports itself.”

But more than anything else, I believe that Larry’s story is that of an underdog, perhaps the most resonating of all American heroic story forms.

Larry grew up in a section of southern Indiana where the landscape was framed by picturesque but rugged hills, living in the gone-to-seed twin resort towns of West Baden/French Lick. It had not always been that way.

In 1855, an inn was built in West Baden to take advantage of the mineral springs there. Eventually, an owner built a fabulous resort hotel, one which contained the largest dome roof in the world in its day. All of that splendor was lost, however, when the Great Depression struck. In nearby French Lick, a resort Inn also sprang up, one that would rise to international prominence, much of it based on the illegal gambling operations in the community.

By Larry Bird’s day the domed resort stood in disrepair and the French Lick resort was a bit ragged and rundown. (The towns have now been revitalized today by the presence of a legalized gambling casino.) At the time of Larry’s birth, the region was the poorest area of the state.

In his autobiography, Drive, Larry noted, “Growing up wasn’t easy for me. My family didn’t have much, so we appreciated anything we had. … Money was always an issue with us.” Larry was the third of six children, with four brothers and a sister. It did not help matters that Larry’s father, Joe Bird, probably suffered from PTSD, having experienced brutal combat in the Korean War, a situation that only accelerated a drinking problem. On the upside, both Larry’s mother and a grandmother were extremely involved with the Bird children, given them daily physical and emotional nourishment.

Perhaps the next greatest saving grace for Larry and his siblings was sports. In Drive, Larry explained, “First of all, sports was a big part of our lives every day. There was a never a day we didn’t do something, whether it was baseball, basketball, or football.”

The depth of the difficulties Bird faced growing up are not completely understood, however. One of his biographers, Mark Shaw, has pointed out how Bird’s fierce protection of his personal life left so much of his early struggles lingering in the shadows.

This piece seeks to add some new details to Larry Bird’s story, his all but magical sudden appearance as a high school basketball superstar. Perhaps the most surprising item to emerge from this research was the role of one small-town sportswriter, Jerry Birge, of the Jasper Herald, in first bringing Larry Bird to public light, although Bird played at a rival school. Birge certainly got it right, his often pithy descriptions and accolades concerning Larry’s play eerily similar to what other national sportswriters in the far future would write again and again about Bird’s often unbelievable game accomplishments.

There is a personal angle for me in this story as well. I first laid eyes on Larry Bird before he was Larry Bird, that is, before he became famous. I would have a couple of other encounters with him two years later, at two different Indiana high school basketball games.

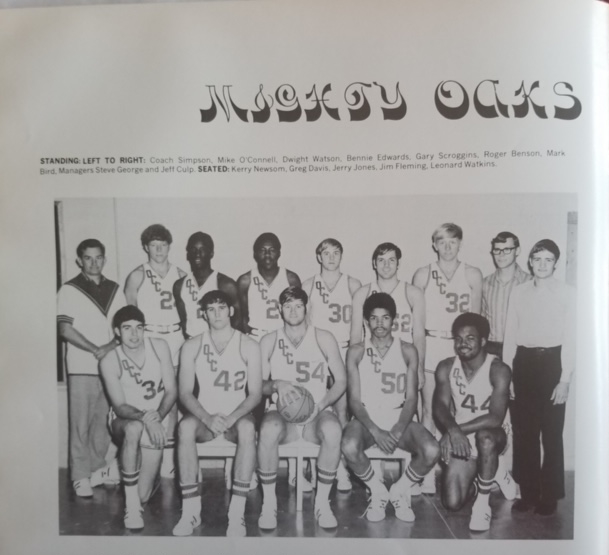

My first encounter with Larry occurred because his older brother, Mark, attended Oakland City College on a basketball scholarship. I was two classes ahead of Mark when he came to OCC as a freshman in 1971-1972. Larry would have been a sophomore then at Springs Valley High School in French Lick, Indiana. Larry missed most of that high school year playing basketball that season, due to an injury, and his future in that sport looked to be so-so. On the upside, I guess it gave him time to come see his brother play at OCC.

Oakland City had maybe five hundred students on campus when Mark Bird showed up, and the Mighty Oaks basketball team played at the N.A.I.A. level. They went 19-7 Mark’s first year, going undefeated at home.

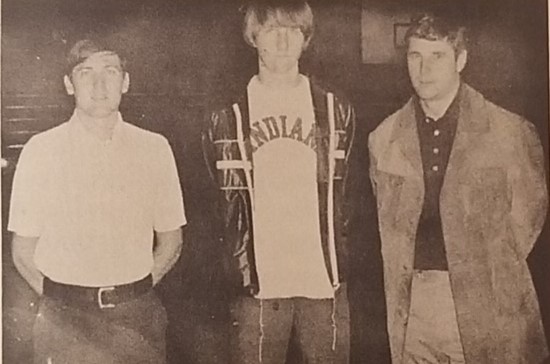

Mark was 6-3 and was a solid shooter, but I do not remember Mark getting much playing time his year as a freshman at OCC. I would see him around on campus, enjoying the college experience. Larry sometimes came to his brother’s basketball games and stood out, not because he was famous, but because he looked so much like Mark.

I remember Larry having cast-down eyes whenever people made eye contact with him. He seemed extraordinarily shy.

Later, a tradition spun out of Larry’s attendance at these Mighty Oaks games, the story being that he wanted to come play basketball at OCC because his brother did, and because the school seemed small and safe for his quiet demeanor. Larry also probably realized that if he came to Oakland City as a freshman, he would be on the team with his senior brother.

This story makes some sense, as Larry had not yet exploded into greatness. By the time he was a senior in high school, however, he was being heavily recruited by several major schools, including Indiana University, the University of Kentucky, and the University of Louisville, among many others.

But continuing the thought that Larry that may have considered coming to OCC for a while, the Bird family was, as noted, large and very poor, and Larry pointed out in his autobiography how, “Mark went on a scholarship to Oakland City College. When Mark went to the college, he said to the family, ‘When I get out, I’ll be a big businessman and make millions of dollars and take care of you.’ Mark was always watching out for us, sharing anything he had with us, sometimes slipping us younger kids a dollar or two whenever he could.”

I suppose to Larry Bird at that time, going to Oakland City College would have seemed like a big deal.

______________________________________________________

Speaking of Mark Bird, if you would have had to of bet, you would have likely put your money on Mark being the athlete that would bring the most fame to his family. As it was, his senior year basketball play set off a spark in his little brother’s mind and soul about playing basketball.

Up until his freshman year in high school, baseball was the game Larry was most interested in. He even quit his eighth-grade year in basketball when he got mad at his coach.

As a freshman B-team basketball player in high school, Larry would only get into the games “at the end,” and rarely stayed for the varsity games. However, playing on the B-team did cause Larry to finally attend his first varsity game, going to see Mark play as a senior in his last game of the regular season. The experience awakened something inside him. He recalled the moment in his book, Drive. “The first time I ever went to see a [high school] basketball game was when my brother Mark played in his last game. It was a real close game and Mark wound up being fouled. He had to make some big free throws. I was so scared we were going to get beat, but we won. There were tears streaming down my face and I remember thinking, ‘What’s wrong with me? This is what I’ve been missing by not going to these games?’”

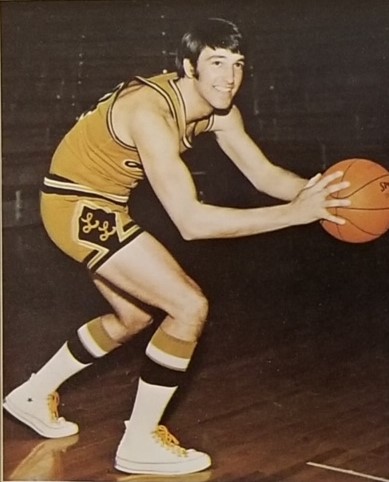

Mark’s senior year ended up with his achieving the highest scoring average for the team at 17.8 points a game, blocking the most shots and having the best free-throw shooting percentage, making the Blue-Chip All-Conference first team, and obtaining second place on the all-time basketball scoring list at Springs Valley.

Lost to most people in the basketball statistics for the Springs Valley team that year, however, was a short piece in a Bedford newspaper that noted, “The freshman free-throw trophy was presented to Larry Bird. Larry hit 65 per cent of his free ones.”

This may have been the first time his name appeared in any newspaper that related to basketball.

While having an epiphany about playing basketball his freshman year while watching his brother make the winning points in a basketball game, Larry’s own journey to basketball greatness was sidelined his sophomore year of 1971-1972 because of an injury. However, the determined young man, now six feet tall and almost pathetically thin, shot around while on crutches. Then, in late February of 1972, another event involving basketball occurred that awakened Larry even more to the excitement and potential of the game.

The beginning of Indiana high school basketball tournament time witnessed an even greater interested in local teams during a season. Every game could be a team’s last, and luck often smiled in the form of unexpected upsets. Dramatic endings left fans and players limp, and the sectional gym sites were always packed in the 1970s.

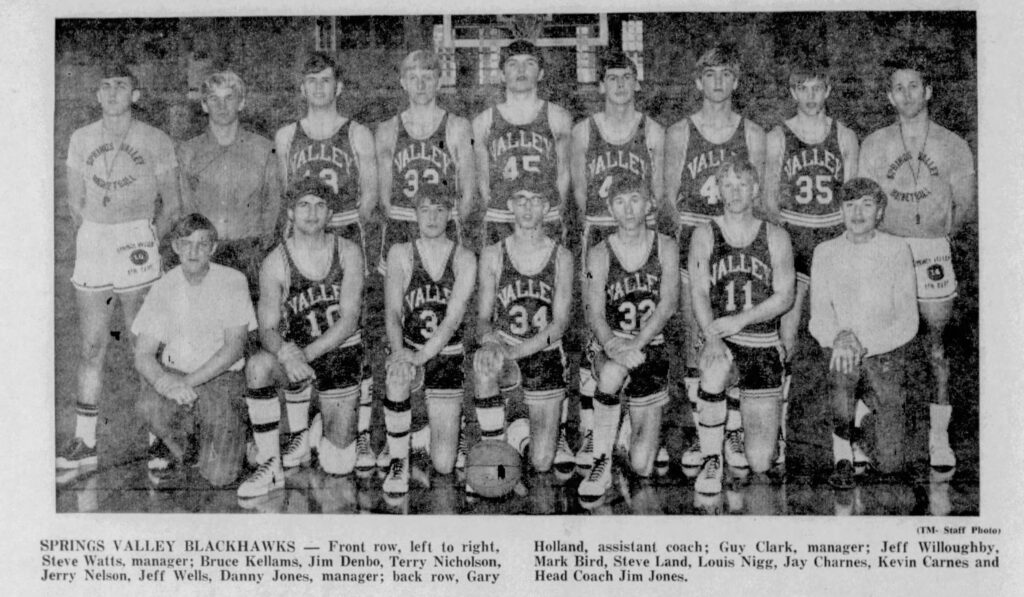

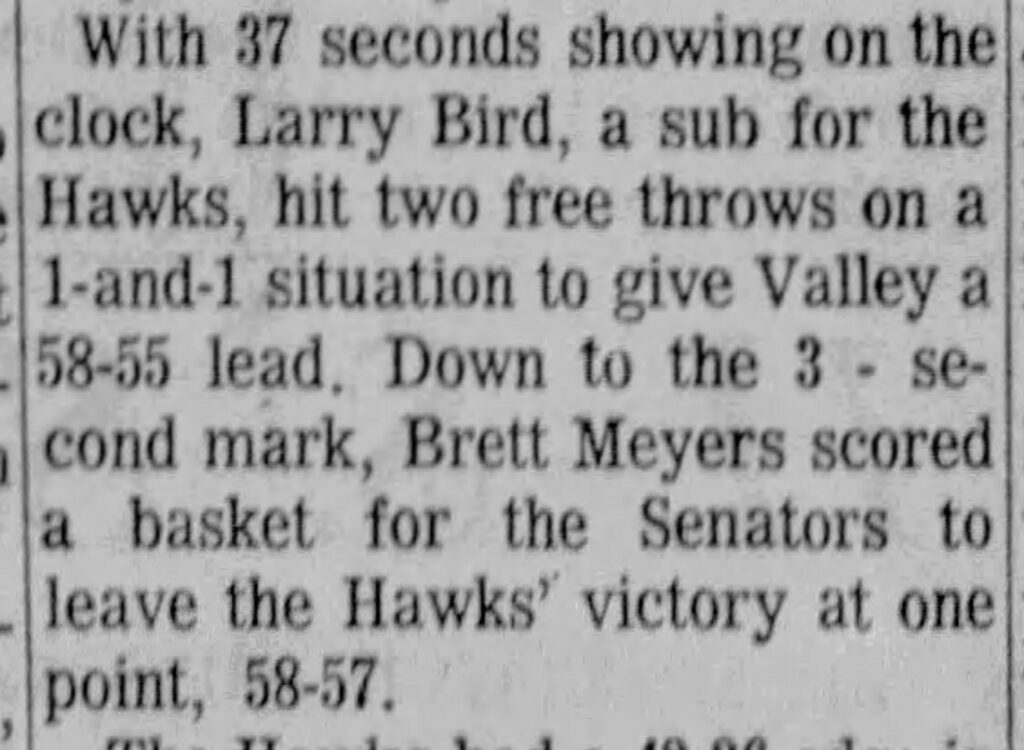

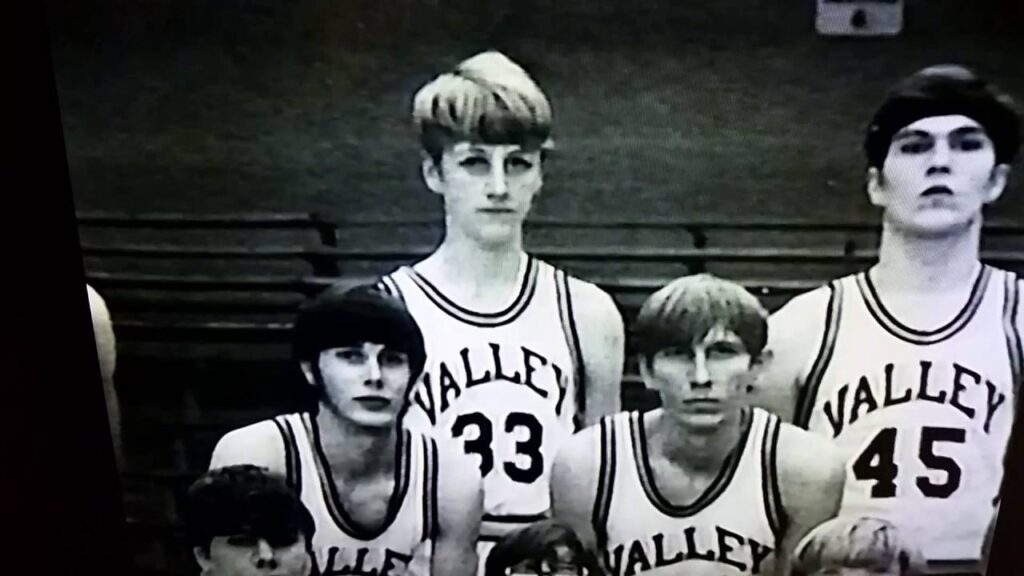

In a sectional game at Paoli at the beginning of the 1972 sectional, the Springs Valley Blackhawks were in a close game against the West Washington Senators, and Larry was riding the bench, finally out of his leg cast and proudly wearing his brother’s old jersey number, # 33.

Valley had built up a large lead before West Washington came back and outscored the Blackhawks 24-4. West Washington led the game by two points at the end of the third quarter. The fourth quarter continued to be a nail-biter, the lead swinging back and forth several times, the fans out of their seats, screaming support for their teams.

As the contest wound down to the last couple of minutes, Larry, unexpectedly, heard his name being called by the Coach Jim Jones. He was put into the game during the last few frantic minutes of a dramatically close sectional game in a gym that was all but rocking with excited screaming fans.

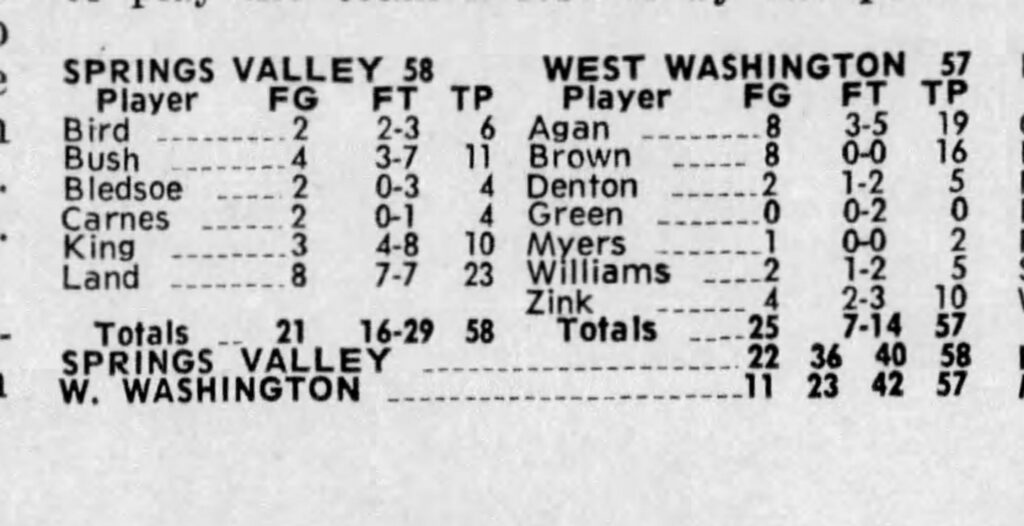

The Bedford Daily Times-Mail reported the next day,“With 37 seconds showing on the clock, Larry Bird, a sub for the Hawks, hit two free throws on a 1-and-1 situation to give Valley a 58-55 lead.” West Washington would score another basket in the very last seconds, but Larry’s free-throws ended up winning the game, just like his brother Mark’s free throws had won the game in the first high school contest Larry witnessed as a freshman.

The Bedford newspaper article would be the first of hundreds of sports reports telling of Larry Bird’s heroics on the basketball court. When Larry spoke of the event in the book, Larry Legend, he said, “My heart was pounding, and I threw my warm-up jacket off and was at the scorer’s table [to check into the game] before I even knew it. The first time I got the ball, I launched it from 20 feet, and it went in. The crowd went absolutely crazy while I’m passing everywhere, rebounding, sinking all my shots.”

Interestingly, the box scores in a Bedford, Indiana, paper showed Larry made the two free-throws that won the game and made one basket, but overall, he was only 1 for 9 from the field. The Louisville Courier-Journal account, however, was closer to Larry’s memories. This account had the clock down to thirteen seconds when Larry went to the foul line. “Valley had enough to come back—thanks to Steve Land, who finished with a game high 23 points, and sophomore Larry Bird, who scored six points as Valley held on in the waning seconds.” The opposing coach noted, “Bird’s two free-throws were the clincher.” The Louisville paper headlined the article, LAND AND BIRD PROPEL SPRINGS VALLEY 58-57.

Whatever Larry’s exact scoring total, he had experienced his first rush of basketball glory, making the two free throws that won a sectional tournament game, but, as either box score indicated, he was a long way from any level of greatness. It was after that game, however, that Bird said he started listening to and applying everything his coach explained about basketball, items that included every fundamental part of the game. And Bird began practicing these skills to the point of obsession.

______________________________________________________________

Mark Shaw, in his book, Larry Legend, noted that “Larry Bird appeared almost as if by magic. Somehow he catapulted from being a decent player his junior year to one of the finest high school seniors in Indiana history.” Interestingly, there is not much detailed information available about Larry’s junior and senior high school years in books or sports articles. However, a deeper story of Bird’s explosion on the scene can be found in local newspaper sport pages.

It is amazing, on looking back at an early report in a sport page article in the Bedford Times-Mail about the upcoming Springs Valley 1972-1973 basketball season, that Larry Bird, now a junior, was not even mentioned as a returning player who would receive possible playing time. In part, the article explained, “Springs Valley returning lettermen include Jay Charnes, Tony Clark, Danny King, Steve Land, Louis Nigg, all seniors, and juniors James Carnes and John Carnes along with sophomore Brad Bledsoe.”

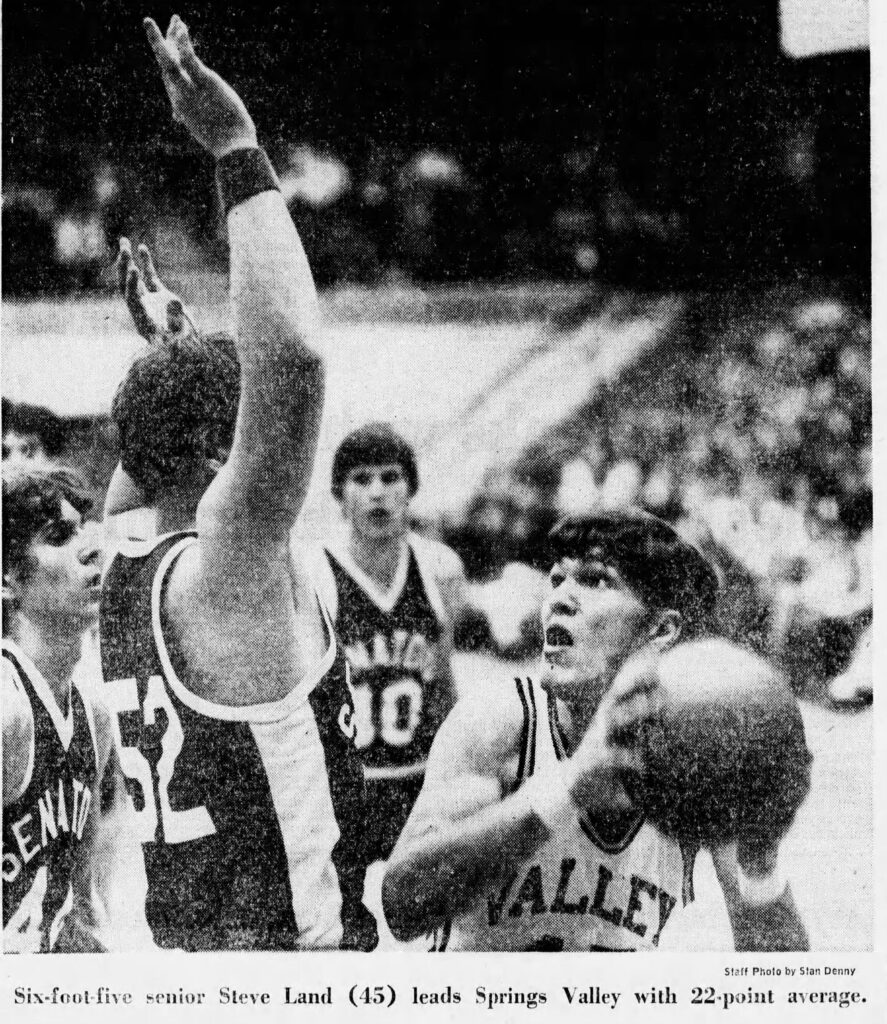

Steve Land, at 6-5, would be their leading scorer that year and was solid enough as a player to receive attention from several universities and colleges. He eventually went to Indiana University, but ended up getting cut from the team.

Bird was now 6-3, and prior to the season had worked amazingly hard on dribbling both right-handed and left, as well as working on passing and shooting. Regarding his passing endeavors and how he got so great at it by his junior year, Bird explained in Larry Legend, that he knew Steve Land would “handle the scoring.” With that in mind, Bird concentrated on improving his passing in innovative ways. He fell in love with the kick he received any time he made a pass that led to someone on his team scoring. [On an outdoor court] “I’d pass the ball off a wall, off the fence, didn’t make any difference. If other guys score, you see the gleam in their eyes. Besides, passing is more of an art than scoring.”

When Steve Land was trying to break a Valley scoring record in a game and gain recruiters’ attentions but was frustrated that no one could get the ball to him, Bird begged Coach Jones to put him back into the game so he could get the ball into his friend’s hands. Jones did so and Larry did the rest. Steve Land was able to break the record.

Sharp-eyed and colorful Jasper Herald sportswriter Jerry Birge was the first news reporter in the area to take even a brief notice of Bird after the Blackhawks had gone 4-0 at the beginning of the 72-73 season. He reported Valley’s “[Steve] Land, one of the top individuals in the area, is averaging 22 points a game. Also in double figures for the Hawks are Bird (13), Clark (12), and Carnes (11).”

It was in the Blackhawks’ fifth game that year against Jasper, a regional basketball powerhouse that the Coach Jones told Bird he needed to start scoring more. Larry explained in Drive, “At halftime we were down by six or so and Coach Jones says to me, ‘If you don’t start shooting the ball, you are going to sit next to me and you are not going to play anymore. You are hurting the team by not shooting when you are open.’” Bird did so and ended up averaging 16 points a game, following Steve Land in total points and gaining an eye-popping near 10 assists per contest. The team went 19-3 that season but lost in an upset in the sectional round of the state tournament at Paoli to the host school.

When the Valley basketball awards night came to recognize the achievements of the 1972-1973 team, Larry Bird was a no-show. Coach Jones rushed out to find him shooting baskets at the city playground and convinced him to come to the banquet. In Larry Legend, Larry’s senior year high school coach, Gary Holland, remembered thinking at the end of the season, “Larry was a good player, but not a great one. I never thought he could be that good.”

At best, Holland could image him attending a small school such as Oakland City College like his brother, Mark. Further, Larry was on no one’s recruiting radar. But not even Larry could have imagined the magic the next season would bring.

_________________________________________________________

While Larry Bird was about to have his breakthrough season, I was having my own Indiana high school basketball adventure, howbeit as a fan. In September of 1973, I began my very first teaching assignment at Loogootee High School in Loogootee, Indiana. About a week before classes, on a Saturday, my dad came over from southern Illinois to Jasper where I lived so he could go with me to see where I would be teaching.

It was not an easy drive up to Loogootee. In southern Illinois, I had played on an exceptionally good high school basketball team my senior year in high school, and Dad wanted me to continue to play at a small nearby college so he could continue to see me play. It was that year that our mutual love for basketball drew my usually depressed and moody Dad and me closer together. But I did not want to play basketball in college. Instead, I accepted an academic scholarship to Oakland City College in Indiana.

Things only got worse when I accepted a teaching job in Indiana, instead of coming back home to Illinois to teach. Needless to say, as we traveled to Loogootee, I hoped Dad would come around when he saw my first classroom and how excited I was about teaching.

Instead, something else unexpected saved the day.

The first thing we noticed when we walked into the foyer of Loogootee High School was its packed trophy cases. I was stunned, and I think Dad was too. I said, “Wow. Look at this one,” and I read the inscription, and then Dad said, “Hey. This one beats that.” The one that took the prize, however, was the trophy for Loogootee’s trip to Indianapolis to the final four basketball tournament three years prior.

I knew Dad was hooked when two future students of mine, Jeff Meyer and Wayne Flick, walked into the foyer from the gym. Dad instantly turned into his charming self, but I could tell he was truly impressed by this tiny school’s basketball successes in a single class system. He turned ecstatic when Wayne Flick told him he was a senior and played on the team. Jeff, Wayne explained, was the student manager.

“Guess you’ll go all the way to state this year,” Dad asked.

“You bet,” said Wayne.

I was embarrassed later that day, thinking about my dad’s silly question, wondering what the two soon to be students of mine might say to their friends about the new teacher, the one with the tag-along dad who asked silly questions. Of course, what did I know? The next year Loogootee made it all the way to the final game of the state tournament. At that moment too, I was pleased by my dad’s sudden happy demeanor. He now seemed okay with my new job, maybe even a little bit excited.

“Keep me posted on the team,” he said when he and Mom left to go back to southern Illinois.

My old basketball interest was fired up too. At Loogootee, I found myself enjoying the excitement of a game again, cheering on a team I identified with, especially when watching a well-played game or an exceptional individual performance.

I quickly inquired among my fellow teachers at Loogootee as to the school’s amazing basketball successes. Lee Kavanagh, who I carpooled with every school day from Jasper to Loogootee, and who was the Loogootee eighth grade basketball coach, told me, “We have the best basketball coach in the state, Jack Butcher.”

Several years later, when Jack Butcher finally retired, he was the winningest high school basketball coach in the state.

Going to the Loogootee basketball games my first year of teaching was a blast, the home gym for each game sold out with more totally energized fans in the bleachers than the town’s entire population. It brought back memories of the excitement of my own high school basketball days, and how our team’s successes brought the community together. I often went to Loogootee away games too and especially enjoyed traveling with Lee, who gave me interesting background concerning the issues the Lion’s would face against each team.

The Lions would go undefeated deep into the season and gained state ranking. Playing in the Blue Chip Conference, their primary opposition in the last few years had been Springs Valley. Interestingly, at the beginning of the 73-74 year, there had yet to be any talk of a player named Larry Bird, not even from Lee Kavanagh, but that would soon change.

___________________________________________________________

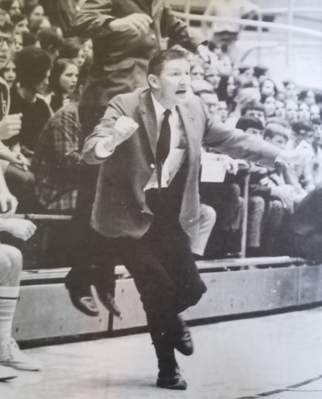

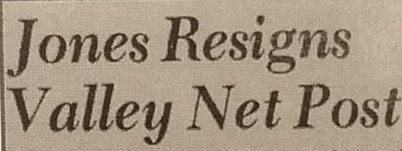

In late June of 1973, Coach Jones stunned the Springs Valley High School community by announcing his resignation from the head basketball coaching position. While Larry Bird and the rest of the team found the news shocking, being unsure of what their new coach would be like, the rest of the world took little notice. Jones remained, however, as the school’s athletic director. Meanwhile, the Bedford newspaper sport page did not even mention Larry’s presence when talking about the Blackhawks upcoming season, saying that the school’s new coach, Gary Holland, would need a few games to figure out his starters and that the team faced “a rough schedule.”

Perhaps the greatest sign to me that the entire world was oblivious to what was about to happen was Coach Jim Jones’ surprising resignation. Obviously, he would not have missed the ride Larry was about to take the team on if he had known. Even new coach Gary Holland was clearly unaware of what was about to happen, as were the Blackhawk fans, Holland later telling a Louisville Courier Journal sports reporter, “I had people telling me at the beginning of the season that we’d be lucky to break even. I studied the schedule and figured we’d win 14.”

Larry Bird had done his part preparing for the upcoming season, working harder than ever during the summer. But the biggest factor impacting Larry’s play took place without any effort from Bird.

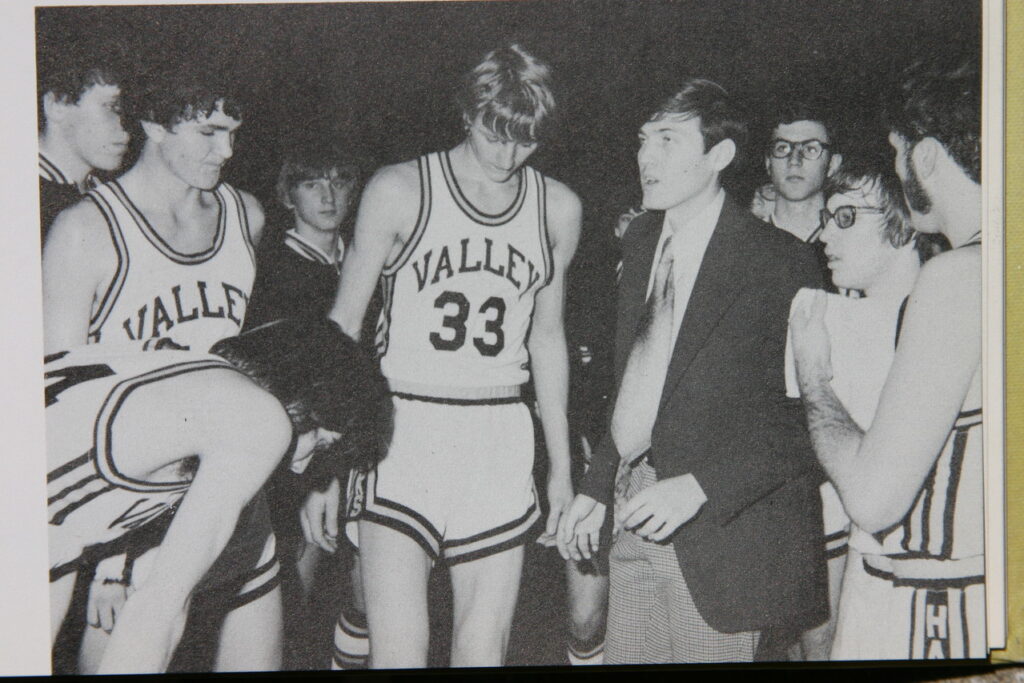

Larry was only 6-3 when school let out at the end of his junior year. When he came back to school in the fall of 1973, he was four inches taller. Even the coaching staff was astounded when they measured him, realizing he had literately grown right before their eyes in a three-month period. Coach Holland recalled realizing during the mid-summer that Larry was the same height as 6-5 former player Steve Land, but thought “Larry’s hair made the difference, but even when he got a haircut, he was still right up there.”

Just as amazingly, even though Larry was now 6-7, he could still deftly handle the ball, as well as pass and shoot as well as he had when he was 6-3. Bird had also put on some needed weight, adding 40-50 pounds to his thin frame from the year before and was now at 185 pounds. Dedicating himself to a weightlifting program the summer before the season started brought added strength, making him strong enough to push opponents around under the basket.

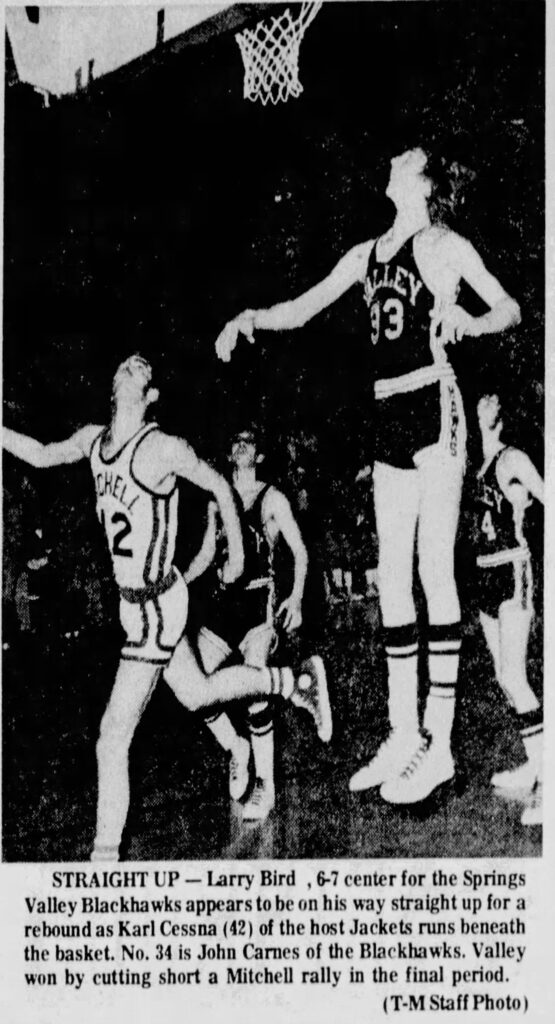

The team’s first game showed great promise. The Blackhawks scored just short of one hundred points, this in an era before the three-point line, and beat Pekin Eastern 95-71. Although he had 27 points, Larry was still not the leading scorer for either team, but a Bedford sports reporter did catch three other new eye-popping dimensions about Bird’s play—Larry’s 21 rebounds, 7 scoring assists, and several blocked shots.

After the Pekin Eastern game, things got rocky. Valley played a much bigger school, Washington, at Springs Valley in their second contest of the season. The Hatchets won in a double overtime, with Bird scoring 27 points for the second game in a row from almost every spot on the floor. He was also deadly on free-throws, hitting 13 out of 14 charity tosses.

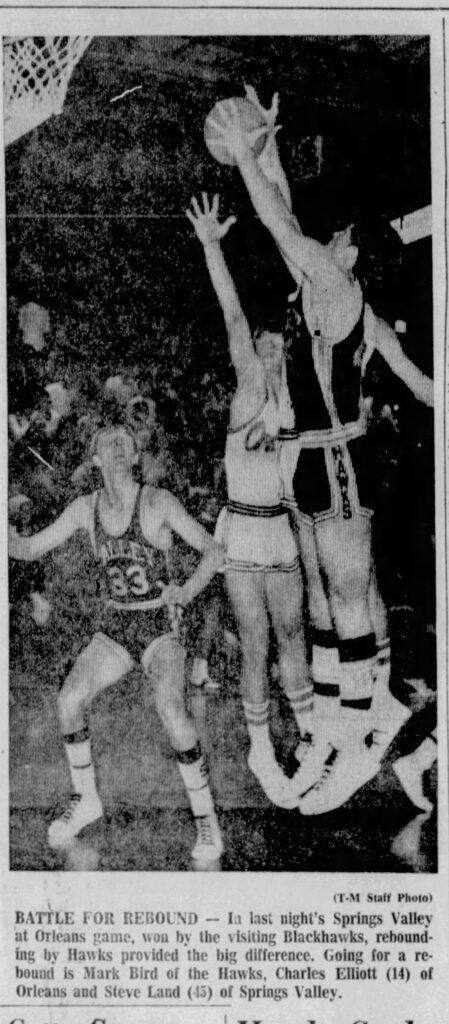

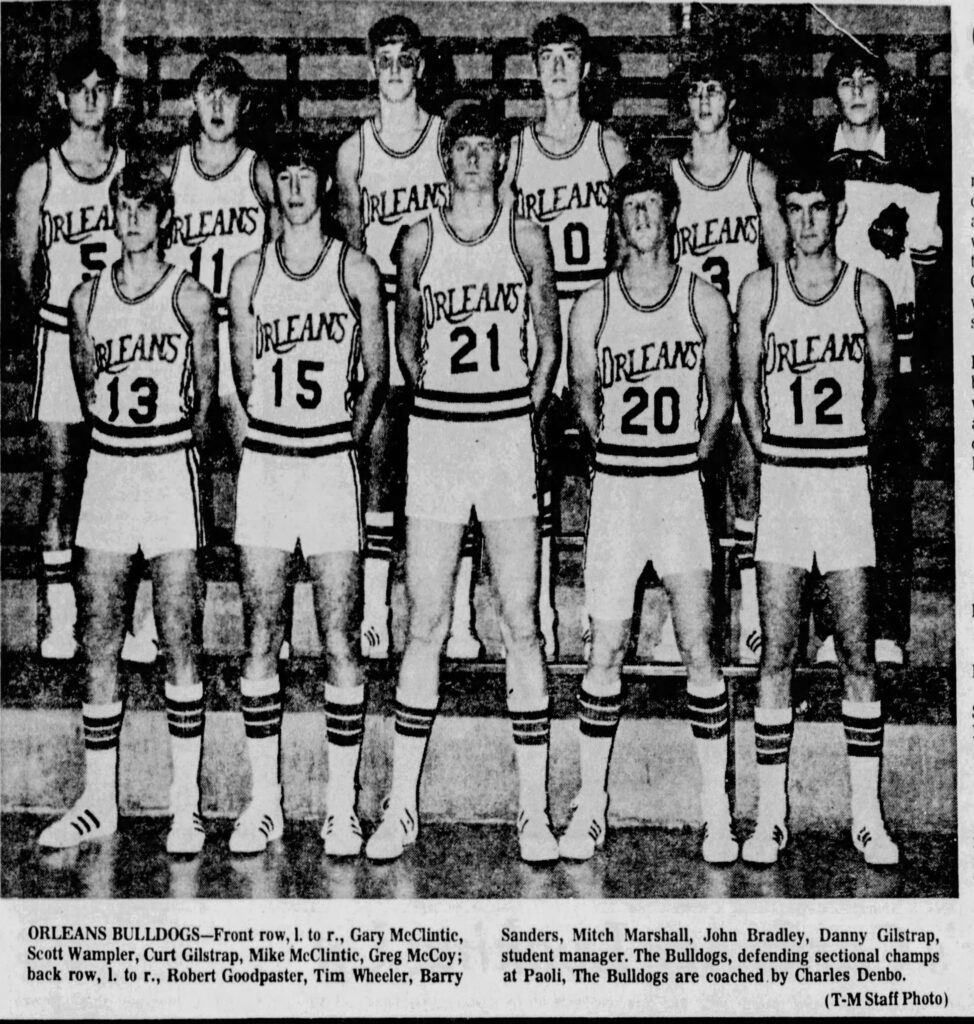

The third game of the season was against another tough opponent, the Orleans Bull Dogs, a team who had its own formidable big man, Curt Gilstrap. Curt stood 6-7 and weighted two hundred pounds. He would initially attend the University of Louisville on a basketball scholarship but later transferred to Oakland City College, Mark Bird’s college team, where he became one of the school’s best all-time players.

Orleans, with Gilstrap leading the charge, had knocked the Blackhawks out of the sectional tourney the year before and Valley was out for revenge. Bird broke Steve Land’s single game scoring record that night against the Bull Dogs, knocking down 43 points, but Orleans won the game, with Gilstrap getting 31 tallies before fouling out.

While the loss to Orleans was a bitter one, Bird later recalled that he suddenly felt like he could score at will after that game. One of his fellow players remembered, “I never saw him play like that. It was it was like a magic wand had touched him.”

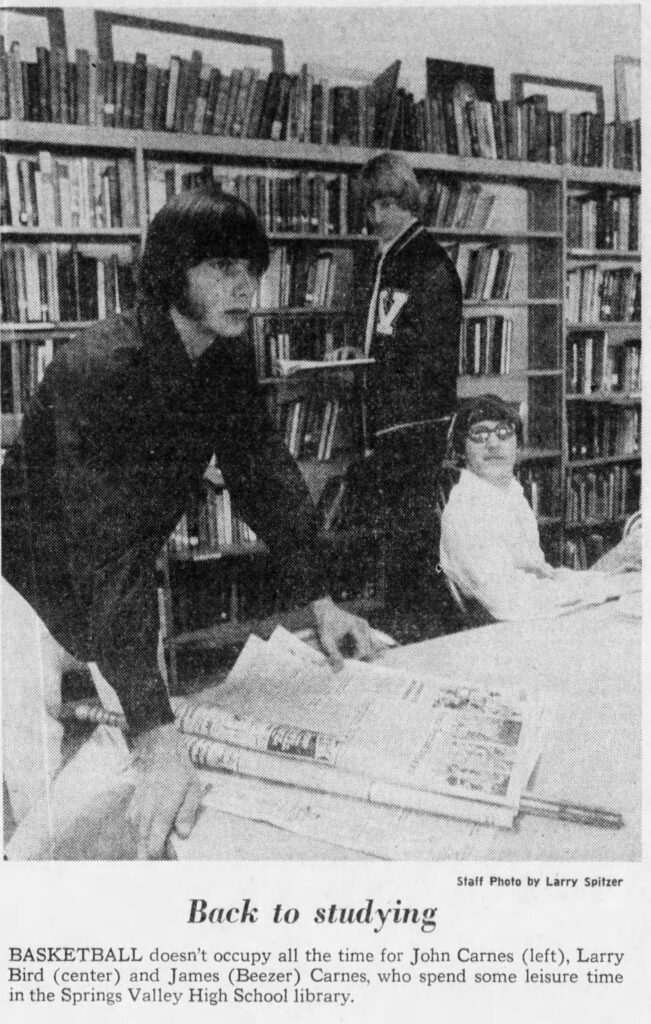

In the next game, the Blackhawks easily dispatched North Daviess 94-72, with Bird racking up 26 points. The game also demonstrated Larry’s habit of sharing the scoring, with James Carnes getting 25 points and John Carnes and Doug Conrad racking up 14 and 13 points respectively.

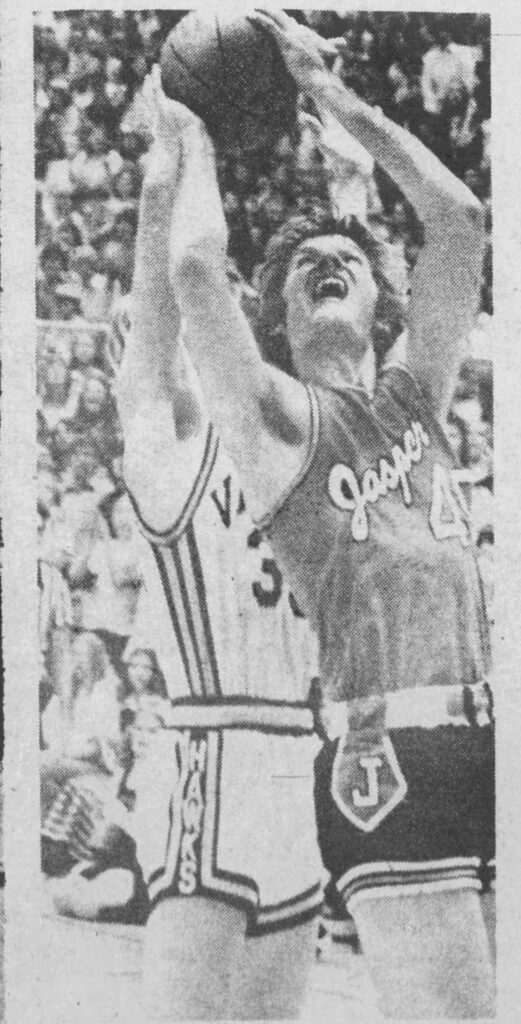

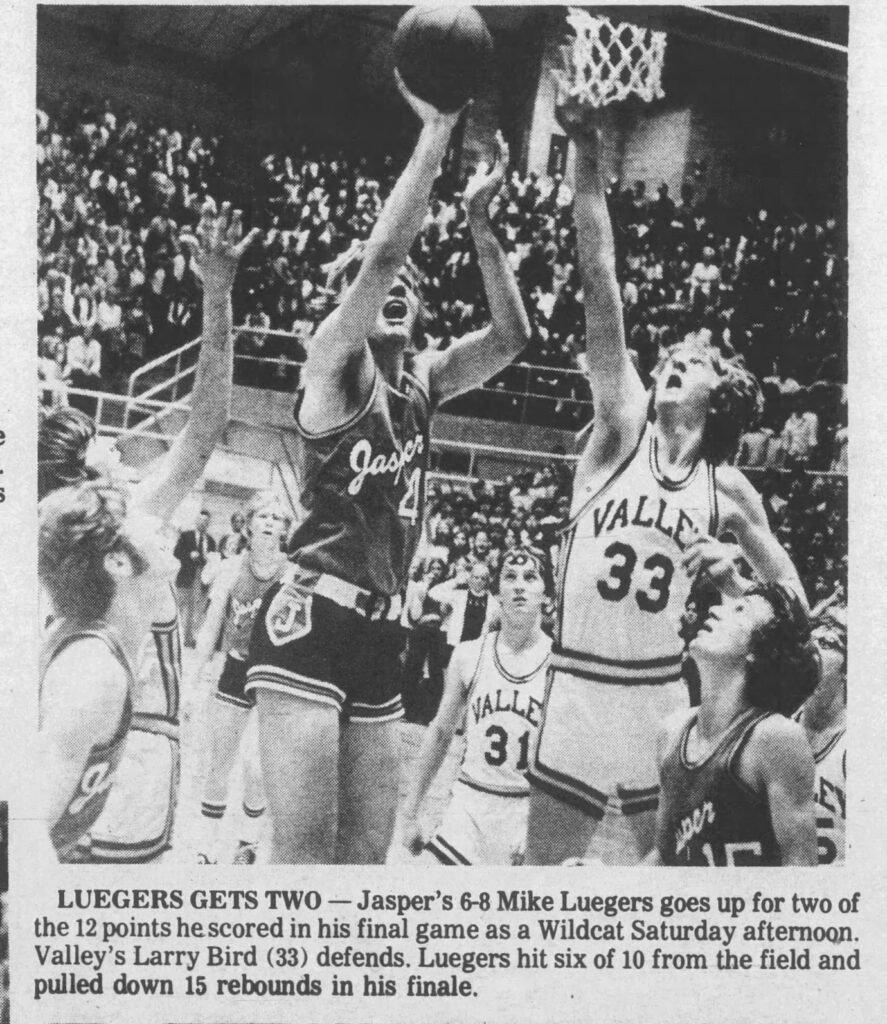

The win over North Daviess left Valley with a 2-2 record and framed the upcoming clash with the state ranked Jasper Wildcats, a team that had gone to the sweet sixteen level of tournament play in the last two seasons and who touted another big man Bird would have to battle, 6-8 Mike Luegers. This would be Larry Bird’s game, however, the first one that put him in the spotlight of sports reporters, especially the colorful Jerry Birge at the Jasper Herald.

Birge, like the great sports writers of that era, loved to frame a good game around drama, especially when it involved super effort on the part of a team or a player. He also did not hesitate to critique the hometown Jasper Wildcat team when he thought it was needed. Like all good newspaper writers, he knew the key to a readable article was controversy. Best of all, Birge was quick with catchy, potent headlines.

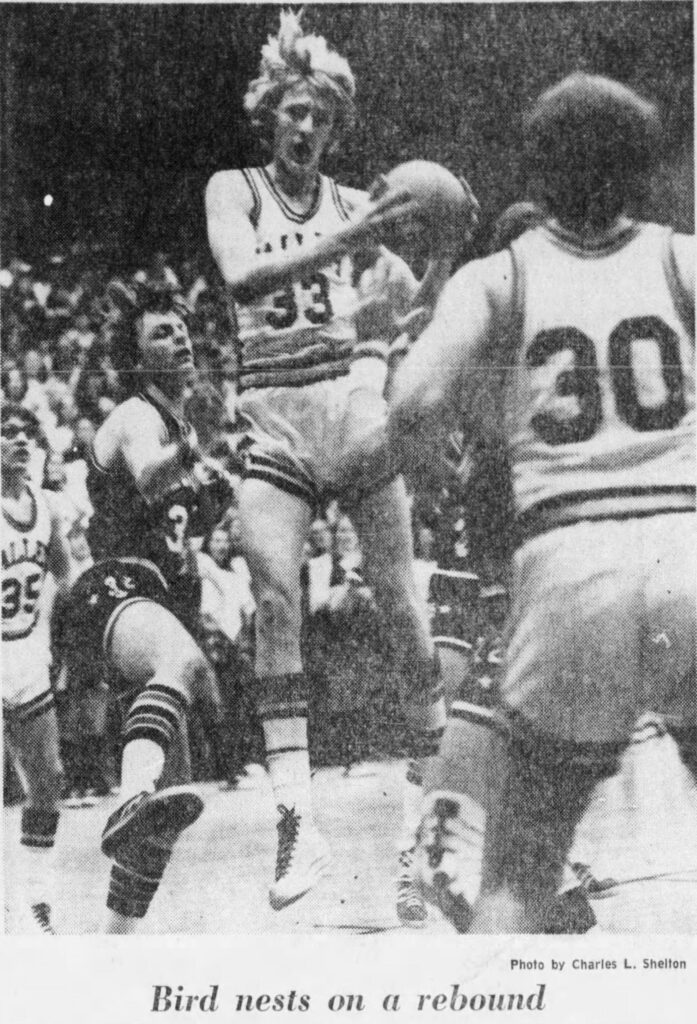

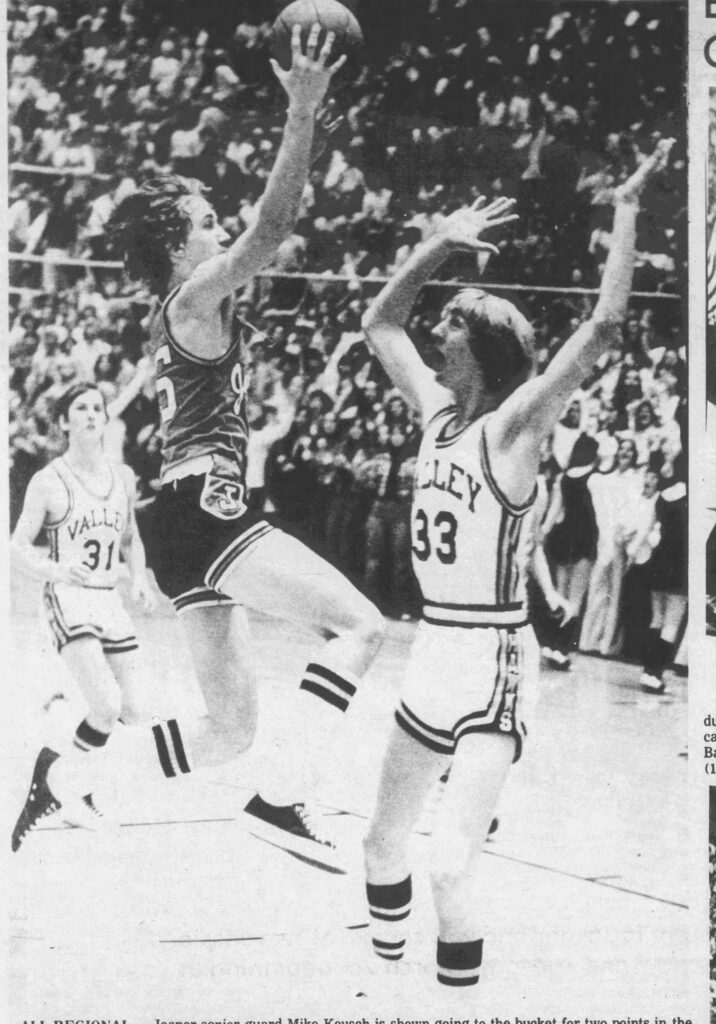

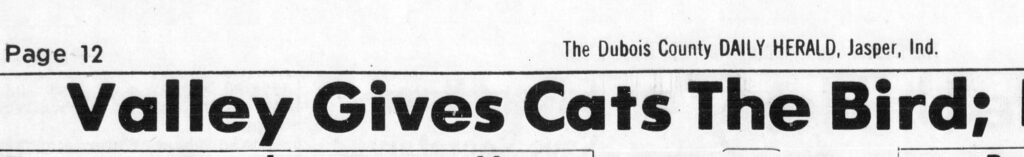

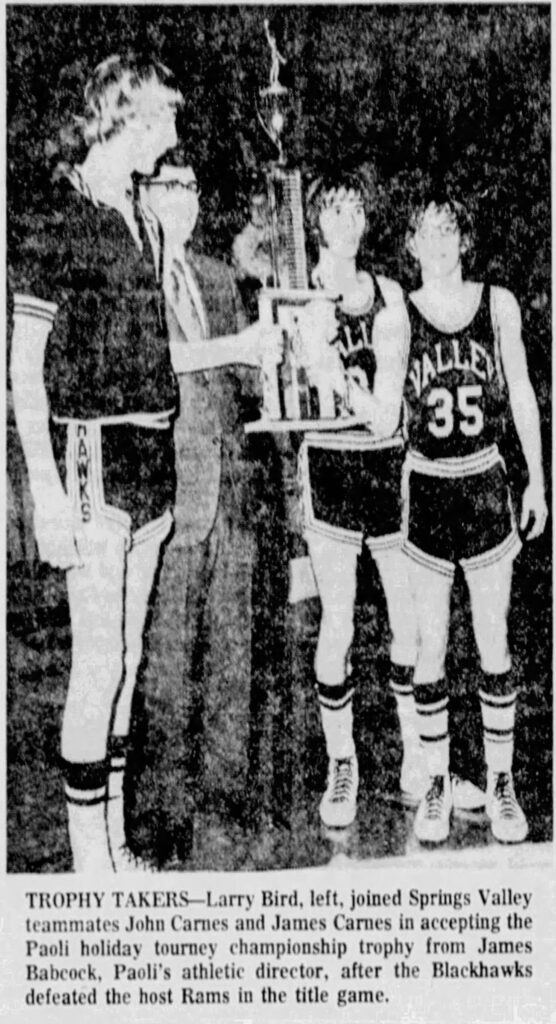

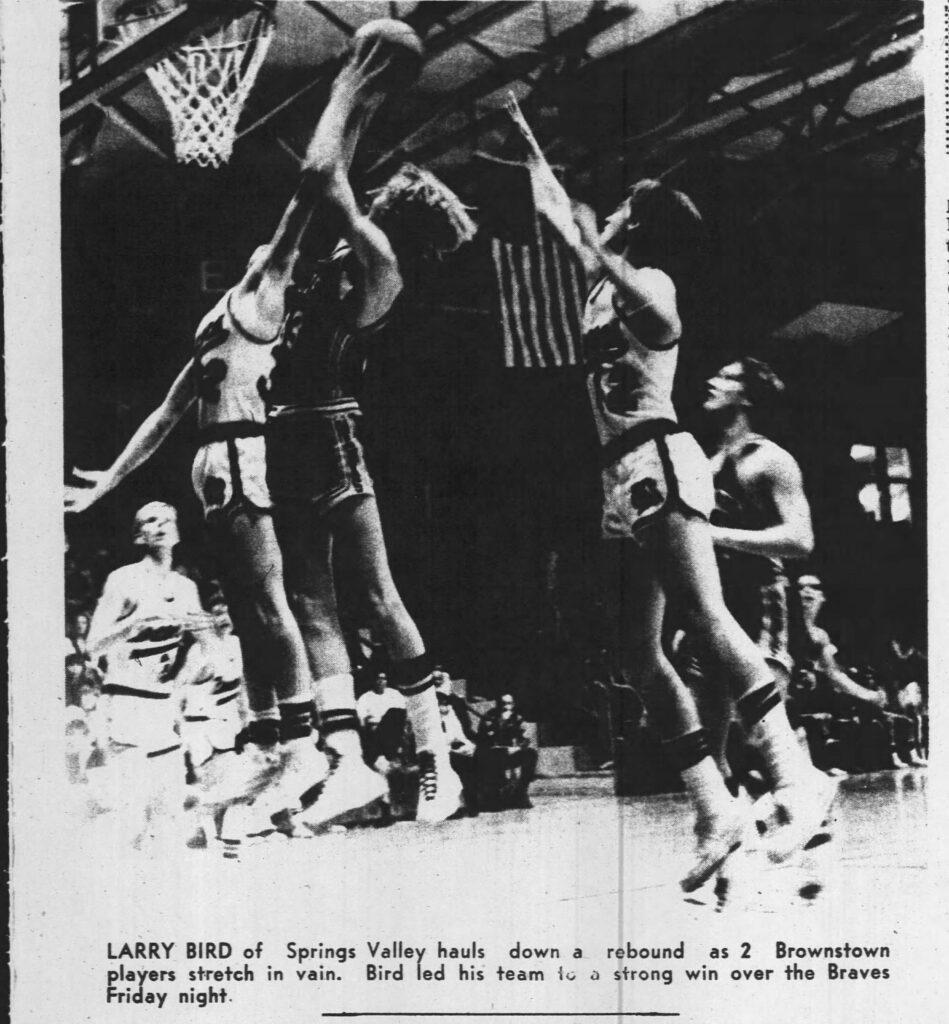

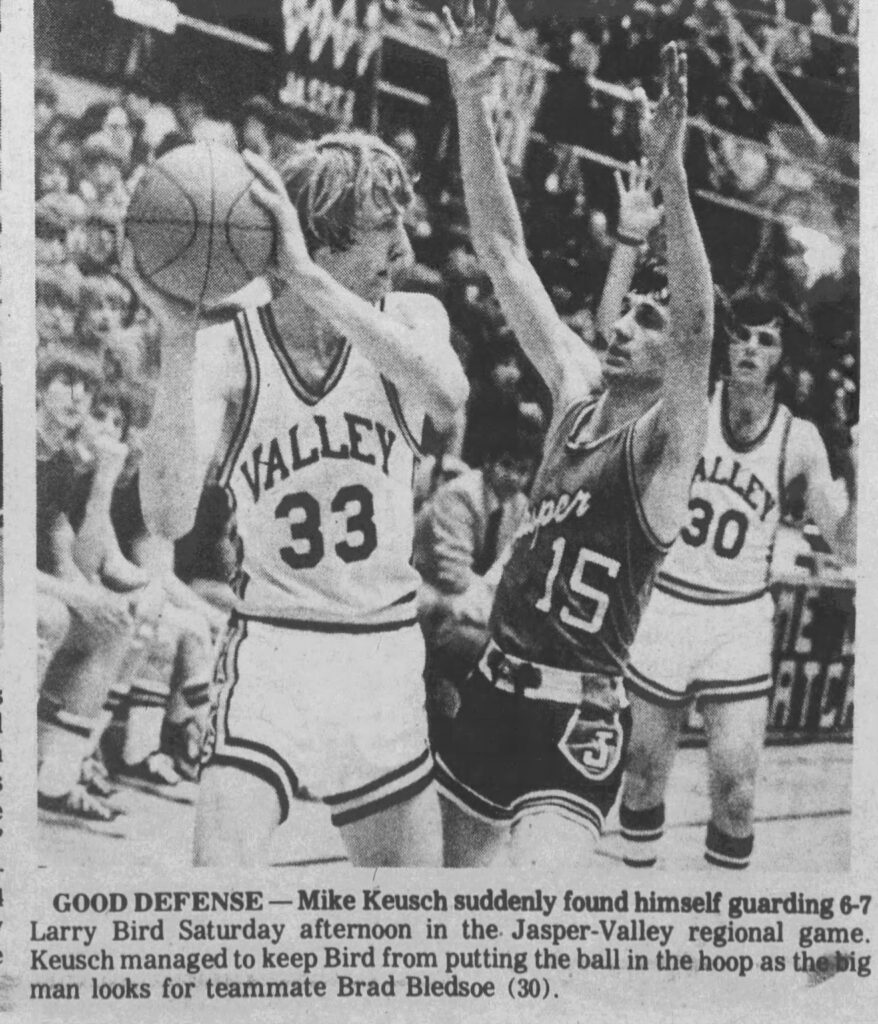

After Valley stunned the Jasper team with a real drubbing, Birge’s sports column the next day headlined, “Valley Gives Cats the Bird.” Larry “was the big show,” Birge reported, “although he had plenty of support. He finished with 30 points for the night, 14 of 22 from the field and hauled down 18 rebounds.” Bird also held big Mike Luegers to six rebounds, although Mike was the leading scorer for the Cats with 21 points. Luegers, a proud player, would later get a semblance of revenge in regional play, however.

Bedford sportswriter Al Brewster also playfully used Larry Bird’s name in his headline about the Jasper game, writing, “Springs Valley Bird Flying High.” Brewster reported,

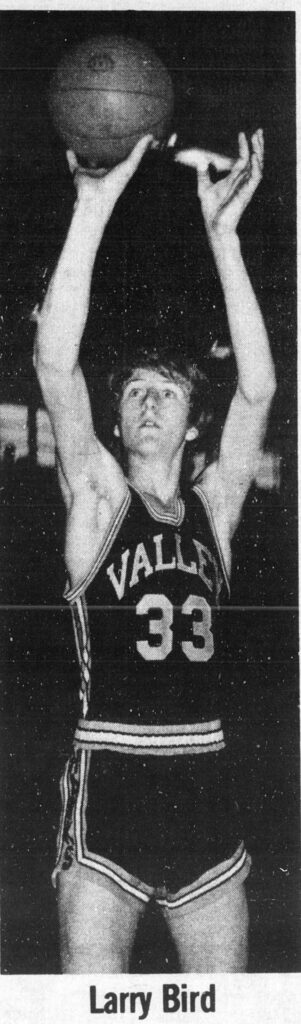

Bird, who is 6-7, 180-pound senior, has a 30.7 scoring average this season and the Hawks have a 3-2 record. His rebound average is 18 a game to go with five assists. In the recent Orleans game he scored 43 points for a new school record. College scouts wouldn’t be wasting their time by keeping a close watch on Bird. He’s going strong this season and is capable of playing either center, forward or guard.

A larger urban newspaper in the region also got wind of Springs Valley’s surprise victory over Jasper. Sportswriter Dave Koerner, of the Louisville Courier Journal, visited French Lick and interviewed Coach Holland about the team and its rising star. His headline also played on the Bird name—“Bird flyin’ high at Springs Valley with added muscle.” Holland told the sportswriter, “Bird has a great outside touch and can take the center outside and really score on him.” What really caught Coach Holland’s attention, however, was Bird’s defensive play. “He’s our best defensive player. He’s averaging five blocked shots a game and is a real intimidator.”

After the Jasper game, the Blackhawks and Larry Bird went on a terrific tear. They avenged their previous loss to Orleans, whipping the Bulldogs at the Paoli Holiday Tournament 84-68. Orleans had an undefeated record before Larry tossed in 38 points and pulled down an incredible 21 rebounds against big Curt Gilstrap. Curt tallied 31 points in a losing cause.

Bird’s next game, after the big wins at the holiday tourney, was at nearby Shoals, and in attendance was none other than Indiana University coach Bob Knight, showing up to see if what he had been hearing was true. The Vincennes Sun-Commercial reported, “Indiana University Coach Bob Knight attended the Springs Valley-Shoals game Friday night for the purpose of inspecting Bird in action.” Apparently, he liked what he saw. He came to more of Bird’s games, contests where Larry seemed to rise to a higher level with each game.

Oddly, newspapers outside of the southern Indiana region hardly noticed Larry Bird. The Indianapolis Star, in Bob Williams’ sport page column “Shootin’ the Stars,” mentioned Bird and Curt Gilstrap briefly in early January of 1974, quoting a down-state coach who believed, “Both should play college ball somewhere.” Bird’s lack of coverage in the rest of the state, however, was balanced out by Jasper’s Jerry Birge, who became Larry’s biggest fan among the newspaper sports writers in southern Indiana by the middle of the 73-74 season. In his column, “Keeping Score,” under the title High Flying Blackhawk, Birge wrote a super write up in mid-January about Larry.

The Blackhawks steamrolled over West Washington (98-45) and Corydon (99-73) this past weekend and in the process, the high-flying Bird left the nets limp in the West Washington and Springs Valley gyms. They were still smoking yesterday morning after Bird touched them for 42 points Friday night (at West Washington) and an incredible 55 points Saturday night at Valley. In that Saturday night display of offensive talent, Bird tossed in 22 of 33 field goal attempts, one of the finest shooting exhibitions ever staged in Indiana basketball. . . . In that game against Corydon Bird showed his talent in other areas. In addition to hitting 22 of 33 from the field, he dropped in 11 of 17 free throws, pulled down 24 rebounds, and was credited with five assists. . . . Statics tell the true story about Larry Bird. In addition to his 33.6 scoring, the big Blackhawk has avenged 20 rebounds a game, six blocked shots per game on defense and an outstanding four assists per game. . .. Because of his sudden surge into the spotlight, the young (17 years old this past December 6) Blackhawk ace has brought college scouts from all parts of the country. And they like what they see. A complete ballplayer with his inside-outside shooting ability, his outstanding rebounding work, defensive play, and passing.

It was not only the 55 points at the Corydon game that Bird would be remembered for. He also made a flick pass in the game, a crowd-pleasing type of pass he would be noted for in the pros, for the first time. Going out of bounds as he chased a ball, he reached behind his back and flicked the ball so that it went into the hands of another team player who was rushing for the basket.

In a Louisville Courier Journal article shortly after the game, the disappointed Corydon coach noted, “He plays more like a guard. He’s very dangerous for a couple of reasons, the shooting range he has and his ability to go with the ball. He has all the attributes of a guard. He can shoot from the bleachers, or he can take the ball from 25 feet out and with a fake or two can go in like a guard.”

Few if any of the area’s high school coaches had seen such a player before. The best game of Bird’s breakout season, the one most remembered from that year, however, was yet to come, a contest of epic proportion between Springs Valley and conference rival Loogootee at the Blackhawk’s gym, and I would be there.

_______________________________________________________

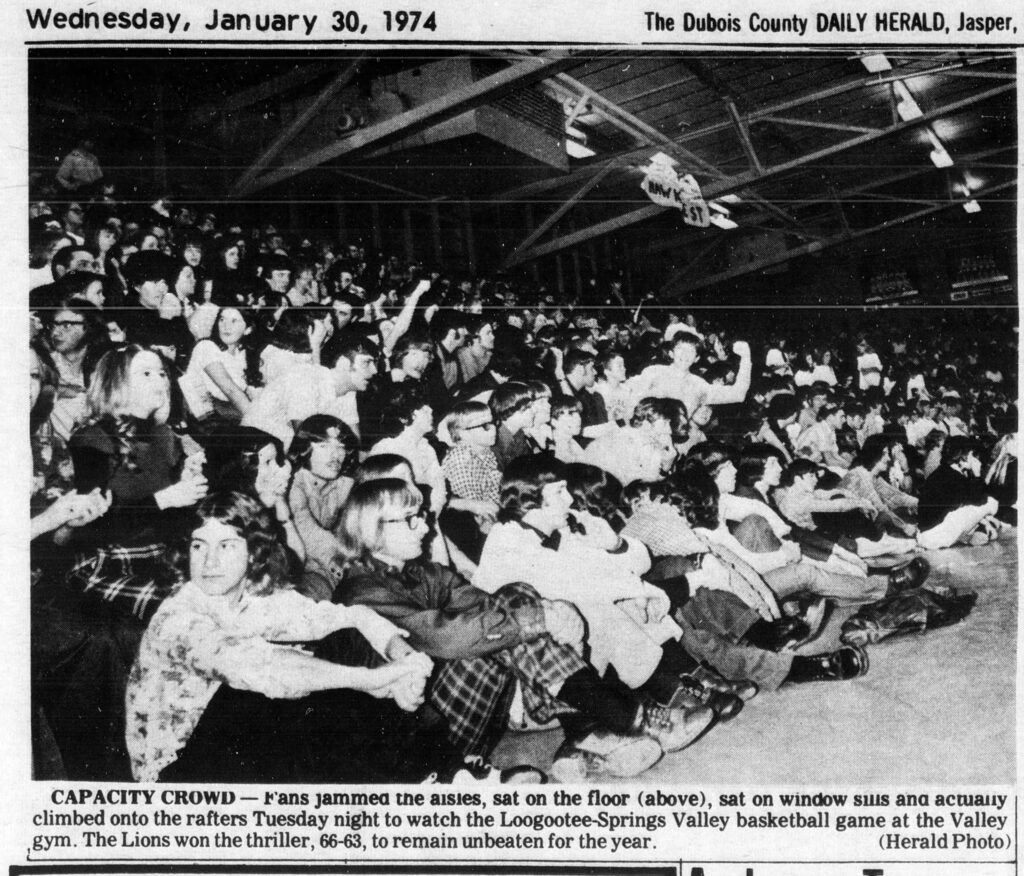

The Loogootee/Spring Valley regular season showdown on January 29, 1974, is mentioned in all of the biographies of Larry Bird. At this point, Valley was on a roll, with a nine-game win streak, while Loogootee was undefeated and held a high state ranking. The game was juiced up even more since Loogootee had surprised the Blackhawks the year before in a stunning upset during the regular season, and the winner of the 1974 game would probably end up as the conference champs.

Loogootee would be a true test as to just how good Valley and Bird really were. In his autobiography, Bird recalled, “We were playing well, and Loogootee High came into our gym for what they were saying was the biggest regular season game we’d had in ten or fifteen years.”

Coach Holland was interviewed by Courier Journal sportswriter Russ Brown on the eve of the critical game, Holland explaining to the reporter that his team was at top form and that the Blackhawks were playing well together, and added, “We’ve gotten consistent play from Larry in the middle. Everyone else has contributed, of course, but Larry’s steady performance is what has kept us going.”

Holland was perhaps understating the support of the other players, two of whom, John Carnes and James Carnes, were averaging well into double figures. Still, it had to be scary when other teams saw a 6-7 player like Bird suddenly take charge of a game the way a quick, well-passing little guard could, not only with dead-eye shooting, but with skilled dribbling and pinpoint passing. The Blackhawks were averaging a rip-roaring 86 points a game on the eve of their contest with Loogootee and possessed a solid 10-2 record. Larry was averaging 33 points a game and was the leading scorer in the state.

Loogootee was not a tall team, their loftiest player being 6-3 portly center Mike Walls. On offense, however, the Lions had two outstanding guards, senior Alan Crane, who was avenging 15 points a game and Coach Butcher’s son, junior Bill Butcher, who averaged 20 points. Rugged playing Wayne Flick, who had talked to my dad the day I took my father to see my new classroom, and muscular Mike Mattingly rounded out the starting five.

Butcher’s team rarely made mistakes and played superb defense. The team averaged 67 points a game but had the best defensive average in the state, holding opposing teams to an average of less than 50 points. They simply picked teams apart with their constant full floor passing, always taking the high percentage shot.

An intangible factor for the game had nothing to do with a player, but rather involved the coaching skills of Loogootee’s Jack Butcher. In the basketball-crazy state of Indiana, high school coach Butcher may have been the best. In seventeen years at tiny Loogootee, he had sixteen winning seasons and a winning percentage of just under eighty percent. His teams had won eight sectionals, two regionals, and one semi-state.

One can easily image too novice Coach Holland savoring the possibility of beating the great Jack Butcher in their first meeting.

________________________________________________________

I rode to the game from Jasper to French Lick with Erma and Lee Kavanagh, Lee giving me expert context to the game during the entire ride. The drive was pleasant, with hilly landscapes flashing by the car windows on the curvy roads until the waning light morphed the hills into something a bit more sinister in the gathering darkness.

As we parked, Lee said, “Be ready for a crowd like you’ve never seen before and plenty of big-name college coaches.” He was on the mark on both counts.

My strongest recollections of that game forty-seven years later was how warm it was in the gym before the game even started, the heat a product of both the unusually high temperature outside that evening and the estimated 4,000 people who had somehow been shoehorned into a gym made to seat 2,700.

People were sitting on others’ laps in many instances, and the crowd noise was deafening.

I’m not sure where Bob Knight sat that evening among the crowded spectators. Knowing of his reputation for edginess, I feel sorry for anyone who might have gotten on his nerves. Likely, however, he would have been distracted by what he saw that night.

Jasper Herald sportswriter, Jerry Birge, under the heading, “Standing Room Only” rendered a colorful introduction to his blow-by-blow account of the game in the paper’s next day’s sports page.

A circus-like atmosphere filled the air Tuesday night as a Springs Valley record crowd jammed into the Springs Valley gym for the high school basketball clash between the host Blackhawks and the undefeated Loogootee Lions. The big crowd was lined three-to-four persons deep in the area behind the 2,700 seats in the Valley gym. All the seats were filled before halftime of the junior varsity game. . .. The varsity game developed into the Indiana basketball classic expected.

Mike Walls, Loogootee’s 6-3 center had the impossible task of guarding Bird, but Jack Butcher wisely assigned gritty Wayne Flick to front Bird, the duo effectively keeping Larry from going inside. Bird, however, just went way out on the floor and made several beautiful jump shots from the corners that took my breath away.

Unfortunately for Valley, Alan Crane and Bill Butcher had hot hands too, letting go of long bombs with perfect confidence. The contest unfolded in a deliberate fashion, like a tense chess game, each player moving with confidence and purpose and with few mistakes being made. The fans were constantly on their feet. It was a war of back-and-forth jump shots, most of them at what would have been three point range in this day.

At the end of the first quarter, Loogootee led 18-14, and by the half, the hot shooting of Bill Butcher had put the Lions up by five, 32-27. In the third quarter, Valley finally took the lead, 33-32, with five and a half minutes left in the quarter and led 44-42 when the quarter ended.

No more than four points would separate the two teams the rest of the way.

I can still hear the famous Loogootee cheer shouted out many times that night—“L-o-o-G-o-o-T-e-e, go, fight, win- go, fight, win- go, fight, win!”

Several impacting events occurred in the third quarter. Bill Butcher’s shooting went cold, probably from his being fatigued. He made only one of six attempts. This allowed Valley to chip away at what had been a five-point half-time lead, to go ahead of the Lions. Jerry Birge mentioned two other happenings, however, that worked against Valley.

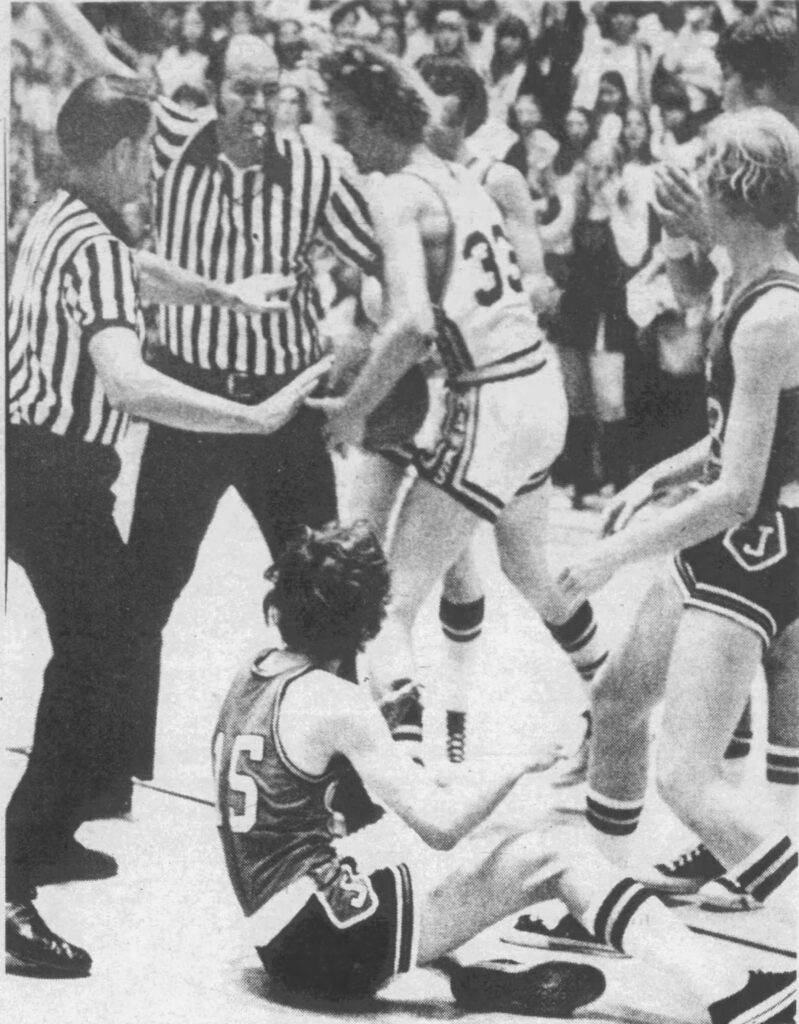

With 2:55 remaining in the third quarter the Hawks controlled a jump ball at the Loogootee free throw circle. Bird took the tip and went immediately to score—in the Loogootee basket! The “wrong way” move by Bird was nullified, however, as he was called for traveling just before he made the basket. Valley was fortunate the basket didn’t count, but it did give the ball back to Loogootee after the Hawks had controlled the tip. A much bigger play occurred with only 10 seconds left in the third quarter. Bird caught a perfectly placed elbow in the third quarter on a rebound battle and sagged to the floor in pain. The injury led to a Valley timeout with only 10 seconds on the clock in the third quarter, a precious timeout when one notes that the lack of a time out with seven seconds remaining in the game was the most critical play of the evening.

Bird would certainly do his part, as Birge also noted, Larry often going “to the corners to drill 25-footers. He led fast breaks, worked the boards effectively, fed his team-mates with pinpoint accuracy and turned in a steady performance even though Loogootee did a good job keeping him away from the basket and away from the ball.”

What Bird and company failed to do was stop Bill Butcher.

Butcher turned hot again in the final quarter, popping in six out of seven shots, his last basket with 31 seconds remaining, driving “to the baseline and putting up a 15-foot jumper that bounced off the back of the rim and dropped through the basket.” The goal put Loogootee up 64-63.

After Butcher’s basket, Valley still had time to pull out the win. John Carnes missed a shot and then Alan Crane was fouled. Crane missed the first of a one-and-one attempt and in the fight for the rebound, the ball went to Valley with nine seconds left. When Valley threw the ball into play, Jim Carnes, surrounded by Loogootee players, was unable to get the ball to another Valley man. In panic, he called a time out, not realizing that his team had no more time outs to use, having spent one when Bird was hurt in the third quarter. The referee quickly called a technical foul.

Bill Butcher missed the technical shot, but on the inbounds play, Crane was fouled and hit both shots for the final score of 66-63.

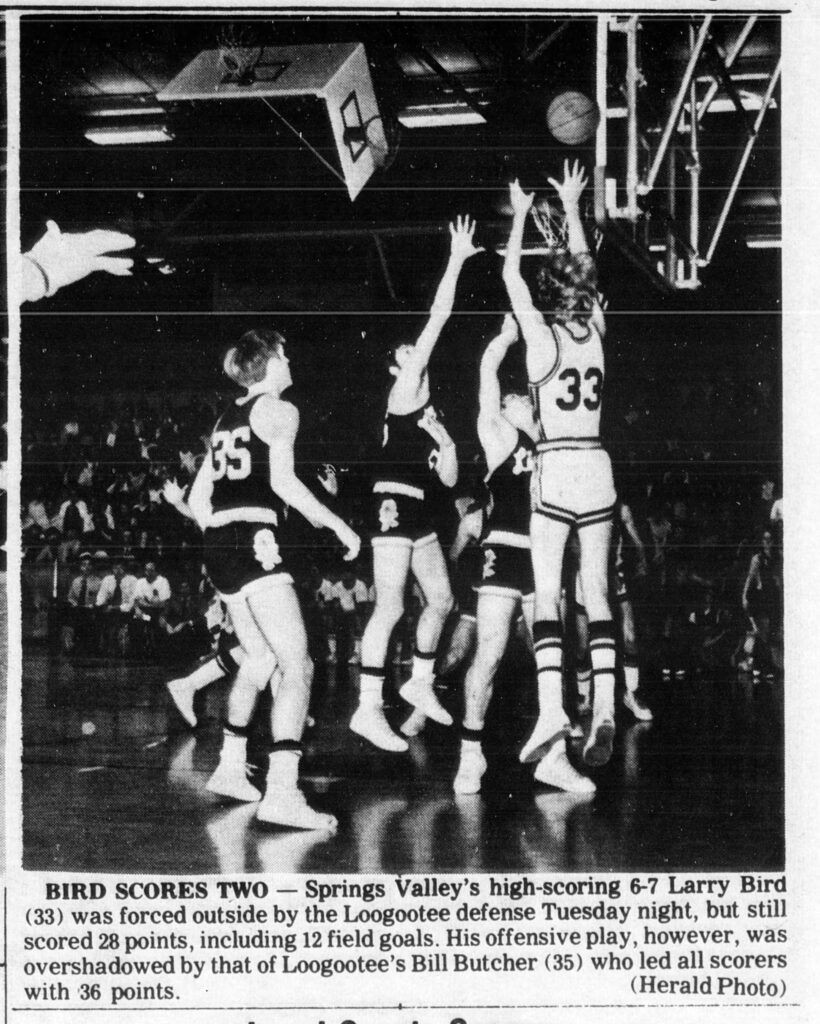

The next day Russ Brown of the Courier Journal wrote this sports headline, Bill Butcher puts ax to Springs Valley. Coach Holland explained in the article what he thought happened. “We just couldn’t stop Butcher. His range is too good and one of our guards was too little and the other too slow. We just had to hope he missed.” While Larry Bird had tallied a respectable 28 points, Butcher had garnered 36. As Jerry Birge put it in the Jasper newspaper, “Bird was rating the headlines before the game, but those headlines belonged to Loogootee’s Bill Butcher Wednesday morning.”

The unsung hero of the game was probably Loogootee’s Wayne Flick. Russ Brown reported how “Bird was having trouble trying to shake free of Loogootee forward Wayne Flick. He began guarding Bird, whose average was 34 points, after the Valley senior had scored 10 in the first quarter.” After Flick started to guard Larry, Bird made only four points in the second quarter and fourteen in the second half. Coach Butcher explained, “We were trying to front Bird with Flick and jam him some from behind. I’ve seen other teams try that and fail, but we seemed to be pretty successful.”

Perhaps Jerry Birge summed up the epic basketball clash best when he wrote in the Herald, “Bill Butcher and Larry Bird treated the overflow crowd to a pair of great individual basketball performances. The two teams treated the fans to an exciting, close game the way Indiana cage fans love it. Loogootee fans were thrilled, and Valley fans were disappointed. But they got what they wanted to see: a whale of a basketball game.”

As for me, I called my dad as soon as I got home from the game. Before he could ask why I was calling so late, I said, “I just saw the greatest high school basketball game ever played.”

_____________________________________________________

The Springs Valley community was knocked low from the loss to Loogootee, especially given how the game ended. Up until the end, Valley fans probably carried the happy and exciting vision of the ball in the hands of Larry Bird and him releasing one of his beautiful arching shots from way out just as the final buzzer sounded. Most Loogootee fans were probably worrying about the same vision, although it would have been a nightmare to them.

Coach Holland took some pressure off Jim Carnes, the player who called the time out that probably lost Valley the game, explaining to a reporter, “Jim called the time out, but it was my fault. All week I harped at him that he was the one running the club. The kid did what I wanted him to do. I just forgot to tell him we didn’t have any more timeouts left. He’s really hurt about it, and I hope it doesn’t get him down much.”

Larry Bird, as usual, was all business, telling Carnes, “Don’t worry. We’ll get them next time.” Bird knew the two teams would likely meet again in the regional level of state tournament play in March.

The carryover from the Loogootee loss continued, however. Coach Holland had trouble eating and began to lose weight. He later told a Courier Journal sportswriter, “I noticed after the Loogootee game that I had to take up my belt a notch. When I first began losing weight, I thought something was the matter with me, but it all stemmed from nerves.” Holland also explained now he had begun worrying about even getting out of sectional play, where the Blackhawks would likely face Orleans again. He started thinking, “Are we going to be ready? Are we going to be healthy, are we going to shoot well? Things that aren’t coachable. You work hard all year, then it could all be shot in one night.”

Despite the coach’s worries, Valley breezed through all the rest their regular season games but two. At South Knox’s Bird’s long last second shot saved the game. Mitchell also gave Valley a scare before going down by two baskets. Oddly, the Loogootee loss did not slow Bird down one bit. He broke his own rebounding record twice and in his last home game collected 54 points, 38 rebounds, and made 8 assists. The Blackhawks ended the regular season at 16-3, winning one game less than the year before.

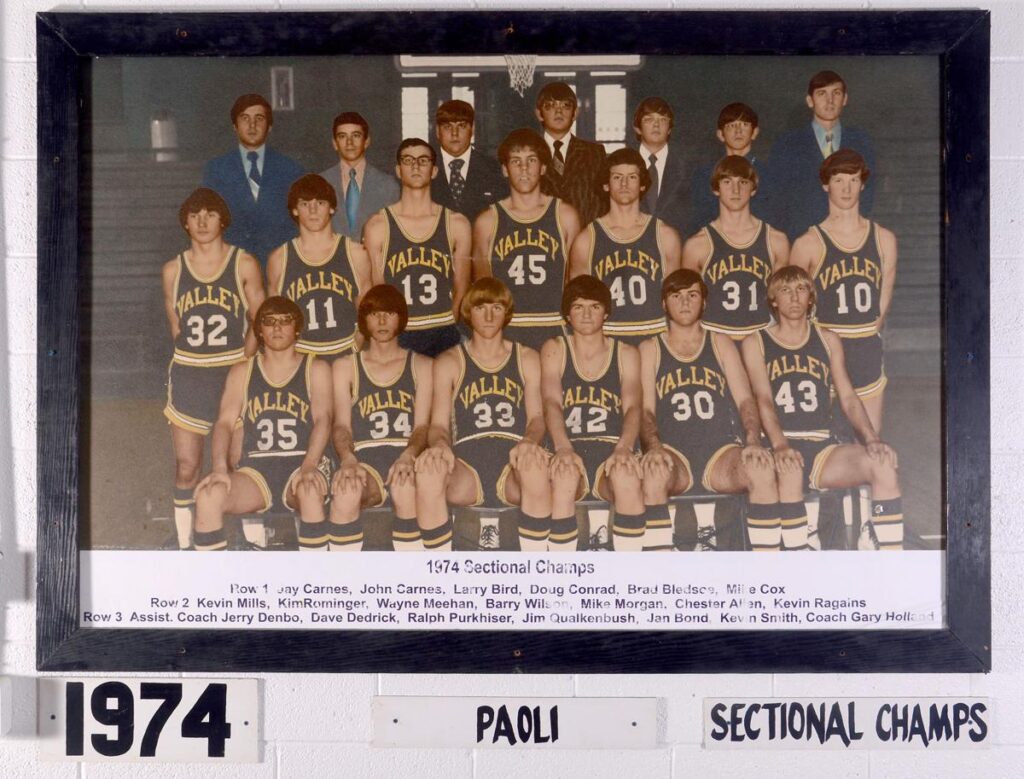

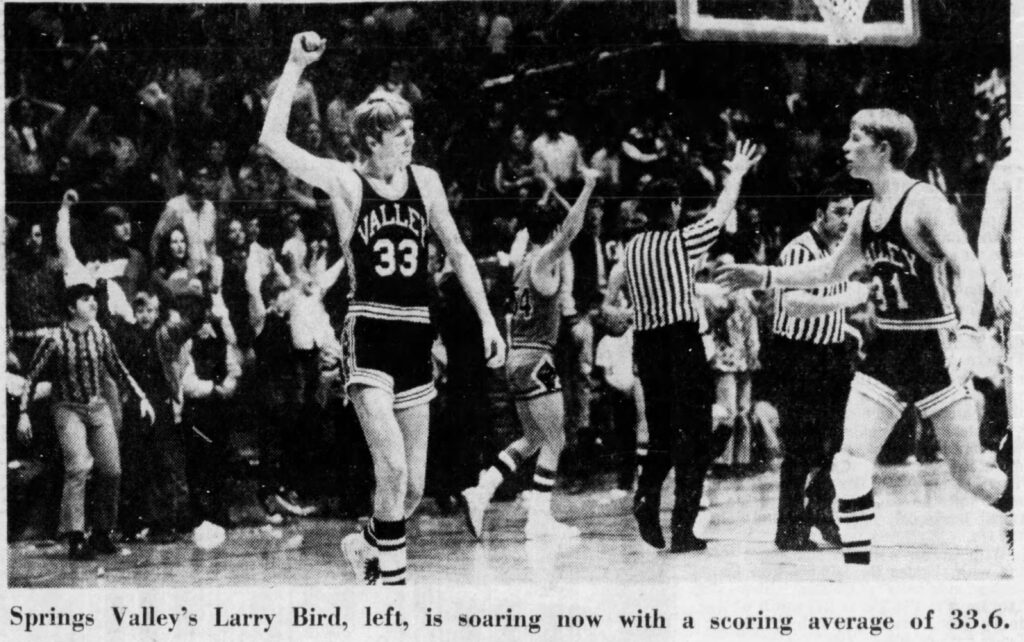

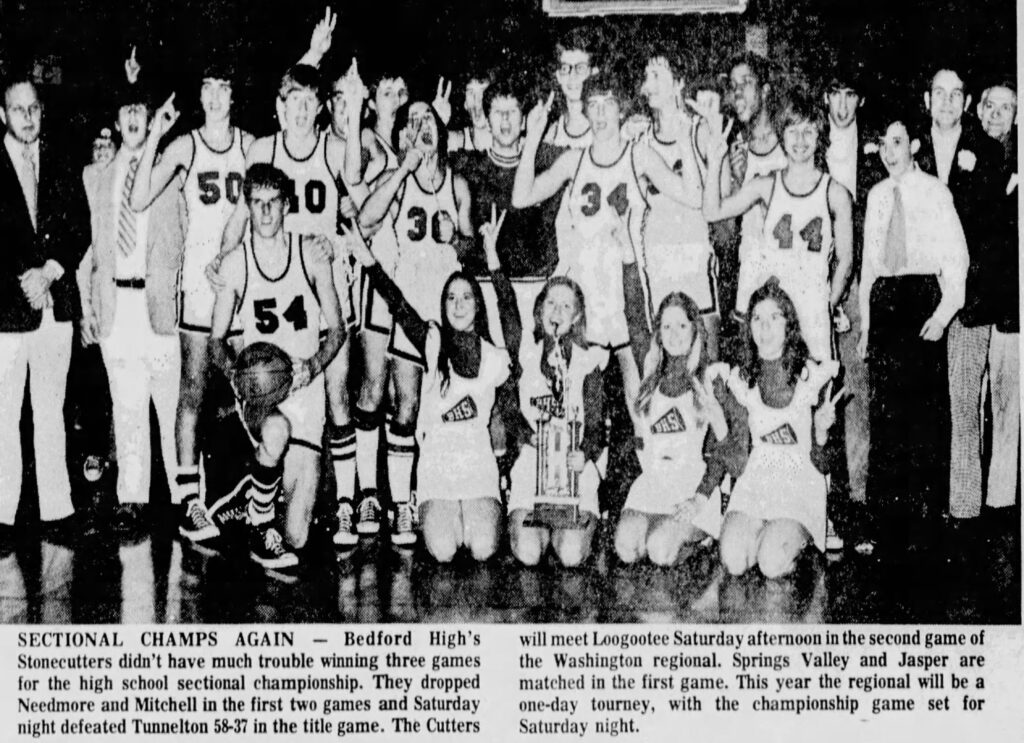

The sectional tourney at Paoli was anticlimactic. Springs Valley beat the host team for the third time that year in their first game 81-60. Meanwhile, Orleans, who had previously beat Valley once out of two games and had upset Loogootee on their home floor, was knocked out in a surprising turn-of-events loss to Milltown. Valley easily beat Leavenworth and then Milltown to win their first sectional tourney since Mark Bird had led the team to victory in 1971.

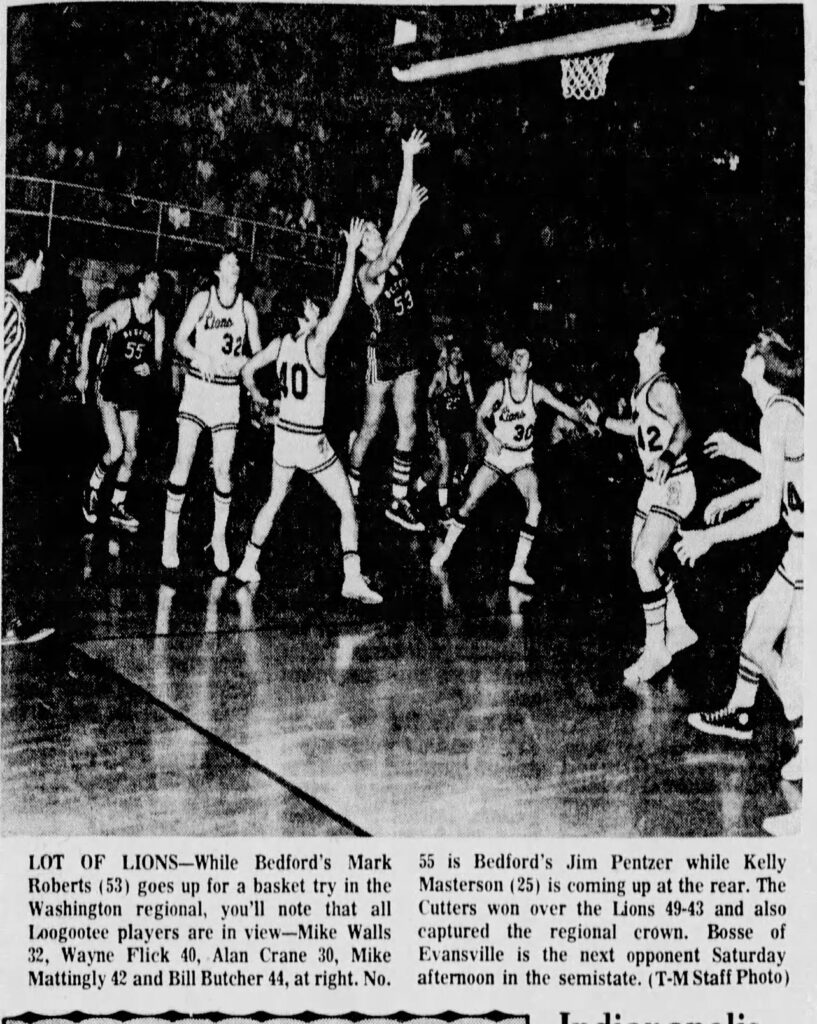

The Washington Regional, the next level of tournament played, feature two morning games, Springs Valley (20-3) going against Jasper (16-7), and the slightly favored Loogootee Lions (21-2) against the weakest team in the field, the Bedford Stonecutters (12-11). Bookmakers and sports writers probably found the regional difficult to call.

It was Lee Kavanagh who pointed out to me that Loogootee had easily defeated Bedford in the regular season while Valley had put Jasper away, but, of course, Valley had then been barely beaten by Loogootee. Loogootee, in turn, had lost to Curt Gilstrap’s Orleans Bulldogs at home in a game towards the end of the regular season, a team Valley split with in regular season play. Loogootee had also defeated Washington in the final game of that sectional site by two points, using the masterful delay game plan hatched by Jack Butcher. The Hatchets had defeated Valley in 2 overtimes earlier.

Lee’s explanation seemed complicated to me, but one thing was for sure, whatever the odds set by the bookmakers, the Blackhawks were dying to get at the Lions in the championship game. As for myself, I would attend all the Washington regional games that year, sitting with the Loogootee fans. I was also destined to have one more brief brush with Larry Bird.

___________________________________________________

Although he was from Jasper and wrote for the local paper there, sportswriter Jerry Birge had become Larry Bird’s greatest supporter among sports writers during the 1973-1974 season. He probably felt no disloyalty to his home team. Rather, he likely loved high school basketball when played by any team or player on a high level. Jerry was also frustrated by the lack of attention the rest of the state was giving to this spectacular player, being one of the very first to understand what Larry Bird was becoming.

Birge wrote on the cusp of the regional tournament’s opening that Valley was considered by many to be the favorite to win the Washington regional and to advance to the sweet-sixteen level of tourney play. Then he once more covered some old ground in describing Bird’s incredible play.

The talented Bird, naturally, is the key for the Blackhawks. The blond senior is avenging 31 points a game, has been over the 50-point mark on a couple of occasions, is an outstanding shooter both inside and out, dominates the boards every game he plays, blocks shots regularly with his intimidating defense and is a pinpoint passer, the leading assist man on the team.

Of course, the Jasper team would have something to say about this too.

I sat with the Loogootee crowd in the 7,000 seat Washington High School gym to watch the first game of the regional, Valley against Jasper. Every seat was filled, and there were college scouts galore there, and not only to see Bird. Jasper’s 6-8 Mike Luegers had broken his older brother’s all-time scoring record that season and was getting looks from several colleges. I am sure Loogootee’s Bill Butcher, while just a junior, was of interest too.

Once the game started, I found myself wishing Larry would get the ball every time. Whether he moved to one of the corners for a long jump shot, or made a move to the basket, he was a joy to watch.

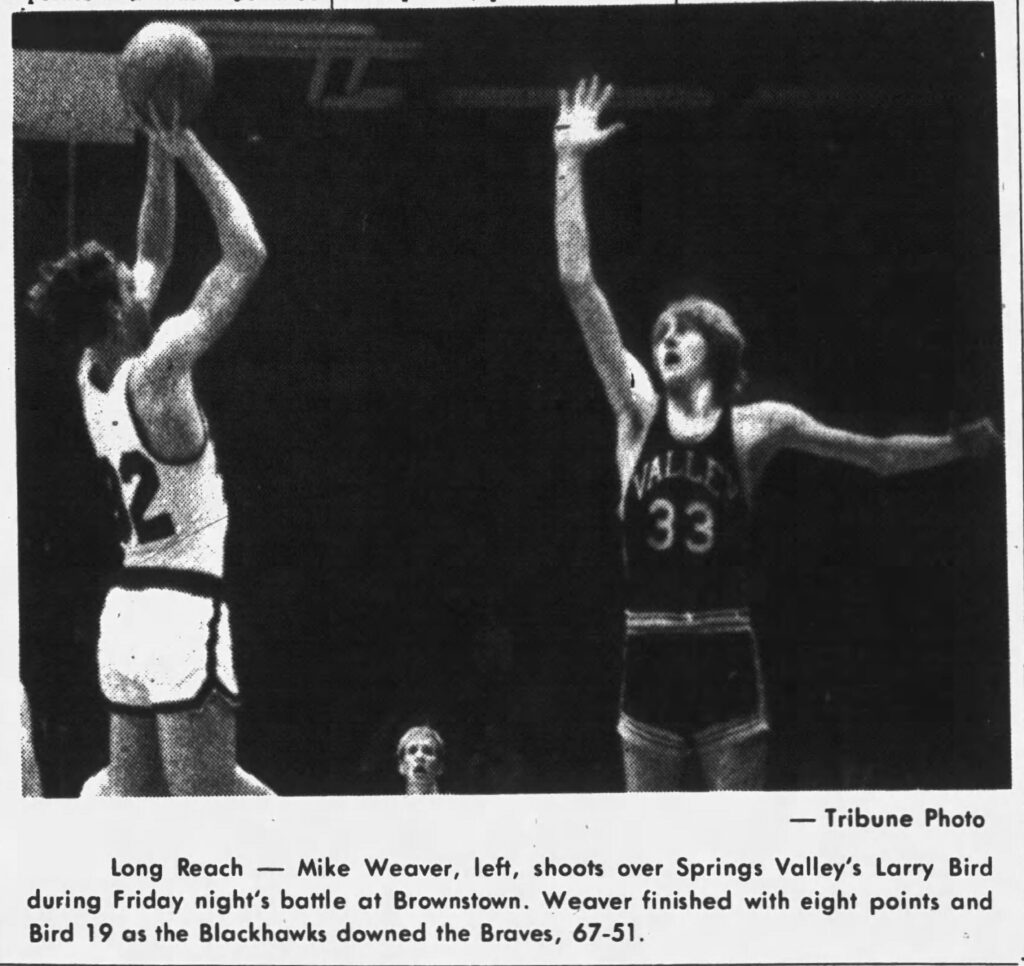

Valley roared to a lead, with not only Bird having his usual hot hand. Guard John Carnes was burning the nets up as well. Valley led by 20-11 after the first quarter, and 36-23 at half. The end of the third quarter had the Blackhawks up 48-40, rendering the Jasper fans silent. Then, ten seconds into the last quarter, Jasper made its move.

With 3:39 showing, big Mike Luegers made a tip-in that pulled the Wildcats within two points, and the fans went crazy. Bird came back and made two pressure packed free throws, but Luegers responded with another basket with 1:06 remaining. The teams traded baskets two more times. With seventeen seconds left, Jasper had a chance to tie the game, but failed to score on three attempts under the basket. Valley came away with a 60-58 victory.

Being nervous watching the close game, I had ended up spending most of the contest on the gym floor level, by an exit to the dressing rooms, an area where I could pace some as I watched the game. Immediately after the game, as the Springs Valley team walked back to their dressing room, I could hear the word Loogootee being repeated among them.

Bedford, with its poor record of just one game over .500 going in to the regional, and 9-11 after the regular season, was the biggest underdog among the 64 teams in regional play. Loogootee had beaten them by eighteen points in the regular season. With Indiana high school basketball games, however, every contest is a do-over deal. In the second morning game, as the Valley players watched in disbelief, Loogootee was on the losing end of the scoring totals at every stop, eventually losing by six points. The box scores revealed the dynamics of the unexpected upset. Butcher had his lowest scoring output of the season and Crane’s production was almost as poor. More surprisingly were the mistakes the Lions made, fifteen turnovers.

Whatever the disappointment the Valley players may have had about not getting another crack at Loogootee, they had to be pleased that they would be playing the weakest team in the tournament for the regional championship. If Valley won, the school would be going to the semi-state level for the first time since 1964. Just as important for Larry Bird, he might finally begin to receive the state recognition he deserved.

After Loogootee’s disappointing loss in the morning session, I was not sure if I wanted to go back to the final game that evening. But Lee Kavanagh convinced me to go, asking me, “You want to see Larry Bird play again don’t you?”

I certainly did.

Valley first moved ahead halfway through the first quarter when Larry scored under the basket and was fouled. He made the free throw to complete a nifty three-point play. I do not think anyone was sitting the rest of the game.

The Blackhawks were ahead at halftime 27-22 and had increased their lead to 44-38 at the end of three quarters. When they moved to an eight-point advantage with five and a half minutes in the game, sportswriter Jerry Birge imagined Valley fans were “making plans for the trip to Evansville,” where the semi state tournament would take place. But, Birge added, “the closing minutes produced one of the most dramatic come-from-behind victories in regional history.”

With little over a minute to go, Bedford cut the lead to one. After James Carnes missed a crucial free throw, Bedford finally took the lead and Valley had to foul to have a chance at winning. They were unable to score, and the Cutter fans went wide when the final score flashed up on the overhead scoreboard, 58-55.

In his autobiography, Larry laid some of the blame on one of his fellow players for missing crucial foul shots toward the end of the game, but Bird had an off-night too, being held to 15 points and hitting only 6 from 19 from the field. Also, in Indiana high school basketball, all’s fair. When Larry’s mother asked him why he had so many bruises on his legs after the game, he explained that the Bedford players had pinched him throughout the contest.

Now came my last brush with Larry Bird. As I had during the morning game, I was standing by an exit to the dressing rooms on the gym floor level. The gym area was roped off, but as I stood there, the Valley team came off the floor towards me, with Larry way ahead of the rest.

The disgust and anger on his face made me take two steps back. He flung the rope back over his head and walked right past me, sweat from the game completely flattening his usually moppy blond hair.

I knew better than to say even a single word.

_________________________________________________________

There was several dramas Larry Bird would be caught up in after he was through playing high school basketball. It began when Bird did not make the initial Indiana high school All-State basketball team of the fifteen best players in the state in late March, as chosen by the Associate Press. Jerry Birge at the Jasper Herald went ballistic. Under the headline, IT’S FOR THE BIRDS, Birge complained,

We read in disbelief today when the Associate Press announced its All-State team, six players on the first team and nine on the second team and didn’t include Larry Bird! The classy Blackhawk burst into the headlines in this past season with one of the finest individual seasons ever put together by a Hoosier basketballer. Bird had to be considered a legitimate candidate for “Mr. Basketball” honors.

Birge then went on to explain how the great injustice came about, pointing out that the sports writers in the northern part of the state and the Indy area had basically ignored him.

Larry Bird was a victim of the numbers. There is no daily newspaper in French Lick and West Baden to beat the drums for Bird, there is no radio or television station. We [the Herald] tried to do our part along these lines and distributed statistics and pictures of Bird to writers throughout the state, but their minds had already been made up.

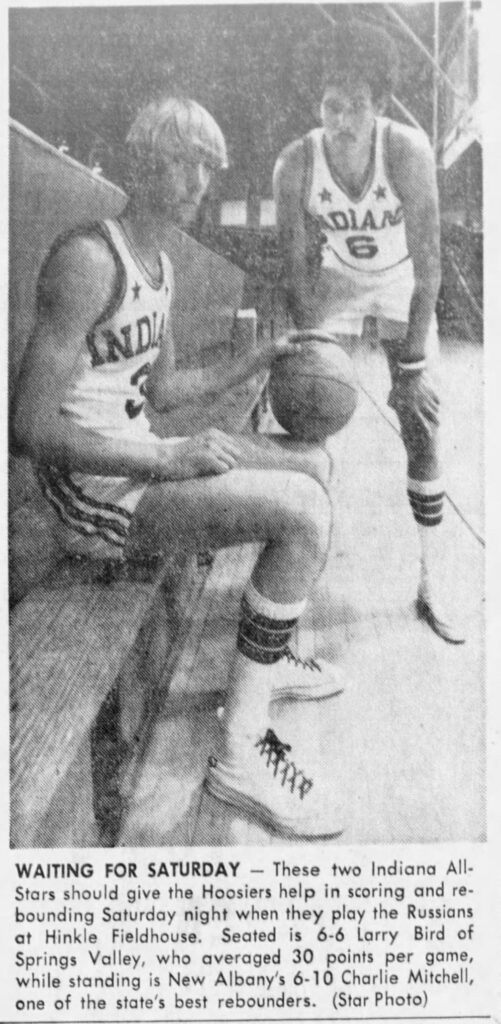

Birge’s work on behalf of Bird’s skills must have helped, as the UPI did vote him to play on the All-State team. Larry ended up being an essential part in Indiana’s victory over a traveling Russian team and against the Kentucky All-State team in their first of two contests. But that too ended in controversy in the second game between the two state teams when Larry got into an argument with the Indiana team coach.

There would more trouble in Bird’s journey to greatness.

Larry signed on at Indiana University to play for Bob Knight in April of 1974, after his high school season was over. He arrived on campus, but never made it to the first official practice. Homesickness, and the size of the new environment at Bloomington caused him to flee back to French Lick. It was also around this time that Larry’s father took his own life.

For a while Larry worked for the city, driving a truck, and for Hancock Construction out of Mitchell, Indiana. He continued to play AAU basketball, the games helping to keep his skill level in top shape. He apparently understood he still wanted to play basketball at a highly competitive level, having signed up to go to Northwood Institute, a local two-year school in town, but realized, “The competition wasn’t good enough there.” Then he was recruited by Indiana State University in Terre Haute.

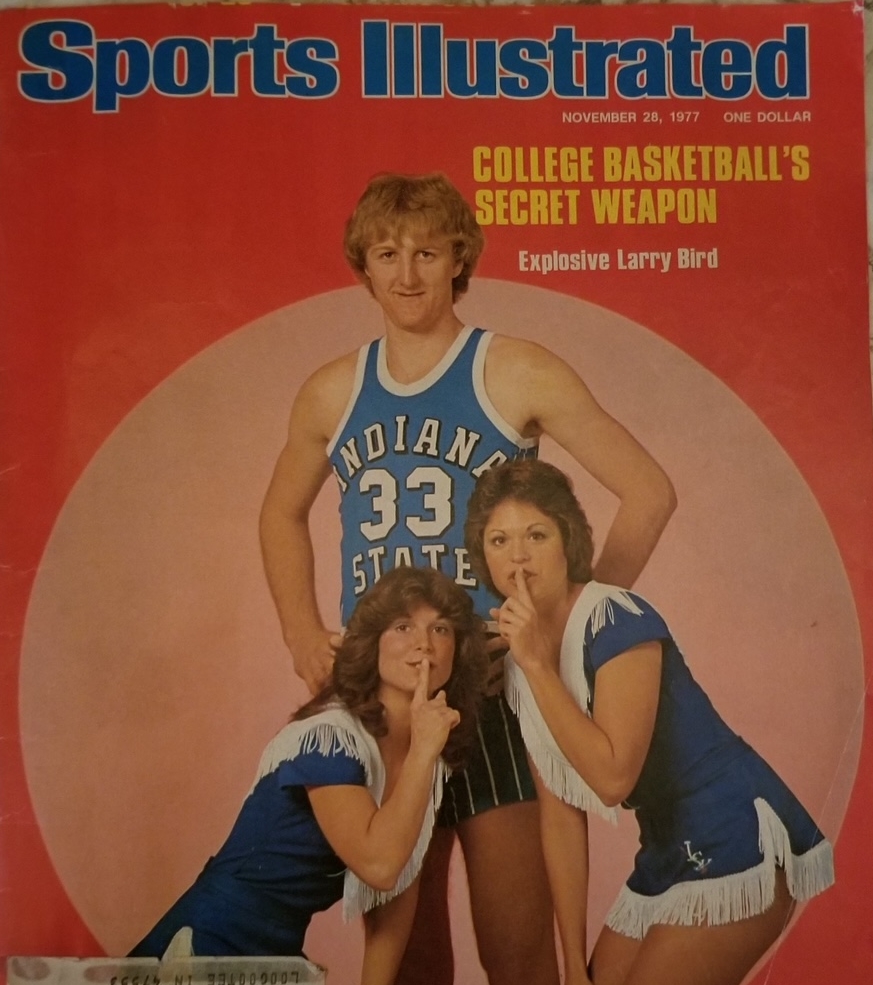

It was a perfect match of place and skill set, ISU being a smaller and more lower Midwest type of school than IU. Bird seemed to advance his skills there with every game.

Larry led ISU to an undefeated season his senior year in the 1978-1979 season and to the national runners-up spot, where ISU lost the championship game to Michigan State. Bird, however, was voted player of the year.

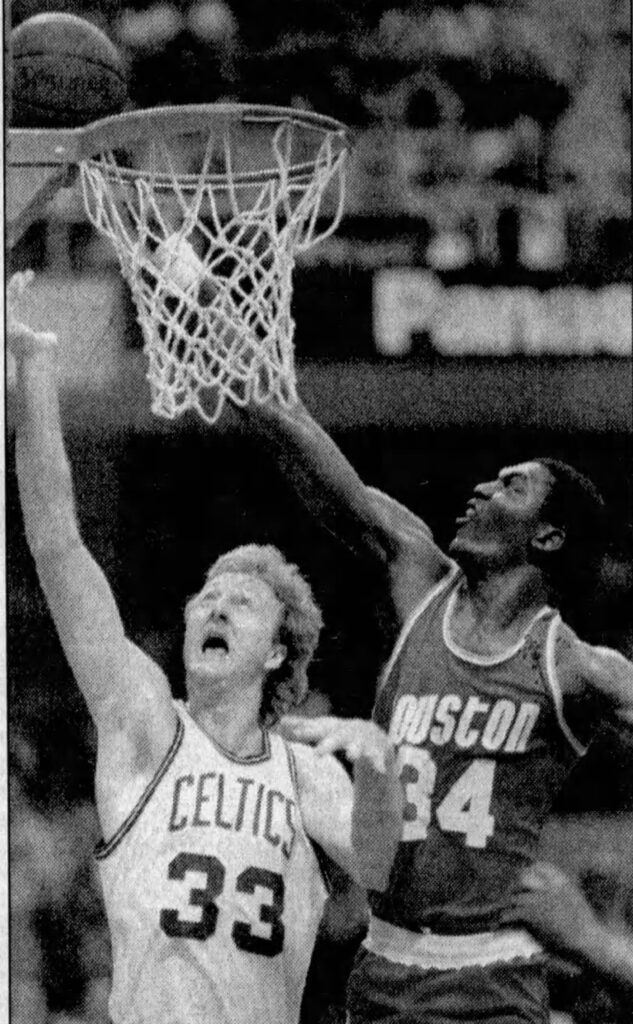

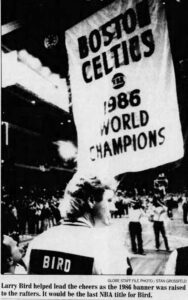

Larry was then drafted by the Boston Celtics, where he added two more inches to his height, topping out at 6-9. His play helped lead the Celtics to five NBA appearances and three NBA championships.

Many consider Larry Bird the best small-forward in NBA history. But as this narrative suggested, his journey to greatness, even after it became apparent how good he was going to be, was anything but easy. Perhaps the most interesting element of his life was how his skills seemed to have appeared out of nowhere.

I was fortunate to be there at the creation of the iconic Larry Bird, knew of him before his greatest, witnessing its first unfoldings that high school basketball season of 1973-1974. That year the Larry Bird of legend appeared, “as if by magic,” right before our very eyes. It was Jasper, Indiana, sportswriter Jerry Birge who helped us accept what we were seeing but could hardly believe, painting those first narratives that would grow into a national heroic tale. And if I had to characterize the essence of those narratives, it would be this: Larry Bird’s story, like every perfect looking jump shot he ever released, gives us ongoing hope that all things are indeed possible.