In the time of my early boyhood, my family and almost all our southern Illinois neighbors lived in farmhouses that were far from fancy, many of them one step away from dilapidation. While each house was distinctive in its own way, maybe with a painted front door or a roof line with dormers, most of them were tired looking affairs, their weather-beaten exteriors sagging in places with age. A few of these dwellings even seemed to list a bit, like a distressed ship at sea, or looked like they were slowly sinking into the ground.

It was the families living in these dwellings, however, that gave each house a subtle blush of life, as if the houses themselves were living things, in spite of their often rundown physical conditions. And just like living things, each house had a story.

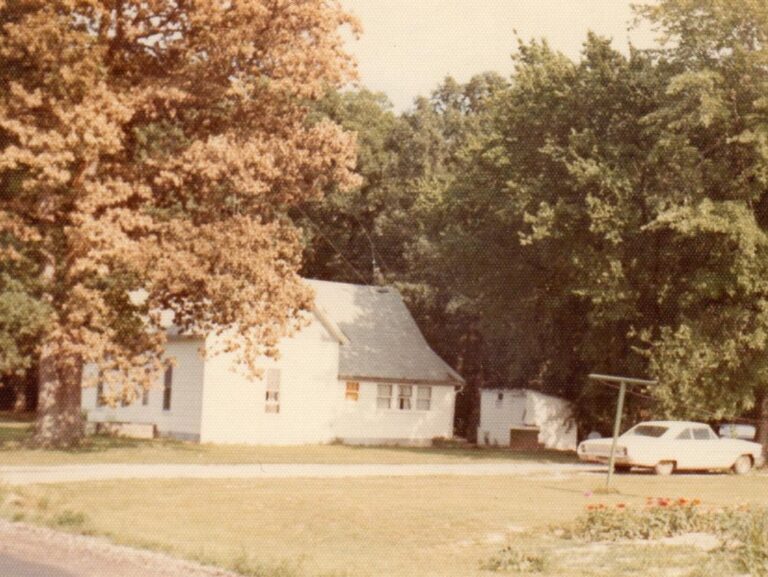

Our frame house was both plain and unusual, having once been wrestled onto a large crude sled and moved three miles distance to the location I remembered as a young boy. Built as a two room two story structure in the 1870s by a family named Greenwalt, it was dragged west in 1922 to suit its new owner, Arthur French. Tradition has it that the move was made during an exceptionally wet spring, the road so muddy it took the four-horse team two days to make the journey. I always imagined that while the horses strained and sometimes stumbled, pulling at the crude sled upon which the house perched, the driver recklessly urged them on, shouting and popping a whip above their heads.

Adding to the moving drama, the French family’s little daughter was so disturbed by the idea of her home literally being moved away that she hid in the structure on the early morning of the house’s departure, hoping she could stop the process. Instead, she was discovered and received a spanking for her efforts.

Once at the house’s final resting place, the structure was nestled down at the edge of a woods on the south side of the road. Shortly after this, a new addition was added, one that became the kitchen area.

This was the house of my earliest recollections, a structure with three main rooms—a kitchen across the south side, a living room in the northwest corner, and a bedroom in the northeast corner where we all slept. There was also a long narrow room running along the west side of the kitchen where a porch had been enclosed. The latter area was an unheated room smelling vaguely of dust and serving as a transition space between the comforts of the house and the capriciousness of the out-of-doors. Mom called it the mud room. Here, my father kept his cream separator, and Mother made us take off our muddy shoes when we came into the house from school or play.

Although the upstairs portion of the house had a small grimy four pane window at both the east and the west ends of the originally moved house, the unfinished attic could only be accessed from the inside, though a small, covered square shaped covered hole in the southeast corner of the kitchen ceiling. I often stared at the covering while I ate at the kitchen table, wondering if the boarded-up attic held some dark dusty mummified secret too terrible to be revealed.

Oddly, the back door on the south side of our house, the one that allowed entrance into the enclosed porch and then into our kitchen was the only door we used. The two front doors on the side facing the road were always locked and curtained on the inside. Since hardly anyone came to our house who wasn’t a relative or neighbor, they all knew to come to the back door, which was never locked. When a rare knock did come at one of the non-functioning doors, we knew a stranger was upon us.

In the early 1950s, there was an ongoing interaction between my family, the house, and the seasonal outdoor environment, sometimes a rhythmic synergy, sometimes a war. To better explain this ongoing drama, it is best to start with the most dramatic season.

In the winter, an invisible stream of cold air, like water, seeped through every window of our house and a fat “Warm Morning” coal stove was our only source of heat.

The stove sat in the middle of the living room like a granite rock, its glass door revealing entertaining tongues of orange and blue flames. In October, when the stove was first fired up, there was a vague lingering smell of dust burning. A pan of water on the heating stove and Mom’s cooking added some humidity to the otherwise dry air. Before it turned bitterly cold, the heating stove served as a cozy center of activities on into the early winter.

True winter brought the most drama, the temperature—both outside and inside the house—becoming an undeniable force in our lives. In the dead of winter, away from the stove and in our bedroom, we could sometimes see our breaths, little puffs of thin clouds that disappeared as fast as they popped up. Out would come huge thick quilts, as heavy as sheets of iron. Put yourself completely underneath them, and you’d grow hot enough to be uncomfortable. Poke your head out, and the cold would start there and work its way down the rest of your body.

One was left with no other alternative but to continually switch positions throughout the night.

When I was five, an indoor toilet was added to the house, along with a large room built on the east side of the kitchen. This latter addition become a living room, well-lighted by four sets of tall windows in the southeast and northeast corners. A new heating system was installed as well, a propane furnace where heat rose magically through a large rectangular floor register. No more nasty coal dust. No more building up and maintaining a fire.

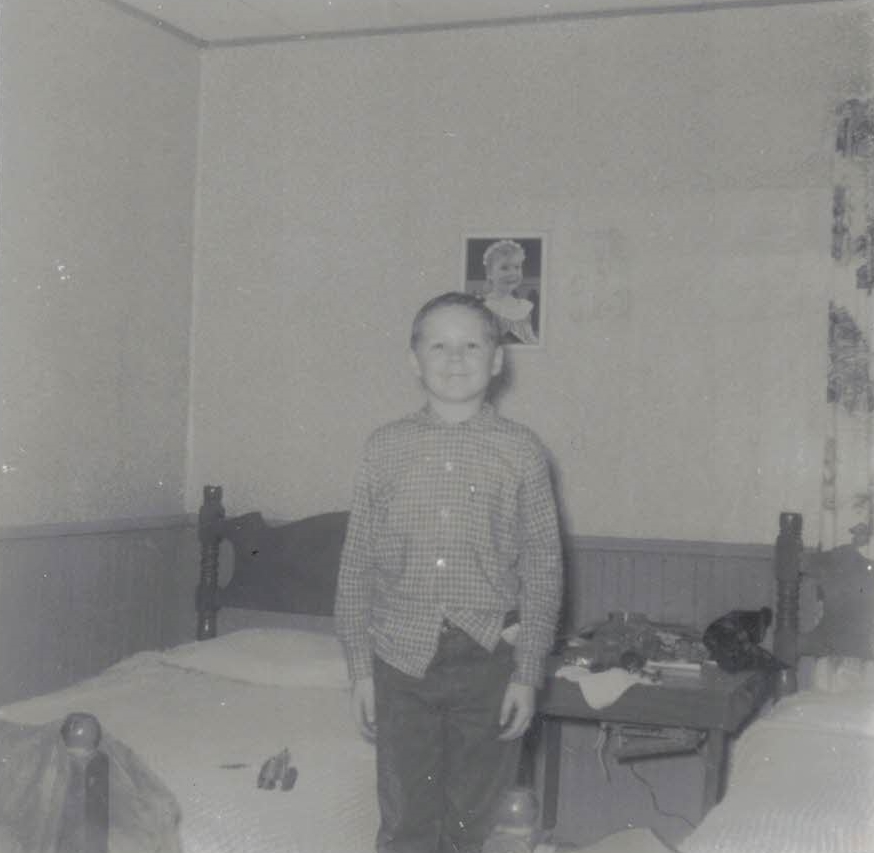

As a bonus, our parents and my siblings and I now had our own bedrooms. Ours was in what had been the former communal bedroom. My brother and I slept like kings in our own bunk beds. Marshall had the top bunk, I the lower. He liked for me to place my feet on the bottom of his mattress and bounce him, a game we played with great fervor until mom came into the room and told us to knock it off or until Dad came in with a belt. Karen slept in a crib across the room.

On the coldest winter nights, Marshall would sometimes climb down from his top bunk and crawl into my bed for warmth, placing his cold bare feet against my legs. Our poor little sister, Karen, had to fend for herself.

Because the road in front of our house ran straight and true for a half mile to the west and to the east, car lights coming from either direction at night would make eerie optical journeys across our bedroom ceiling and walls, stretched out at first before shrinking back together and disappearing completely as a car passed, a visual Doppler effect.

A car’s speed lent the only variation to the occurrence, and perhaps because it was night, and I was often half-awake at the time, these light shows were strangely disquieting.

It was difficult to feel what seemed like the living presence of our house in the daytime; there was simply too much going on and we siblings went outside whenever we could. But at night, in the deepening darkness, the house revealed itself with the soft creaking and sharp popping of oak beams expanding or contracting, along with the brief snatches of dissonant notes made by the wind slipping past the eves of the house with ghostly caresses.

Maybe too, our house simply wished to speak, to have company, to make its presence known.

In the early fall, there were purposeful scratching noises in the bedroom walls at night, the field mice sprucing up their winter quarters, and I imagined an elaborate city of mice somewhere inside the walls, with the tiny creatures all warm and snugly.

Spring and summer were the best times to be in the house. In the early spring, male whip-or-wills vied for mates in the deep woods just outside our east window, their haunting, incessant calls making their way into our dreams. In the early summer, we’d bring jars of fireflies into the bedroom and go to sleep, awash in slowly fading green flashes and a few small smears of green light on a bedpost where an escaping bug had escaped and been accidently squashed.

Once summer arrived in its fullness, the bedroom windows were lifted open to their rusted screens and a large fan was placed in our room’s window to pull the cooler night air into the rest of the house.

Nodding off to sleep, I imagined the house taking in cool breaths of air.

The noise of the fan was also a lullaby that brought restful sleep every night until the mid-summer. By then, the cicadas’ forceful choruses grew to become loud and primordial sounding, stirring up powerful feelings that I had yet to understand, leaving me elated and worn out at the same time when I woke up in the mornings.

As it turned out, there were no mummified bodies in the unfinished attic, just four large Mason jars with tiny bubble flaws in the blueish glass, the jars standing like soldiers in a neat row in a far dusty corner. Propped up nearby was a large wreath made of human hair, framed under a layer of filthy glass. These items were discovered when I was eleven, when our parents decided to add a room upstairs in the house for our growing family. It seems Marshall and I had reached ages that made our sharing a bedroom with our little sister problematic, although we were unaware of any problem at the time. Also, our little brother, Marty, had arrived. We three boys now shared a bedroom upstairs in the most modern area of our house.

A small portion of the upstairs attic was left closed off, however, with the four jars and the ghoulish hair hidden away and forgotten.

The change in bedroom location put my bed closer to the eves, so that I heard even the faintest notes of sound whenever the wind blew, the kind of haunting whispering sounds that were perfect for my adolescent broodings.

This bedroom arrangement would last until I left home for an out-of-state college in 1969, only coming back for a couple of summers before I married and established my own fledgling home in Indiana. The house seemed to age at an accelerated rate after my departure, looking smaller and more rundown each time I returned to visit my parents.

When our father died of an unexpected heart attack in our driveway in 1978, our mom remarried and went to live in another house, and Marshall and his young family moved into the aging home of our childhood.

Later, Marshall’s bunch moved out and Mother rented the house for a while, but the constant issues of upkeep drove her crazy. As the years ran by, the house seemed no longer able to hold up its end of the bargain. Floors began rotting out, walls sagged and grew out of alignment, and the plumbing constantly needed attending to. Finally, Marshall took action, letting us all know the house was going to be taken down.

On that day, a muddy bulldozer was brought in on a low semi-trailer. The dozer shook the air when Marshall fired its engine up, the prehistoric looking machine belching a dirty stream of diesel fumes as it gouged out a great hole of a grave just to the west of the house.

I was surprised how easily the house went down, sad that it had hardly put up a fight, as if it knew its time was over.

Marshall expertly pushed the debris into the hole before covering the dirt back over the split and broken pieces of what had once been our home. All this was done in less than a day. Mom cried, even after Marshall laughed and asked her, “Have you forgotten how ice froze around the bathtub and the damn toilet was always stopped up?”

A few days before the onslaught, I suddenly remembered the Mason jars that were still setting the closed off part of the attic. Feeling sick at heart about what was about to happen to our house, still managed to navigate around in that hot, dark place, probing with a weak beam from an old flashlight until I found them.

They stood, covered in the dust of ages, next to the macabre wreath of hair. Nudging away the framed hair with my foot, I grabbed up the bottles and carried away what would end up being the only physical remains I would ever have of the house of my boyhood.

My heart is a different matter. On those rare occasions when I chance to hear the wind whistle around an eve, or hear the faint call of a whip-or-will, our house still reminds me that it remains a part of my journey, a once safe and sure port in an often stormy world.