Of all my boyhood adventures in rural southern Illinois, nothing ever matched the experience of exploring, with my older brother, Marshall, abandoned farmhouses, places some of the local farmers swore were haunted. Like so many of the more interesting things in life, Marshall and I became aware of such places completely by accident.

It was in the mid-summer of 1958, when I was going on seven and Marshall on eight, that we heard our two dogs barking far to the south, their incessant howls echoing back to us in waves, letting us know they had something treed. Marshall sneaked in the house and grabbed an old single shot .22 rifle before Mom could catch him.

We hurried south, trotting down a slight hill by our barn and were soon out of breath.

Crossing a small field, we came to a narrow valley with a deep woods to the right and a brushy untended field on the left, the valley blocked by an old barbed wire fence half submerged in weeds. Up to this time, this point was our deepest exploration away from our house in this direction.

Without pause, we crawled under the lowest strand of the rusted fence and moved into some new and very unkempt landscape, hoping to find our dogs and their treed prey. The dogs, however, suddenly stopped barking. We heard them pushing and meandering through the undergrowth, headed our way.

They finally came up to greet us, panting heavily from exertion, their fur thick with pieces of twigs and seeds. Before we could pet them, they bounded off in the direction of the house, leaving Marshall and I more than a little peeved that our efforts to find a treed animal had been in vain. As I turned to walk back, however, my always adventurous brother said, “Might as well do some exploring.”

We continued to walk south, deeper into an area we were completely unfamiliar with. Thirty minutes later we came out of heavy woods and stepped onto a narrow dirt lane that was slightly sunk into the ground, a sign it had once been well traveled. Just a few steps to the right, another dirt lane, so narrow that it was little more of a path, curved into a grove of ragged trees.

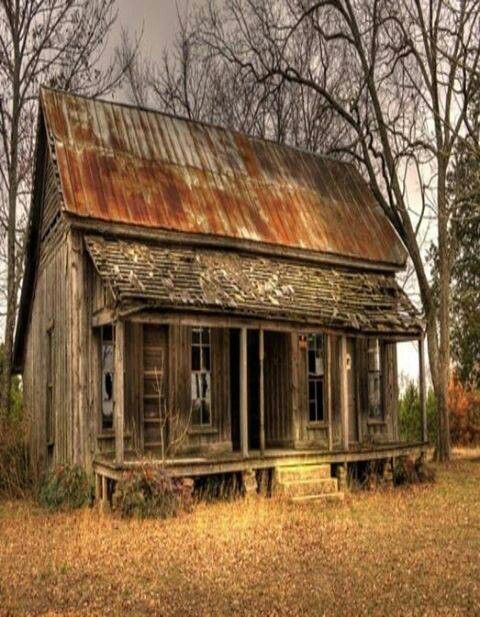

As a sudden breeze shifted tree limbs back and forth, portions of a second story of an old paint-peeled house peeked out at us. We were stunned by the site of the broken down house, its existence there in the middle of nowhere.

Marshall gripped the old rifle at ready, and we approached the house cautiously and without talking. Several steps later brought the entire house into view. The windows were mostly broken out, and a portion of the back roof was caved in.

“It looks like it could fall in on us,” Marshall whispered.

Something about the house, however, beckoned to me.

“Do we go in?” I asked.

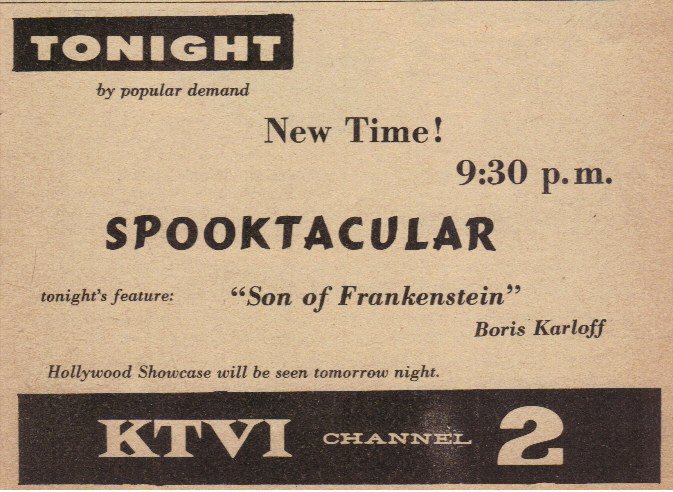

It is likely our decision to return home that day without going inside the house was shaped by a recent event. Marshall and I had started spending occasional Saturday nights with our grandparents on the Mills side, who let us stay up late to watch television after they had gone to bed. We always watched a scary horror movie on a late night show called Spooktacular.

The one we had watched that Saturday, a few days before we discovered the abandoned farmhouse, had an opening scene where a shadowy figure lurched around in the dark, looking through several lighted windows of an old looking farmhouse at night, a building that looked much like the one we had stumbled upon. The fear factor was increased in the black and white movie by the sound of a howling wind in the background.

Whoever or whatever was doing the spying in the movie found a darkened window and proceeded to open it. The movie then cut to an inside room where a family sat around a kitchen table quietly talking, the howling wind muting most of the conversation.

Suddenly, a doll’s head comes rolling out of an unlighted side room and goes under the table. You can go ahead and image the rest.

Fast forward a few days. After taking a long look at our old house discovery, Marshall whispered to me, “It looks just like the one in the movie.”

That was that.

Shortly after our visit to the abandoned house, some of the local farmers told us the place was haunted, probably a ploy to keep our noses out of there, although one of the men seemed genuinely scared. In the end, there was one essential thing that hindered us from going back—in almost all the horror movies we had watched, there always seemed to be a group of stupid kids going into an old, abandoned house, with the ending always an unhappy one, to say the least.

******************************

Three years later, we finally walked back to the old house. This was on a Sunday afternoon, and our trek involved a dare from the preacher’s son who was visiting with us before we all went back to Sunday night church. He was a few years older and desperately wanted us to take him to the abandoned house he heard us often taking about.

“I bet it’s haunted,” he said.

His tone was a dare.

Marshall and I were older and braver, no longer buying into the haunted house thing, so we said yes. “Besides,” Marshall whispered to me, “there would be three of us.”

It was mid-November and none of us were driving yet, so after lunch we walked straight south for a mile or so, the Indian summer sky as blue as crystal.

We soon shed our jackets after the first couple of minutes of walking through a dry dusty bean field that had recently been harvested, the dust we kicked up tickling our noses. One of our dogs, Rex, our collie, darted around us as we walked, checking out holes in the ground and clumps of brush and grass where a rabbit might be hiding.

Marshall and I had not been to the house since the first time we found it. The forlorn structure—what was left of it, anyway—rested in a small grove of trees, mostly maples. Although loud and boisterous when we had started walking, we grew silent as we made a final approach to the sagging building, its paint long peeled away, leaving the wood the texture of gray bone. I only hoped the others didn’t hear my heart beating harder with each step I took.

At first, the three of us circled the house, just as Marshall and I had before. This time, however, I paid more attention to the details. All the windowpanes were gone now, and a thick woody vine coiled through one of the open windows like a giant sleeping snake. To add to the gloom, no songbirds called, as they had in the summer of our previous visit.

Now, only a few hardy crickets chirped pointlessly at our feet, hiding deep down in the coarse thickness of the taller weeds. Even the trees had lost most of their fall glory; only a few blood red leaves here and there trembled in the breeze. It was then I realized our normally hyper-curious collie was nowhere to be seen, having apparently gone home.

It crossed my mind that he had sensed something disturbing. And then I remembered that no dogs ever went into haunted houses with their masters in the horror movies I still relished.

We came up to the front porch, pushing away the drooping tree branches that guarded the house like sentries. Oddly, Marshall and the preacher’s boy, both older than me, hesitated, so I stepped up onto the crumbling porch and disappeared inside. They followed—reluctantly I thought.

We entered another world, the outside sunshine and blue sky made mute inside by the subtle bleak atmosphere, a condition created by a mixture of unique and poignant odors along with the poor lighting. The dimness made it seem we were walking under water.

The house had been in a decaying state for many years, as if it were slowly being absorbed back into the earth. Mold was the strongest smell, competing against a lesser animal odor, a kind of wet dog scent. The wooden floors had rotted away in many spots, and wild animals, probably groundhogs or raccoons, had dug dens in the corners of most of the ground-floor rooms.

I moved from room to room, always ahead of the others, checking out the bits of scattered trash—pieces of rotting cloth, old broken crockery, and wads of yellowed paper—laying at my feet. Curiosity, like an invisible hand, pushed me forward.

The house felt alive, as if it longed to tell me something. I just had to see what might be in the next room.

I finally stopped to wait for Marshall and the preacher’s boy when I came to an extremely narrow stairway off the kitchen that led upward. We climbed single file up the tight steep stairs, me first, a climb made more difficult by the short width of the steps.

“I suppose folks must have had smaller feet back then,” I said.

The preacher’s boy laughed behind me and said, “Bet this is what climbing up the gallows feels like.”

We found all the glass panes and frames busted out of the upstairs windows, the ample openings on either end of the upstairs room letting in a pleasant breeze and plenty of sunlight and providing an inviting vista.

We sat for a long time with our legs crossed in front of the south window, looking out from the second story onto a panoramic view of fields and woods and talking about the all the things adolescent males of that day pondered, until the changing angle of the sun’s light gave warning that we needed to get back and prepare to attend Sunday night church.

That evening, all during church, I still felt an exhilaration from going inside the abandoned house. Then, oddly, the next day brought a hangover of shame, a feeling I had seen something forbidden and was doomed for it. But there was yet another feeling that cropped up. Like a future drunk having his first drink, I had walked away from that old house knowing I was going to do that again.

******************************

By the next spring, Marshall and I knew the whereabouts of every deserted farmhouse within a ten-mile radius of our home, these remote places drawing us like magnets, filling our day with adventure. Many years later, I would read how the great American agriculturalist, Solon Robinson, once observed that the impractical and sullen upland southerners who came to settle in great numbers in the area of my boyhood typically built their homes far off the main roads, down narrow, lonely country lanes, seeking the solitary environment best suited for their melancholy moodiness. New Englander settlers, on the other hand, were a more sensible lot, or so thought Robinson. Once they arrived on the Midwest frontier, they butted their homes right up against a main road where it was easier to carry on commerce, interact with others, and make money.

I am uncertain how Solon Robinson, himself a native of New England, came to these convictions, but perhaps his notion does help explain the location of all the old abandoned farmhouses Marshall and I came to discover. These houses most often lay nestled back in fields and woods, far out of sight, and could be accessed only by traveling down barely discernible, overgrown roads.

One of our earliest experiences exploring an abandoned home place was particularly memorable. In the middle of an especially hot and dry summer, we informed our mother we were riding our bikes over to see our grandparents. Instead, we changed course once we had gotten out of sight of our house. Our real destination was a rough dirt road that carved through a local farmer’s field like a dusty scar, and the deserted house we knew waited at the lane’s end.

We pedaled like little demons up a hill, past our simple clapboard church, Wells Chapel, and then down the hill, gaining speed, until we came to a dirt lane to our right. We bounded off the main road, racing. Marshall, standing up on his pedals, pumping hard and moving side to side, sprinted ahead of me on his smooth-riding roadster, his thin bike tires kicking up little puffs of dust. He surged around a sharp curve, disappearing. I struggled to keep up, pedaling my clunky bike with its fat tires.

I found Marshall’s Schwinn leaning up against a small barn that stood perhaps fifty yards from a weather-beaten house. Half the barn’s roof had caved in, and to one side a rusted tractor -pulled combine, its tube-like auger angling from the side like a neck of some prehistoric creature listing half-submerged in the tall weeds and tree saplings.

The barn was empty and of little interest.

The two-story wood framed house was another matter—windowpanes missing in several places, a scrap of ragged curtain, perhaps moved by a slight breeze, stirring in one of the front windows, like a hand waving.

What pieces of window panes were left caught the sun off-and-on as I slowly approached the house, causing the glass to wink.

Marshall, sweaty and with a sly grin on his face, was standing a bit off from the farmhouse, awaiting my arrival. He half goosed, half pushed me toward the dilapidated house.

Morning glories twined around a porch post, the open petals a beautiful but in congruent cornflower blue among all the dull brown and gray colors of dilapidation. I pressed the heel of my hand against the front door, which turned out to be half rotten, my hand pressing deep into the decayed wood.

No matter how much older and wiser we had grown, like always, there was a moment of sickly terror when we stepped into the house. I went first, moving only a couple of steps forward before stopping, waiting to make sure Marshall was following.

Neither of us spoke. Typical pungent odors of mold, dust, and animals denning hung in the closed air. This silence carried an emotional charge that caught even my brother’s short attention span. Who knew what waited upstairs, behind a closed door. Visions of all those scary movies seen at our grandparents flooded our brains.

The anxiety waned when a mouse scurried inside a wall. A breeze, not unwelcome in the heat, gently rattled one of the broken windows.

We moved deeper into the house, curious again, me still in the lead.

Squirrels had been in the house. A variety of gnarled oak and hickory nut parts lay scattered all over the floor, crunching beneath our tennis shoes. Articles of clothing, lying strewn about, had been mostly chewed up by the mice. What was left of the dusty, rotten fabric fell apart in our hands.

There were a few pieces of broken furniture lolling about—in one room a kitchen table was turned upside down, missing a leg, with two broken chairs keeping it company. In another room a battered writing desk with elegant, curved legs, missing all its little drawers, sat like a sphinx. The desk suggested the owner had possessed some education, perhaps had written some interesting letters, or kept a revealing diary that we might soon find.

Upstairs lay the only written material left in the house: a tattered detective magazine, hidden in the back of a closet. The issue still had its slick cover—a photo of an attractive woman in a disheveled, soiled slip, her mouth twisted in a mute scream, accosted by a rough-looking man who badly needed a shave. Other risqué sketches awaited inside the volume.

Marshall and I took long turns looking through the magazine.

The oppressive heat, along with growing hunger, finally took the edge off the excitement of that first long exploration. We hardly talked as we rode our bikes homeward, and we never told our parents where we had been. We were both now clearly possessed by what we came to call “spook house hunting.”

******************************

That year we spent many hours searching out and exploring abandoned houses in our region, often making a day of it. We’d sneak out two flashlights from Dad’s closet in the morning after he left for work, and later, carefully return them. We’d carry sandwiches in brown paper bags, along with washed-out peanut butter jars filled with Kool-Aid, the lids twisted shut extra tight.

We discovered and explored a variety of abandoned houses, from very bare, stripped-down buildings used by farmers to store grain or hay, to houses halfway intact, with a variety of once personal and meaningful items inside. Some of these objects were especially interesting, morality tales in a way, as they were once noble, functional items now made sad and forlorn in their demotion to un-understood junk.

Written items in our spook houses suggested a once-flourishing rural world now forgotten. One note was stuck away in a closet, penned in the loopy scrawl of a young girl.

Deer Cousin,

You were asking about how we were—George sick,

Ma grumpy, dog gone.

Your Cousin,

Kate.

Even Marshall understood there was something animated and interesting in these written items, once retrieving a farmer’s tattered pocket notebook containing the strange notation,

“Wilson’s boar put to sow today. Will give birth Nov. next.”

He placed the booklet in his hip pocket, surprising me with his sudden interest. For some reason, I never removed even one item from any of these deserted houses, although there was one I wish I had.

I discovered the interesting item the one time in my boyhood that I went into an abandoned house without my older brother. During the entire time I rummaged through the house, I felt uncomfortable. Up in the attic, a tight dark place so hot and close I could hardly get my breath, I found a ragged brown scrapbook in a pile of moldy smelling books and took it downstairs to explore its pages.

Downstairs, I saw one corner of the scrapbook was badly burned and I was disappointed, thinking the material inside would be mostly destroyed. That was not the case. In front, and halfway through, the book was full of sports ribbons, newspaper clippings, and canceled tickets from high school sporting events in the 1950s. Whoever compiled the book had done a great job, the young man’s sport successes from that that day revealing themselves as if had only been yesterday.

I was ready to keep some of the ribbons until I got to the second part of the scrapbook, a section with four personal letters. The one-sided correspondence told the story of the young man’s short-lived love with a high school classmate, an affair that ended with her telling him she just wanted to be a friend. I put the scrapbook, fully intact, back where I had found it.

Marshall and my last journey into an abandoned house was as dramatic as any we would experience. We discovered a house where everything was pretty much left intact, as if the people who once called the place home had just stepped out to go to the store or visit a neighbor. On first checking, we found the doors and windows were completely undamaged and shut down tight.

We peered through every one of the dusty, grimy windows, looking for any sign of recent human occupation, but the wild, unkempt yard, filled with high weeds and volunteer trees more than a few years past being saplings, and the great depth of dust we could see inside told a story of undeniable abandonment. We did not know at the time that the visit represented the high point of our exploration of abandoned houses.

On a second check, Marshall found that one window’s casement had rotted. After some struggle, he pried the window open and we crawled inside, shaking with excitement.

Perhaps it was the open letter on a table, yellowed and curled that changed our mood, made us wonder what possibly could have happened to make a family leave a house in this condition, completely intact. Our watching normally forbidden movies years ago on television at our grandparents did not help, as the movie scenarios suggested several awful possibilities. Had the former occupants of the abandoned house all been taken away by aliens, or murdered, or seen something so horrible they fled the house and never came back? Worse still, was one of the family members, perhaps grown crazy, sleeping upstairs?

For once I was the one who wanted to get out of there, having the sudden vague and unreasonable fear the owners would walk through the door at any minute and demand to know what in the blazes we were doing in their house.

Our interests in going into abandoned houses seemed to disappear after that visit, although I’m not sure why. Perhaps the gloominess of these places finally overpowered the excitement we often felt. Many years later, reading a book by a sociologist on so-called hauntings, I came across the idea that once occupied places often possessed an ongoing aura, a “seething presence,” left over from all the dramatic things that occurred there, a presence that could be felt under the right conditions. There was also the fact that I was becoming more engaged in sports and in schoolwork, and, in the summer months, working in the hay fields. Marshall, meanwhile, spent his time working at different farms, driving large tractors and trucks, and fixing things.

I, however, was to have one more haunted house adventure.

******************************

Somewhere in my junior year of high school, I fell in love with a girl a year ahead of me in Marshall’s class. The event blindsided me. One day I was normal and the next day I was completely smitten. Of course, my interest had been building up without my realizing. Most of it was probably in my mind, making the experience even more painful. I was too scared to tell her how I felt—after all, she might laugh in my face, or, scarier still, say she was interested.

We would sit beside each other in the gym bleachers in the mornings before school started, just talking. I finally worked up the courage to ask her if she would give me a picture of herself and was elated when she did.

“It’s not very good. I look so serious,” she told me when she brought it the next day.

I thought it was wonderful.

One morning while sitting on the gym bleachers I told her how I liked going into old, abandoned farmhouses when I was younger, and all the interesting things I’d found. She seemed intrigued. That weekend, a Saturday afternoon, she took me to such a broken-down place near her house. I was ecstatic.

It was a bright sunny day in October and the fall foliage was spectacular. The house set in a small grove of gnarled maple trees whose leaves were so deep red and glowing, they seemed to be on fire. Surprisingly, she did not go in, telling me she feared ghosts. I laughed and strolled in, but I was disappointed that she didn’t follow. I was hoping the spooky atmosphere would make her lean against me as we explored, maybe hold my hand.

She must have been on to something. I felt uneasy the moment I started walking through the junk-strewn rooms alone, the walls covered with moldy hanging strips of yellowed wallpaper. I sensed the presence of something lurking in the ransacked house, a portent, perhaps, of sad things to come.