Like other young boys growing up in the 1950s in the Horse Creek region of rural southern Illinois, I was keenly attuned to the seasons.

At that time I would have said summers were best—the twisting off of a big ripe tomato from a woody vine and eating it on the spot. Autumns, while breathtaking with color, were melancholy, the final waning of the love affair that was summer.

Winters were my least favorite time, my family being crammed together in the confines of our three-room farmhouse, causing an increase of quarrels among all parties, especially among us siblings.

Then there was spring, an imperfect season to be sure, one about which I still carry mixed feelings, the cruelest month to quote one poet.

I recall one boyhood April day in particular, the memory capturing my naive and romantic notion of the spring season. Balmy south winds carried the pungent fragrance of wild crab apple blossoms to our door and through our open windows. Somewhere farther south, a new generation of tiny peep frogs croaked out a primal chant, an incessant driving song older than humankind. Their calls, like the smell of the flowering crab apple trees, drifted on the wind, so that the sound came and went with the capricious breeze. These things—the smells, the sounds, the radiant sunlight—were like Greek sirens.

I threw on my most ragged pair of jeans and a torn sweatshirt, pulled on a pair of gum boots, and headed south, slopping over spring-rain-sodden ground, coming to stand on a slight ridge that overlooked a narrow marshy valley that my Pierce ancestors had once farmed. A red-tailed hawk, pinned against the blue sky, gave out a sharp, shrill call. Startled mice and shrews shuddered, the unlucky ones losing their nerve, scrambling through the lush green growth of new spring grass, easy pickings for the hawk.

I laid on the ridge for hours, my hands clasped behind my head, watching the hawk soar above me on invisible waves of warm rising air. I basked in the spring sun like a tourist on a beach, listening to the frog chorus whose pitch and notes never wavered. When I walked back home in the dusk, the calls of whip-or-wills echoing through the woods turned to daggers of longing for things I did not yet understand.

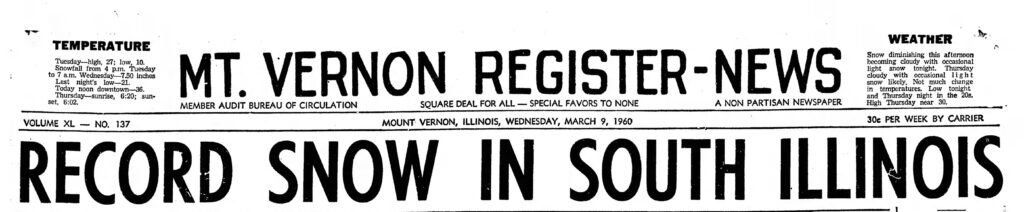

Two days later the afterglow of that memorable experience was shattered. The weather turned so cold, you could see spits of snow spinning around in the north wind, the crab apple blossoms shriveled, and the peep frogs went back down into the mud to wait for another warm day. It was as if spring’s magical promise had been broken.

The most dramatic aspect of the springs of my early boyhood, however, were not the extreme back-and-forth temperature changes, but rather involved a more fearsome force of nature.

Warm energized winds from the southwest would occasionally bring fat, unfolding cumulus clouds rushing across the sky, clouds that carried amazing amounts of moisture up from the Gulf of Mexico. When this warm weather system crashed into a gigantic mass of cold dry southward-moving air hurling down from Canada, the confrontation often birthed tornadoes of all sizes. It was when this process took place over southern Illinois that the curtains would rise on a four act play at our house.

First came a phone call from our Grandma Mills, who, when a warm front came rolling in, a situation she claimed brought the smell of electric energy with it, listened obsessively to the radio throughout the day. She would spin the rotary dial of her phone like a maniac the moment the weather man said to be on alert for possible storms.

Once that phone call came, my immediate family also began to linger around our own static-filled radio. When weather warnings began breaking into radio programming like World War II sirens, telling of all the possible damage to expect if a tornado did form, Dad got primed for action, putting on his shoes and gathering his tobacco pouch and pipe. Meanwhile, the entire family now circled as close to the radio as possible, every head bowed down and leaning towards the glowing dial, as if in prayer.

Any breaking weather bulletins announcing an actual tornado on the ground in Jefferson County would bring the family to another stage of the drama, Dad hollering, “Get in the car!”

We ran from the house as if our lives depended on it.

Poor Karen, our little sister, would desperately grab one of her dolls, crying loudly because she had to leave the rest. Marshall and I cared less. To hell with the dolls, a tornado was a living monster.

A hair-raising dash, often through heavy rain got us into our car. Once on the road, we spied out the windows for any signs of funnel clouds, like wet, terrified soldiers looking for enemy planes.

Three miles down the road, planted at the top of a short flat hill, like a Grant Wood painting, stood my father’s parents’ house. Although not much bigger than our house, and certainly no fancier, it did have one very important thing our place did not—a basement. Once we arrived there, we’d pile out of the car and move quickly for the front door.

Inside waited our Grandma Mills, patting each of our heads as we moved by, directing us toward the basement stairs.

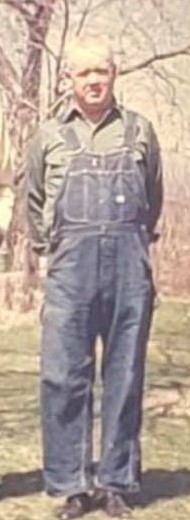

On the couch, most often reading a newspaper, was our grandfather, lounging as cool as a cucumber, eyeing us with some contempt as we filed past, his disdain springing from the fact that just such arrivals in the past had, so far, played out without a single tornado in our immediate area. The fact that Grandpa was my siblings’ and my hero made the situation even more shameful.

It did not help matters that we were often sopping wet, moving too fast to say hello, trying to get to the stairway that led to the dank basement.

During all those times that we rushed to my grandparents’ house to find shelter in their basement, my grandfather never once came down to join us, staying upstairs instead, where I supposed he watched the weather with the same defiance in his eyes as when he’d watched us scrambling to his basement.

___________________________________________

One spring day in 1957, when I was five, the danger of a tornado was real. A serious sounding voice on the radio, like the voice of doom, announced there was a large tornado on the ground and moving in a direction that likely put our house directly in harm’s way. We had the drill down, of course, and when we got to our grandparents’, we ran to the basement without being told. This time, each of us was assigned a place to huddle down under a blanket and wait for the storm to pass. Surprisingly, our grandfather stayed upstairs as usual.

There have been few things eerier in my life than seeing my family members lying completely still and motionless under my grandma’s heavy quilts, as if they’d been frozen by the stare of Medusa. We had not been hunkered down very long, however, before I quietly left my place of safety and stole upstairs to check on Grandpa.

Outside the windows, the light possessed an otherworldly green tint, the atmosphere still and holding in an unearthly calmness.

I checked every room, but Grandpa was not in the house. Fighting every instinct to run back down the stairs, I walked outside.

Grandpa Mills was across the road, standing at the peak of the hill, looking down at a wide and long view of mostly fields, the scene broken up by a few small woods and ragged fence rows. He turned and motioned me to stand at his side.

The tornado was perhaps a mile away, moving from southwest to northeast and not in our direction.

The funnel’s dual motions, its moving forward at great speed while swirling like a top, was disorienting. Unidentifiable objects of various sizes moved up to the top of the vortex, then floated away from the tornado. Or dropped altogether. Like stones.

Grandpa suddenly pulled me to his side and wordlessly pointed up into the sky. Something haphazardly floated our way, high up in the air and small at first, but growing larger as it spiraled down—falling, rising, falling—as it drew nearer.

I could not move, mesmerized, sensing the strange object was going to come exactly to where my grandfather and I stood. And it did.

With one last gentle upswing, like a giant feather, it softly settled down a dozen yards or so from our feet, an odd-shaped piece of rusted tin from a barn or shed, twisted and folded, looking for all the world like an angel’s broken wings.